It has been a tough few months for accrediting agencies. These independent nonprofit organizations act as the gatekeepers to federal college aid: They must approve any institution that wishes to get access to student grants or loans from the federal government. A series of recent events—both from within and outside the federal government—have brought their ability to effectively perform this role into question.

In June, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) grilled the CEO of accreditation agency the Accrediting Council for Independent Colleges and Schools, or ACICS, in a congressional hearing for its ineffective investigations of for-profit colleges. ACICS accredited the now-defunct Corinthian Colleges, which is accused of faking job placement rates and defrauding millions of students. How, Sen. Warren inquired, could an accreditor ostensibly focused on quality assurance have allowed Corinthian to continue accessing federal financial aid dollars and enrolling students despite widespread evidence that it was committing fraud? Corinthian, after all, remained accredited until its demise.

Following the hearing, authors Andrea Fuller and Douglas Belkin called accreditors the “watchdogs that rarely bite,” in a high-profile Wall Street Journal article. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau issued an investigative demand to ACICS seeking information about the for-profit schools it oversees. Later, a Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations opened an investigation on the role of accreditors in assessing the quality and financial stability of institutions, and it is requesting the records of numerous agencies, with an enhanced focus on ACICS. To top it all off, in November, the Department of Education released new data about student outcomes—including graduation rates, loan repayment, and job earnings—by accreditation agency and called upon Congress to repeal legislation that currently bans the department from defining or setting standards of student achievement that accreditors must address when reviewing colleges.

Confronted with claims that the accreditation process is ineffective, accreditors consistently claim that their historic role has been about quality improvement, not accountability. After meeting with The Wall Street Journal’s editorial board, Judith Eaton, president of the Council for Higher Education Accreditation, or CHEA—an umbrella organization for accrediting agencies—made the case that accreditation agencies are under increasing pressure to do more to protect students. Her argument concludes that the largest game changer for accreditation is an increased urgency to protect students against institutions with poor student outcomes such as high debt, student loan defaults, and low graduation rates.

CHEA and the rest of the accreditation establishment, however, are missing a crucial point: The expectation that accreditors protect students and taxpayer funds is nothing new. In fact, a review of major higher education legislation from World War II through the last reauthorization of the Higher Education Act in 2008 shows that consumer protection has always been the main purpose of federal legislation regarding accreditation. That was the case in 1952, when Congress first leveraged the independent accreditation system as a way to prevent bad actors from receiving federal funds. It still was the goal in 1992, when Congress rewrote many of the rules around accreditation. And it remains true today. If accreditors are still incapable of performing this role, policymakers should explore alternative ways of determining which institutions can and cannot access federal aid.

The origins of accreditation

From the very beginning of the federal reliance on accreditors, the role of accreditation agencies with respect to federal financial aid has been about protecting consumers and preventing fraudulent actors from receiving taxpayer dollars.

The college accreditation process, however, long predates the advent of federal student aid programs; the first accreditation agencies appeared in the late 1800s. At that time, there were a wide range of colleges and universities with differing admissions requirements, curricula, and required lengths of study to earn a degree. A lack of universal standards made it difficult for institutional administrators to determine the differences between programs at secondary schools, colleges, and graduate schools. For institutions, the variation in curricula and degrees complicated the transfer of credits when students transferred. Similarly, institutions had difficulty assessing whether students from other countries were qualified for college or graduate school.

Colleges and universities created accreditors as voluntary membership associations designed to provide clarity and establish curriculum, degree, and transfer of credit standards through a peer-review process. As voluntary associations, representatives from the member colleges were responsible for establishing standards and ensuring that schools met those standards. If a school was accredited, it sent a signal to other institutions that the education it provided was in line with its own quality standards. And for decades, accreditation stayed that way—a separate and voluntary process that had no interaction with the federal government.

Today’s accreditors

In order for an institution’s students to access federal grants and loans for college, it must first be accredited. Today, there are 37 accrediting agencies of varying types. Seven regional accreditors are the largest agencies and oversee a majority of public and private nonprofit schools in addition to some for-profit colleges. Each of these accreditors is responsible for schools in a different geographic area. The second-largest category of accreditors is national accreditation agencies, which tend to focus on a specific type of school. For example, national accreditors might focus on overseeing career schools, art schools, or bible colleges. Most schools that are nationally accredited are for-profit colleges and tend to offer career-specific programs.

