This week, the U.S. House of Representatives will vote on H.R. 3, the Elijah E. Cummings Lower Drug Costs Now Act of 2019. H.R. 3 is a bold step toward reducing the high prices of prescription drugs through Medicare negotiation. The legislation gives the secretary of health and human services the authority to directly negotiate with drug companies for up to 250 of the highest-priced drugs—and all insulin—each year. The new, lower prices would be available to consumers with all sources of coverage, both public and private. Despite H.R. 3’s potential to dramatically lower prices for patients who rely on these drugs, President Donald Trump is opposing the bill, breaking his campaign promise to deliver lower drug prices.

New analysis by the Center for American Progress estimates that as a result of the H.R. 3 negotiation process, some diabetics could save more than $700 on an annual supply of certain types of insulin. Moreover, negotiation could bring down the net price for other types of drugs—including expensive treatments for cancer and multiple sclerosis—by thousands per month. Reform is desperately needed. Today, pharmaceutical companies set excessive prices that they increase over time in order to maximize profits. Prices for many drugs have skyrocketed, and nearly 1 in 4 Americans currently taking prescription drugs find them difficult to afford. Some people struggling to afford medication for chronic illnesses even turn to drug rationing in desperation, which can be lethal. In fact, a recent study found that 1 in 4 patients with diabetes ration their insulin in response to rising prices.

The American public overwhelmingly agrees that it is time to allow the government to negotiate with pharmaceutical companies: 85 percent of Americans support this tactic to reduce prices for Medicare and private insurance. Yet despite the policy’s popularity, and President Trump’s campaign promise to “negotiate like crazy” to reduce drug prices, the current administration opposes H.R. 3—the only bill that includes drug price negotiation. It should come as no surprise that the Trump administration is backpedaling on its claimed commitment to reduce drug company profits; some of the administration’s key players on health policy built their careers at pharmaceutical corporations.

How negotiation would achieve lower drug prices

At the heart of H.R. 3 are measures granting Medicare new powers to negotiate with drug companies, using international prices as a backstop. That reform alone would have a huge impact on drug costs for Americans. One study of 79 prescription drugs found that U.S. prices are nearly four times higher, on average, than those in comparable countries.

Under the process laid out in the bill, the secretary of health and human services would negotiate as many as 250 drugs each year. The negotiation process would prioritize drugs with the greatest savings potential—those that rank highest by spending, have no generic or biosimilar competitor, and have a large pricing gap between the United States and peer nations.

Manufacturers of drugs subject to negotiation would agree to a price no higher than 120 percent of the average price in other industrialized countries. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has estimated that H.R. 3 negotiations would result in an average discount of nearly 55 percent on current Medicare Part D net prices for the first group of drugs to undergo negotiations and a discount of 40 to 50 percent for drugs negotiated in subsequent years.

The bill would also bring down prices for new drugs, which could be among the most expensive in coming years. For example, Trikafta, a newly approved drug for cystic fibrosis, represents a big advance for treating the disease yet carries a list price of $311,503 per year. When international comparison data were unavailable, the H.R. 3 negotiation process would cap drug prices at 85 percent of the U.S. average manufacturer price.

Importantly, H.R. 3 would make these lower, negotiated prices available beyond Medicare to payers in the commercial market. Any drug manufacturers who refused to participate in negotiations or abide by the resulting maximum fair price would be subject to increasing financial penalties. The legislation also cracks down on companies that increase a drug’s Medicare price above the rate of inflation by subjecting those drugs to excise taxes. The CBO estimates that these changes together would save the federal government approximately $500 billion over the next 10 years, which the bill would reinvest to bolster Medicare benefits, increase funding for the National Institutes of Health and the Food and Drug Administration, and make other critical public health investments.

Estimated savings from negotiation

If the bill is enacted, Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in Part D plans would save on their prescription drugs in a number of ways. First, Part D beneficiaries who have yet to meet their plan’s annual deductible could save hundreds of dollars in out-of-pocket costs. Second, while beneficiaries who instead face a copayment or coinsurance at the pharmacy may not directly see the effects of drug price negotiations, the CBO projects that they would benefit from lower premiums and cost-sharing. Third, H.R. 3 uses federal savings from negotiations to pay for a new out-of-pocket maximum for drug spending for beneficiaries in Medicare Part D.

Consumers with private insurance would also save on their prescription drugs, as they would pay lower prices before meeting their plan’s deductible. Moreover, lower drug prices could in turn reduce premiums or cost-sharing depending on how consumers’ coverage is designed.

