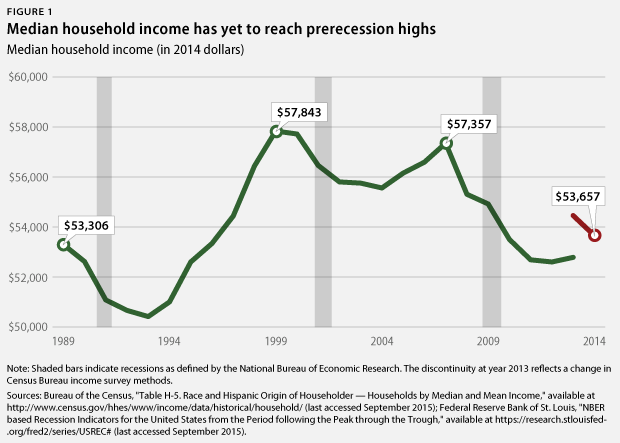

The new data released today by the U.S. Census Bureau show that America’s middle class is still struggling to fully recover from the Great Recession and more than four decades of unequal growth. Typical household incomes remain far below 1990s highs and, in fact, are close to the level they were in 1989. Meanwhile, middle-class families struggle to keep up with the rising costs of key components of the middle-class lifestyle.

The precarious position of the middle class is plainly visible when examining trends in the national median income. The real median household income in 2014 dollars fell a statistically insignificant $805 in the past year, from $54,462 in 2013 to $53,657.*

Typical household incomes have been effectively stagnant nationally since reaching their postrecession lows in 2011, with no statistically significant year-to-year changes. This is unacceptable considering the ground that middle-class families have to make up: Incomes have been falling or flat since 1999’s peak at $57,843, nearly $4,200 more than families took home in 2014.

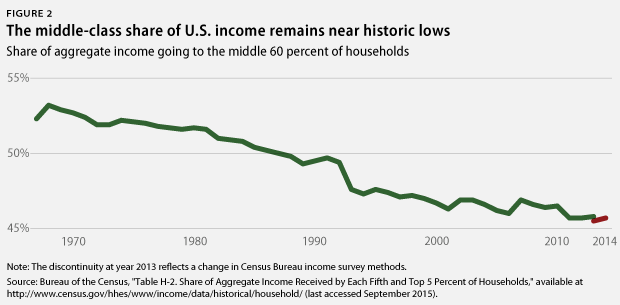

While middle-class incomes have flatlined, the economy has certainly grown since the recession ended. Unfortunately, not all families are seeing this economic growth make its way into their paychecks, even though the losses during the recession were shared among all levels of income. In 2014, the top 20 percent of households took home a majority of U.S. income, 51.2 percent. And a large share of that income was concentrated among the richest 5 percent of households, which received 21.9 percent of the nation’s income in 2014. That means that the middle class and those living in poverty took home less than half of the economic pie, despite constituting the vast majority of the population. Unless further action is taken to ensure that all Americans benefit from the growing economy, these long-term trends all point to increasing economic inequality and a shrinking middle class.

Middle-class incomes failing to keep up with gains for the rich is not a new story. In fact, the share of national income going to the middle 60 percent of households has been trending downward over the past few decades since its peak in 1968. While middle-class households took home a majority of U.S. income then—53.2 percent—their share has fallen dramatically by 7.5 percentage points to just 45.7 percent in 2014. This is not an insignificant amount of money: 7.5 percent of U.S. aggregate income is $708 billion, meaning that if middle-class families were still receiving the same share of income as families did in 1968, their annual incomes would be more than $9,400 higher on average.

The strength of the American economy depends on a thriving middle class. These Census Bureau data make clear that there is still work to be done to ensure that all Americans fully share in the economic recovery; we must reverse the decades-long decline of the middle class. Policymakers should act to improve workers’ wages by increasing the minimum wage and reducing barriers that keep workers from collectively bargaining. Tax reforms should be crafted to benefit the middle class, not those who are currently enjoying the majority of income growth. Lawmakers should increase public investments to help create new jobs that pay middle-class wages and institute workplace protections, such as paid leave, that would help keep people in the labor force. Taking action is critical. America’s middle class—and its entire economy—cannot afford to continue on a path in which the benefits of economic growth are not broadly shared.

Alex Rowell is a Research Assistant with the Economic Policy team at the Center for American Progress. David Madland is the Managing Director of the Center’s Economic Policy team.

* Authors’ note: The Census Bureau recently introduced new methods for surveying income. Our 2013 income measure is from the Census Bureau subsample that received redesigned income questions. In 2013, the subsample who received the redesigned questions were shown to have a higher median household income than those who received the traditional questions. While this methodology is consistent with the 2014 data, this change could affect long-term data comparisons. See Appendix D of the Census Bureau’s “Income and Poverty in the United States: 2014” for more information.