Introduction and summary

Dr. Arjun is a kidney specialist from India who operates multiple dialysis units in Mississippi. Some of these units are located in rural areas as far as 50 miles away from his home in Jackson, Mississippi.1 While Dr. Arjun received offers from bigger cities, he chose to serve in a rural area since his ultimate goal was to practice in a place where his services were most needed. Mississippi has some of the highest rates of poverty and obesity in the country and thus has a high incidence of kidney disease, especially among people of color. Once Dr. Arjun received an opportunity to interact with patients and witness the need in the region, he decided to settle there. He feels deeply proud of the service he is providing, and his patients—most of whom are African American—are equally grateful. They often tell him that they hope he never leaves the area, a concern that is all too real for rural residents who have long struggled to find stable, accessible, and quality health care.

Of the numerous issues facing rural communities—from grocery store closures to school closures and consolidations2—lack of adequate health care services perhaps most tangibly affects the lives of residents. Notably, the worsening shortage of physicians in rural communities has made it exceedingly difficult for residents to find care. As of January 2019, rural and partially rural areas in the United States accounted for 66 percent of the total primary care Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs)—a designation for health care provider shortages—whereas nonrural areas had only 34 percent of all designations.3 A geographic area is designated as an HPSA if, among other issues, it has fewer providers relative to its population, it serves a higher percentage of people who live below 100 percent of the federal poverty level, and it takes a long time for residents to get to the nearest source of care.4 To remove these designations, rural and partially rural areas would need 6,607 more primary care physicians. Rural residents are also facing increasing numbers of hospital closures, as well as issues such as limited transportation, lack of health care coverage or insufficient insurance coverage, and poor health literacy.5

All these challenges translate to diminished access to quality health care for rural residents. Often, these residents do not visit their doctors to get preventive care. And even if they do visit a physician, the wait to get an appointment with a doctor may be long, they may be unable to find the specialists they need, or the doctors that are available may be stretched thin or overworked. There are numerous stories that illustrate the plight of rural residents and their struggle to get adequate care. For example, in Webster County, Georgia, there are no doctors available; one pregnant woman’s first trip to the doctor was for her delivery. Another resident and her son walked about 8 miles back from an appointment in Columbus before a motorist offered a ride, and others simply avoided visiting the doctor altogether.6 Unfortunately, these health care access challenges are likely to get worse in the coming decades because many rural communities have aging populations whose health care needs and use of services will be different—and greater—than those of other age groups.7 For this reason, it is more important than ever to address this crisis now.

Nationally, physicians who are foreign trained or international medical graduates (IMGs)—most of whom are non-U.S. citizens8—make up almost one-quarter of active physicians.9 In some specialties, such as geriatric medicine and nephrology, IMGs make up approximately 50 percent of active physicians.10 Many foreign-trained physicians who are neither U.S. citizens nor permanent residents—referred to as “immigrant doctors” in this report—have long been providing essential health care services in these rural communities, adding to available care options.11

This report highlights physician shortages in rural communities, explores some of the main pathways through which immigrant doctors end up practicing there, and provides broad federal and state policy recommendations to better incorporate immigrant doctors into the effort to tackle the rural health care crisis. Through interviews with immigrant doctors practicing in rural communities, this report shines a light on the barriers they face, in terms of both immigration and licensing.

As the report outlines, immigrant doctors must go through multiple hurdles before they can serve an area. These challenges range from complex and restrictive immigration laws to national and state medical licensing processes and their stringent requirements. And rural communities, which are struggling to attract any doctors—regardless of where they were born or trained—face additional challenges in recruiting and retaining immigrant doctors. Federal laws do allow these underserved communities to benefit from immigrant doctors, but the current path for immigrant doctors to practice anywhere is paved with a patchwork of federal immigration policies and mismatched state licensing regulations that do not truly work in anyone’s best interests—neither those of the physicians nor those of the underserved rural communities. Below are some major drawbacks of the system in place today:

- Many immigrant doctors use J-1 exchange visas to complete their residencies in the United States, with the expectation that they will return to their home countries and spend at least an aggregate of two years before they can apply for certain visas. However, if they want to stay in the United States and practice, they need to apply for a waiver of this requirement, called the Conrad 30 program, which is only available if they commit to practice in a federally designated Health Professional Shortage Area, Medically Underserved Area, or Medically Underserved Population for at least three years.12 While this waiver program helps both rural communities and immigrant doctors, it needs to be reauthorized every two years by Congress and only gives states 30 waivers, regardless of their size or need.

- Immigrant doctors can also apply for H-1B visas to work in the United States. H-1Bs are dual-intent visas that make immigrant professionals eligible to apply for permanent legal residence, known as a green card, if their employer agrees to file it for them. This visa is extremely difficult to get since it has an annual cap and is often oversubscribed.

- The wait times to get a green card, using any of the employment-based categories, are ridiculously long for applicants from certain large countries, such as India and China. Due to per-country limits placed on green cards and a limit on the total number available each year, there are massive backlogs, and certain applicants may have to wait for decades before one becomes available.

- Each state has its own set of laws and policies to license physicians for state practice. As a result, immigrant doctors must navigate the complicated process of getting their state license on top of making sure they maintain their immigration status. This means that they have to overcome numerous barriers in order to meet their full potential.

