On October 29, 2002, then-President George W. Bush signed the Help America Vote Act (HAVA) into law.1 The historic deadlocked presidential election of 2000 had just spurred the U.S. Congress to pass sweeping reforms to America’s election infrastructure. With bipartisan cooperation, Congress passed HAVA2 in order to prevent a repeat of the electoral crisis that ensued during the 2000 election.

Last year, when Russian agents tried to hack into U.S. election systems during the 2016 presidential election cycle, U.S. election infrastructure once again experienced a crisis that exposed continuing vulnerabilities.3 In light of the serious national security threats implicated by these unprecedented cyberattacks, it is time for Congress to act in the spirit of HAVA, 15 years after it was originally passed, and take immediate steps to shore up U.S. election infrastructure and invest in the security of America’s elections.

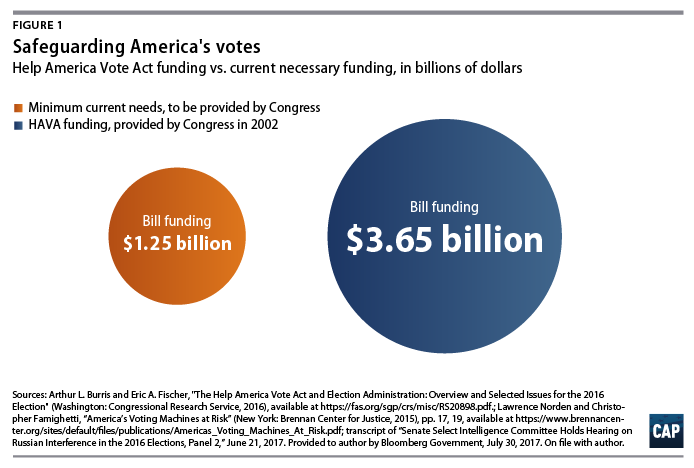

The post-2000 reforms embodied in HAVA revealed Congress’ intent to act boldly to protect one of the United States’ most bedrock constitutional rights: the right of every eligible American to cast a ballot that is properly counted. Through HAVA, Congress set forth requirements for voting equipment. Critically, HAVA authorized much-needed federal funding—$3.65 billion—to the states in order to meet the new statutory requirements.4 Due to this infusion of federal funds, voting machines became more reliable, though still not impervious to hacking or malfeasance. Today, many post-HAVA voting machines are more than 10 years old and nearing the end of their expected life cycles.5 These aging machines can have major flaws that render them insecure and vulnerable, which is unacceptable given U.S. adversaries’ attempts to hack into state and local election infrastructure.6

Now, in 2017, Congress can provide the next phase of necessary resources to help defend state and local elections systems from future cyberattacks for a fraction of HAVA’s $3.65 billion in funding. A sum of $1.25 billion over a 10-year period would provide the minimum necessary funds to cover a one-time cost of $1 billion to update outdated voting machines; $5 million per year to conduct threat assessments for voter registration databases; and $20 million per year to conduct nationwide risk-limiting audits for federal elections.7

These measures are vital for bolstering the United States’ national security, and funding them should be considered as necessary to protecting America’s democracy as military spending. For the cost of half of one B-2 Spirit bomber or four F-22 Raptor aircrafts—both of which are also used to protect the nation from foreign threats—Congress could take steps to secure the U.S. election infrastructure from foreign enemies.8 Surely protecting America’s election infrastructure from attack is as crucial to protecting U.S. democracy as paying for one-half of a military aircraft.

Federal lawmakers of both parties want to increase election security

Fortunately, there is bipartisan legislation in the U.S. Senate and U.S. House of Representatives that would take major steps toward protecting the United States’ election infrastructure: a commonsense provision introduced by Sens. Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) and Lindsey Graham (R-SC) as an amendment to the National Defense Authorization Act of 2017 (NDAA)9—and its House counterpart, the Protecting the American Process for Election Results (PAPER) Act, introduced by Reps. Jim Langevin (D-RI) and Mark Meadows (R-NC).10 This bipartisan legislation would allow states to request a Department of Homeland Security (DHS) security risk and vulnerability assessment and, after undergoing the assessment, would receive grant funding to implement security recommendations. Additionally, this legislation would require the U.S. Election Assistance Commission—an agency created by HAVA—to hold public hearings; work with experts to establish best practices for both election cybersecurity and election audits; and provide funding for states to implement those best practices. Moreover, the bill would task the DHS and the director of national intelligence with establishing strong lines of communication with state election officials regarding cyberthreats and would allow each state’s senior election official to receive a security clearance to receive briefings on cyberthreats. Finally, the legislation would require states to take steps toward ensuring that voter-verified paper ballot auditing systems are in place.

