The 2017 tax law, known as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), enacted large corporate tax rate cuts, reducing U.S. corporate tax revenues to about 1 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). Because peer nations typically raise about 3 percent of GDP from their corporate tax, and U.S. corporate profits have been at historically high levels, one might question whether the TCJA’s cuts to the U.S. corporate tax rate were too large.1

While increasing the statutory corporate tax rate would generate substantial corporate tax revenues, reforms to the United States’ international corporate tax regime could also raise revenue, while simultaneously reducing profit shifting and offshoring incentives.2 This issue brief discusses several proposals for international corporate tax reform, providing a range of estimates for the amount of revenue that reforms would bring the United States.

Background on the U.S. corporate tax

Prior to the passage of TCJA, the U.S. corporate tax rate was 35 percent, and U.S. multinational companies (MNCs) were taxed on their worldwide income at the same rate, with two major caveats. First, corporations were allowed foreign tax credits for taxes paid abroad in order to avoid double-taxation on foreign income. Second, tax was not due on foreign profits until repatriation. In the early years of this system, U.S. companies had sufficient foreign tax credits to offset the amount of U.S. tax due on foreign income, allowing them to repatriate without owing much U.S. tax on this income. But as time passed, and foreign countries lowered their tax rates below the U.S. rate, fewer companies had sufficient foreign tax credits to avoid tax at home. So, they left income offshore, where it could grow tax-free. To finance investments at home, or for other uses, companies were free to borrow. This effectively gave them tax-free access to their earnings offshore, since interest costs were deductible at home, but profits offshore earned taxable interest. Companies therefore postponed repatriation in the hope of a tax holiday, such as that enacted as part of the American Jobs Creation Act of 2004, or a lighter tax upon transition to a territorial system, which exempts foreign income, as occurred with the TCJA.

There was widespread taxpayer dissatisfaction with the prior system, in part due to the inconvenience of the tax upon repatriation. Activist shareholders and companies organized substantial lobbying with the goal of making the U.S. international tax system more “competitive.” They often pointed to the high U.S. statutory rate relative to peer nations, as well as America’s purportedly “worldwide” system, as reasons to align the U.S. system with those of its peers, despite the fact that the U.S. government raised little revenue from taxing foreign income.3 These comparisons neglected the fact that, prior to the TCJA, the U.S. government raised about 50 percent less, as a share of GDP, from its corporate tax than did peer nations, despite having high—and rising—corporate profits, in part due to the aggressive profit shifting of U.S. MNCs.4

International tax provisions in the TCJA

Enter the TCJA, which combined a massive corporate tax rate cut—from 35 percent to 21 percent—with a purportedly “territorial” system of taxation that exempted foreign income from taxation.5 Because of the TCJA, corporate tax revenues have declined sharply, further increasing the discrepancy between U.S. corporate tax revenues and those of peer nations.

Compared with the prior system, the new territorial system actually collects more tax on the foreign income of the most tax-aggressive MNCs, since it taxes some foreign income as it is earned rather than when it is repatriated. In particular, there is a global minimum tax, known as the global intangible low-taxed income (GILTI) tax, that applies when the global foreign tax burden for the multinational group is sufficiently low; the minimum tax applies at an effective rate of between 10.5 percent and 13.125 percent. But the first 10 percent return on physical assets located in foreign countries is exempt from the minimum tax, providing an incentive to offshore physical assets in order to reduce the bite of the minimum tax. In addition, because the GILTI tax is based on companies’ global tax burdens, it has the perverse feature of encouraging all foreign income relative to U.S. income. Haven income—income reported in jurisdictions where corporations pay little or no tax—is of course taxed at a lower rate than U.S. income, but even income in higher-tax countries comes with tax benefits. For example, German income generates foreign tax credits that reduce the tax burden associated with the minimum tax on haven income, whereas U.S. income has no such beneficial consequence.6

