Social impact bonds—sometimes known in the United States as “Pay for Success” agreements—are as complex as they are innovative. Social impact bond agreements require cooperation between government agencies, social service providers, impact investors, and external organizations—sometimes called intermediaries. Aligning the interests of so many disparate actors is no easy task, but part of the appeal of social impact bonds lies in the benefits of getting different sectors to cooperate and work together to achieve beneficial social outcomes.

What are social impact bonds?

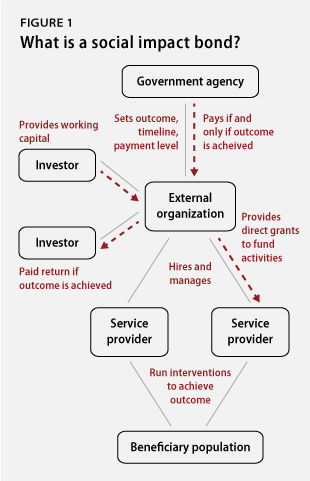

Social impact bonds, or SIBs, are an innovative new financing mechanism for social programs in which government agencies pay for programs that achieve specific social outcomes—but only after those outcomes have been achieved and verified. Nongovernmental investors pay the upfront costs of the programs in exchange for a return on their investment if the programs are successful. Under these arrangements, a government agency defines an outcome it wants to see achieved relative to a specified population over a set period of time—for instance, a reduction in the rate of recidivism by 10 percent over five years among nonviolent offenders in a prison system. The government agency contracts with an external organization that pledges to achieve the specified outcome or outcomes and promises to pay an agreed-upon sum if the organization is successful. The external organization then raises money from socially minded investors to fund social service providers. If the outcome is achieved, the government agency pays the external organization, and the investors receive a return on their principal. However, if the outcome is not achieved, the government pays nothing.

SIBs first took root in 2010 in the United Kingdom, where they are currently being used to finance interventions to reduce recidivism and homelessness, among other issues. In the United States, experimentation with social impact bonds has begun. New York City and Massachusetts have used them to attempt to reduce recidivism among juvenile offenders, and Utah has announced it will use them to expand access to early childhood education. The state of New York has launched a social impact bond to reduce recidivism, but it is also looking to improve workforce outcomes for adult offenders.

Collaboration, when done well, allows organizations to pool resources and expertise, thereby achieving more together than any one institution could achieve on its own. Before contracts are signed and work begins, organizations must come together to explore what it might look like to work together. Many factors determine whether a program will succeed or fail, particularly when it involves aligning different types of organizations, each with its own accountability structure, financial and human-capital resources, and institutional goals.

As interest in social impact bonds continues to accelerate across the United States and around the world, many institutions are considering whether and how to take advantage of this new innovation in social finance. Limited data on the effect of social impact bonds exist, since the first projects that made use of SIBs are still underway. For example, the first such agreement in the world launched in the United Kingdom in 2010; this project to reduce recidivism among nonviolent offenders at HM Prison Peterborough is not yet complete.

Furthermore, social impact bonds also carry considerable risks, especially for investors. Even foundations with long histories of assessing social impact face challenges in assessing a given social impact bond deal. Potential investors are still developing important questions:

- How can an investor apply due diligence to an unproven financial instrument funding social interventions, as such instruments are often difficult to scale or replicate even in the most capable hands?

- Without adequate grounding in evaluation methodology, how can an investor judge the evidence base of a program it’s being asked to finance?

- How can an investor be certain that government will follow through with its support of a successful social impact bond, especially if the term of the deal straddles an election year?

To date, the investment size of most social impact bonds has been relatively small—less than $20 million. The first in the United States, in New York City, was financed with $9.6 million from Goldman Sachs. But as social impact bonds become larger and more complex, many deals will rely on multiple investors from different types of financial institutions. We are already seeing this trend unfold, evidenced by the January announcement of a SIB for juvenile justice in Massachusetts. That deal blends private, philanthropic, and grant dollars to pay the upfront costs of the interventions.