The Klobuchar-Graham legislation has not yet received a vote in the Senate, but it did garner the support of the U.S. Senate Committee on Armed Services Chairman John McCain (R-AZ)11 and Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) during debate on the NDAA.12 On the House side, the PAPER Act has not yet received consideration.13

Multiple national security leaders—of both political parties—have voiced support for this bipartisan legislation, including former Secretary of Homeland Security Michael Chertoff, former CIA Director James Woolsey, and former House Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence Chairman Mike Rogers, who wrote to Senate leaders and the Senate Committee on Armed Services leadership on September 11, 2017, to support the effort. The leaders stated, in part, “Although election administration is the province of state and local governments, the federal government has a responsibility to support the states and ‘provide for the common defense.’ … We do not expect the states to defend themselves against kinetic attacks by hostile foreign powers, nor should we leave them to defend against foreign cyberattacks on their own.”14 In the wake of this broad support from national security leaders and lawmakers of both parties, Congress should pass this legislation—coupled with an adequate funding authorization of at least $1.25 billion—immediately.

Notably, other election security legislation could soon be introduced, as additional federal lawmakers of both major political parties are stepping up to show leadership on the issue. For example, Sens. Kamala Harris (D-CA) and James Lankford (R-OK), both members of the Senate Permanent Select Committee on Intelligence and Senate Committee on Homeland Security and Government Affairs, continue to work on policies to improve election infrastructure.15

It is imperative that Congress act now

The United States has nonpresidential federal elections coming up in 2018 and the presidential election in 2020. The foundation of the United States’ democratic self-government relies on free and fair elections; thus, when the security of those elections is undermined, Americans may begin to question the value of their vote. This, in turn, damages U.S. democracy. Alarmingly, a July 2017 poll found that 1 in 4 Americans will consider not participating in future elections due to concerns over cybersecurity and the worry that their vote will not be protected.16

No one yet knows the full extent of Russian attempts to hack into state and local election systems in 2016. But credible evidence shows that Russians tried to hack at least 20 state election systems before Election Day and sent messages to 122 email addresses associated with entities likely involved in the management of voter registration systems in order to probe or infiltrate voting databases.17 Hackers did, in fact, breach election records in Illinois, where they tried to delete and alter voter information.18

Even worse, the 2016 election cycle may only be the tip of the iceberg of what may happen in future elections, according to intelligence experts and federal lawmakers.19 Russia may have used the 2016 cycle to find vulnerabilities in U.S. election databases to prepare for more aggressive intrusions in the midterm congressional elections of 2018 and the next presidential election in 2020.20 Other hostile actors, such as Iran, North Korea, and the Islamic State group, have also used cyberattacks or the internet to try to subvert Western democracies—and they may try again.21

Unfortunately, as evinced in a recent hacking simulation, U.S. election infrastructure—maintained principally by states and localities in more than 7,000 election jurisdictions nationwide—is not prepared to defend against future interference.22 These voting systems include inadequate cybersecurity measures for voting machines and databases; outdated voting machines; and a lack of verified paper ballots or records, which are imperative to conducting appropriate audits. To compound matters, most states and localities simply lack the necessary funds to address these problems.23

State and local officials increasingly recognize that protecting U.S. elections is not just a matter of ensuring fair elections but also one of national security that requires coordination at all levels of government—federal, state, and local. Before Election Day in November 2016, 33 states and 36 localities requested that the DHS assess their election systems.24 More requests have been made in 2017.25 DHS officials are attaching greater urgency to this issue. In January 2017, then-Secretary of Homeland Security Jeh Johnson designated state and local election systems as “critical infrastructure”26—like the banking sector and the electrical grid—and the DHS has established a coordinating council to work directly with states on bolstering election security.27 But under current law, these important steps do not provide local jurisdictions with the broad range of resources and funds to modernize their election infrastructure.

Conclusion

In light of these circumstances, Congress must seize the initiative now to fortify the security of U.S. election infrastructure. This is a rare chance for Congress to act in a bipartisan and timely manner. And as the 15th anniversary of HAVA infusing billions of dollars to upgrade voting machines approaches, there should be increased urgency for federal lawmakers to set aside partisan differences and pass much-needed election infrastructure legislation. Election security is a matter of national security, and these affairs historically have been above the political fray. Russian attempts to hack into the U.S. 2016 election, regardless of whom they favored or whether they were successful, dictate that Congress take decisive action to shore up the public’s confidence in the security of U.S. elections and help protect this country’s democracy.

Michael Sozan is a senior fellow supporting the work of the Democracy and Government Reform team at the Center for American Progress.