There are, however, ways to improve and streamline policies and processes to ensure that communities that are significantly underserved by physicians can recruit immigrant doctors to ease some of the health care inequities and improve health care access. These include legislative fixes to the J-1 visa program, reforms to the H-1B visa category, modifications to the per-country limit, and state-level efforts to remove medical licensing barriers. Through a strategic and multipronged approach at different levels of government, the United States would be able to harness the talents of immigrant doctors to help minimize physician shortages in rural communities.

Physician shortages disproportionately affect rural communities

Due to challenges on multiple fronts, the demand for better health care services is high in rural communities. For one, residents in rural areas are older; their median age is 51, compared with 45 for residents in nonrural areas.13 In addition, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that higher percentages of rural residents die from preventable causes than do urban residents, which could be the result of various factors, ranging from high rates of cigarette smoking, high blood pressure, and poverty to lack of health insurance and limited access to health care.14 Furthermore, while the opioid epidemic has hit nationwide, there are slightly higher rates of recorded drug overdose deaths in nonmetropolitan areas than in metropolitan areas; compared with other areas, nonmetropolitan areas also had higher rates of natural and semisynthetic opioid-related drug overdose death rates.15

Set against this backdrop of increasing demand for quality health care, the United States is going through a worsening physician shortage. The 2019 Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) report projects that by 2032, the United States will have shortages of from 46,900 to 121,900 physicians overall and from 21,100 to 55,200 primary care physicians, as well as a shortage in nonprimary care specialists.16 Currently, about 14,472 more primary care physicians are needed to offset the undersupply in designated shortage areas. One of the main reasons for this projected physician shortage is the expected shift in demographics, as the growing population of older adults will demand more health care services. The same AAMC study projects that by 2032, there will be approximately 50 percent growth in the population of those ages 65 and older, compared with only 3.5 percent growth for those ages 18 or younger.17

On the supply side, even though medical schools have been training more doctors since 2002, a 1997 Medicare cap on funding for graduate medical education resulted in an undersupply of residency training slots available for prospective physicians, “creating a bottleneck.”18 Data show that in the past four decades, more medical graduates have applied for residencies than there have been slots available.19

This physician shortage is felt even more acutely in rural communities. In these areas, there are only 13.1 physicians and surgeons per every 10,000 residents, compared with 31.2 physicians in urban areas.20 While physician-to-population ratio is an imperfect method of measuring access to care, in the absence of more granular data, it can help show whether there are enough doctors working in an area to adequately serve residents. A 2018 survey from The Medicus Firm of more than 2,000 medical professionals shows that physicians overwhelmingly prefer urban areas to rural areas, likely due to greater career opportunities.21 Only 8 percent of those surveyed said that they are currently practicing in a small town or rural community.22 Moreover, only 6 percent of those surveyed reported wanting to live and work in these communities, compared with more than 60 percent saying they would prefer to practice in a metropolitan or suburban area. To make matters worse, rural areas have been increasingly plagued by hospital closures; the North Carolina Rural Health Research Program estimates that more than 100 rural hospitals have closed since 2010.23 Many of these closures were due to financial distress driven in large part by a declining rural population.24

Combined, these challenges exacerbate the woes of rural residents, further decreasing their access to quality and timely health care services. In 2017, NPR detailed one powerful example in which a resident in a rural Arizona town changed her primary care doctor four times because her doctors were no longer practicing there.25 She was forced to travel more than 60 miles round trip to another town just to see a doctor. It is hard for rural hospitals to recruit doctors because salaries in urban hospitals are more competitive. Moreover, shifting immigration policies have made it harder to recruit immigrant doctors; there are even instances where immigrant doctors who are already serving rural areas are forced to move away in pursuit of positions that would allow them better opportunities to receive a permanent residency, regardless of whether they want to stay.

Case study: Forced to decide between family and practice in a beloved rural community

Dr. Deepti Smitha Kurra worked in Marshalltown, Iowa, as a general practitioner for six years.26 She took a job there because it was a federally designated underserved area that fulfilled her J-1 visa waiver requirement and because she found a practice she liked. When she moved to Marshalltown, it had 16 physicians and three experienced advanced practitioners. Her practice was fully booked, with 11 physicians supported by experienced nurse practitioners. Yet by the time she left, only four physicians remained in the entire town, with a few more physician assistants, and Dr. Kurra had a hard time recruiting new physicians to take her place.

Dr. Kurra developed a deep bond with her patients, who were older, often had multiple health problems, and in many cases lacked proper transportation or family support to take them to their appointments. She remarked that if it hadn’t been for her, they would have had to travel 40 minutes just to see a primary care physician. The shortage of physicians became so severe that Dr. Kurra had to constantly work overtime to meet the demand. She also stretched her skills as a general practitioner because otherwise, her patients would have to go to other towns to see specialists, which was difficult for them.

