Introduction and summary

The United States and Mexico share more than one of the longest borders in the world; they have important economic, social, and political ties as well. The two countries share a complex history that is marked by both war and cooperation, competition and collaboration. As a result, issues that arise in one country directly affect the other.1 President Donald Trump, both as a candidate and as president, has cast a bright light on U.S.-Mexico relations and has been public with his views on the relationship. Among President Trump’s numerous assertions, his three main points of discussion have been: having a secure border;2 dismantling transnational organized crime;3 and assuring a stable and vibrant Mexico that “is good for the United States.”4

Having a secure U.S.-Mexican border that fosters joint security and stability is in the interest of the United States, as the binational relationship is fundamentally different from the United States’ relationship with any other country.5 Bilateral trade, social ties, and security cooperation are important issues—for both countries—that are highly influenced by the U.S.-Mexico relationship.

One of the biggest threats to security and stability—on both sides of the border—is the high level of violence in Mexico during the past decade. Addressing this issue requires multiple approaches—in particular, a focus on the uncontrolled flow of guns and money from the United States into Mexico that has contributed to increasing levels of violence. The United States is the biggest market for Mexican drug cartels, with drug trafficking generating around $64 billion per year—activity that goes hand in hand with the flood of guns entering Mexico.6 Between 2009 and 2014, nearly 70 percent of the firearms seized in Mexico came from the United States.7

Given the interconnectivity of the bilateral relationship, Mexico must implement unilateral strategies to address the various factors affecting its levels of violence. But there are also actions that the United States can implement to contribute to the reduction of violence in Mexico, which will benefit both countries. This report discusses two of these actions—strengthening Mexico’s rule of law and the reduction of gun trafficking into Mexico.

The importance of the U.S.-Mexico relationship

Today’s U.S.-Mexico trade dwarfs where the relationship stood fewer than 25 years ago. U.S. exports to Mexico increased from $41 billion in 1993 to more than $240 billion in 2014; imports from Mexico increased to $294.2 billion from $39.9 billion during the same time frame—a more than sevenfold increase.8 Approximately 40 percent of the value added in Mexican exports to the United States is of U.S. origin, and Mexico ranks second among U.S. export markets and is the third-leading supplier of U.S. imports. In 2015, total trade between the two countries amounted to $531.1 billion.9

The United States is Mexico’s largest source of foreign direct investment, or FDI, and Mexican FDI in the United States totaled more than $16 billion in 2015—the largest investment from Latin America and the Caribbean.10 Furthermore, Mexican companies have a strong presence in the United States and provide employment for many Americans. In 2014, Mexico-based, majority-owned affiliates of U.S. multinational enterprises employed 1.29 million people and had sales totaling $253.4 billion.11 For example, Grupo Bimbo, a major producer of bread, has built new plants in Pennsylvania and has generated more than 21,000 jobs throughout the United States.12 Likewise, Cemex, the second-largest cement company in the United States, provides more than 10,000 employment opportunities and is a key player in the U.S. housing market.13

Given the economic interconnectivity, North American supply chains, and favorable consumer prices, a prosperous and stable Mexico provides solid benefits for the United States. It strengthens competitiveness of U.S. firms, creates jobs in the United States, and generates savings for the average American family.14 However, Mexico’s economic competitiveness and stability are significantly linked to its levels of violence and insecurity. Until the early 1990s, U.S. and Mexican law enforcement officials viewed one another with deep suspicion, and cooperation was rare. In recent years, however, Mexico has become an essential homeland security ally—Mexican cooperation has been vital to the United States’ intelligence and law enforcement communities.

The Mérida Initiative, originally formulated by former U.S. President George W. Bush and former Mexican President Felipe Calderón, opened the door to a new era of security cooperation. This bilateral partnership agreement was launched in 2007 and deepened throughout former President Barack Obama’s eight years in office.15 For this effort, of the $2.6 billion that the U.S. Congress appropriated from fiscal year 2008 to fiscal year 2016, $1.6 billion has been delivered to Mexico and has focused on activities in four areas:16

- Disrupting organized crime—providing equipment to support the efforts of Mexican federal security forces engaged in anti-transnational crime organization efforts

- Institutionalizing the rule of law—police and judicial sector training, prison reform, forensic equipment and training, and crosscutting human rights programs

- Creating the 21st century border—facilitating the flow of people, commerce, and trade through U.S. ports of entry while securing the border against threats

- Building strong and resilient communities—addressing the underlying causes of crime and violence, promoting security and social development, and building communities that can withstand the pressures of crime and violence

