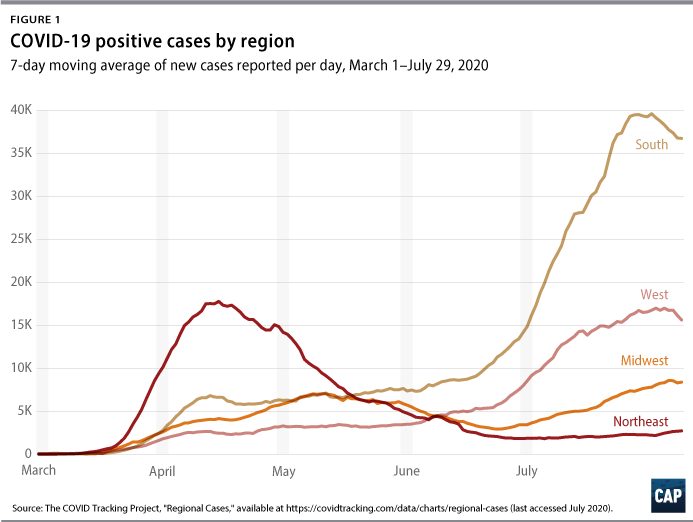

After states rushed to reopen their economies in late spring, coronavirus cases began to surge across most of the United States. At the same time, states in the Northeast have experienced declines in COVID-19 cases, deaths, and hospitalizations. Despite having been the epicenter of the U.S. cases throughout the early spring, this region now has a relatively low degree of new case incidence, even as transmission of the virus accelerates in other parts of the country—particularly in the South and West. (see Figure 1)

Public health experts agree that the rush to end stay-at-home orders without meeting public health benchmarks and the politicization of mask-wearing have created this surge. This report analyses the timing and scope of reopening measures to determine which specific actions were more likely to be the reason for the latest spikes. In particular, the following factors appear to be why the Northeast has had more recent success than the rest of the country in slowing the spread of COVID-19:

- The timing and duration of initial stay-at-home orders

- The timing and scope of reopening economic activity

- Individual behavior and local culture, which may have been influenced by local COVID-19 risks early in the pandemic and reinforced by local policy choices

In particular, this analysis finds that a key policy difference between the Northeast and other states is the timing of reopening bars and indoor dining, combined with the adoption of mask mandates before the lifting of stay-at-home orders. In addition, this report briefly compares these findings with the experiences of other countries, focusing on Japan’s successful approach to cluster-based contact tracing and public education.

Given this evidence, other states and the federal government must at a minimum work to quickly replicate these conditions throughout the rest of the United States. In addition to mask mandates, federal economic support directed to high-risk businesses and their workers can keep those companies financially viable, protect workers’ health and pocketbooks, and slow the spread of the virus.

The need for both the first and second wave of business closures was never inevitable. Like other countries around the world, the United States could have prevented high levels of community spread through swift and aggressive measures such as testing and tracing or promoted the adoption of personal hygiene habits such as social distancing and mask-wearing. Unfortunately, the federal government’s failure to act early on in the pandemic and states’ decisions to reopen too rapidly mean that targeted closures are again critical to controlling the spread of COVID-19 in the United States. This approach of targeted closures and attacking clusters is what is needed at a minimum in areas with substantial spread—but ultimately, local stay-at-home orders may also be needed to create the conditions under which this strategy could work.

Policy differences between the Northeast and other states

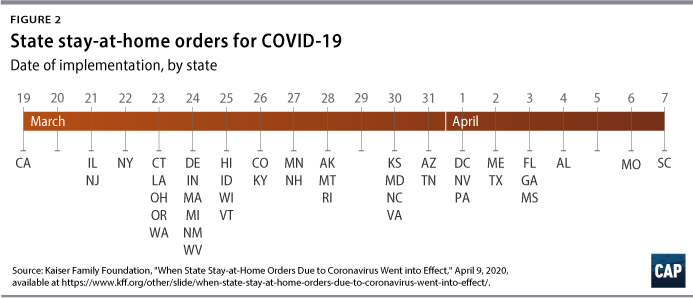

In the absence of clear federal guidance, states started implementing in March various social-distancing policies—starting with targeted recommendations for at-risk individuals and bans on large gatherings and culminating with stay-at-home orders. Over the next two months, more than 42 states and the District of Columbia had stay-at-home orders in place for at least some period of time; by June 9, all of these orders had been lifted to some extent. There remains enormous variation across states, as described below.