Eventually, Dr. Kurra had to make a difficult decision to leave her patients, the place she loved, and the house she bought. Although she and her husband had applied for green cards years ago—through the National Interest Waiver27 and an employer, respectively—they were still waiting for visas to become available. Her husband, an aerospace engineer, could not find a job in Marshalltown that would sponsor him, so he ended up working for a company in Cedar Rapids. While his job there was initially flexible, after his company was acquired by another company, he needed to travel to Cedar Rapids daily, which became very difficult for their young family. Therefore, Dr. Kurra chose to keep her family together and move to Cedar Rapids, where both she and her husband could find a job. Yet she is convinced that if her family had a stable immigration situation, she would have never left her patients in Marshalltown.

Immigration pathways doctors take to practice medicine in the United States, and their barriers

International medical graduates who are neither U.S. citizens28 nor legal permanent residents have two main options to train or practice in the United States:

- The J-1 visa, under the Exchange Visitor Program, is a temporary nonimmigrant visa category that allows immigrant professionals to gain knowledge and skills that will be valuable in their home countries.29 Immigrant doctors generally use J-1 visas to complete their graduate medical education in the United States.

- The H-1B visa is a temporary visa that allows employers to recruit foreign workers in specialty occupations.30

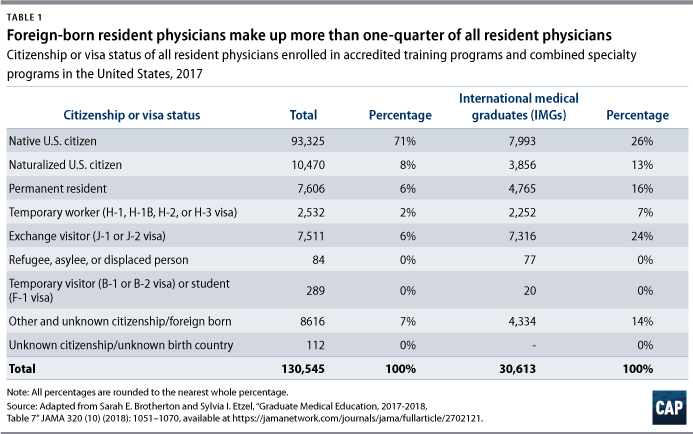

Of the total 130,545 resident physicians in the United States in 2017, nearly 30 percent, or 37,220, were not U.S. born.31 Moreover, about half of those who were not U.S. born were not naturalized or did not have permanent residency and were therefore on some type of visa. (see Table 1)

Additionally, many immigrant doctors use a National Interest Waiver (NIW), which allows physicians and other highly skilled professionals to petition for employment-based permanent residence provided they can prove that it is in the national interest to allow them to work permanently in the United States.32 Among other requirements, physicians under an NIW must practice full time for at least five years in an area federally designated to have a shortage of health care professionals or at a health care facility under the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.33

J-1 visa

Immigrant doctors who wish to train in the United States under J-1 visas must be sponsored by the Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG), which is authorized by the U.S. Department of State to sponsor medical graduates for clinical trainings and research.34 Other requirements for eligibility include passing the first and second levels of the U.S. Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE), having an offer from an accredited medical or training program, and holding an ECFMG certificate.35 The visa can be renewed for a maximum of seven years to allow the medical graduate to complete clinical training. J-1 visa holders are eligible to have their spouse, as well as their unmarried children under age 21, classified as dependents under J-2 visa.36 According to data collected by the Department of State, among the 2,738 J-1 visas granted to physicians in 2018, Canadians made up 25 percent of the total, Indians made up 18 percent, and Pakistanis made up 9 percent.37

To secure the required medical residency in the United States, IMGs must compete with U.S. medical graduates for a limited number of available slots. It is not guaranteed that they will be matched with a residency; in fact, immigrant doctors are matched at a lower rate than those who graduated from U.S. medical schools. Data on residency matches show that while 93.9 percent of those who graduated from U.S. medical colleges were matched in 2019, only 58.6 percent of foreign-trained non-U.S. citizens were matched.38 This means that there were about 2,841 non-U.S. citizens IMGs who passed exams but were unable to secure a residency slot and thus unable to fulfill licensing requirements. There are various reasons why medical graduates who passed the same standard USMLE have different matching rates. A Minnesota task force found that residency programs often prefer recent graduates; however, many immigrant doctors have already spent years completing residencies in their home countries following graduate school and therefore do not fit that bill. Residency programs may also prefer graduates with clinical experience in the United States, which is almost impossible for someone who studied and trained abroad to have.39

After physicians complete their residencies under a J-1 visa, Section 212(e) of the Immigration and Nationality Act requires both them and their J-2 dependents to return to their home country for an aggregate of at least two years before they are eligible to adjust their status to certain other visa categories, such as H-1B.40 But Section 220 of the Immigration and Nationality Technical Corrections Act allows interested government agencies (IGAs) to request a waiver of this two-year home residence requirement as long as certain conditions are met. One of the main conditions is that IMGs commit to serve full time in a Health Professional Shortage Area, Medically Underserved Area (MUA), or Medically Underserved Population (MUP) for at least three years.41 Operating under this law, the U.S. Department of Agriculture became the largest agency to sponsor primary care physicians from abroad, sponsoring approximately 3,000 waivers until its program abruptly ended in 2002.42 Several federal government agencies have acted as IGAs, including the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the Appalachian Regional Commission, and the Delta Regional Authority.43

At the state level, the Conrad 30 Waiver Program, established in 1994, allows states to sponsor a limited number of waivers to J-1 physicians wishing to practice in a certain state. The program is administered through a designated state public health department, with each state offering up to 30 waivers per year.44 The J-1 visa waiver application, submitted by the employer and the applicant, must be approved by the U.S. Department of State.45 Ultimately, U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) reserves the right to grant the waiver and approves the request for the physician to receive an H-1B visa under the waiver, which paves the path for the physician to apply for a green card through the employment-based (EB) category. However, there are serious backlogs in green card availability, especially for individuals from large countries such as India and China.