For CAP’s estimates of drug-specific savings, the authors created a list of drugs that are likely candidates for negotiations under the H.R. 3 criteria. These included drugs that were among the top drugs by aggregate spending in Medicare Part D in 2017 and are currently single-source drugs with no generic or biosimilar competitor. Insulin products would also be included in the first year’s negotiations.

Prescription drugs are transacted at various prices during their journey through the pharmaceutical supply chain, including the manufacturer’s sales price and the retail cost at the pharmacy. For this analysis, the authors started with each drug’s wholesale acquisition cost (WAC), also known as the list price, which is the only type of price defined in regulations. There is no single, publicly available catalog of WAC prices. Information on the WAC for a 30-day supply came from AnalySource. For insulin, the authors provided an illustrative example for a typical diabetic patient since insulin dosages vary among individuals.

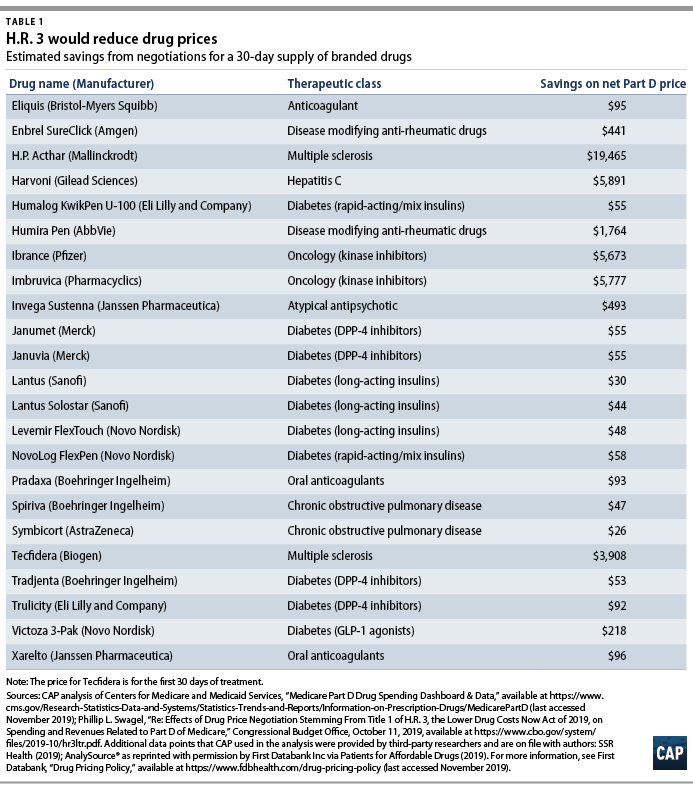

The authors’ approximated the current net Part D price by applying the average discount by therapeutic class as of the third quarter of 2019, according to an analysis of SSR Health data. The dollar savings, which are shown in Table 1, were calculated by applying the CBO’s estimated 55 percent discount to the estimated net Part D price. For patients who have not yet met their deductible, the savings represent a possible reduction in out-of-pocket costs; for others who might owe a smaller copayment or coinsurance, the savings would accrue to the payer and could be passed on to enrollees indirectly through lower premiums or cost-sharing.

CAP finds that negotiation would generate dramatic savings on many drugs. A 55 percent discount from first-round negotiations could lower the net Part D price for a 30-day supply of the cancer drug Ibrance by $5,673 and of the multiple sclerosis drug H.P. Acthar Gel by $19,465. In addition to negotiating down prices for drugs with the highest aggregate Part D spending, H.R. 3 would also lower the cost of insulin, a vital drug for management of diabetes. CAP estimates that the legislation would reduce the monthly net price for Lantus Solostar by $44, NovoLog FlexPen by $58, and Humalog KwikPen by $55.

Conclusion

By allowing Medicare to negotiate with drug companies and giving more consumers access to those negotiated prices, H.R. 3 has taken a strong first step toward lowering excessive drug prices. Without meaningful reforms including negotiation, the rising price of prescription drugs will continue to take a toll on families’ finances and, in the worst cases, cost lives. Three years ago, then-candidate Trump promised to support Medicare negotiations. His administration is breaking that promise by opposing H.R. 3.

Nicole Rapfogel is a special assistant for Health Policy at the Center for American Progress. Maura Calsyn is the managing director of Health Policy at the Center. Emily Gee is the health economist for Health Policy at the Center.