August marked the two-year anniversary of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, program. Apart from temporarily deferring their deportations from the United States, DACA also gives eligible undocumented youth and young adults access to renewable two-year work permits and Social Security numbers.

Two years out, we now have a clearer picture of the benefits DACA has provided many undocumented young people. It has allowed them to achieve better economic opportunity, attain higher education, enroll in health insurance, and participate more in their local communities.

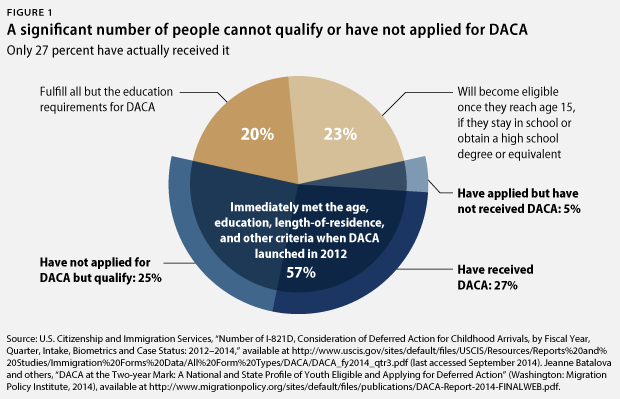

As of July, 587,366 undocumented young people had received both relief from deportation and a work permit, out of the more than 680,000 undocumented young people who have so far applied for DACA. However, many more can still qualify. Around 1.2 million undocumented young people were immediately eligible for the DACA program when it began, but an additional 426,000 could apply if they met further qualifications. Another 473,000 children, who are currently younger than 15 years old, will age into the program.

Additionally, in the coming months, hundreds of thousands of DACA beneficiaries will need to renew their DACA. Community organizations, families, and DACA beneficiaries themselves will need to make sure that they meet the renewal deadline and fees set by the U.S. Customs and Immigration Service. The stakes are high, as failure to renew properly could mean a loss of both work authorization and deferral from deportation.

Despite the challenges of renewing DACA and making sure more qualifying young people apply for it, DACA has significantly affected the lives of undocumented young people, as well as on the nation. It is also worth noting that DACA has laid the groundwork for future comprehensive immigration reform by starting the process of registering undocumented young people for potential legal status.

This issue brief discusses the top benefits that DACA provides immigrant youth and takes a look at how the program has helped our economy and society.

Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals

On June 15, 2012, President Barack Obama created a new policy that called for deferred action for eligible undocumented youth and young adults who came to the country as children. Under DACA, undocumented immigrants are granted deferral of deportation from the United States, as well as access to Social Security numbers and renewable two-year work permits.

To qualify for DACA, undocumented young people must meet the requirements listed below and pay $465 for filing fees and biometric services, such as fingerprints. So far, undocumented immigrants and their families have paid a total of more than $300 million in program fees.

To be eligible for DACA, unauthorized immigrants must meet the following official requirements from the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, or USCIS:

- Have passed a background check

- Have been born on or after June 16, 1981

- Have come to the United States before their 16th birthday

- Not have lawful immigration status and be at least 15 years old

- Have continuously lived in the country since June 15, 2007

- Have been present in the country on June 15, 2012, and on every day since August 15, 2012

- Have graduated high school, have obtained a GED certificate, be an honorably discharged veteran of the Coast Guard or armed forces, or currently attend school on the date that they submit their deferred action application

- Have not been convicted of a felony offense

- Have not been convicted of a significant misdemeanor offense or three or more misdemeanor offenses

- Not pose a threat to national security or public safety

In August 2014, renewals for DACA began. All 587,366 DACA beneficiaries must submit renewal request about 120 days before the expiration of their current period of deferred action. According to the official requirements from the USCIS, they must continue to meet the initial DACA guidelines, pay an additional $465 for filing fees and biometric services, and have fulfilled the following requirements:

- Did not depart the United States on or after Aug. 15, 2012, without advanced parole;

- Have continuously resided in the United States since the submission of the most recent DACA request that was approved; and

- Have not been convicted of a felony, a significant misdemeanor, or three or more misdemeanors, and not otherwise pose a threat to national security or public safety

DACA improves economic opportunities for undocumented young people

DACA has opened new doors for undocumented youth, leading to a stronger economy for everyone. Under DACA, undocumented youth are able to apply for and receive temporary work permits. For many, this means the ability to find a job for the first time. For others, it means being able to exit the informal economy and move on to better-paying jobs.

