Renowned French economist Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century thoroughly documents how those at the very top of the income distribution are pulling away from the rest of us. In the United States, wealth inequality has skyrocketed to levels not seen since the 1920s, with the top 0.01 percent of Americans owning more than 10 percent of all national wealth. As sobering as that is, Piketty argues that economic inequality will grow even worse over time, based on his contention that the rate of return on capital will exceed the overall growth rate for the economy. If capital, or wealth, grows faster than the economy, then the owners of that capital and their heirs will amass an even larger share of total national wealth over time. To reverse this trend, Piketty advocates a global wealth tax.

This issue brief puts aside the question of whether new policies, such as a global wealth tax, should be enacted to reduce economic inequality. Instead, it explores two existing policies that actually subsidize wealth inequality. First, reduced tax rates on capital gains and dividends increase the after-tax rate of return on wealth, which makes it more likely that the rate of return on capital will exceed the overall economic growth rate. Second, capital gains are never subject to the income tax at all if the investor dies, which subsidizes wealth concentration within a family dynasty.

These two subsidies will cost the U.S. federal government about $2 trillion over the next 10 years, almost all of which will go to the wealthiest Americans. Past Congresses have repealed both of these subsidies at different points in time, though they were later revived by subsequent legislation. Recently, tax reform proposals from both sides of the political spectrum have once again advocated scaling back or eliminating these subsidies.

Even if new policy interventions such as a global wealth tax are not politically or administratively feasible at this time, the federal government could still decisively respond to growing wealth inequality by simply scaling back the tax subsidies that help the rich get richer.

Low tax rates for capital gains and dividends

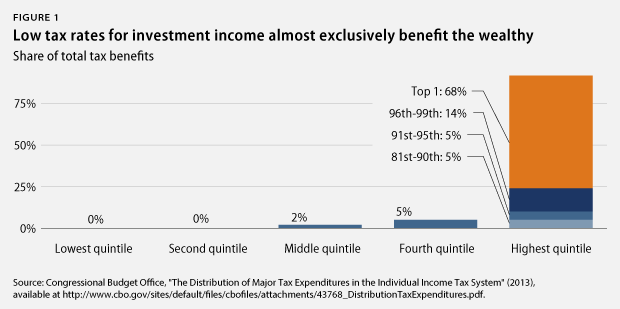

Capital gains and dividends are taxed at lower rates than other sources of income. Labor income, such as wages and salaries, is taxed at rates of up to 39.6 percent and also subject to payroll taxes. Capital gains and dividends, which are investment income, are taxed at a top rate of 23.8 percent, which includes the 3.8 percent surtax on investment income imposed by the Affordable Care Act, or ACA. Those lower rates are a subsidy for investment income. Subsidies in the tax code are known as tax expenditures, and the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office, or CBO, estimates that the tax expenditure for low rates on capital gains and dividends will cost the federal government $1.34 trillion in revenue over the next 10 years. Taxpayers with incomes in the top 1 percent will get 68 percent of that money, while the bottom 80 percent will receive only 7 percent.

Reducing tax rates for investment income has delivered enormous windfalls to the wealthiest Americans and exacerbated economic inequality. A study by Thomas L. Hungerford of the Economic Policy Institute finds that, “By far, the largest contributor to increasing income inequality (regardless of income inequality measure) was changes in income from capital gains and dividends.” By taxing capital gains and dividends at a lower rate than other income, the federal government is making it more likely that the rate of return on capital will exceed the economic growth rate—the key driver of Piketty’s theory of rising future economic inequality.

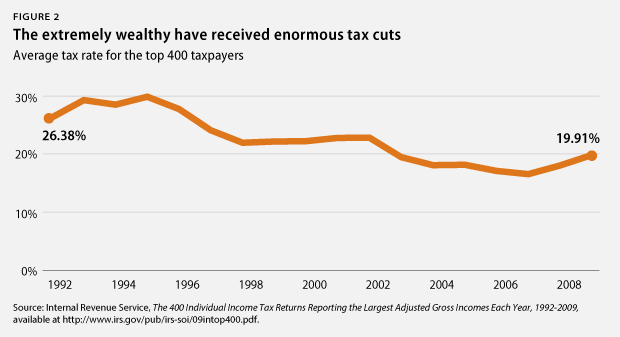

The effects of preferential tax rates for capital gains and dividends are most apparent when looking at the richest of the rich using Internal Revenue Service, or IRS, data on the country’s top 400 taxpayers. These taxpayers represent the top 0.0003 percent of all 140 million individual income tax returns filed in 2009, the last year for which data are available. Amazingly, this tiny group claimed a full 12 percent of all capital gains that benefit from reduced tax rates.