In addition, the TCJA includes a tax preference, known as the foreign-derived intangible income (FDII) deduction, for U.S. export income above a certain return on assets. This provision also acts as an offshoring incentive, since—all else being equal—reducing assets in the United States increases the benefit of this export subsidy. Most experts conclude that this provision is likely to be ineffective in altering companies’ intellectual property location decisions, as tax treatment abroad is generally more favorable. Also, the provision may not be consistent with the United States’ World Trade Organization (WTO) obligations and will likely be challenged by trading partners.7

Options for international tax reform moving forward

First, it would make sense to repeal the FDII. This costly export tax preference is unlikely to be effective, may be incompatible with WTO rules, and is perhaps even more costly than the congressional Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) originally estimated.8 Using JCT estimates, repeal would generate increased U.S. tax revenue of between $127 billion if one assumes a 21 percent corporate tax rate and $212 billion if one assumes a 35 percent corporate tax rate.9

Second, the global minimum tax could be replaced with either a higher global minimum tax at the regular domestic U.S. rate or a per-country minimum tax at a rate lower than the domestic rate. Either option would dramatically lower profit shifting incentives relative to current law. In addition, the present exemption from tax for the first 10 percent return on assets could be eliminated, in order to remove offshoring incentives under current law.

If foreign income is taxed at a lower tax rate than domestic income, the lower rate for foreign income would make it useful to have a per-country minimum tax, rather than a global minimum tax. This would ensure that haven income was discouraged for all companies, since income from high-tax countries would otherwise offset minimum tax due.

If the foreign rate is harmonized with the U.S. rate, a global minimum tax may work better, since all foreign income would be taxed at the U.S. rate, and there would be no incentive for haven income. High-tax foreign income would still reduce the tax burden on haven income, but since all foreign income would be taxed at the same rate as the U.S. rate, there would no longer be any general tax preference for foreign income relative to U.S. income.

Advantages of a lower per-country minimum tax

Consider the possibility of returning the U.S. corporate tax rate to 35 percent—its level prior to the TCJA—as proposed by several U.S. policymakers. In this circumstance, a lower per-country minimum tax is less burdensome on foreign income than a 35 percent rate, somewhat addressing company competitiveness concerns. For example, a 21 percent minimum is closer to current corporate tax rates abroad; the corporate tax rate for Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries averaged 22 percent in 2019.10

In general, U.S. companies will argue that it is difficult to compete with foreign companies that are under tax regimes that do not require minimum taxes in non-U.S. markets. For example, since U.S. companies face higher tax burdens operating in Ireland than many foreign companies do, they would be at a competitive disadvantage when serving the Irish market, when serving third markets from Ireland, when competing for foreign acquisitions, or when running a global business that is dependent on affiliated companies in global supply chains.

Companies have made overstated claims about competitiveness both before and after the TCJA. Under these regimes, there has been no evidence of serious competitiveness problems for the U.S. corporate community. After-tax profits were high in both historic and comparative terms; U.S. companies had a steady and disproportionate presence on global lists of the world’s top companies by any measure—whether sales, profits, market capitalization, or count; and U.S. corporate tax revenues as a share of GDP were far lower than those of typical trading partners.11 Furthermore, the most mobile U.S. companies earned reputations as world-class tax avoiders, such that companies in other countries felt disadvantaged.12

However, a regime with a 21 percent minimum tax due currently, with no opportunity to defer that tax, is far more burdensome on global operations than either pre- or post-TCJA law. Thus, company complaints may have some merits in this context. A lower rate on foreign income, such as a 21 percent or 28 percent rate in the presence of a 35 percent domestic tax, is a way of recognizing these potential competitiveness worries. While a lower foreign rate is a compromise relative to the full domestic rate, it will still undoubtedly meet substantial business resistance when viewed in comparison with current law.

