The Michigan state legislature last week rushed through a bill to institute a so-called “right-to-work” law, which will make it illegal for workers and employers to negotiate a contract requiring everyone who benefits from a union contract to pay their fair share of the costs of union representation. If Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder signs this legislation it will not only weaken unions, but also hurt workers, the middle class, and local economies in general.

The preponderance of economic evidence on the effect of labor unions on productivity and economic growth show that unions foster high-productivity, high-profit firms. Bottom line: Strong unions are good for jobs and “right-to-work” laws are not, as the evidence in this brief shows. Unions support a strong middle class and play a critical role in supporting our nation’s economic competitiveness by:

- Supporting high-productivity workplaces where information can flow from the bottom-up to improve business performance

- Supporting higher wages and benefits, not just for union members but across the board. High union density in a region tends to support higher wages across the region regardless of union representation, especially for workers at the lower end of the distribution

- Contributing to macroeconomic stability by giving certainty to consumption, saving, and investment in the economy

- Advocating for broader worker protections needed for families to make human-capital investments—strong public education, social safety nets, minimum wages, paid leave, and even civil rights and efficient regulation

A strong middle class, in turn, is what fuels competitive economies with high standards of living. Research on economic growth clearly shows the tried and true path to sustained economic growth is to build from the middle out—fostering an economy where growing economic opportunity and financial security build a burgeoning middle class. Moreover, a strong middle class is a key to all the building blocks that research says are the foundation of long-term economic growth:

- Education, skill development, and health of the work force

- Incentives for entrepreneurship

- Stable macroeconomic and financial balances

- Higher-quality governance in both public and private institutions

“Right-to-work” laws have failed to increase employment growth in the 22 states that have adopted such laws, and in states more recently adopting right-to-work, employment growth and business relocations have reversed their previous expanding trends. In other words, the economic evidence shows that unions and union membership, not “right-to-work” laws, are what are conducive to broad economic growth.

It is also important to note that “right-to-work” is a misnomer. While proponents frame this policy as being pro-workers’ rights, in fact, federal law already guarantees that no one can be forced to be a member of a union, or to pay any amount of dues or fees to a political or social cause they don’t support. Today in Michigan workers covered by a union contract can refuse union membership and pay a fee covering only the costs of workplace bargaining rather than the full cost of dues.

Michigan’s proposed legislation will allow some workers to receive a free ride, getting the advantages of a union contract—such as higher wages and benefits and protection against arbitrary punishment or discrimination—without paying any fee associated with negotiating on these matters. That’s because, by law, unions must represent all workers with the same due diligence regardless of whether they join the union or pay its dues or other fees. Additionally, a union contract must cover all workers, again regardless of their membership in or financial support for the union. As a result, right-to-work legislation weakens unions by making them provide services without being paid for them.

“Right-to-work” laws create fewer jobs and attract less business investment

There is really no economic evidence showing “right-to-work” laws leading to more jobs or better outcomes for workers. This is seen plainly in analysis looking at the impact of such laws in Oklahoma, the only other state to adopt a right-to-work law in the past 25 years prior to Indiana doing so in 2011 and Michigan’s current legislative move. In fact, economists Sylvia Allegretto and Gordon Lafer of the University of California, Berkeley and University of Oregon, respectively, show that since Oklahoma’s law passed in 2001, manufacturing employment and business relocations to the state actually reversed their “pre-right-to-work” increases and began to fall—and this at a time when Oklahoma’s extractive industry economies were booming. To the contrary, these researchers show that right-to-work laws have failed to increase employment growth in the 22 states that have adopted them.

As Henry Ford found a century ago, if workers don’t earn enough to spend on basics, the economy suffers. Paying workers a living wage not only boosts productivity, but it is also good for demand. As the middle class weakens or inequality rises, those not at the top don’t have as much to spend.

Unions strengthen the middle class

Unions strengthen businesses and the economically vital middle class by giving workers a voice in both the workplace and our democracy. Unions do this by pushing for fair wages and good benefits, and also by encouraging citizens to advocate for middle-class-friendly policies like a strong Social Security system and family-leave benefits.

In fact, according to a recent study conducted by the Center for American Progress Action Fund, strengthening unions is as important to the middle class as boosting college-graduation rates. Similarly, sociologists Bruce Western and Jake Rosenfeld of Harvard University and the University of Washington, respectively, have calculated that approximately one-third of the increase in male wage inequality from 1973 to 2007 was due to decreasing unionization—about the same amount they ascribed to the increasing payoff of a college education.

Not surprisingly, right-to-work laws have a negative impact on the middle class. The average worker—unionized or not— working in a right-to-work state earns approximately $1,500 less per year than a similar worker in a state without such a law. Workers in right-to-work states are also significantly less likely to receive employer-provided health insurance and pensions. If benefits coverage in non-right-to-work states were lowered to the levels of states with these laws, 2 million fewer workers would receive health insurance and 3.8 million fewer workers would receive pensions nationwide. And unions tend to especially make large income differences for communities of color in the United States.