Differences in the timing and duration of stay-at-home orders

Generally, states in the Northeast implemented stay-at-home orders one to two weeks sooner than other regions, particularly Southern states. (see Figure 2) New York and Massachusetts had implemented orders by March 22 and March 24, respectively, whereas Arizona and Texas did not implement orders until March 31 and April 2, respectively. Rhode Island was the last of the Northeastern states with major spread to adopt a stay-at-home order.

The Northeast was also unique in that it was the only region in which all states implemented a stay-at-home order. (For the purposes of this analysis, the authors define the Northeast region according to the U.S. Census Bureau definition.) In the other regions, eight states—Arkansas, Iowa, Nebraska, North Dakota, Oklahoma, South Dakota, Utah, and Wyoming—never issued stay-at-home orders.

Washington state and California—which were early U.S. epicenters—were among the first several states with stay-at-home orders, and both states are again facing surges in COVID-19 cases. As discussed below, their subsequent decisions to allow the reopening of bars, restaurants, and other retail activity on a county-level basis canceled out the benefit of their early, decisive actions.

Given the impact that even a week of social distancing can have in reducing the spread of COVID-19, it is likely that these delays exacerbated eventual spread across the United States. In addition, state policymakers who delayed the adoption of stay-at-home orders until April may have reinforced differences in residents’ attitudes toward social distancing, as discussed below.

There are also differences between the Northeast states and other states in how long their stay-at-home orders remained in place. Not only were the Northeast states some of the earliest to adopt strict stay-at-home policies, but they also kept them in place until May or June and generally conditioned their termination upon a sustained decline in cases. Of the Northeast states, Rhode Island’s order was in place for the shortest period of time—for six weeks from March 28 to May 9. By contrast, Florida’s order lasted 30 days, and Texas’s was in place for less than a month. Colorado’s full stay-at-home order was similarly short in duration, but the state had imposed other social-distancing requirements for a longer period of time. In addition, Denver did not relax its stay-at-home mandate until two weeks after the statewide measure was lifted, and it and surrounding counties encouraged residents to remain at home.

The timing and scope of reopening economic activity

While both the start date and duration of the initial stay-at-home order differ between regions, simply looking at the day on when states announced the start of their reopenings does not fully explain the following divergent trends in transmission. Nor has the number of cases at the time of reopening correlated to a state’s ability to avoid future outbreaks. In fact, Northeastern states with high incidence upon their initial reopening—including the original epicenter of New York—have fared better than other states that reopened with lower incidence such as Arizona.

A comparison of states in the Northeast with a handful of other states—including some with early major outbreaks (California, Michigan, and Washington); some with recent outbreaks (Arizona, Florida, and Texas); and others adjacent to the region (Delaware and Maryland)—strongly indicates that the actions taken by states after their initial reopening date are most determinative of future outbreaks. Clearly, the speed and breadth of reopening matter greatly.

The Northeast states that have been most successful in keeping transmission under control as they have reopened have several key features in common. They were later to reopen in-person dining, and a few have yet to reopen bars. They also typically had a mask mandate in place a full month prior to the first phase of reopening. Combined with other factors, this strategy appears to be working: The Northeast states that were hardest hit in the spring—Connecticut, New Jersey, New York, and Massachusetts—now have lower new case incidence and positive rates than other states as well as compared with the nonrural states within the region. As discussed below, these findings are consistent with the growing scientific consensus about how the virus spreads.