H-1B visa

Another visa category that immigrant doctors may use for residencies and to work in the United States is the H-1B visa for specialty occupations. Unlike J-1 visas, H-1Bs are dual-intent visas that allow their holders to apply for permanent residence without requiring them to go back to their home country first.46 The dependents of H-1B holders—spouses and unmarried children under age 21—are eligible to receive visas under H-4 nonimmigrant classification.47 Although H-1Bs are attractive, they are harder to acquire because they are so highly sought after among professionals and have an annual cap, as well as other requirements. The demand has been so high that from 2014 to 2018, the annual cap for H-1B visas was reached within the first five business days that they were made available.48 In cases where the annual cap is met, which has become the norm, USCIS conducts a random lottery to decide on which petitions to process.49 Many residencies may be exempt from this annual cap because they meet one of the following criteria: “institution of higher education or its affiliated or related nonprofit entities or a nonprofit research organization, or a government research organization.”50 But once those H-1B doctors finish their residencies and have to transfer to an employer, who may be nonexempt from the cap, they have to go through the H-1B lottery. Moreover, in contrast to J-1 visas, which are sponsored by the ECFMG, physicians seeking H-1Bs must find a sponsoring institution willing to apply on their behalf. The applicant must also clear all three required levels of the USMLE to apply for an H-1B, compared with just two exams for J-1 visas. Additionally, before an H-1B is approved, applicants must meet state licensing requirements, which vary significantly by state for residents and fellows.51 It is particularly challenging for immigrant doctors to meet all these requirements when they are at the beginning stages of their residencies. Furthermore, an H-1B is only a three-year visa that can be extended once to a maximum of six years. This limit may not give doctors enough time to finish their residencies and fellowships and start to practice.52

Under the H-1B visa category, individuals are eligible to apply for a green card if their employer is willing to petition for them, but there are major hurdles for those of certain nationalities. Each independent country, regardless of its population size, cannot be issued more than 7 percent of the total yearly green cards available worldwide for family- and employment-based categories.53 In 2017, approximately 140,000 green cards were issued to applicants and their dependents in the United States in the employment-based categories.54 In these categories, the number of visas are also subject to numerical limits based on preference levels—ranked from one to five. Employment-based first preference (EB-1) is for “priority workers” with extraordinary abilities, who receive 28.6 percent of the 140,000 green cards available worldwide as well as any unused visas from the fourth and fifth preference levels. Second preference (EB-2) is for “members of the professions holding advanced degrees or aliens of exceptional ability,” who also receive 28.6 percent of green cards available, as well as any unused visas from the first preference.55 There is an extremely high bar for individuals applying for the EB-1 category. USCIS requires these applicants to provide multiple pieces of documentation verifying their “extraordinary ability” in the sciences, arts, and other fields or evidence of a one-time achievement such as a Pulitzer, an Oscar, or an Olympic medal.56

Together, these policies have created massive backlogs for people from large countries with many applicants who have applied for green cards through their U.S. employers. According to the data released by USCIS, in all employment-based categories, there are 306,601 Indian applicants and 67,031 Chinese applicants in the United States who have a priority date57 on or after May 2018 and are waiting for a visa to become available.58 If the number of dependents is included, this figure increases from 373,632 applicants to 423,392 applicants for India and China combined. If it was not for the per-country caps imposed on the visas, all these applications may have been processed and the applicants could have already received their visas. A recent Cato Institute analysis showed that the average wait periods for people from India, China, the Philippines, and Mexico increased from 1991 to 2018 for all categories, employment and family based.59 The analysis also estimated that the time spent waiting for Indian applicants in the two employment-based preference levels, EB-2 and EB-3, increased from 0 years in 2004 to 9.9 years in 2018. It predicted that Indian applicants who applied under these two preference levels in 2018 may have a waiting period of half a century.60 For example, Dr. Arjun applied for his green card in 2011 through his employer. He has now been waiting for more than eight years and has no idea how much longer it will take, since USCIS is only processing people who have a priority date of April 2009 or earlier.

Another consequence of long green card wait times is that children who are on their parents’ visas have few options after graduating from high school. Since most of these children have grown up and received an education in the United States, it makes no sense to place barriers on their career and educational aspirations. When they apply to college, they will not have access to federal scholarships and federal student aid.61 Moreover, if they cannot find an alternative, some children risk losing their status and being forced to go back to their country of origin once they turn 21 and are no longer eligible for an H-4 visa.