All of the states with the lowest percentage of workers in unions—Mississippi, Arkansas, South Carolina, North Carolina, Georgia, Virginia, Tennessee, Texas, South Dakota, and Oklahoma—are right-to-work states and they all have a relatively weak middle class, with the share of total state income going to the middle 60 percent of the population below the national average.

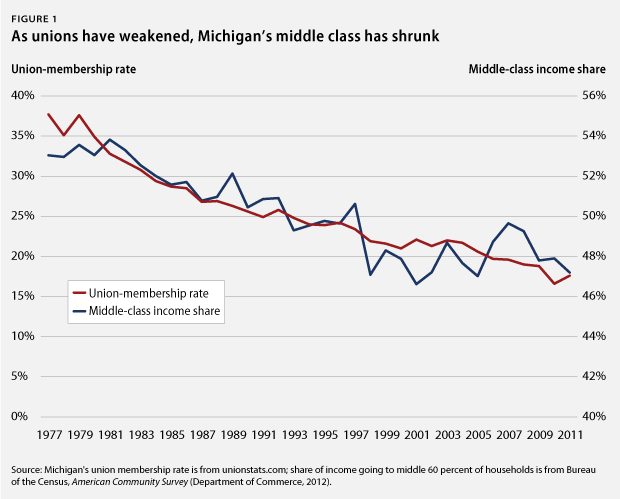

Over the past several decades, unions in Michigan have weakened and the middle class has been hollowed out—a trend that would significantly worsen if right-to-work became law. As we see in the data, as union membership has declined in the United States, so too has the share of income going to America’s middle class. (see Figure 1). In 2011 the middle class received the smallest share of the nation’s income since these data were first reported, according to U.S. Census Bureau, with the middle 60 percent of households receiving only 45.7 percent of the nation’s income that year, down from the historical peak of 53.2 percent in 1968. Since 1968 the share of households in unions has declined from nearly 30 percent to less than 12 percent today.

Despite claims that “right-to-work” would lead to stronger growth that would readily “trickle down” to workers at the lower end of the income distribution, it has not produced broadly shared gains. Moreover, the rising inequality due in part to policy efforts to restrain unions has contributed to economic instability and insecurity felt with more prominence throughout the U.S. economy. In the past two business cycle expansions, economic growth has failed to “trickle down” to those at the lower rungs of the income scale—instead poverty rose even as the economy grew. (see Figure 2)

Unions promote high-productivity workplaces

Economists Eileen Applebaum of Rutgers University, Jody Hoffer Gittell of Brandeis University, and Carrie Leana of University of Pittsburgh demonstrate the role that unions can play in creating high-productivity, high-performance workplaces. They find that workplace relationships based on mutual respect between employers and workers facilitate employee participation, bringing critical information to business practices from the bottom-up, higher productivity, and lower worker turnover that is costly to business.

Union workplaces and labor markets where union density is higher also show a higher tendency to promote important benefits such as paid sick leave. The research is conclusive that such policies—by preventing sicknesses from spreading in the workplace and promoting healthier, lower-stress employees—increases productivity, reduces worker turnover, and strengthens the loyalty of employees to the company. The lack of available-leave policy costs U.S. employers an estimated $160 billion per year in lost productivity.

Investment—in people’s human capital and in physical equipment, structures, and computer software—are the fundamental building blocks of economic and productivity growth. But business investment has slowed in the United States in recent years, even before the Great Recession, as unionization rates dwindled. Proponents of right-to-work laws claim their economic strategies are conducive to growth, however business investment did not race ahead as unionization declined.

To the contrary, nonresidential investment by nonfinancial businesses in the United States, adjusted for inflation and net of depreciation, slowed markedly and coincident with declining unionization over the last several decades. In the 2001-2007 business cycle business investment grew at an annual average rate of 4.4 percent, compared with an annual growth rate of more than 9 percent in the late 1970s business cycle expansion and an 8.1 percent growth in the 1960s expansion, when U.S. unions were stronger.

Unions pay middle-class wages and raise standards throughout the economy

Union workers earn significantly more on average than their nonunion counterparts. Unionization—even when controlling for other factors such as education, race, and gender—is associated with about a 15-percent increase in hourly wages in the typical state, according to a study by the Center for Economic and Policy Research that looked at the wage benefits of union membership in all 50 states. That means, all else being equal, workers who join a union will earn 15 percent more—or $2.50 more per hour—than their otherwise identical counterparts.

Numerous other studies have confirmed the positive effect of unions on workers’ wages and found similar effects for women and workers of color. And in specific job categories, such as carpentry, union workers enjoy middle-class wages while their nonunion counterparts struggle with poverty-level wages.

Moreover, unionized workers are more likely to receive benefits and their benefits are often of better quality than nonunion workers. Union membership is associated with about a 19-percentage point increase in the likelihood of having employer-provided health insurance and a 24-percentage point increase in the likelihood of having employer-sponsored retirement plans. And union employers often provide better health insurance benefits than nonunion employers, paying an 11 percent larger share of single-worker coverage and a 16 percent greater share for family coverage. Union employers also provide better pension benefits—spending 36 percent more on defined-pension benefits plans than nonunion employers.

Strong unions ensure workers are paid fair wages, receive the training they need to advance to the middle class, and are considered in the corporate decision-making processes. Unions also promote political participation among all Americans and help workers secure government policies that support the middle class, such as Social Security, family leave, and the minimum wage.

As a result, unions can also have a significant and positive effect on the wages and benefits of nonunion workers, both by setting standards that gradually become norms throughout industries and by serving as “threat” to nonunion employers in highly unionized industries. The so-called “threat” of unionization encourages employers in industries and markets where unions have a strong presence to pay their workers higher wages; these benefits then spread throughout the economy. In this way, unions help set the standard for all employers to follow.

A strong middle class—not “right-to-work”—is what fuels robust economic growth

Economists have shown that those at the top spend a smaller share of their income, which means that as inequality widens, there is less economic demand. Using longitudinal data, for example, Brookings Institution economist Karen E. Dynan, Dartmouth University economist Jonathan Skinner, and Columbia School of Business economist Stephen P. Zeldes find that savings rates range from less than 5 percent for individuals in the bottom 20 percent of the income distribution to more than 40 percent for those in the top 5 percent. Studying recent tax rebates, U.S. Census Bureau economist David S. Johnson, Northwestern University Kellogg School of Management economist Jonathan A. Parker, and Nicholas S. Souleles, economist at the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business, find that low-income households and households with few liquid assets spent a significantly greater share of their rebates than the typical household.

Whether the middle class has sufficient income to spend on basics is at the core of a body of economics research pointing to the interconnectedness of inequality and economic fragility. This body of this research stems from economists questioning whether the fact that the Great Depression and the Great Recession both followed decades of rising inequality was coincidence or whether there is a connection between inequality and economic instability. According to International Monetary Fund economists Andrew G. Berg and Jonathan D. Ostry, “countries with more equal income distributions tend to have significantly longer growth spells.” Inequality outweighed other factors in their analysis of the length of periods of positive economic growth across 174 countries. Income inequality was a stronger determinant of the quality of economic growth than many other commonly studied factors also included in their model, including external demand and price shocks, the initial income of the country (did it start out very poor or wealthy?), the institutional make-up of the country, its openness to trade, and its macroeconomic stability.

By supporting a strong middle class and less income inequality, unions can help economies avoid the instability associated with a hollowing out of the middle class. One line of argument from inequality to economic instability is that if higher inequality is associated with greater indebtedness, this increases economic fragility. University of Chicago Booth School of Business economist Raghuram Rajan points to rising inequality as a key fault line that led to the recent economic crisis precisely because it increased debt, mostly through mortgages. Similarly, International Monetary Fund economists Michael Kumhof and Romain Rancière have sought to understand the feedback between rising inequality and indebtedness in an illustrative model simulation and found:

When—as appears to have happened in the long run-up to both crises—the rich lend a large part of their added income to the poor and middle class, and when income inequality grows for several decades, then debt-to-income ratios increase sufficiently to raise the risk of a major crisis.

But we also know that a strong middle class creates the conditions for families to invest in children, for workers to invest in their human capital, and for firms to get the most out of their workers. While unions support productivity at a particular firm, a stronger middle class overall supports investments in education and good governance that grow the economy.

The middle class promotes efficient and honest delivery of government services, as well as forward-looking public investments. Because of the decline of the middle class, education spending is lower than it would be otherwise.

Indeed, four decades ago the United States ranked second among high-income countries in education spending as a share of gross domestic product—the broadest measure of a country’s income level—with only Canada outspending us, according to the World Bank. In 2008, the most recent year data are available, we ranked 11th—and Canada, whose middle class has also shrunk significantly, dropped to 16th, as countries with stronger middle classes like Sweden and New Zealand edged ahead.

In states across the country, a similar dynamic has played out as well. Since the Great Recession began, most states have cut education spending. Yet in those states with a stronger middle class, education spending has not been cut by nearly as much on average. Moreover, of the five states that cut education spending the most, the middle class in four is weaker than the national average. And of the five states that increased education spending the most, four had stronger middle classes than the average.

Indeed, a report by David Madland and Nick Bunker examining educational spending in all 50 states over the past two decades,found that a weaker middle class is associated with significantly lower levels of education spending, controlling for other factors that affect education spending such as state income levels, the percentage of minorities in a state, and the age distribution of the state.

Conclusion

Unions support a strong middle class and, increasingly, economists are finding evidence that a strong middle class is not only good for the workers and their families who directly benefit, but for the economy overall. We know that if workers cannot afford basics, ultimately the overall economy that suffers along with these individuals.

This so-called right-to-work legislation will make it harder for unions to do their job: improving wages and working conditions. That, in turn, will push our economy toward more weakening of the middle class, which will, in the end, lower our nation’s economic competitiveness.

Adam Hersh is an Economist at the Center for American Progress. Heather Boushey is a Senior Economist at the Center and David Madland is a Senior Fellow at the Center.