An additional argument for a lower per-country minimum tax, rather than matching a higher domestic rate, is that it may prove easier to encourage other countries to adopt a minimum tax at that rate. Tax competition pressures would be lessened as more countries adopted a minimum tax regime, making economic activity and tax revenue less sensitive to tax rate differences across countries. Many prominent U.S. trading partners have shown interest in a minimum tax regime, and the OECD has proposed a minimum tax as part of its proposals on digital taxation.13

Advantages of a harmonized global minimum tax

If the foreign rate were the same as the U.S. domestic rate, there would no longer be any concern that U.S. tax policy prefers foreign income over domestic income. All income, regardless of source, would be taxed at the same rate, immediately. In contrast, any tax regime with a foreign rate lower than the U.S. rate would clearly prefer foreign income, tilting the playing field toward foreign operations.

Also, if foreign income were taxed at the U.S. rate, there would be less need for per-country implementation of the tax, which would lighten administrative and compliance burdens. Companies have complained that a per-country minimum tax would present administrative difficulties. Although these complaints are both overstated and convenient, a global tax is easier to administer. At any given tax rate, companies prefer global minimum taxes, since they lighten the burden of minimum taxes when tax rates differ across countries.

However, if the domestic rate were returned to its pre-TCJA level, there would be substantial concerns about the competitiveness of U.S. MNCs if foreign income were taxed at the same rate. As one example, if a U.S. MNC were taxed at 35 percent on its worldwide income as it was earned, but a foreign MNC were taxed under a territorial system that exempted foreign income, the U.S. company would be at a disadvantage if both were bidding on a foreign acquisition target. One possible solution is to combine these corporate policies with more robust capital taxation at the individual level, implementing a lower corporate rate—perhaps 28 percent—for both foreign and domestic income.

There are currently many proposals for strengthening capital taxation at the individual level. These range from relatively incremental changes—such as ending step-up in basis at death; strengthening estate taxation; raising rates on dividends and capital gains; ending the pass-through business deduction; and limiting contributions to tax free retirement and college savings accounts—to relatively systemic, broad proposals, such as adopting a wealth tax or mark-to-market taxation for capital income.14

The incremental proposals are much easier to adopt in the short run, although more systemic changes are certainly worthy of medium-run consideration once implementation and legal issues have been resolved. Regardless, it is important to remember that about 70 percent of U.S. equity income goes untaxed at the individual level, so the corporate tax remains an indispensable tool for taxing capital income.15

Anti-inversion rules and regimes

While there are tax provisions such as the base erosion and anti-abuse tax (BEAT) that attempt to discourage profit shifting by foreign-based MNCs, all of the above proposals risk discouraging U.S. residence for tax purposes, since U.S. residence is what triggers the taxation of foreign income. Thus, there is concern regarding corporate inversions—transactions that companies use to change their country of residence for tax purposes.

Preventing U.S. companies from reincorporating abroad is relatively simple if there is political will to enact strong anti-inversion measures. Already, bills proposed in Congress aim to do just that. One option is to adopt a strong management and control test, and there are other rules that could combat corporate inversions.16

There would still be concerns that foreign companies would face a tax advantage, but those could be combated through a stronger BEAT or other measures to reduce tax avoidance by foreign-based companies. Economists Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman suggest applying sales-based formulary apportionment to the global tax deficit of foreign companies in countries without minimum taxes; the tax deficit is the difference between the tax companies would have paid with a 25 percent minimum tax and their actual tax payments.17 This proposal would entail many complexities, but such a tax would raise additional revenue.18