Dr. Arjun worries about his daughter’s future if he does not get a permanent residency in time. She came with him to the United States as a 1-year-old and is one of the top students in her high school class. Yet when she applies for college, she will most likely be subjected to all the restrictions that come with being an international student.

Meeting national and state licensing requirements

For immigrant doctors, earning a license to practice in the United States is a complicated, lengthy process that they must go through at the same time as maintaining their immigration status and making sure they have enough earnings and funds available to take care of themselves and their families. Currently, each state has varying requirements for granting international medical graduates a license to practice.62 On top of passing the three levels of the USMLE and receiving certifications through the ECFMG, which also verifies their credentials, states directly check IMGs’ credentials.63 Moreover, the majority of states require immigrant doctors to complete at least three years of residencies in the United States or Canada, regardless of whether they have previously completed a residency in another country.64 These multiple processes are in place to ensure that immigrant doctors receive qualifications and training that are comparable to those of physicians who graduated from a U.S. or Canadian medical school. While standardized licensing processes help protect public safety, there is significant variation in requirements among states, with some being far more restrictive than others.

The ways in which states implement their Conrad 30 Waiver Program differ widely. Each year, states can apply for 30 waivers to recruit immigrant doctors who have completed their residencies under J-1 visas. Most or all of the 30 waivers are awarded to physicians who agree to work in federally underserved areas. Many states, such as Iowa and Maine, also have up to 10 flexible waivers that allow physicians to work in a facility that is not in a federally designated underserved area but still serves patients who live in underserved areas. Other states, such as Tennessee and Virginia, have five flexible waivers. Meanwhile, in states such as Alabama and Arizona, there are no flexible waivers. Furthermore, there are differences in how states define primary care and what subspecialties are accepted for these waivers.65 It can be beneficial for states to have more control and flexibility over where to direct their pool of physician applicants and what kind of physicians they need to attract. However, to ensure that the program is meeting states’ specific needs, policymakers must tackle the larger issue of states only being able to offer a limited number of waivers.

Ways rural communities can recruit and retain immigrant doctors

There are several ways in which rural communities can recruit and retain immigrant doctors and build lasting relationships with physicians who settle in their localities. Research shows that many immigrant doctors practicing in rural communities end up staying in those areas even after they have met their three-year requirement under the J-1 waiver. For example, among 406 immigrant doctors in Iowa with a J-1 waiver under the Conrad 30 program, 92 percent completed their three-year requirement, and 68 percent remained at the original site for four or more years.66 Yet other states, such as Wisconsin, had trouble retaining J-1 waiver physicians, with retention declining after two years.67 The Wisconsin study, which surveyed leaders at institutions participating in the Conrad 30 program, found the retention issue to be correlated with an inability to integrate these physicians into the community due to a lack of services that met their religious and cultural needs.

Legislative changes at the federal level are needed to simplify and strengthen the various pathways through which physicians can practice in these high-need areas. Beyond these policies, states must also take action to reduce barriers to licensing for immigrant doctors to practice and settle in their states. The following policy recommendations are just a starting point to breaking down barriers for immigrant doctors to serve in rural areas and improving retention.

Congress can help boost the number of immigrant doctors serving in rural communities

Although immigrant doctors generally use J-1 or H-1B visas to train and practice in the United States, neither category is flexible enough to easily accommodate years of required residency trainings, allow physicians to practice after completing their training, and provide immigrant doctors with an easy pathway to permanently settle in the United States. If the United States wants to effectively tap into this talent to tackle the shortage of physicians in rural communities, more needs to be done.

Make the Conrad 30 Waiver Program permanent

The Conrad 30 Waiver Program is one avenue through which immigrant doctors under the J-1 visa end up practicing in rural areas after completing their residencies.68 The program waives the two-year home residency requirement under the condition that the J-1 physicians practice in a federally designated medically underserved area; as a result, physicians who wish to stay and practice in the United States can do so, and underserved communities in high need of physicians can get them. Currently, however, Congress extends the program inconsistently, from a few months to as long as a few years, making it an unreliable avenue through which to recruit physicians.69 While the program has been reauthorized without issue several times in the past few years, this may not always be the case, especially in the current anti-immigrant environment.70 A bipartisan Senate bill introduced in 2015 called the Conrad State 30 and Physician Access Act proposed to make this program permanent.71 In 2019, a bipartisan bill called the Conrad State 30 and Physician Access Reauthorization Act was introduced in the Senate to reauthorize the program, extending it to September 2021 and adding several other provisions to improve it.72 A House version of the same bill was also introduced in 2019 by a bipartisan group of representatives.73 For example, this bill would improve the visa application process, allow spouses of doctors to work, and enhance worker protections for doctors.74

Increase the number of J-1 visa waivers provided through the Conrad 30 program based on states’ needs

States offer only 30 J-1 visa waivers per year under the Conrad 30 program, regardless of the demand for physicians or the size of the state. About half of states generally use their allotted 30 slots every year, while the other half do not use them all.75 A 2018 study of the program in Iowa showed that in most years from 1996 to 2016, Iowa filled almost all of its allotted slots.76 On the other hand, a 2012 evaluation of the Delaware Conrad 30 program found that from 2000 to 2011, the 30 slots available to the state were never fully filled.77 However, as physician shortages have worsened, the use of J-1 visas has increased.78 Employers who previously thought that the J-1 process was cumbersome and expensive or that communities would not accept a foreign doctor are now more willing to consider it. Especially after the 2008 recession, employers found the cost of applying for an H-1B visa prohibitive and started opting for J-1 visas instead. This meant that there were more J-1 physicians who were searching for positions and applying for the Conrad 30 program.