Key reopening features in Northeast states linked with lower transmission

There is growing consensus that the virus that causes COVID-19 is spread not only through larger respiratory droplets but also via tiny droplets called aerosols. These aerosols can remain in the air longer and accumulate over time, increasing the risk of transmission in closed, indoor spaces. Masks limit the spread of both droplets and aerosols when worn by infected individuals. In addition, there is now some evidence that masks can reduce the amount of virus inhaled by the person wearing the covering. Table 1 features a summary of state policies on reopenings and masks.

Bar and indoor dining reopenings

Based on this evidence, bars and indoor dining pose unique risks of virus transmission; their very purpose ensures that people will be gathered—without face masks—while indoors. As Dr. Anthony Fauci said during a Senate testimony in June, such “congregation” inside bars is “really not good, really not good.” More than 150 COVID-19 cases, for example, have been linked to a single bar in East Lansing, Michigan. An unpublished study of Google location data found that the single policy associated with the greatest increase of social distancing was bar and restaurant closures. Conversely, according to a JPMorgan Chase analysis of credit card spending, in-restaurant purchases are the strongest predictor of increases in COVID-19 cases. Inside noisy bars and restaurants, patrons may speak loudly or yell in order to be heard, leading infected individuals to emit more aerosols and transmit the virus. Authorities in the District of Columbia issued warnings to about a dozen bars for having music louder than “a conversational level.” Inebriation presents another risk, as it potentially limits patrons’ judgment of COVID-19 risks and makes it challenging for bar staff to enforce social distancing.

For these reasons, it’s not surprising that states that have been slower to reopen bars and indoor dining locations have experienced lower rates of transmission than states that rushed to reopen these establishments. The earliest that bars were reopened in the Northeast was June, and Massachusetts has said that bars and nightclubs won’t reopen until therapeutics or a vaccine become available.

States in the Northeast also kept indoor dining closed through the end of May, with the exception of Maine, which allowed some indoor dining in mid-May. Indoor dining has yet to resume in New Jersey or in New York City. Rhode Island was the first state in the region to relax its stay-at-home order and among the earlier states to reopen indoor dining. The state’s cases have been rising in the weeks after indoor dining resumed, and its rate of new cases is more than double that of Massachusetts and New York.

Except for Delaware and Maryland, the non-Northeast states examined here allowed indoor dining starting in May. Texas was the first, with a May 1 reopening. Washington and California phased in reopening by county starting in May. Indoor dining resumed on June 5 for Washington’s three most populous counties, which are part of the greater Seattle area. Los Angeles-area restaurants were allowed to reopen for indoor dining by the end of May, and by mid-June nearly all counties in California had received state approval for in-restaurant dining. Gov. Gavin Newsom (D) later re-closed indoor dining in 19 counties and then statewide.

Among the nine non-Northeast comparison states, all except Maryland had reopened bars by June, with Arizona, Michigan, and Texas reopening bars in May. California, Colorado, Texas, Arizona, and Florida re-closed bars within the past several weeks. The danger of reopening bars and restaurants too soon is apparent in Michigan: After successful containment of a March outbreak concentrated in the Detroit metro area, cases rose again beginning in mid-June—just a few weeks after the state reopened bars and indoor dining. Due to “outbreaks tied to bars,” Gov. Gretchen Whitmer (D) re-closed bars and indoor dining in most of the state just one month after reopening them “to slow the spread of the virus and keep people safe.”

Adoption and timing of mask mandates

Both laboratory studies and real-world experiences overwhelmingly affirm that masks are effective at preventing the transmission of the virus. More specifically, a recent Health Affairs study found that mask mandates in 15 states and the District of Columbia were associated with declining COVID-19 growth rates and had a greater impact over time. In addition, some experts believe that masks may reduce the dosage of virus exposure for the wearer, resulting in less severe cases of COVID-19 for those who do become infected. As evidence mounted that masks can reduce the spread of the coronavirus, most states in the Northeast enacted mask requirements by early May. With Vermont’s mask mandate effective as of August 1, New Hampshire is the only remaining state in the region without a mask mandate; both states continue to have a low level of cases, likely in part because they are among the more rural states in the region.