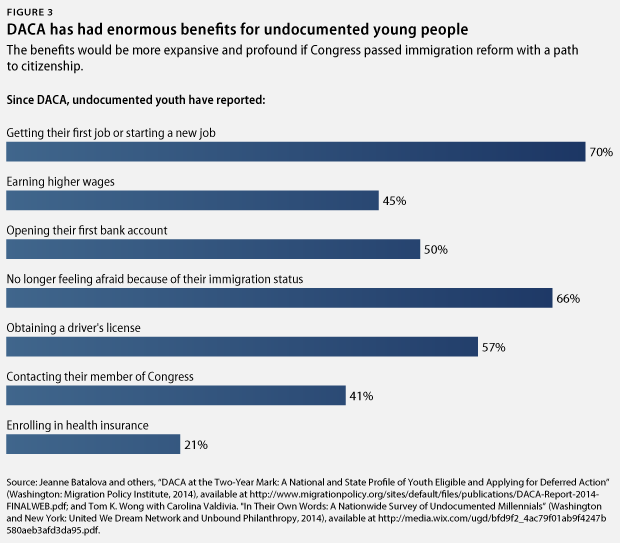

In fact, a recent survey of “DACAmented” young people—undocumented immigrants who have benefited from DACA—indicated that 70 percent of survey respondents reported getting their first job or starting a new job. Additionally, 45 percent reported an earnings increase.

It’s not just undocumented youth who have benefited from work permits, however; the United States as a whole has. Extending work permits to DACA recipients translates into higher tax revenues as these young people get on the books, earn more, and start paying more in payroll taxes. These revenues support vital programs such as Social Security and Medicare—even as undocumented immigrants are unable to access these and other social safety net programs.

Undocumented young people have also benefited in other ways. Almost 50 percent of DACA beneficiaries surveyed have opened their first bank account, and 33 percent have obtained their first credit card. These shifts allow young people to spend their new earnings on purchases throughout their communities and to generate new jobs as businesses strive to meet the higher demand for goods and services. These benefits are especially important because many undocumented young people live in economically vulnerable positions. According to The Migration Policy Institute, an estimated 34 percent of those immediately eligible for DACA lived in families with annual incomes below100 percent of the federal poverty line.

Undocumented young people can achieve higher educational attainment

While DACA has increased the ability of undocumented young people to achieve greater economic opportunity, some evidence shows that it is also increasing educational attainment. To qualify for DACA, a young person must have graduated from high school, passed the GED exam, or be currently enrolled in and attending school. An additional 426,000 undocumented young people could qualify for the program if they meet these educational requirements. This has encouraged more undocumented young people to return to school to complete their education and potentially transition to higher education.

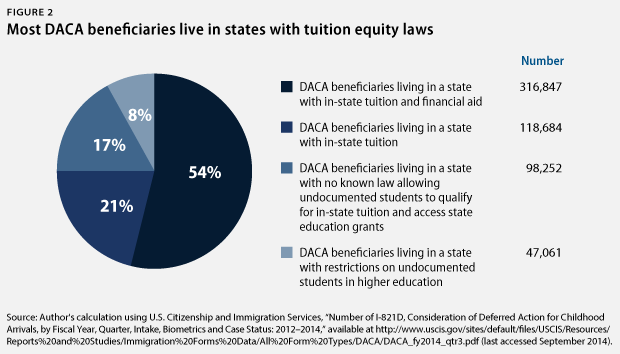

Additionally, DACA has helped some undocumented students complete higher education. In some states, such as Arizona, DACA recipients can enroll in some public community colleges at in-state tuition rates. Virginia recently changed its policy to allow DACA recipients to pay in-state tuition.

Over the past 14 years, states have taken action to allow undocumented young people to pay lower and more affordable tuition fees for their states’ public colleges and universities. In 2001, Texas was the first state to pass legislation that changed its residency requirements so undocumented young people could qualify for in-state tuition. Several states followed. California changed its requirements in 2001, while Utah and New York did so in 2002. Washington and Illinois changed theirs in 2003; Kansas changed its in 2004; New Mexico changed its in 2005; and Nebraska changed its in 2006. Maryland and Connecticut changed their requirements in 2011, and Colorado, Minnesota, New Jersey, and Oregon did so in 2013. Florida did so this year. Hawaii, Michigan, Oklahoma, Rhode Island, and Virginia also offer in-state tuition in many of their public colleges and universities; they do so through decisions of their state boards of higher education or advising from their state attorneys general.

DACA has also helped many undocumented students stay in school. The wider student population typically says that it leaves school due to a lack of academic preparation. Undocumented students, however, say that finances force them to leave. This phenomenon, known as “stopping out”—leaving higher education for a certain period of time but intending to come back—has been reduced by work authorization that allows undocumented students to hold higher-paying jobs in order to finance their education.

The Social Security numbers granted to DACA beneficiaries have also helped many undocumented students access financial help for higher education. Current federal law continues to prohibit all undocumented students from accessing federal financial aid, including Pell Grants and the Federal Work-Study Program. DACA beneficiaries, however, can still fill out the Free Application for Federal Student Aid, or FAFSA, with their Social Security numbers; this means they can receive their Estimated Family Contribution number, which allows them to petition their schools for institutional aid that is available to all students.

DACA reduces feelings of disconnect

Deferral-from-removal action and work authorization have given hundreds of thousands of undocumented young people increased peace of mind. DACA recipients can more comfortably move through their daily routines: Sixty-six percent of respondents to one survey agreed to the statement, “I am no longer afraid because of my immigration status.” Additionally, 64 percent agreed with the statement, “I feel more like I belong in the U.S.” Reduced feelings of disconnect can have enormous positive effects for individuals and their communities. It allows young people to have greater peace of mind, which translates to greater participation in the economy and in civic life.