The limit in the number of waivers for states is both arbitrary and inflexible; it is unrelated to the size of states’ populations, shortages of physicians and specialists, or state demand. The federal government should either remove the restriction entirely or increase the number of slots available to make it easier for states to offer enough waivers to meet demand. The bipartisan Senate bill passed in 2013—S. 744—gradually increased the number of waivers for states that used most of their allotted waivers, with certain limits.79 Increasing the number of slots for states that can demonstrate need will help them recruit enough physicians to supply underserved and rural areas. With more options, it would also be easier for physicians under J-1 waivers to find positions that are good fits for them.

Remove J-1 visa waiver program restrictions that prevent doctors from changing employers

Currently, during the three years of their contract, immigrant doctors under the J-1 visa waiver program are not able to change their employer unless there is a qualifying “extenuating circumstance,”80 such as the closure of a facility or hardship to the physician. This is extremely restrictive for physicians who would like to move away from a site due to reasons that do not qualify as extenuating circumstances. These doctors may find that their place of work is not conducive to growth, that they do not get along with their colleagues, that they dislike how the facilities are run, or that they simply dislike the work culture. Yet under U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services rules, such work issues are not reason enough to allow an immigrant doctor to change employers.

Case study: Immigrant doctors’ inability to change employers is limiting their potential

Dr. Chivukula, one of the few geriatric psychiatrists in West Virginia, practiced in Fairmont for about eight years.81 He served elderly patients who suffered from dementia, memory issues, depression, and other problems. While he built strong relationships with his patients, he was not satisfied with his position; during his time in Fairmont, his employers never talked about career growth or salary changes. But due to the restrictions tied to his J-1 visa waiver, he could not change his employer, move to a facility close by that also served an underserved area, or grow his practice. But even within the limits of a J-1 waiver, he managed to serve more people by getting involved in another project at a university in the area, where he ran a memory clinic.

Dr. Chivukula believes that “all physicians are leaders” but that because of immigration requirements, some are unable to advance in their fields and serve their patients as comprehensively as they would like. Allowing physicians such as Dr. Chivukula to change their employers would provide them some relief and freedom to seek out other, more fulfilling positions.

Other doctors who are waiting for green cards under H-1B visas share these sentiments. For example, a nephrologist in Mississippi relayed that because his status was tied to his employer, it prevented him from starting his own practice and doing more for his patients.82

Strategically reform the allocation of H-1B visas to tackle labor market shortages in high-need areas, raise wages, and end the random lottery system

In recent years, there have been more petitions filed for H-1B visas than there have been visas available. Moreover, these visas have been allocated through a random lottery system—which is not a particularly strategic way to allot any visa. The H-1B allocation process needs to be reformed in a way that is advantageous for both the country and its workers. For example, it should give preference to petitions from employers in areas and occupations experiencing high shortages. This would make it easier for rural health care facilities that have trouble finding doctors to recruit immigrant doctors under H-1B visas. Furthermore, bills have been introduced in Congress to reform the program in a way that would protect wages for all workers. In 2017, Rep. Zoe Lofgren (D-CA) introduced legislation designed to recruit highly skilled and highly paid workers who would complement the U.S. workforce.83 Among other things, Rep. Lofgren’s legislation would have increased the prevailing wage required to recruit H-1B workers and eliminated the lowest pay category.84 Another bipartisan bill introduced by Sens. Dick Durbin (D-IL) and Chuck Grassley (R-IA) would have ended the lottery system and given preference to foreign students educated in the United States.85 Bills such as this that propose ranking H-1B visas may end up hampering the ability of immigrant doctors to access them; policymakers should be wary of this and put forward legislation that prioritizes these doctors.

Clear immigrant visa backlogs and remove per-country caps on employment-based green cards for occupations facing high shortages

Waiting for a green card is a long and arduous process, especially for immigrants from large countries such as India and China. Fortunately, a number of bills have been introduced in both the House and Senate to remove per-country limits or at least attempt to improve the application process for certain doctors. For example, S. 948 proposes that doctors who get a National Interest Waiver (NIW) and commit to practice in an underserved community should be exempt from the green card quotas.86 This would give them an incentive to stay in a rural community long after their J-1 visa has ended—and provide an added benefit to the community. Currently, incentives to apply for a NIW and spend five years in a rural area instead of a suburban hospital are diminished because of the long wait times regardless of whether people receive an H-1B and practice anywhere or get a NIW and commit to stay in a rural underserved area.