Estimated revenue gains from international tax reform

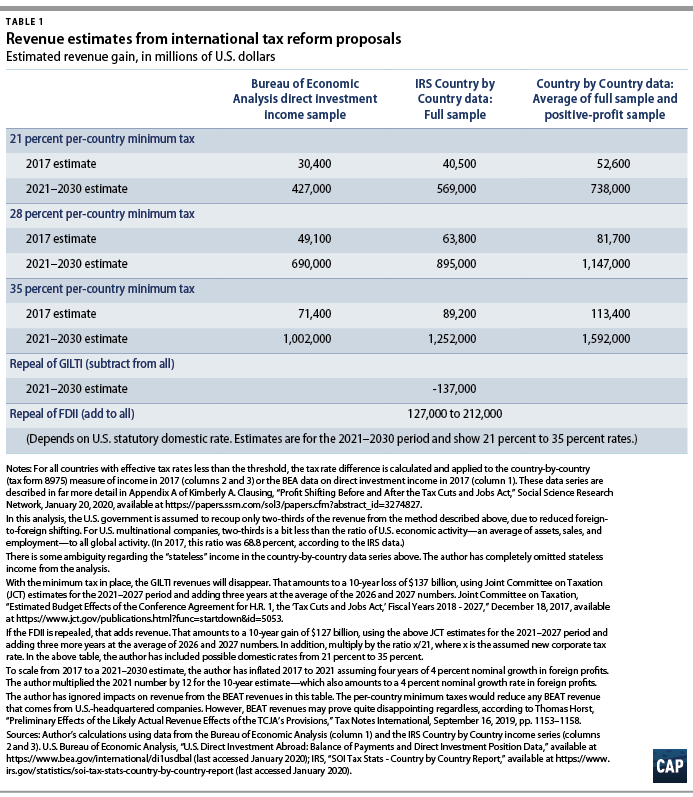

According to JCT revenue estimates, each percentage point increase in the U.S. corporate tax rate raises about $100 billion of revenue over 10 years. In addition, both the repeal of the FDII and the replacement of the GILTI tax with a more robust per-country minimum tax would raise substantial revenue. (see Table 1)

The estimates presented in Table 1 are built on several assumptions, detailed in the table’s notes; these assumptions are both cautious and in line with current literature in this area. The table’s first column shows estimates from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis data series on direct investment income; the second and third columns report series from the new IRS country-by-country dataset. The second column shows the full country-by-country dataset, and the third column shows a second set of estimates that averages estimates from the full dataset with those from a dataset that is confined to the companies that report positive profits.19 Multiple datasets are used to provide a range of possible estimates that are all based on high-quality data sources. The strengths and weaknesses of these data are discussed in the paper referenced in the first note of the table.

Table 1 does not include estimates for global minimum taxes. At any particular tax rate, global minimum tax revenues would be lower than per-country minimum tax revenues due to the possibility of cross-crediting. In addition, the further the minimum tax rate was from the U.S. rate, the more a global minimum tax would result in reduced revenue relative to its per-country counterpart.20 When foreign income is encouraged relative to U.S. income, there is a greater incentive to combine higher- and lower-taxed income streams from foreign countries, rather than earn income in the United States. Thus, unless the U.S. and the foreign rates are similar, an adoption of the per-country minimum tax will better stem profit shifting and protect the U.S. corporate tax base.

Notably, the OECD recently proposed an unspecified global minimum tax as part of its work on the digital economy,21 and there may be momentum for the adoption of minimum taxes elsewhere. The adoption of minimum taxes by foreign governments will generate revenue in the United States for the same reason that a U.S. minimum tax generates foreign revenues: Minimum taxes reduce the incentive to shift income from all nonhavens toward havens. Thus, it is also important for the U.S. government to productively engage in international efforts toward cooperation on this issue. Governments have much to gain from taming tax competition. And, because tax competition is far more of a problem for capital taxation than for labor taxation, stemming tax competition meets important progressivity goals. Despite the fact that capital income is far more concentrated than labor income, in recent decades, tax burdens on capital income have declined relative to those on labor income.22

Conclusion

Prior to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, the U.S. government collected less corporate tax revenue than its peer countries, despite the fact that U.S. corporate profits were at historically high levels. The profit shifting of MNCs was responsible for large revenue losses, and companies reported $2.8 trillion of accumulated earnings in just nine tax havens in 2017, on the eve of the passage of the TCJA.23 The TCJA responded with large corporate tax cuts, and the international provisions of the legislation had conflicting and ambiguous effects on profit shifting. The reforms to U.S. international tax rules detailed above would simultaneously raise corporate revenues, reduce profit shifting, and end the incentives to offshore economic activity that are embedded in current law.

Kimberly Clausing is a senior fellow at the Center for American Progress and the Thormund A. Miller and Walter Mintz Professor of Economics at Reed College.