Another survey showed that DACA has also enabled 57 percent of undocumented young people to obtain a driver’s license. Forty-eight states allow DACA recipients to obtain a driver’s license, with only two states—Arizona and Nebraska—prohibiting them from doing so. In these two states, DACA beneficiaries have access to in-state tuition at some public colleges and universities, but they cannot obtain a driver’s license to get around campus and the surrounding area.

Access to a driver’s license and identification cards means better safety for all drivers and has given undocumented young people greater job opportunities. Additionally, driver’s licenses and identification cards can have enormous effects on lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender, or LGBT, undocumented young people. About 10 percent of DACA recipients surveyed also identified as LGBT. This community—and, in particular, transgender individuals—often need proper identification in order to participate fully in society. Without this, undocumented LGBT immigrants can see heightened discrimination from law enforcement or other service providers.

Indeed, the National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs found that although undocumented immigrants account for less than 3 percent of the total adult LGBT population in the United States, they represent nearly 8 percent of LGBT hate violence survivors. However, LGBT and HIV-affected undocumented survivors of violence were 1.7 times more likely than the general LGBT community to report incidents to the police. This could be linked to mandatory first responder reports to the police or to greater education and outreach to LGBT undocumented survivors, who feel because of DACA that they can report violence.

Civic engagement and participation increases with DACA

While many undocumented young people were highly political prior to DACA, evidence shows that civic engagement has only continued to grow. More than 50 percent of respondents to a survey believed that their immigrant status empowered them to advocate for their community. This has led to civic participation rates that eclipse that of the general population. According to the 2012 American National Election Study, or ANES, only 6 percent of respondents participated in a political rally or demonstration, compared with 41 percent of DACA recipients. Additionally, 41 percent of DACA recipients had contacted members of Congress, compared with the 21 percent of ANES respondents.

DACA recipients also connect their families to civic life. More than 30 percent of DACA recipients reported getting most of their information regarding immigration, including immigration reform, from online sources. Another survey also indicated that 90 percent of DACA recipients have family that would benefit from immigration reform. Young people are a key source of information for their families on immigration policy issues, and they will be a cornerstone to advocate for the implementation of any future reforms for millions of other undocumented immigrants as well.

Undocumented youth have gained some access to health care

Although undocumented immigrants are not eligible for the Affordable Care Act, or ACA, DACA recipients have still gained more access to health care. Washington state, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New York, the District of Columbia, and California allow low-income DACA recipients to enroll in health insurance. By not using federal funds for the programs that help cover undocumented residents, these states were able to bypass restrictions around the ACA; the District of Columbia, for example, allows all immigrants regardless of status to enroll in health insurance. In California, as many as 127,000 DACA recipients qualify to enroll in exclusively state-funded Medi-Cal programs. The #Health4All campaign in California has engaged thousands of undocumented young people to learn if they qualify.

Additionally, many undocumented young people have enrolled in college or university health care plans or have received new employment-based plans. This has led to a 21 percent increase in the number of undocumented young people with DACA that have obtained health insurance. Greater enrollment in health insurance has enormous positive effects on public health.

However, these small fixes do not provide comprehensive care. DACA recipients are still barred from the ACA, and a recent report showed that, in California alone, 50 percent of undocumented young people delayed getting the medical care they needed. Of these people, 96 percent cited lack of insurance as the main reason.

DACA has benefited the families of undocumented young people

Undocumented young people are often not the only undocumented person in their family. More than 80 percent of DACA recipients reported having an undocumented parent, and more than half have undocumented siblings. In families where everyone is undocumented, DACA has allowed young people to provide more services to their families. Access to driver’s licenses, the ability to open bank accounts, and even things such as renting equipment from stores that they can use for employment, have allowed more undocumented families to participate in the economy.

More action is needed

DACA has provided enormous benefits to undocumented young people. However, 66 percent still report feeling anxious or angry because their families cannot qualify. About 2 million people have faced deportation during the past six years, the equivalent to wiping out the entire combined populations of Boston, Massachusetts; Miami, Florida; Seattle, Washington; and St. Louis, Missouri. These removals devastate communities and leave broken families behind in the United States. A recent Center for American Progress report outlines some of the executive actions President Obama should consider to repair our broken immigration system, including expanding deferred action to more undocumented immigrants.

Despite its successes, DACA has been only a partial fix, largely benefitting those with the most education. This is partly due to the ability of such young people to leverage their credentials in the job market. Additionally, more outreach is needed to make sure that all qualifying young people enroll or renew on time.

The benefits would also run much deeper and wider if Congress were to pass comprehensive immigration reform and create a pathway to citizenship for millions of undocumented immigrants. In the meantime, the president can expand the use of deferred action beyond DACA to other individuals who are not priorities for deportation given their length of U.S. residence, their stable employment, or the fact that they have children living with them. This expansion could help stabilize families, communities, and local economies across the country.

Zenen Jaimes Pérez is a Policy Advocate for Generation Progress, the youth division of the Center for American Progress.