Building relationships to build communities

Recognizing that relationship building will play a critical role in collaborative investment in social impact bonds, the Center for American Progress and the Council on Foundations jointly organized two discussions to bring together different types of potential SIB investors: foundations; Community Development Financial Institutions, or CDFIs; and investment firms focused on social impact, including wealth management advisors and the community development divisions of large investment banks. All discussion participants worked at institutions focused on delivering both social impact and financial returns.

The goal of the meetings was to spark discussion about what incentivizes each investor type to consider participation in a social impact bond. The discussions centered on two themes: the importance of bridging the perception gap between different investor types and the role that government and public policy can play in facilitating investment in social impact bonds. This issue brief focuses on the former. The latter is covered in a separate CAP issue brief, “Investing for Success: Policy Questions Raised by Social Investors.”

The findings outlined in this brief are from the two meetings noted above and from a series of one-on-one phone conversations with most meeting participants in advance of the events. During the phone calls, each participant was asked to consider his or her investor group—foundations, CDFIs, and social impact investment firms—and share what that specific type of investor would want the other organizations to know about it prior to beginning a conversation about collaboration. These phone conversations helped prime participants to think about some of the stereotypes and misconceptions that can impede collaboration. Moreover, they allowed CAP and the Council on Foundations to better understand how CDFIs, foundations, and social impact investment firms operate.

The two meetings provided participants with the opportunity to hear reactions of other potential social impact bond investors and share their own. Each meeting included about 20 participants, including four to five representatives each from the three types of investment organizations and a small number of representatives from intermediary organizations and government. Sonal Shah, former director of the White House Office of Social Innovation and Civic Participation, was the facilitator at both gatherings.

The meetings were structured around two case studies, written by independent consultant Steven Goldberg, which outlined hypothetical SIB investment opportunities. In drafting the cases, we made deliberate choices to elicit conversation on issues such as risk, time horizon, intervention scale, and evidence level. When discussing the fictitious cases, participants were encouraged to make comments that reflected how an abstract foundation, a CDFI, and a social impact investment firm—rather than their particular organizations—might react if presented with an investment opportunity like those outlined in the case studies. This approach aimed to prevent participants from feeling pressured to speak on behalf of their organizations.

Going into these discussions, we considered the variety of roles that each interested investor could play in a social impact bond. Foundations, for example, could opt to convene other organizations or provide content expertise; provide grant support to scale a promising program or fund an evaluation; offer guarantees for some portion of other investors’ capital; or invest directly, with returns on investment ranging from 0 percent to market rates or beyond. CDFIs could play an intermediary role as aggregators and distributors of capital or as capacity builders for service providers.

The case studies

Investment case studies

Using social impact bonds to prevent child abuse and neglect

The scenario: We proposed a $20 million social impact bond to prevent the children of 2,500 families from entering foster care over a period of five years, with a proposed intervention that was termed “promising” but had not yet been determined to be a “gold-standard” or a “top-tier” evidence-based intervention. In this situation, the cost of foster care for the state in 2011 was $111 million and resulted in 2,700 placements. It is estimated that reducing the need by the level mentioned above would save the state $54 million over five years. Depending on the terms of the deal and its successful outcome, the investors would be repaid their capital investment plus 5 percent or 10 percent of the state’s savings, for a return of $1.6 million or $4.3 million.

Using social impact bonds to fund early childhood education

The scenario: We proposed scaling high-quality, early childhood classroom instruction, which is considered a top-tier evidence-based practice, for 5,000 low-income 3- and 4-year-olds in a state that does not currently have a state-funded public pre-K program. The program cost was $60 million over seven years. In this situation, a cost-sharing agreement between the state and federal governments was proposed to repay an investment of $47.5 million, with a potential return on investment of 5 percent, or $2.25 million.

Wealth management advisors could match their clients to social impact bond deals that fit their social missions and needs for expected rates of return. Investment firms could provide capital for projects serving low-income communities in the geographies they serve. While there are many different roles that each investor group could play, the nonprescriptive structure of the case studies does not set roles for the potential investor types.