In contrast, California and Washington, despite also being early U.S. epicenters, did not mandate masks until the second half of June. Texas adopted a mask mandate in July, and Arizona and Florida still do not require masks. All of these states experienced surges in cases in July.

The contribution of testing and tracing to the Northeast’s success

In contrast to nations such as South Korea, the United States has struggled to expand testing and implement contact tracing. After initial roadblocks in test supply and access nationally, and despite recent concerns about delays in test results, states—particularly those in the Northeast—have made substantial progress in scaling up their testing and contact-tracing programs.

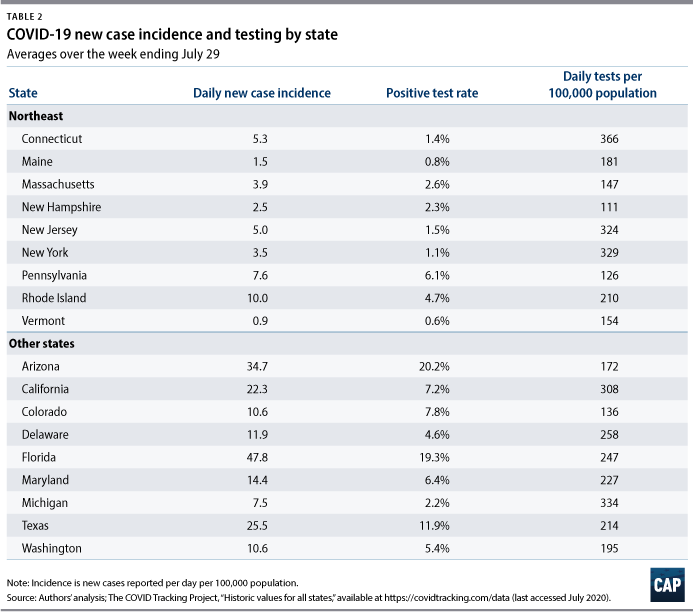

Testing and tracing do not seem to be the primary driver of Northeast’s success. Public officials and health care workers in the region struggled to obtain sufficient supplies for testing to combat the severe outbreaks in the spring. As the Northeast worked to establish control over the spread of the virus, the volume of testing rose and then leveled off in the region. The positive test rate in the Northeast has remained low over the past several weeks, indicating that states in the region are conducting sufficient testing. The positive test rate in most other states is well above the World Health Organization’s recommended level of 5 percent for reopening. With positive rates near 20 percent, Arizona and Florida need to conduct far more tests to adequately monitor outbreaks.

Overall, the level of contact-tracing activity appears higher in the Northeast than in the South. According to the CovidActNow database, states in the South are contacting fewer new cases than those in the Northeast. The percentage of cases who provide information about their contacts is lower, and the percentage of contacts who are reached—a superior measure of effectiveness—is unknown.

Nevertheless, states in the Northeast have not had uniformly successful experiences with contact tracing. Rhode Island was among the first to have a program in place. Gov. Gina Raimondo (D) established public-private initiatives “very early on” in the pandemic to develop “aggressive testing, very aggressive contact tracing.” The state also developed an app that keeps a digital “location diary” and helps public health personnel maintain contact with people in isolation. Despite these efforts, COVID-19 cases have risen in the state after it eased up on social-distancing measures.

Massachusetts and New York have maintained relatively low incidence plateaus despite challenges with contact tracing. Massachusetts launched its program in April and announced last month that it was scaling back the program. Transmission is dwindling in the state, but the program was also criticized for being unreliable. New York City’s contact-tracing program hired around 3,000 people in late May, yet only around 35 percent of positive cases provided information to the program in its first two weeks.

The contribution of nonpolicy factors on community spread

Decisions by individual people, businesses, and the local culture also appear to play a role in mitigating the transmission of the virus. Many of these factors may reinforce local COVID-19 mitigation policies, and residents’ tolerance for mandated business closures and social-distancing rules can also support or constrain local policy choices.