Beginning of federal education dollars and fraud

In the 1940s, however, the federal government’s role in higher education began to change. Increased federal involvement and spending created a new set of problems that, eventually, accreditors were relied upon to address.

The 1944 GI Bill

Starting with the 1944 Servicemen’s Readjustment Act—more commonly known as the GI Bill—the federal government began to provide financial aid directly to returning veterans so that they could attend college. From 1944 to 1951, the government spent $14.5 billion on the education and training of 8 million GIs returning from World War II. At first, these dollars were largely unrestricted; veterans could use the money at traditional colleges and universities, vocational training programs, and on-the-job and on-farm training programs. The Veterans Administration administered the federal funds; all it took for educational providers to qualify for federal dollars was approval from a state agency. The GI Bill required that state agencies furnish a list of educational and training institutions qualified to provide training, leaving the task of determining which institutions were worthy of receiving funds to the states.

While the GI Bill was groundbreaking legislation that provided educational opportunity for millions of veterans, it also gave rise to a seedy subindustry of fly-by-night operations. Over the five years following the passage of the GI Bill, almost 6,000 for-profit schools sprung up and took advantage of the new federal education funds. In response, several government entities launched investigations into potential fraud and abuse, including action by the Veterans Administration; the Bureau of the Budget, the predecessor to the Office of Management and Budget; and additional committees formed by the U.S. House of Representatives and the General Accounting Office.

These studies concluded that many of the programs and schools created had no educational background and experience, charged unreasonable and excessive fees, faked attendance records, manipulated state authorities, and offered training in fields with little to no potential for jobs.

An investigation by the House Select Committee to Investigate the Educational, Training and Loan Guaranty Programs Under the GI Bill—known as the Teague Committee for its chairman, Rep. Olin Teague (D-TX)—found that in the state of Pennsylvania, “it was common knowledge among school operators that it was customary to pay inspectors and give them gifts.” In one instance, a school operator who also owned an automobile agency sold a state official two cars at an unreasonably low price and installed accessories for which the state official was never charged. A second Teague Committee report found that there was inadequate reporting and student tracking that resulted in more than $200 million in overpayments to veterans. Because veterans and institutions failed to notify the Veterans Administration when a student dropped out of training, the administration continued payments to students who were no longer enrolled. These investigations demonstrated that the system of state approval, broadly defined, was an insufficient check on keeping out bad actors.

The 1952 GI Bill

Faced with the need to weed out bad college actors and protect students, Congress turned to the accreditation system. In the next authorization of higher education benefits for veterans—the Veterans’ Readjustment Assistance Act of 1952—Congress required that institutions receiving GI Bill funds must be accredited. To assist with this task, Congress required the Office of Education—located in the Federal Security Agency, the precursor to the U.S. Department of Education—to publish a list of recognized accrediting and state agencies.

Obtaining accreditation was not, however, the only way a college could still receive federal assistance. Unaccredited nonprofit and public institutions could still access federal aid if they showed that three accredited schools would accept their credits. Alternatively, unaccredited institutions—including for-profit institutions—could seek approval from state agencies to access federal funds if they completed an application process and underwent an investigation to prove that they were a legitimate operation. State agencies were required to determine that an institution was in line with the standards of other accredited institutions in the state, in which case they also would become eligible for federal money.

Since the passage of the second GI Bill, the federal government’s relationship with accreditors has been intended to protect students and taxpayers’ investments by keeping out fraudulent actors. There was no discussion in these early pieces of legislation about having accreditation agencies work with colleges to improve quality. Relying on accreditors was in some ways an intentional abdication of federal power: The government did not try to create its own oversight system. Rather, it relied on a system that was already in place. But by authorizing a system originally created for quality standards at nonprofit, traditional four-year universities to control the flow of federal funds to a much wider array of institutions, Congress also set the grounds for the quality improvement vs. consumer and taxpayer safeguarding fight that continues today.

Expansion of federal aid grants and loans broadened reliance on accreditors

Buoyed by the success of the GI Bill, the federal government expanded its federal assistance for college in the 1960s and 1970s to cover students beyond those who had served in the armed forces. Throughout this time, the federal government continued the precedent it set in 1952 by relying on accreditation as the gatekeeper for deciding who could access government dollars.

The two biggest expansions in federal aid for college over this period took place in 1965 and 1972. In 1965, Congress passed the Higher Education Act, or HEA, which opened federal grants and loans to all students who wanted to pursue postsecondary education. The bill limited access to federal grants and loans to accredited public and nonprofit institutions. Similarly, the 1965 National Vocational Student Loan Insurance Act allowed for-profit business and trade schools to access federally insured loans—but not grants—if they had accreditation.