The Fairness for High-Skilled Immigrants Act of 2019—formerly known as S. 392—is the latest version of a bill that proposes to eliminate per-country limits for employment-based immigrants.87 However, some advocates lament that this bill would pit small countries against large countries, since USCIS would have to work through massive backlogs before advancing any new applications—likely from both large and small countries.88 Therefore, this process would increase wait times for many applicants from smaller countries in order to benefit applicants from a few larger ones.89

To avoid increasing the current wait times for applicants from smaller countries, the existing backlogs in high-shortage occupations need to be cleared and per-country caps need to be eliminated. Moreover, the new system should give preference to applicants on the basis of their filing date or on a first-come, first-served basis.90 To achieve this without affecting current applications and creating new backlogs, the worldwide limit for green cards either should not apply while processing the backlogs or a separate bucket of new visas should be made available until there are no more backlogs. Such a change in policy would provide relief to thousands of individuals and families who have been waiting for their time to come, but it would not delay current applications. Furthermore, to free up more visas, if an employer is interested in sponsoring an immigrant worker’s green card, that immigrant’s dependents should not be counted against the caps in the employment-based category.91 In fact, S. 744 explicitly stated that dependents should not be counted against the quota.92

However, it will be difficult to truly prevent future backlogs without increasing the total number of green cards available each fiscal year.

Case study: How one immigrant doctor helped battle the opioid crisis in West Virginia

Many immigrant doctors whose immigration status is in limbo believe that if they had green cards, they would be able to do more with their expertise, getting involved in more projects and serving more people.93 The story of Dr. Reema, a child psychiatrist in West Virginia, shows what happens when physicians have stable immigration status and can work toward bettering themselves and their communities.94 She was educated and trained in India. Ten years ago, while still on a J-1 waiver, she began noticing the impacts of substance abuse and the opioid crisis in very young children. As a child psychiatrist, she often saw preschoolers with severe behavioral problems. They often were exposed to opiates before birth and had chaotic living situations early in their childhood. There were not many services available in the community to help such families.

At that time, Dr. Reema remained on her H-1B visa while waiting for a visa to become available under the EB-2 category. However, since an H-1B visa holder is only able to work for the sponsoring organization, she could not contract with another organization and was limited to the job description provided by her employer. Changing jobs would have meant finding an employer willing to sponsor her H-1B visa and take over her green card processing. She had limited options in the community where she lived, and moving meant uprooting her family. She ultimately decided to join a university that was willing to work with her and her attorney so that there would not be a lapse in status.

The position at the university allowed her to get involved in more targeted work related to the opioid crisis. She, along with a group of doctors and community leaders, decided to focus on the unique needs of children and babies who have been affected by substance abuse and the opioid crisis. Over time, this group started to partner with different community groups—including day care centers, pediatric units, OB-GYNs, the city government, and churches—to educate them about substance abuse and involve them in a continuum of programs.

The work group applied for grants and used those funds to provide services for young families and children affected by substance abuse. In one of the programs, for example, social workers and substance abuse coaches are paired with pregnant women or mothers of young children to provide them with the support, guidance, and services they need to navigate their lives. This support system helps mothers and prospective mothers find transportation; apply for the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC); and secure resources available in the community. In another new program, the work group has partnered with a facility to provide day care services for babies who had withdrawal symptoms at birth because their mothers had substance abuse problems; these unique needs demand specialized care. The work group is involved in many other similar programs to serve disadvantaged children and young families affected by the recent drug abuse crises.

While Dr. Reema was getting involved in all this great work, she was also working though her green card process. The EB-2 category has a lengthy wait time, and with her H-1B clock running out at nine years, she also applied on her own in the EB-1 category, which has a relatively shorter wait time since it is for individuals with exceptional abilities. After spending more than $10,000 on an attorney, she was eventually able to secure a green card through this pathway.

Dr. Reema’s story illustrates not only the circuitous path physicians have to take to achieve a stable immigration situation, but it also shows the potential of physicians who are free to get involved in projects and activities and simply do more to serve their communities.

States and localities can be at the forefront of attracting and retaining immigrant doctors

Federal solutions can greatly and permanently improve the ways immigrant doctors can help reduce health care shortages and increase quality of care in rural areas, but states and localities can also do a lot more to remove barriers to attract and retain immigrant doctors. Getting rid of unnecessary red tape and restrictions; equalizing policies; and, at the end of the day, treating physicians as people who are looking for advancement will help states retain physicians and ultimately improve health care access.

Establish a task force to study states’ licensing requirements and processes and implement solutions to remove barriers for immigrant doctors to re-enter their profession

While governed by the same federal statutory requirements, each state’s laws and policies uniquely shape immigrant doctors’ pathway to getting licensed. Some state governments have formed task forces to identify roadblocks that prevent immigrant doctors from re-entering their profession. For example, Minnesota, under 2014 Minnesota Session Laws, established a task force of diverse groups that released a report identifying barriers for immigrant doctors and crafted a set of policy recommendations.95 The task force identified four significant barriers in the state: limited residency spots, residencies preferring recent medical graduates, a failure to recognize experience in other countries, and the costs of testing and other requirements for medical graduates to get licensed. To address these barriers to increasing health care access in rural and underserved areas, Minnesota created a program called the International Medical Graduates Assistance Program.96

Similarly, in 2014, under the direction of executive order, Massachusetts’ Governor’s Advisory Council on Refugees and Immigrants (GAC) put together a task force comprised of health care workers, community organizations, government agencies, and others that published a series of recommendations to improve and simplify licensing of medical professionals in Massachusetts.97 Currently, the Massachusetts state legislature is working on passing a bill that calls for a special commission to make recommendations about how to license immigrant doctors, with an aim “to expand and improve access to medical services in rural and underserved areas.”98 In January 2019, Virginia also introduced a bill requesting that the Department of Health Professions conduct a study on utilizing foreign-trained physicians to address the needs of rural and underserved areas.99

Other states should follow the lead of Minnesota and Massachusetts and methodically study their own health care needs to determine how immigrant doctors are contributing—and how they could contribute more if significant roadblocks were removed.