Politicization: The politicization of mask-wearing and other mitigation measures appears to be influencing both policy decisions and individual behavior. For example, respondents who identified as Democratic-leaning were more likely to wear a mask, according to surveys by Pew Research Center. This may be in part due to the fact that Democratic-voting counties were also harder hit by the virus early on and were more likely to impose stay-at-home orders.

The overall politicization of the COVID-19 crisis appears to be deepening preexisting distrust of public health officials and undermining contact-tracing efforts. Further exacerbating this issue, the racist history of public health experiments on Black people may cause distrust toward contact tracers.

Salience: This may also play a role in whether people adopt hygiene and social-distancing habits as well as support stricter policies. Because the Northeast was hit hard by the virus early on, residents of that region may be more receptive to policy and behavioral changes. One expert in Massachusetts noted that residents “were scared and understood the need for precautions.” As of April, people in the Northeast were twice as likely to personally know someone who had COVID-19 (42 percent) than people in the West (21 percent), according to polling by Pew Research Center. Similarly, people in the Northeast and Midwest were more likely to know someone who had been hospitalized than residents of the South or West.

Throughout the United States, people are more likely to wear a mask and more likely to report that they see others wearing masks in counties that have experienced greater health impacts related to COVID-19. For example, a March outbreak in the Denver area may have spurred Coloradans to wear masks and social distance.

Climate: Some experts have pointed to a link between COVID-19 hotspots and regions that are using higher levels of air conditioning. Hotter temperatures drive people indoors to cooler but more poorly ventilated spaces. In fact, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has recommended that homes and businesses open windows for increased circulation of outdoor air in order to reduce transmission of the virus. The rash of new cases that emerged in the Sunbelt in July contradict President Donald Trump’s unfounded speculation in April that heat and light would diminish the virus.

Seroprevalence: Some observers suggest that herd immunity will play a major role in slowing transmission, particularly in areas of the country already hard-hit by the virus. Evidence from seroprevalence studies, however, suggest that the vast majority of the population has not yet developed COVID-19 antibodies, even in the Northeast. The CDC said in late June that it believes that approximately 24 million Americans had been infected with COVID-19—equivalent to about 10 percent of the U.S. population. Among the large-scale seroprevalence surveys maintained by the CDC using commercial lab-based samples, the places with the highest antibody levels documented to date are New York City (23 percent as of late April and early May) and Louisiana (5.8 percent as of early April). Herd immunity for COVID-19 may not occur until 70 percent of the population has become infected, assuming that a COVID-19 infection confers long-lasting immunity—a feature that has not yet been proven.

What other countries have in common with the U.S. Northeast

New case incidence generally remains higher in the U.S. Northeast compared with that in countries in Western Europe. Public health experts have pointed to America’s “piecemeal, politicized approach” to the virus as the reason why it has lagged behind its Western European peers. Most Western European nations acted quickly to lock down and to test and trace. Even Spain and the United Kingdom—which were slower than other European countries in their initial responses and which faced uncontrolled spread—nevertheless achieved lower incidence after locking down. (Cases have risen again in Spain, which has the highest rate of new cases in Europe.)