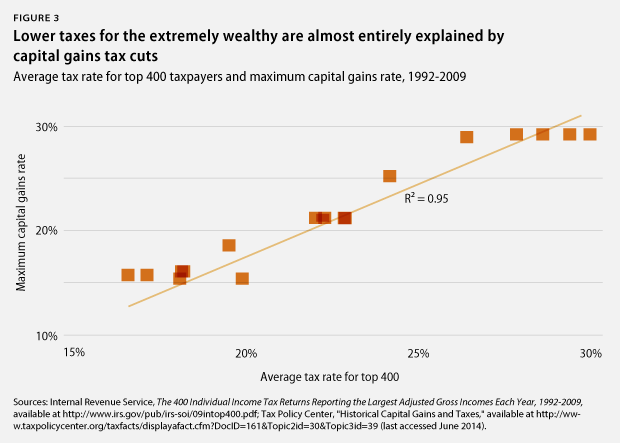

The average tax rate for these extremely wealthy taxpayers has fallen dramatically in recent decades. The top 400 taxpayers faced an average tax rate of 26.38 percent in 1992, which fell to 19.91 percent by 2009. This tax cut for the extremely wealthy can be explained almost entirely by reductions in the capital gains rate. The correlation between these two drops is nearly perfect, with 95 percent of the change in the average tax rate for the top 400 taxpayers explained by capital gains tax cuts. This trend has likely reversed in recent years to some extent, since the top capital gains tax rate has increased from 15 percent in 2009 to 23.8 percent today.

Presumably, federal lawmakers did not enact preferential rates for capital gains and dividends for the sole purpose of subsidizing wealth inequality. Defenders of this tax break offer several justifications for it. Some argue that investment tax breaks reduce double taxation, since profits are taxed at both the corporate level and at the individual level when distributed to shareholders as capital gains or dividends. But under this logic, almost everything could be called double taxation. For example, workers pay income taxes when they earn a paycheck and then pay sales taxes on that income when they spend it. Martin A. Sullivan of the nonprofit Tax Analysts, a provider of tax news, analyzes this question in an article titled “Are Capital Gains Double Taxed?” He concludes that “framing the debate in terms of double versus single taxation gets us nowhere.”

Some also defend low rates for capital gains on the grounds that some of the gain is due to inflation rather than a real accumulation of wealth for the investor. This concern is not addressed directly, however, by a discounted tax rate. The discounted tax rate may overcompensate or undercompensate for the effects of inflation, depending on the actual inflation rate over the holding period of the investment. As an alternative to a discounted tax rate, proposals have existed for decades to index capital gains taxes to inflation so that only the real portion of the gain is taxable. However, this would be inconsistent with other areas of tax policy in which inflation is not taken into account, such as the tax treatment of interest and deductions for the depreciation of business investment. Additionally, the burden of paying taxes on inflationary gains is at least partially offset by allowing investors to defer capital gains taxes until they sell the asset.

Additionally, opponents of high capital gains rates raise concerns about the potential lock-in effect, in which investors are reluctant to sell assets and incur capital gains taxes. Studies have found evidence of the lock-in effect in the short term, with changes in capital gains taxes associated with substantial increases or decreases in asset sales, but this effect is much smaller in the long term. While some argue that capital gains tax cuts actually pay for themselves by reducing the lock-in effect and increasing the volume of taxable asset sales, a report from the nonpartisan Congressional Research Service finds that “the bulk of the evidence suggests that reducing the capital gains tax rate reduces tax revenues.” It should be noted that the lock-in effect is not an issue for dividend taxes, since investors do not have an option to defer dividend payments or the resulting tax obligation.