Yet the deepest ties between the United States and Mexico are at the people-to-people level. There are 57 million Latinos in the United States, representing 18 percent of the overall U.S. population. Americans of Mexican heritage make up around two-thirds of U.S. Latinos—approximately 35.3 million.17 In addition, migrant networks, or hometown associations, have long allowed the Mexican diaspora to maintain engagement with relatives and their home communities—establishing effective cooperation networks between the United States and Mexico that have further strengthened the binational relationship.18 Equally as important are the more than 1 million Americans living in Mexico, constituting the largest U.S. expatriate community in the world.19

Violence in Mexico

The presence of organized crime has negatively affected Mexico over the past decade. Homicides increased significantly from 2007 to 2011, and after a slight decrease, they increased again from 2014 to 2016. A person is killed every 25 minutes in Mexico, and the majority of those deaths are related to organized crime.20 Although nearly all victims are Mexican, this wave of violence claimed the lives of 100 U.S. citizens in Mexico in 2014 and 103 in 2015.21 Other high-impact crimes such as kidnapping and extortion also increased considerably in Mexico during the past decade. As a highly effective criminal business model used to generate revenue, kidnappings rose 158 percent while extortions grew 68 percent from 2007 to 2016.22 A 2016 competitiveness report from the World Economic Forum shows that Mexico ranks particularly high among other nations on factors related to the presence of organized crime as well as the business costs of crime.23 This means that Mexico has serious issues with the presence of organized criminal groups as well as with the costs they impose.

This has brought considerable costs to Mexico’s population and to its private sector. Insecurity is the number one concern in 26 of the 32 Mexican states, and the monetary cost of crime for the population in 2015 was close to 12 billion U.S. dollars, or around 240 billion pesos.24 In 2015, business losses due to crime and expenses on preventative measures came in at 7 billion U.S. dollars, or 139 billion pesos.25 Violence and insecurity have affected foreign direct investment as well—investors and companies are risk-averse and do not like the instability, insecurity, and loss of revenues resulting from Mexican violence. As of April 2016, 25 states in Mexico had a decline in FDI directly related to insecurity, while only a few states—such as Querétaro, where crime is low—continued to have high levels of FDI.26

To have a more stable Mexico and a more prosperous region, the reduction of violence must be a priority for both Mexico and the United States. Addressing the problem requires a multifaceted approach that includes strengthening judicial procedures, fighting corruption, reforming the police forces, and further improvement in economic opportunities. While President Enrique Peña Nieto took an important step by implementing an anticorruption law in 2016, there is still much more that needs to be done. As Mexico’s 2018 presidential elections approach, high levels of violence must be at the center of the political debate, and candidates must include strategies to address the issue.

While Mexico implements unilateral strategies to reduce violence within its borders, there are actions that the United States can and should take to help build a secure border, dismantle organized crime, and ensure that Mexico is a stable and prosperous economic partner.

Steps the United States can take to strengthen the U.S.-Mexico relationship

Strengthening Mexico’s rule of law

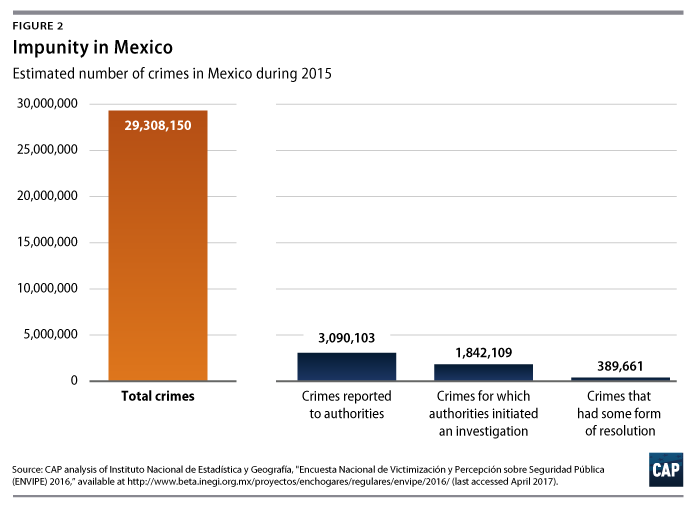

The high levels of violence in Mexico are directly associated with its levels of impunity when it comes to crime. During 2015, an estimated 90 percent of the close to 29 million crimes were not reported to authorities, and less than 2 percent had some form of resolution.27 As individuals perceive low costs to committing a crime, lawlessness tends to increase. Additionally, crime is clearly affecting Mexico’s economic competitiveness. Out of 138 countries, Mexico ranks 130th in reliability of police services.28 Therefore, one of the most important steps in addressing violence in Mexico is to improve its rule of law.