The discussions at the two meetings provided valuable insight into how different types of investors view their roles in social impact bond transactions, but it must be acknowledged that there is a limit to what can be extrapolated from the comments of these 40 participants. The sample size is small, and the participants were primarily responding to two case studies of SIB transactions—though many participants expanded the scope of the conversation beyond the case studies. The majority of participants, all of whom had basic knowledge about how SIBs work, are exploring investment opportunities, though some are skeptical of the tool. And because the aim was to focus on the relationship among investors of the types that would pay the upfront costs in social impact bond agreements, the primary voices in the conversation came from private investors rather than from government, intermediaries, service providers, or evaluators, all of which play important roles in making social impact bonds possible.

With these limitations in mind, the two meetings underscored two basic issues that will be critical to the ultimate success or failure of the social impact bond as a financial mechanism in the United States. First, each of the different players at the table must clearly communicate their own motivations, limitations, and abilities as well as seek to understand the same of other actors. Second, peer networks have a powerful role to play in both spreading knowledge about social impact bonds and facilitating potential co-investment in individual agreements.

Understanding different investors

Before working with different types of institutions, it is important to understand how and why each institution operates the way it does. The one-on-one calls with participants prior to the meetings drew out key considerations that each type of investor—foundations, CDFIs, and investment firms—would want the other investors to know before collaborating on a given investment.

The phone conversations made it clear that mission plays a crucial role in determining whether the collaboration makes sense. According to the interviews, a foundation often decides whether to get involved based on fit with its mission, strategic priorities, and programmatic areas of focus. Similarly, wealth management advisors emphasized a need to consider the individual mission and risk portfolio of each client.

Several of the CDFIs and foundations interviewed noted the talent of their staffs. CDFI staff provides technical assistance along with the diligence, structuring, and reporting for deals. The staff of foundations pointed out that they have intellectual capital to share, and they want to be involved early in the process. And foundation participants noted potential collaborators should not view foundations as checkbooks but as thought partners who have ideas and knowledge to contribute.

Additionally, participants said collaborators should not assume that CDFIs and foundations always have grant or investment capital available. The capital available for CDFIs to deploy depends on the capital invested in the organization. Foundation budgets are often committed far in advance, so a foundation might not have the flexibility to make an immediate grant or investment.

The foundation staff also pointed out that potential collaborators should not assume foundations are exclusively interested in using any one type of capital: They have the ability to make grants, which require no payback; program-related investments, or PRIs, which are investments that focus on a charitable mission and range from 0 percent to below-market rate returns; and mission-related investments, or MRIs, which intend to achieve a market-rate return while advancing the foundation’s mission. Internally, most foundations split investment and grant-making functions into separate departments, which might mean different decision-making processes and priorities.

The topic of risk came up among all investor types. Respondents who represented large investment houses noted that their firms are generally risk adverse and expect a return commensurate with the level of risk. The wealth managers stated that they often have clients with a range of tolerance for risk. According to CDFI staff, foundations or the public sector often assume risk when private investors are unwilling to do so.

However, it is important to keep in mind that not all organizations and individuals will accept high risk. The foundation staff stated that other collaborators should not assume that foundations will assume all of the risk in the deal or that risk should be shared among investors. While some foundations might be interested in using grant, PRI, or MRI capital for a risky investment, not all are.

Finally, the foundation and CDFI staff interviewed brought up the importance of sustainability. When considering work on an initiative, a foundation will often consider whether the initiative can be sustained over time and how it relates to the foundation’s other priorities and to observable societal changes. CDFIs brought up the issue of sustainability less around the outcome of the initiative and more as a question about SIBs as a financial product. Because each social impact bond transaction takes a considerable amount of resources to negotiate, the CDFIs noted that it is commonly preferred to have a product or broad fund that can support multiple transactions.

Importance of networks

The one-on-one calls offered a glimpse into how each investor type wants to be understood by other investors, but the discussions underscored just how instrumental networks are to success. Given the complex structure of social impact bonds, potential investors can greatly benefit not only from understanding one another but also from calling on the expertise within their networks. That is to say, no one entity has everything needed to address the problems it strives to solve. Looking at social impact bonds through this type of lens allows each group to bring its nonfinancial resources to the table to strengthen the collaboration.

Participants repeatedly noted the importance of knowing where to turn for guidance. During the joint discussion meetings, when an issue arose that the group at the table did not have the expertise to address, the conversation quickly turned to identifying the best organizations and people to provide guidance and subject-matter expertise. For instance, in the case study that revolved around preventing child abuse and neglect, which had a low level of evidence about the effectiveness of the intervention, participants indicated that they would seek out subject-matter experts to find out how the intervention compares to other programs.

Cultivating a network that extends beyond an individual’s or an organization’s area of expertise increases an investor’s ability to conduct solid due diligence to determine how or whether to enter an investment collaboration. No organization can be an expert on every issue, community, or geographical area, and it is important to recognize the limits of an organization’s knowledge. The investment firms, CDFIs, and foundations all appreciated being able to call on experts to more deeply understand potential investment opportunities and assess risk.

In addition to identifying issue expertise, networks enable investors to understand the bigger picture beyond the specific transaction under consideration. Most social problems do not exist in isolation, and having a solid understanding of other contributing factors, the community conditions, and the policy environment equips investors to make better, more informed decisions.

Foundations may be particularly well suited to facilitate these networks, given that they have strong relationships with the public, private, and nonprofit sectors. Foundations often know the other public and private funders that serve a particular geographic or issue area, allowing them to map out the interventions and resources that currently exist and are available. Beyond intellectual capital, place-based foundations can bring conversations to the community level to garner input from a range of stakeholders with different perspectives on how best to tackle a given problem.

Participating foundation leaders emphasized the need to look beyond one service provider or one intervention, as individual social problems are often closely enmeshed with others. For instance, improving education outcomes may require that attention be paid to the health, safety, and economic conditions of communities, among other issues. Furthermore, the foundation leaders described a desire to drive systems change in communities and expressed hope that investing in a social impact bond could contribute to that goal.

CDFIs and the community development divisions of large investment firms have cultivated networks for delivering capital to low-income communities. Some participants cited their involvement with Low-Income Housing Tax Credit transactions as a reason why both types of investors—CDFIs and investment firms—would bring knowledge and experience about facilitating multistakeholder investments.

Conclusion

As conversations about social impact bonds continue, it is helpful to understand what drives potential collaboration among investors. Since each institution has multiple ways in which it could participate, it is not useful to make assumptions about whether or how any one organization would want to collaborate. Taking time to get to know an organization’s mission, staff talent, available capital, appetite for risk, relationship with government, and sustainability goals can help bridge the perception gap among potential investors. Participants at our discussions highlighted the role of networks in identifying expertise and understanding the bigger picture beyond the individual SIB transaction. Beyond access to financial capital, investors have intellectual and often community capital that can be helpful in assessing whether to enter a deal.

In addition to improved relationships and understanding among investors, the success of social impact bond collaborations rests heavily on how government incentivizes investment and collaboration. For an in-depth exploration of the role of policy in incentivizing private investment from foundations, CDFIs, and investment firms, read the accompanying CAP issue brief, “Investing for Success: Policy Questions Raised by Social Investors,” which further explores findings from these social impact bond investor discussions.

Whether social impact bonds continue to grow, the exercise of exploring motivations among different types of actors can inform other investor collaborations. The groups of investors represented at the meetings—foundations, CDFIs, and investment firms—will all continue to provide crucial financial and intellectual capital to tackle social problems. The more they understand about one another and the more they connect within and beyond their own sectors, the better their chances of advancing social impact.

Kristina Costa was a Policy Analyst in economic policy at the Center for American Progress at the time of the drafting of this brief. Laura Tomasko is a network developer at the Council on Foundations.

The Center for American Progress would like to thank The Rockefeller Foundation and The California Endowment for their generous support of these meetings.