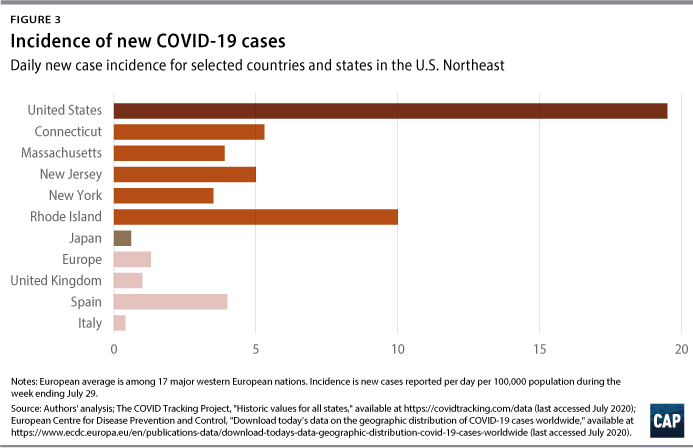

Combining data across 17 major countries in Western Europe, the authors find that there were fewer than two new positive cases reported per day per 100,000 population in the seven-day period ending July 29 (1.4 cases). Of the 17 countries, only Belgium (2.3 cases), Portugal (2.1 cases), and Spain (4.6 cases) had rates above two cases per day per 100,000 population. The incidence in the United States over the same period was 19.5 new cases per day per 100,000 population nationally but far lower in states in the Northeast, according to the authors’ analysis of COVID Tracking Project data. (see Figure 3) While incidence numbers are partly dependent upon the level of testing—more testing can lead to detection of more cases—the United States still has a higher all-time positive rate than most European nations despite conducting more tests per capita than any other country.

Japan’s successful coronavirus response

While Japan has successfully limited COVID-19 cases and deaths, unlike the United States, its policy environment bears some resemblance to U.S. conditions early in the pandemic. Japan did not impose a lockdown and lacked the authority to order one. Like the United States, Japan does not have a digital contact-tracing program and conducted relatively few tests per capita. It instead relied upon manual contact tracing carried out by the country’s 450 local public health centers to identify clusters of infections. Japan’s success can be attributed in part to voluntary changes: Many businesses shut down by choice, and mask-wearing became universal without a mandate. Japan’s public health response emphasized individual behavior, instructing individuals to avoid the “Three Cs”: closed spaces, crowded places, and close-contact settings. In July, Japan experienced a new series of outbreaks, some linked to hostess clubs where people gather and drink. While the spike in cases in Japan is nowhere near U.S. levels, it illustrates the hazards of reopening high-risk venues even when transmission is relatively low.

While the U.S. government missed its opportunity to elicit a wave of voluntary closures or mask-wearing in the early stages of the pandemic, it is not too late for federal, state, and local leaders to generate conditions similar to those in Japan through policy by mandating masks and ordering targeted closures until transmission is lower. In addition, Japan’s experience highlights that contact tracing need not be implemented as a national program to be successful. Given their resource constraints, U.S. public health officials should consider adapting a similar approach to contact tracing, focusing on identifying and tracing infections related to clusters and urging temporary closures of venues and gatherings that are likely to lead to super-spreading events.

Recommendations

The Northeast’s relative success in bringing COVID-19 under control, as well as the runaway spread of the virus in other regions of the country, serves as a lesson that policymakers need to take swift and decisive action in order to reduce community transmission and prevent future waves over the coming year.

Close indoor dining and bars

Given the risks that bars pose and the fact that they have been pinpointed as the sites of major outbreaks, states should consider following Massachusetts’ example by keeping bars closed until an effective COVID-19 vaccine or therapy is widely available. Similarly, because reopening indoor dining, even at limited capacities, is linked to increasing incidence, states should also reevaluate their decisions to allow restaurant patrons to dine indoors, especially in hotspots.

Federal lawmakers should continue to provide robust unemployment insurance for workers and offer financial support for bars and restaurants that is better targeted to meet their needs than the current Paycheck Protection Program. Support for those businesses should help cover their fixed costs during mandated closures or capacity restrictions for public health reasons. Doing so would reduce pressure on business owners to reopen prematurely and allow employees in the industry to avoid high-risk work environments. States and cities that reopen too soon risk resurgences of the virus and the need for another round of closures. A separate CAP analysis of states’ initial responses to the pandemic found that states with longer stay-at-home orders not only better managed the spread of COVID-19 but also did not have worse economic outcomes.

Monitor other potentially high-risk venues

Officials should closely monitor indoor venues—such as gyms and places of worship—where people generate high emissions of droplets and aerosols while exercising or singing. Current science and local incidence could justify additional closures or other public health measures such as capacity limits, mandating that activities move outdoors, and requiring masks.