The most important question for low tax rates on capital gains and dividends is whether they help the economy, but the evidence supporting this tax subsidy is not compelling. Supporters argue that this tax expenditure encourages savings and investment, which in turn boosts the economy. Economists generally agree that increased investment is good for the economy but disagree on whether tax preferences for capital income achieve this result, especially in today’s global marketplace where domestic savings can finance foreign investments and vice versa. Some economists believe a tax system that yields optimal economic growth would completely exempt investment income from taxation. Economists Peter Diamond and Emmanuel Saez, however, find that this conclusion relies on unrealistic assumptions about human behavior. For example, economic models supporting tax-free investment income assume that everyone can borrow unlimited amounts of money with which to invest and then make rational long-term savings decisions, neither of which is true in real life.

Reasonable economists can disagree about the theoretical benefits of low capital gains taxes, but the historical record is clear. There is no correlation between low capital gains tax rates and higher economic growth. To be fair, correlation is not the same as causation. It is possible that low capital gains tax rates have helped the economy, but the effect is so small that it has been eclipsed by other factors.

Investment income has not always been taxed at preferential rates. Dividends were generally taxed as ordinary income until the 2003 tax cuts enacted under former President George W. Bush. Capital gains have a longer history of preferential rates but were also taxed at the same rate as ordinary income from 1988 to 1990 as a result of the Tax Reform Act of 1986, which was signed into law by then-President Ronald Reagan.

Several recent tax reform proposals advocate reducing or repealing the subsidy provided by reduced rates on investment income. The bipartisan deficit reduction commission chaired by Erskine Bowles, a businessman and former White House chief of staff for President Bill Clinton, and former Sen. Alan Simpson (R-WY) called for eliminating preferential tax rates for capital gains and dividends while also reducing the top income tax rate to 28 percent. Another bipartisan commission led by former Senate Budget Committee Chairman Pete Domenici (R-NM) and Alice Rivlin, formerly President Clinton’s White House budget director, also proposed taxing capital gains and dividends as ordinary income, with an exemption for the first $1,000 of capital gains and a lower top income tax rate of 27 percent.

House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Dave Camp (R-MI) also proposes a slight increase in capital gains and dividend taxes in his Tax Reform Act of 2014. Rep. Camp’s bill would lower the top income tax rate to 35 percent while allowing investors to exclude 40 percent of their capital gains and dividends from taxable income, with the remaining 60 percent taxed at ordinary rates. A 35 percent tax on 60 percent of capital gains and dividends results in an effective tax rate of 21 percent, or 24.8 percent with the ACA surtax. A bipartisan tax reform bill from Sens. Ron Wyden (D-OR) and Dan Coats (R-IN) takes a similar approach, exempting 35 percent of capital gains and dividends and taxing the rest at ordinary rates of up to 35 percent, for an effective tax rate of 26.55 percent with the ACA surtax.

A comprehensive tax reform proposal from the Center for American Progress would tax dividends as ordinary income, returning to the framework used for 90 years until 2003. Capital gains would be taxed at a top rate of 28 percent, including the ACA surtax, which is the same tax rate that President Reagan enacted in the Tax Reform Act of 1986.

‘Step-up in basis’ for capital gains

Piketty warns of “patrimonial capitalism,” in which inheritances drive economic outcomes more than talent or hard work. A provision of the tax code known as “step-up in basis” is a direct subsidy for inherited wealth.

When an asset is sold, the capital gain is the sales price minus the seller’s basis in the asset, with the basis usually equaling the price that the seller originally paid. For inherited property, however, the basis is generally the fair market value of the asset on the date the previous owner of the asset died. Calculating an heir’s basis in an asset using its more recent value when the previous owner died, instead of its original cost, is called a step-up in basis.

As an example, imagine that Jill purchases a share of stock in 1980 for $10. Jill still owns the stock when she dies in 2003, and the stock is now worth $50. Jill’s son Jack inherits the stock and sells it in 2007 for $55. Even though the stock has gained $45 from its initial cost of $10, Jack only has to pay capital gains taxes on the $5 gain that occurred after Jill passed away. The other $40 in capital gains is never subject to income taxes, since Jack benefited from a step-up in basis. Notice that step-up in basis worsens any lock-in effect caused by capital gains taxes, since it gives investors a powerful incentive to hold onto assets until they die.

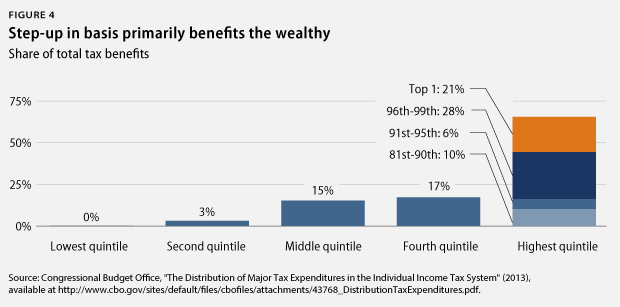

CBO estimates that the step-up in basis rule will reduce federal revenues by $644 billion over 10 years, with 21 percent of that subsidy going to the top 1 percent of income earners.

Step-up in basis is a particularly valuable subsidy for the wealthiest estates. A study published by the Federal Reserve estimates that unrealized capital gains comprise 55 percent of the total value of estates worth more than $100 million. That means more than half of the wealth accumulated within the richest estates was never subject to income taxes.

Some wealthy and sophisticated individuals combine step-up in basis with other rules called “like-kind exchanges” to avoid incurring taxable capital gains. Businesses and investors can avoid capital gains taxes when they sell certain kinds of assets, if they use the proceeds from the sale to buy a similar type of asset. Real estate is the most common type of asset used to benefit from like-kind exchange rules, but other investment property, such as art, can also qualify for this favorable tax treatment. Rep. Camp’s Tax Reform Act of 2014 repeals like-kind exchange rules, and his Republican staff note, “With multiple exchanges, gains essentially may be deferred for decades, and ultimately escape taxation entirely if the property’s basis is stepped up to its fair market value upon the death of the owner.”

Congress repealed step-up in basis in the Tax Reform Act of 1976, replacing it with “carryover basis.” Carryover basis means that the heir’s basis is the same as the decedent’s basis, so the taxable capital gain on an asset is not affected by inheritance. However, Congress postponed this change in 1978 and then repealed it retroactively in 1980. According to the Joint Committee on Taxation, Congress repealed the carryover basis rules due to concerns that they increased the cost and complexity of administering estates. Estates faced challenges determining the decedent’s basis in cases where records were unavailable to establish the original price paid by the decedent for the asset.

The Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001, or EGTRRA, attempted to revive carryover basis rules while also phasing out estate taxes. Under this law, carryover basis rules applied in 2010, the same year the law eliminated estate taxes. The year 2010 ended up being a highly unusual year, with the Tax Relief, Unemployment Insurance Reauthorization, and Job Creation Act of 2010 allowing estates to choose between two sets of rules. Estates could elect the EGTRRA tax treatment of no estate tax but carryover basis or the new law that revived the estate tax and step-up in basis. Once again, administrative complexity was a primary concern with the carryover basis rules for 2010, with then-Senate Finance Committee Chairman Max Baucus (D-MT) warning of “massive recordkeeping confusion.”

While recordkeeping concerns with carryover basis have twice led Congress to revive step-up in basis for estates, carryover basis rules are actually routinely applied by the tax code when dealing with gifts from a living donor. Under Section 1015 of the Internal Revenue Code, the recipient of a gifted asset generally assumes the same basis in that asset as the donor held. Section 1015 even anticipates situations where the recipient of the gift does not know the donor’s original basis, which is the recordkeeping concern used to justify step-up in basis for estates. In these cases, the IRS inquires with the donor or anyone else who might have information on the original basis of the gifted asset. If no one can provide this information, the IRS determines the basis by estimating what the fair market value of the asset was when the donor originally acquired it, using whatever information is available.

To be sure, there are differences between estates and gifts that make a carryover basis regime more difficult to apply in the case of estates. The previous owners are deceased when assets are inherited from estates, so the IRS cannot ask them about their original basis as they do for gifts. Additionally, donors of gifts can strategically select assets for gifting in which they have a high—and easily determined—basis, a practice that financial advisors encourage since the higher basis leaves the recipient with a smaller capital gains tax burden. Of course, decedents are not around to make such choices for their estates.

Both the Bowles-Simpson and Domenici-Rivlin commissions recommended repealing step-up in basis. There may be legitimate administrative concerns with carryover basis, but policymakers should think hard about whether there are more-efficient ways than step-up in basis to address those concerns. Indeed, $644 billion over 10 years is a high price to pay to ease paperwork burdens, especially when that money primarily subsidizes concentrations of inherited wealth.

Fiscal impact of subsidizing wealth inequality

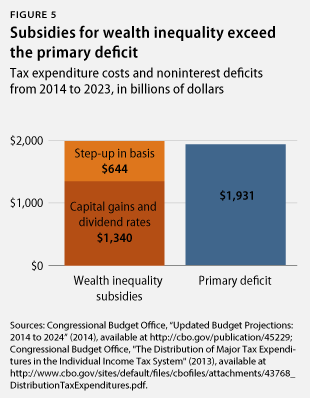

The federal budget outlook would be substantially different if not for step-up in basis and reduced rates on capital gains and dividends. While detailed annual cost estimates for tax expenditures are only available for a five-year window, CBO recently published estimates of the total 10-year cost for major tax expenditures. Those figures were used earlier for the cost estimates in this report, and together they total $1.984 trillion from 2014 to 2023.

CBO estimates that primary deficits—meaning deficits that do not include interest costs for the national debt—will total $1.931 trillion from 2014 to 2023. If not for these two tax expenditures that subsidize wealth inequality, federal revenues would be more than enough to pay for all federal programs over the next 10 years, meaning the federal budget would have a small primary surplus. To be clear, the federal government would still run modest overall deficits once interest costs are included. Primary deficits or surpluses matter because they measure whether current taxes can pay for current programs. If the budget has a primary surplus, then any residual deficit is entirely due to interest payments, which reflect earlier decisions that grew the national debt, not current policies.

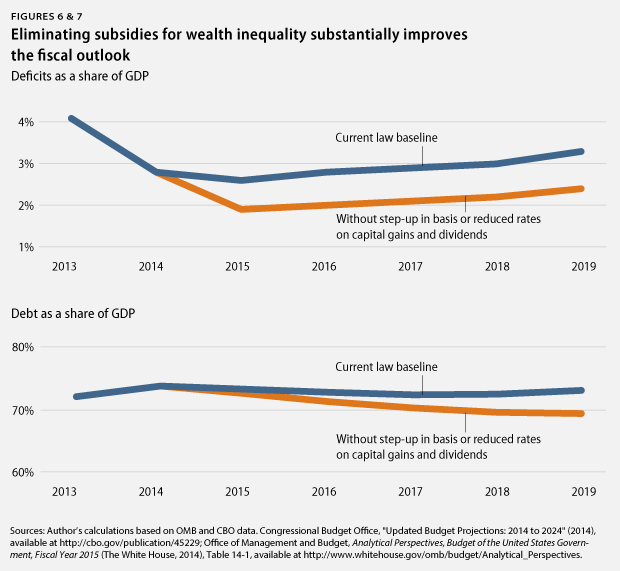

The federal budget outlook has already improved substantially relative to a few years ago. In fact, CBO projects that in each of the next three years, deficits will be so low that the economy will grow faster than the debt, meaning that the national debt will fall as a share of gross domestic product, or GDP.

Eliminating subsidies for wealth inequality would further improve the budget outlook. Under current law, CBO projects that debt will start to increase as a share of GDP starting in 2018. If step-up in basis and low tax rates for capital gains and dividends are repealed, however, debt would remain on a downward path through the end of the most recent five-year budget window for which detailed tax expenditure estimates are available.

It is likely that repealing low rates for capital gains and dividends and step-up in basis at the same time would actually have an even larger fiscal impact, since the two subsidies interact with each other. CBO estimates individual tax expenditures separately, meaning the effect of repealing two tax expenditures at the same time is not included in its analysis. The Office of Management and Budget, or OMB, also leaves interactions out of its analysis. Repealing step-up in basis broadens the base of capital gains subject to taxation, but OMB and CBO assume this broader base is taxed at the reduced rates that currently apply to capital gains. If capital gains tax rates were higher, the fiscal impact of repealing step-up in basis would be larger than OMB and CBO estimate.

American wealth is concentrated within the richest families at levels not seen since the 1920s, and the American people should ask whether our government should incur roughly $2 trillion in deficits over the next 10 years for two policies that subsidize wealth inequality. To start answering that question, the public benefits from these subsidies should be weighed against their fiscal cost, as all spending programs and tax expenditures should be. But even if these policies do have some merit, perhaps there are other ways to spend $2 trillion that deliver equal or greater public benefits without subsidizing inequality to such a dramatic extent.

Harry Stein is the Associate Director for Fiscal Policy at the Center for American Progress.