Streamline residency requirements and simplify application processes for J-1 visa waivers

All doctors, regardless of where they are trained, must pass the same national U.S. Medical Licensing Examination before they can practice in the United States. And medical graduates are also required to go through residencies. For immigrant doctors, clinical trainings received abroad do not fulfill this requirement, no matter how many years they have spent in residencies after receiving their medical degrees. For example, Dr. Reema, who received her medical degree in psychiatry and completed three years of residency in India, had to spend three more years in residency training in Michigan after completing required exams and getting certifications in the United States.100

One possible solution to this issue is to recognize training from other countries for licensing and immigration purposes as long as countries have medical education systems that are similar in quality to that of the United States.101 While ensuring that foreign-trained doctors have the same level of experience as U.S. medical graduates is a reasonable policy to protect public safety, differences in years of residency required across states are arbitrary. Moreover, the standards are different between graduates of foreign medical schools and graduates of medical schools in the United States.102 Almost always, the number of years required for immigrant doctors to be licensed in different states is more than it is for U.S.-educated doctors. One 2014 study that researched state licensing requirements from 1973 to 2010 found that states that have restricted licensing receive fewer foreign-trained doctors.103 The study concluded that half the states could solve their physician shortage issue over five years if they made licensure requirements the same for U.S.-educated and foreign-trained physicians.

The differences among states are not just limited to residency requirements, however, as there are varying requirements for recruitment, contract terms, acceptance of subspecialties, application fees, and more.104 States that want to attract immigrant doctors should examine how their recruitment standards and procedures can be improved so that communities can easily recruit the doctors they need while also adhering to statutory requirements.

Conclusion

Thousands of immigrant residents live and work in rural communities, contributing to the revitalization of these communities and providing essential services. In many rural places, immigrants offset chronic population decline and other side effects of the loss of local residents to greater opportunities and facilities in urban areas.105 Immigrants have been vital to the revival of many rural communities; they are business owners who strengthen local economies, factory workers and farmers who bolster the labor force, and—perhaps most importantly—health care workers who provide much-needed services to all residents.106 Immigrants have also stabilized local populations and even contributed to population growth in many rural places, thus helping communities avoid population decline.

Immigrant doctors can be a bigger part of the solution to health care inequities and physician shortages in rural and underserved communities.107 Unfortunately, however, their contributions and advancement are severely limited by federal immigration policies that are not flexible enough to accommodate their training and licensing processes. Immigrant physicians, especially from large countries, are struggling to get permanent residency, placing their immigration status in limbo and hampering their ability to serve the communities they now call home. Moreover, convoluted licensure policies at the state level put an unnecessary burden on immigrant doctors looking for residencies and jobs.

Many times, the connections that doctors develop with their patients and the relationships that they build with their communities may be enough reason for them to stay. Yet some are still making the difficult decision to move away because they do not see their immigration situation improving. In spite of these hardships, immigrant doctors are still grateful to be serving rural areas. Dr. Arjun, thinking back on all the fellowships and board certificates that he has received in the United States, remarks, “I owe this country; they welcomed me here … instead of taking, there is some giving back.” It is time that the United States rewards the valuable services immigrant doctors provide and the contributions they make to some of the most overlooked parts of the country. Commonsense federal and state policy changes could greatly change the status quo for immigrant doctors, allowing them to use their talent strategically to tackle some of the overwhelming problems that rural communities face.

About the author

Silva Mathema is a senior policy analyst of Immigration Policy at the Center for American Progress. Her current research focuses on U.S. immigration and refugee policies, as well as the role of immigrants in rural America. Previously, she worked as a research associate for the Poverty & Race Research Action Council, where she studied the intersections between race and ethnicity issues and policies regarding affordable housing and education. Mathema earned her Ph.D. in public policy from the University of North Carolina at Charlotte, where her dissertation focused on the impact of a federal immigration enforcement program on the integration of Hispanic immigrants in Charlotte-Mecklenburg, North Carolina. She graduated magna cum laude from Salem College with a Bachelor of Arts in economics. She is originally from Kathmandu, Nepal.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to the doctors who gave their invaluable time to explain their issues and shine a light on the contributions they make to rural communities. She is also thankful to Gregory H. Siskind from Siskind Susser PC for reviewing the draft of this report and clearing up questions related to immigration law; to Jeffrey Gross from WES Global Talent Bridge for providing valuable insights into state policies; and to David Bier from the Cato Institute for his helpful feedback.

She also thanks Tom Jawetz, Philip E. Wolgin, and Emily Gee of the Center for American Progress for their inputs and support, and intern Lora Adams for her help in researching state policies.