States have also allowed businesses that inherently require people to be in close proximity, such as hair and nail salons, to reopen. There have not been any reports of major COVID-19 outbreaks traced to hair or nail salons in the United States, although these settings are likely to pose a greater risk than other nonessential businesses where social-distancing measures can be more consistently maintained. This success to date offers further evidence that compliance with hygiene and social-distancing protocols, including continuously worn masks, can minimize risk relative to venues such as bars and restaurants. A CDC-published case study of two COVID-19 positive hairdressers who did not infect their clients suggests that face-coverings can help prevent transmission. Given the potential for lax compliance and enforcement of such measures, however, officials should continue to pay close attention to these businesses.

States must also monitor whether their restrictions on indoor gatherings are sufficient. For instance, a recent cluster of new cases in New Jersey linked to indoor parties near the Jersey Shore further demonstrates the importance of ongoing vigilance in tracking the virus, enforcing existing rules, and educating the public about the significant risk posed by groups gathering indoors, especially without masks.

Mandate masks

Given the growing pool of evidence that face masks are among the most effective ways to contain the spread of the virus, mask mandates are an essential tool to reduce transmission in public places. Governors and mayors who have not already done so must implement state and local mask mandates, publicize these rules, and ensure that all residents, especially lower-income individuals, have access to masks at no cost to them. Congress should make financial relief for businesses during the pandemic conditional upon mandating masks for both employees and customers.

Adopt cluster-based contract tracing

With reports of long turnaround times for COVID-19 test results, prospective contact tracing—which seeks to identify people who were in contact with an individual who tests positive—is losing its value. In addition, staffing and funding shortages have hampered contact-tracing efforts. State and local governments should put resources behind the Japanese cluster-based contact-tracing model.

Recent evidence has shown that a small number of people are responsible for the majority of cases due to the ways their bodies multiply and emit the virus as well as the risk of activities in which they engage. Such individuals carry and emit higher viral loads than others, becoming what The New York Times describes as “virus chimneys, blasting out clouds of pathogens with each breath.” Perhaps more importantly from a contact-tracing perspective, many clusters of cases are traceable to high-risk events or activities that occur in an enclosed space, with conditions worsened by poor ventilation, longer duration, large crowds, or forceful exhalation due to yelling, singing, or exercising.

Japan’s cluster-based contact-tracing model combines testing and interviews to link cases and look retrospectively for chains of transmission. It then uses patterns in that information to identify “sources that have a potential to become a major outbreak.” Some U.S. cities and states are already implementing similar procedures, although they may not be aware of this particular model. For example, Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, has improved its ability to hone in on high-risk venues thanks to the knowledge gleaned from its contact-tracing program. State and local governments must make a more concerted effort to focus on preventing super-spreading events.

Conclusion

Not only did the federal government fail to act quickly enough to prevent infections from spiraling out of control, but many states also reopened high-risk venues and businesses too soon. Those areas currently facing uncontrolled spread of the virus must take swift action to slow transmission, using the approaches that were most successful in the Northeast as well as in other countries. These actions must include, at a minimum, near-term targeted closures of super-spreading venues such as bars and mandating masks as well as longer-term investments in cluster-based contact tracing.

Keeping businesses shuttered for weeks or months should be the last resort for containing COVID-19, as other countries have demonstrated that strategies based on testing, tracing, and isolating are effective. The insufficient public health infrastructure and the recent degree of community spread in much of the United States, however, means that the United States cannot currently manage the virus through testing and tracing alone. Many state and local officials have no choice but to close and monitor high-risk venues, including indoor dining and bars, if they want to contain infections. Indeed, even more aggressive measures may need to be taken to drive transmission down to a level where this strategy would work. The goal of business closures is not to suppress economic activity. On the contrary, it is the only way to solve the public health crisis that is blocking the U.S. economy’s path to recovery.

At the Center for American Progress, Emily Gee is the health economist for Health Policy; Aly Shakoor is an intern for Health Policy; Maura Calsyn is the managing director of Health Policy; Nicole Rapfogel is a research assistant for Health Policy; and Topher Spiro is the vice president for Health Policy and a senior fellow for Economic Policy.

The authors thank Eva Gonzalez, Jerry Parshall, and Thomas Waldrop for their research assistance.