A crucial step to reduce impunity is to better implement the judicial reforms passed during 2008. These reforms were approved with the objective of replacing trial procedures at the federal and state levels and transitioning them from a closed-door process based on written statements to an adversarial trial with oral arguments.29 Fully implementing these reforms would also make trials more transparent, cheaper, and quicker, and the victims would have more participation as well as compensation.30 There would also be more physical space for court rooms; law enforcement officers would be able to participate in investigations; and, importantly, the accused would be presumed innocent until proven guilty.

2008 Mexican judicial reform: Main elements31

- Changes to criminal procedure through the introduction of new oral, adversarial procedures, alternative sentencing, and alternative dispute resolution mechanisms

- A greater emphasis on the rights of the accused—including the presumption of innocence, due process, and an adequate legal defense

- Modifications to police agencies and their role in criminal investigations

- Tougher measures for combating organized crime

Contributing to the implementation of these reforms has been one of the top priorities of the bilateral relationship. Through the second pillar of the Mérida Initiative, the United States has contributed approximately $111 million in efforts to reform Mexican police forces as well as the nation’s judicial system.32 In addition, the United States has provided equipment and training to implement codified standards, vet law enforcement, establish internal affairs units, and centralize personnel records.33 The United States has also provided training to federal, municipal, and local police forces on various tasks such as polygraphing and crime scene preservation.34 The United States helped the judicial reform by providing equipment to courtrooms and providing training to Mexican prosecutors, investigators, judges, and forensic experts in the new acquired accusatorial system.35

While there has been some success in the implementation of these reforms, there is still a long road ahead. The deadline for the full implementation of these reforms was June 2016, and currently, only four states out of the 32 are institutionally and resourcefully prepared to fully implement the accusatorial system.36 Half of the country started the new system with incomplete training and with a shortage of infrastructure.37 Additionally, a study by the Mexican think tank Centro de Investigación para el Desarrollo A.C., in collaboration with the U.S. Agency for International Development, found that at the current pace, the reforms would need 11 more years to be fully implemented.38

Instead of cutting back funding or shifting funds to pay for an infeasible and counterproductive border wall, the United States should continue efforts to support full implementation of these crucial reforms. Funding for the second pillar of the Mérida Initiative needs to continue to support these reforms through training and equipment, including forensic equipment, crime laboratories, nonintrusive inspection equipment, and computer software. In particular, this support could be targeted toward those states that are further behind on implementation, such as Baja California Sur, Oaxaca, Nayarit, Hidalgo, and Sonora.39

Additionally, assistance from the United States can contribute to complementary measures that reduce impunity and increase trust in the police. As noted by the Congressional Research Service, assistance to civil society and human rights organizations could strengthen the ability of these entities to monitor police forces.40 Additional support for civil society organizations will create indicators that track the performance of both the judicial system and police agencies—such as culture of lawfulness programs that seek to educate all sectors of Mexican society about the importance of upholding the rule of law.41 Such support is a positive step toward strengthening Mexico’s rule of law, ultimately increasing Mexico’s economic competitiveness and directly benefiting U.S. interests.

Prevent gun trafficking

Evidence suggests that the number of firearms used in crimes in Mexico has increased considerably since 2007. While Mexican security forces seized close to 45,000 firearms from 2000 to 2006, they seized almost four times as many during the following seven years.42 Because of its proximity to Mexico, its weak gun laws, and its increase in firearm production, the United States is the major supplier of illegal guns to Mexico.43 Data from the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, or ATF, demonstrates that between 2009 and 2014, 70 percent of firearms seized in Mexico and sent for tracing originated in the United States.44

Despite strict laws in Mexico that significantly limit firearm possession by private citizens, guns became the number one tool used to commit murders in Mexico after 2008, thanks in large part to the United States.45 And while gun murders represented 26 percent of the overall homicides from 1998 to 2006, they represented 55 percent of total homicides from 2007 to 2016.46 To place this figure in an international context, the average share of homicides carried out with a firearm among the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, or OECD, member countries is close to 21 percent.47

Similarly, 2011–2015 data from Mexico’s National Survey on Victimization suggest that a firearm was used in 65 percent of all crimes, compared with 45 percent in 2002.48

There are several gaps in current U.S. law and policy that contribute to and increase the illegal flow of guns across the southern border. Key among them is the loophole in the federal law that allows guns to be sold by private sellers at gun shows, online, or in any other venue without a background check and with no paperwork and no questions asked.49 The ATF has recognized that gun trafficking into Mexico is influenced by the availability of guns in secondary markets such as gun shows, flea markets, and private sales in the United States.50

Requiring background checks for all gun sales has proven effective in reducing illegal gun trafficking. U.S. states that have closed this loophole experience substantially lower rates of domestic gun trafficking to other states as well as lower rates of illegally trafficked guns into Mexico. For example, a 2014 study found that states without mandatory background checks exported guns to Mexico at rates 195 percent higher than states where background checks are mandatory on all private sales.51 In addition, the United States should expand the requirement that licensed gun dealers report to the ATF when an individual buys more than two long guns in a five-day period. Under federal law, gun dealers are required to report to the ATF when a person purchases more than two handguns in a five-day period, but this is not the case for long guns.

As multiple purchases can be an indicator of gun trafficking, the requirement to report multiple purchases by an individual buyer has been a crucial investigative tool. However, federal law does not require the reporting of multiple sales of long guns, including AR-15 and AK-47 rifles. In 2011, the Obama administration implemented a new regulation that extended this requirement to long guns but only applied it to the four southwestern border states. While 75 percent of U.S. firearms found in Mexico from 2009 to 2014 originated in Texas, Arizona, or California, close to 8,400 firearms originated in other states.52 To address this deadly gap, the U.S. government should extend the requirement to report multiple sales of long guns to cover sales in all 50 states. This would prevent gun trafficking schemes such as the one that occurred in Oregon in 2015, where two men were indicted, among other things, for allegedly buying more than $70,000 worth of high-caliber firearms with the intention of trafficking them.53 Some of these firearms included 0.50 caliber as well as AK-47 rifles, and some of them were later recovered in Mexico.54

Other policies to consider include increasing penalties for straw purchases, a preferred method for gun traffickers. A straw purchase occurs when a person knowingly purchases a firearm for someone who is prohibited by federal law from buying a gun.55 The Trump administration should also support legislation to ban or more strongly regulate the sale and possession of assault weapons such as AR-15 and AK-47 rifles, both of which are weapons of choice among criminal groups in Mexico.56 Finally, federal law enforcement can make more data available about guns that are seized in connection with crime in Mexico but originated in the United States to better inform policymaking and law enforcement efforts to reduce illegal gun trafficking across the border. While the ATF provides aggregated data about the number of firearms seized in Mexico that are traced back to the United States, it leaves out crucial information such as the type of firearm, the caliber, the maker, and the state and county where a gun was sold in the United States.

Efforts to reduce gun trafficking, however, cannot be implemented only at the federal level. With only seven states that have laws banning assault weapons and only 19 that have expanded background checks to private sales, there is substantial room for legislative efforts at the state level as well.57 States that have not yet done so should expand background checks to close the private sale loophole, and they should ban—or more strongly regulate—assault weapons and high-capacity magazines. Implementing these strong laws at the state level would not only reduce gun trafficking into Mexico but would also help reduce gun violence within the United States.58

There are nonlegislative actions that states should take as well. In an effort to complement the implementation of background checks, states should encourage licensed gun dealers to conduct voluntary background checks on behalf of private sellers and require background checks at gun shows that are held on public property.59 States should also evaluate their submission of records to the background check system and apply for federal funds to improve those records. Likewise, law enforcement should investigate and prosecute individuals who have attempted to purchase a firearm but failed to pass a background check. Besides being an indication of a potential safety risk, failed background checks are an indication of gun trafficking. Finally, states should also form a gun crime investigative unit and create illegal-gun tip lines.60 The latter has proven to be an effective tool to prevent gun trafficking in cities such as Miami and New York City by allowing individuals to make anonymous calls without fear for their safety.61

While many factors have strengthened criminal groups and contributed to violence in Mexico, easy access to firearms has played a major role in fueling homicides and other crimes. As most firearms originate in the United States, there is a shared responsibility in reducing the levels of violence experienced by our southern neighbor. In this regard, the Trump administration, as well as state authorities, should implement strategies and actions that not only reduce gun violence in the United States but also reduce gun trafficking into Mexico.

Conclusion

President Trump promised to fix perceived insecurity at the U.S.-Mexico border throughout his campaign. Although levels of insecurity in U.S. border communities are actually among the lowest in the nation, the United States can bolster border security and stability by helping tackle high levels of violence that have arisen in Mexico during the past decade.62 Mexico needs to implement unilateral strategies to address the various factors affecting its levels of violence domestically; however, the United States can implement actions—at home and abroad—that help reduce violence in Mexico to the benefit of both countries. The United States can help strengthen Mexico’s rule of law and reduce gun trafficking across its southern border, which would increase Mexico’s economic competitiveness and ultimately benefit U.S. interests. A stable and vibrant Mexico is good for the United States.

About the authors

Eugenio Weigend Vargas is the Senior Policy Analyst for the Guns and Crime Policy team at the Center for American Progress. His work has focused on firearm regulations in the United States and the illegal flow of weapons into Mexico. He has a Ph.D. from Tecnologico de Monterrey and a master’s degree in public affairs from Brown University.

Joel Martinez is the Mexico Research Associate on the National Security and International Policy team at the Center.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Chelsea Parsons, Dan Restrepo, and Michael Werz for their contributions to this report.