See also: 4 Charts that Show How Rising Income Inequality Increases Pessimism by Nick Bunker

This is a working paper.

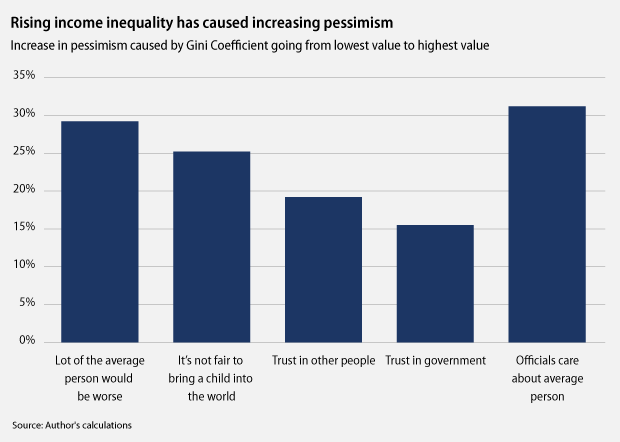

Rising inequality over the past decades led Americans to lose faith in some key aspects of the “American Dream” of a future that will inevitably be better than the past. We are less likely to believe that we have much in common with people who are not like ourselves and also that the people in power listen to or care what ordinary Americans think. Inequality makes people less likely to believe that what affects me affects you—and that ordinary people have the power to control the future or their political leaders.

I use data from the American National Election Studies surveys between the years 1966 and 2008, the General Social Survey (1972-2010), and the Pew Values Surveys (1987-2009) to examine the effects of rising inequality on indicators of optimism and pessimism, social cohesion, confidence in institutions, and personal expectations for the future. Key findings include:

- Americans have become more pessimistic and less trusting as inequality has increased in recent decades—especially as the income share of the top 20 percent rose while the share of the bottom 80 percent declined.

- Between 1973 and 1994 (the first and last times these questions were asked in a major national survey) the share of Americans who believed that the “lot of the average person is getting worse” rose from 56 percent to 69 percent —and all of this rise is attributable to increasing inequality.

- Between 1968 and 2006 the share of Americans who believed that “most people can be trusted” fell from 56 percent to 34 percent. Almost all of this drop is attributable to increasing inequality.

- In 1968, 63 percent of Americans believed that the government in Washington could be trusted to do the right thing, but only 14 percent agreed in 2008. Approximately a third of this drop can be attributed to increasing inequality.

- Between 1975 and 2010, the share of Americans who believe that “officials don’t care what people like me think” rose from 56 percent to 71 percent. This decline clearly tracks increasing inequality.

- Rising inequality leads people to become less optimistic about the future of our country and more skeptical of both their fellow citizens and their leaders. But it does not make them more pessimistic about their own prospects for success.

Such overarching pessimism—notwithstanding the finding that Americans remain individually optimistic about their individual futures—leads to less social cohesion and to greater polarization. This makes finding common ground on policy issues more difficult.

I find modest direct links between pessimism and the economic outcomes for which I could obtain data—owning homes, investing in stocks or starting a business. But there are probably greater effects for economic decisions that I could not test directly. And the effects of inequality on social and political cohesion may lead to negative economic outcomes. Polarization has already made it difficult for the leaders of the two political parties in the United States to reach accord on budgetary issues, which have clear consequences for the economy.

Policymakers should be concerned with the negative consequences of rising inequality and pessimism for the American dream. We are a society in which people have a fundamental belief that things are going to get better and that everyone will have a chance to succeed if she works hard enough. This dream—or promise, as most Americans interpret it—seems further away for many people.

Eric Uslaner is a professor of government and politics at the Department of Government and Politics, University of Maryland–College Park.

See also: