When state governments suffered severe revenue losses as a result of the Great Recession, their balanced budget requirements forced difficult spending cuts in sectors such as health care and education. Cutting programs within these sectors when people needed them most only made a bad situation worse. Fortunately, the federal government does not have a balanced budget requirement, and the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 helped close 30 percent to 40 percent of state budget shortfalls. A rigorous study in the American Economic Review that controlled for state economic differences concluded that this federal aid had a significant positive impact on job creation at the state level.

Some states’ budget stabilization funds worked to further mitigate the impacts of the Great Recession. These funds are commonly known as rainy day funds. States use rainy day funds to save for unforeseen emergencies or economic hard times. They helped states avert more than $20 billion in spending cuts or tax increases in the aftermath of the Great Recession. While the size and scope of rainy day funds vary by state, one thing is clear: states with stronger rainy day funds fare better during turbulent economic times.

Rainy day funds are not just a stabilization tool, however; they go hand-in-hand with progressive policy. Rainy day funds can be used to harness progressive taxation for economic growth, to ensure a reliable safety net for struggling families, and to strengthen the public’s trust and confidence in state government. They can, and should, be used as a tool to grow the economy and protect middle and low income families during economic hard times.

Rainy day funds should respond to economic conditions

The core purpose of rainy day funds is to save money during good times in order to help make ends meet during bad times. The key questions for states managing a rainy day fund are when to put funds in and when to take them out. Some states use their own fiscal rules to govern rainy day fund deposits and withdrawals, while other states manage them on a more ad hoc basis.

Each state has unique factors to consider, but the most effective rainy day funds generally tie deposits and withdrawals to peaks and valleys in revenue collections and economic conditions. Making deposits when revenues are high minimizes the strain of rainy day fund savings on state budgets, and tying withdrawals to economic conditions such as the unemployment rate or revenue declines ensures that the funds are spent when they are needed most. Used in this way, rainy day funds help stabilize state economies during booms and busts.

State budget experts at the Pew Charitable Trusts and the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities recommend against placing arbitrary caps on the size of rainy day funds, which limit a state government’s ability to save appropriately for economic downturns. These experts recommend that states set savings targets and make deposits to reach those targets based on the volatility of their revenue collections, and Pew recommends that states conduct regular studies to identify major sources of volatility and present appropriate policy solutions.

While every state is different, the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities warns that a rainy day fund capped at 10 percent or less of a state’s annual budget will not be sufficient to cover revenue shortfalls in a medium sized recession, and suggests 15 percent as a more adequate target. As seen during the Great Recession, however, state rainy day funds do not eliminate the need for measures to be taken at the federal level, such as through federal stimulus funding. Federal support is especially important during particularly deep or prolonged economic slumps, which is why the federal government’s pivot to fiscal austerity that began in fiscal year 2011 was so disastrous for state budgets and the overall economy.

Rainy day funds harness the economic advantages of progressive taxes

State taxes tend to be regressive, meaning they burden low- and middle-income households more than those at the top. According to the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, the bottom one-fifth of households paid 10.9 percent of their income in state taxes in 2012, compared with 9.4 percent for the middle one-fifth, and just 5.4 percent for those in the top 1 percent. Rainy day funds can help states use progressive taxes—in which higher income taxpayers pay a larger percentage of their income than lower income taxpayers—to make their tax systems fairer and make their overall fiscal systems tools for economic stabilization.

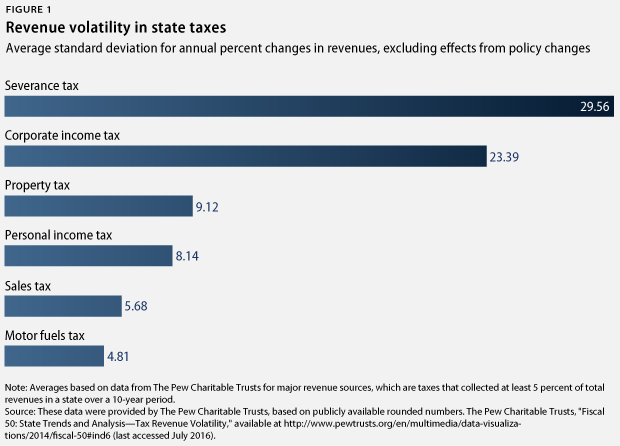

One reason that states utilize regressive taxes, such as sales taxes, is that they often generate a more stable stream of revenue than progressive taxes. Since state balanced-budget rules tightly link revenues to spending, legislatures may be choosing to avoid volatile revenue sources that could force disruptive spending cuts if their overall budget is not managed properly. But while stable revenues from regressive taxes may be easier to account for in the budgeting process, this choice comes at the expense of low- and middle-income taxpayers. And it should be noted that budget forecasts can also have significant errors for sales taxes, especially when a significant share of sales tax receipts comes from major purchases such as automobiles, for which total sales can vary greatly from year to year.

With a progressive income tax, households’ tax rates rise as their income rises and they move into a higher tax bracket; tax rates fall as income falls and households move into a lower tax bracket. Taxes on corporate profits and capital gains are also highly progressive, since these income sources are heavily concentrated among the wealthy.

Many of the most progressive tax sources are also highly volatile, often because fluctuations over the course of the business cycle cause changes in revenue collections. When wages decline during a recession, for example, households may fall into lower tax brackets under a progressive income tax. Likewise, unpredictable economic conditions make it difficult to accurately forecast annual revenues from taxes on capital gains and business income. The nature of this variation has historically made budgeting for these revenue sources difficult, but this is a missed opportunity to utilize fluctuations in tax collections to stabilize the overall economy.

Rainy day funds and progressive taxation are a perfect combination to promote stable, sustainable, and broadly shared economic growth. Progressive taxes are an automatic fiscal stabilizer for the overall economy. When the economy is struggling, a progressive tax system automatically reduces the tax burden on the private economy as business profits decline and individuals fall into lower tax brackets. This reduced tax burden helps struggling households make ends meet and enables them to patronize businesses. This promotes economic recovery.

The automatic tax reductions from progressive taxes during an economic slump could present a problem for state budgets if governments are left with inadequate revenues, but a rainy day fund uses volatile revenue as an asset by converting excess revenue during an economic boom into savings to be used during hard times. Thus, rainy day funds and progressive taxation work as a stabilization mechanism that increases savings during times of prosperity and promotes recovery during times of recession.

Case study: Massachusetts

Massachusetts uses its capital gains tax—12 percent for short term investments and 5.15 percent for long term investments—to sustain a sizable rainy day fund. The state allocates roughly $1 billion raised from the capital gains tax to its annual operating budget, which provides a reliable level of revenue for ongoing needs and saves the remaining funds to fill future budget gaps. Not only does Massachusetts link deposits into its rainy day fund to economic volatility, it does so by utilizing a progressive and volatile tax source.

In FY 2009, Massachusetts was able to avert approximately $1.4 billion in spending cuts or tax increases by using rainy day fund savings. These expenditures comprised 5 percent of the total Massachusetts FY 2009 budget of $27.9 billion. While the Massachusetts Legislature recently addressed a budget shortfall in part by increasing the amount of capital gains tax receipts supporting FY 2017 operating costs—and does not expect to contribute these revenues to its rainy day fund as a result—the design of the Massachusetts fund nonetheless serves as a model for effective rainy day fund policy.

Another application for rainy day funds is in resource-rich states, which apply severance taxes to the extraction of natural resources within a state. Severance taxes help ensure that a state’s natural resources benefit its citizens. Because of their dependence on the energy market, severance taxes are one of the most highly volatile sources of revenue a state can collect; therefore, they should not be used as the primary annual funding source for services such as education, health care, or public safety. Instead, severance taxes can be used effectively as a supplemental funding source for state services, for new investments such as the creation of parks and open space, or set aside in a rainy day fund. Resource rich and non-resource rich states alike benefit from using a variety of taxes to create a diverse revenue portfolio, in which different taxes respond differently to fluctuations in the economy.

Rainy day funds ensure a reliable safety net for struggling families

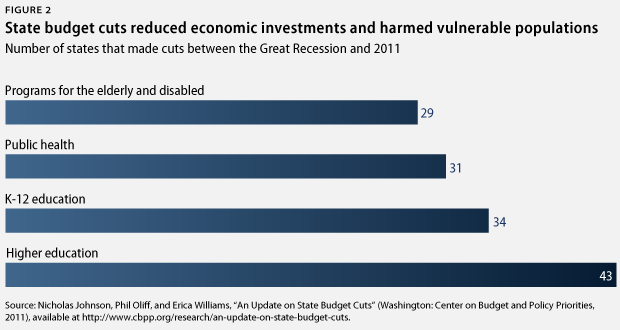

As a result of the Great Recession, states across the country suffered from a collective $110 billion budget gap during FY 2009. According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, in the aftermath of the Great Recession, 31 states cut public health, 29 states cut care for the elderly and disabled, 34 states cut K-12 education, and 43 states cut higher education. Many of these cuts disproportionately affected the nation’s most vulnerable populations and undermined key drivers of economic growth. Rainy day funds have the ability to support a variety of programs; in particular, they can serve as a safety net for social services programs, just as these programs serve as a safety net for struggling Americans.

Without the help of rainy day funds, total spending cuts could have been $20 billion larger after the recession. Strong rainy day funds fill in budgetary gaps and help states avoid making cuts that transfer the cost of the recession onto the most vulnerable. Oklahoma is tapping its rainy day fund this year as a result of falling oil revenues to prevent $51 million in cuts to its department of education, and $27.5 million to its department of corrections.

Politicians can be tempted to cut taxes during an economic boom when revenues are at unusually high levels. But when a subsequent recession causes a revenue shortfall, it leaves states with insufficient funds to sustain safety net programs that are facing increased demand. A rainy day fund can absorb a temporary increase in revenue collections and help state governments protect programs for vulnerable populations in times of hardship.

Rainy day funds strengthen public trust in government

Rainy day funds can build public trust in a state’s fiscal stewardship, which ultimately improves confidence in state government as a whole. A recent Gallup poll found that the public estimates that state governments waste 42 cents of every taxpayer dollar. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, or OECD, states that improving fiscal stewardship is a “key element” to rebuilding public trust.

Rainy day funds promote responsible and transparent budgeting to earn trust. Public finance researchers have found that rainy day funds help states save surplus revenues in a responsible and transparent manner. A well-managed rainy day fund helps mitigate political pressure from various interest groups to draw down surpluses for tax cuts or spending increases. This reduces the prevalence of less transparent ways to shield surplus revenues from political pressure, such as using biased budget forecasts to lower expectations for future revenue collections.

A rainy day fund signals to the public that a state government is capable of following through on its commitments and safeguarding its financial health. This communication of priorities has the potential to strengthen the public’s faith in a state’s ability to handle taxpayer dollars.

Conclusion

Rainy day funds utilize the volatility of progressive tax sources to help stabilize state economies through good and bad times. Instead of amplifying a recession by cutting programs that serve low- and middle-income families—such as support for people with disabilities, public health, and K-12 education—states can utilize rainy day funds to prevent cuts to programs that support vulnerable populations. Having a rainy day fund signals to the public that a state government is financially sound, which in turn has the potential to increase the public’s trust in the fiscal stewardship of elected officials. When the public trusts legislators to use their taxpayer dollars wisely, they are more supportive of proposed solutions to the challenges facing American families.

Harry Stein is the Director of Fiscal Policy at the Center for American Progress. Laura Pontari is an intern on the Economic Policy Team at the Center.

The authors would like to thank Elizabeth McNichol of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities and Brenna Erford of the Pew Charitable Trusts. Their insights and feedback on an earlier draft were extremely helpful. All opinions and any errors in this issue brief are the sole responsibility of the authors.