The 1972 HEA reauthorization further broadened the type of education providers eligible to receive federal financial aid by allowing grants, in addition to previously authorized loans, to be used at accredited business and trade schools. At the same time, the amendments expanded the volume of federal aid available to students by creating the Basic Educational Opportunity Grant for low-income students, now known as the Pell Grant.

In the 1965 and 1972 amendments, which made expansions to student aid, the federal government continued to rely on accreditation as the process for determining which institutions could receive support. While both acts made it clear that accreditation was the preferred standard for accessing federal aid, they included exceptions to this rule. Under the HEA, unaccredited nonprofit and public schools had to be making reasonable progress toward accreditation, as determined by the commissioner of education, or have three accredited schools accept their credits. The National Vocational Student Loan Insurance Act of 1965, meanwhile, required that unaccredited schools be certified by a state agency or a committee established by the federal commissioner of education if no agency existed.

Even though the HEA expanded aid eligibility to a variety of very different institutions with different missions and approaches to education, it did not contemplate any sort of change to the role that accreditation should play in determining which institutions could receive federal funds. None of the legislative changes addressed how accreditors should carry out assessments despite the rapidly expanding range of institutions they were required to review.

The cumulative result was that by 1972, Congress brought the role of accreditation to sectors of higher education it was not created to serve, leading to the creation of many new accrediting agencies focused only on approving for-profit schools. Before Congress made accreditation a prerequisite for government support, it had, for the most part, existed for quality assessment at traditional public and private nonprofit schools. Although some accreditors focused on career education prior to the federal government’s accreditation requirements, a majority of the accreditors that oversaw for-profit institutions were created after changes in the law. As a result, new entities emerged in the accreditation space having no history of serving a quality improvement function and no road map for how they should think about quality differently.

An attempted crackdown on widespread waste, fraud, and abuse

By the end of the 1980s, it had become increasingly clear that accreditation alone was an insufficient check on determining which colleges could receive federal student aid. Beset by concerns about rampant waste, fraud, and abuse, Congress created more formal roles for states and the federal government to act as gatekeepers as well. As with prior federal efforts, the emphasis was on ensuring that bad actors could not gain access to federal funds.

Student debt at for-profit trade schools was a significant problem in the 1980s. These institutions had almost four times the default rate as traditional schools. Over a period of six years, loan defaults at these institutions increased 338 percent, to 39 percent. For-profit schools were leaving too many with high debt, no degree, and an inability to pay back their loans. These results prompted numerous federal investigations, including a highly publicized one led by Sen. Sam Nunn (D-GA).

The Nunn investigation, which included numerous hearings, found that accreditation failed to protect against fraud at for-profit institutions. Many of the witnesses in the hearings testified that accreditation was not well-suited to provide oversight of for-profit schools because the concept was based on traditional two-year and four-year schools, not for-profit businesses. These investigations turned up troubling findings such as for-profit schools securing accreditation by purchasing accredited nonprofit schools, creating new branch campuses without checks on quality, and bribing and manipulating accreditors. To fix the problem, the Nunn committee’s final report recommended that Congress create minimum quality standards for all accrediting agencies, as well as uniform consumer protection standards.

Shortly after the Nunn committee wrapped up its work, the 1992 HEA reauthorization laid out a vision that clearly defined what Congress expected of a gatekeeper. The law tried to make up for the failings of accreditors by being more explicit about what accreditors had to assess when they gave schools access to financial aid. Adding states as a primary oversight authority acknowledged that accreditation alone was not sufficient and that there needed to be someone checking the gatekeeper.

Acting on the Nunn committee’s recommendations, the 1992 HEA amendments focused on improving gatekeeping for federal aid by strengthening the role of state oversight. The act created new State Postsecondary Review Entities, or SPREs, to work with the Department of Education and identify problematic institutions. Under the law, each state would establish an authority to conduct oversight and define acceptable standards for its institutions. Standards had to include potential indicators of abuse, including high default rates, a majority of institutional funding derived from federal financial aid, and high year-to-year fluctuation of amounts received through financial aid.

States had the freedom to determine how high or low to set the bar of what was deemed acceptable performance, but the secretary of education had final authority over approving the standards in each state. Once states established a reliable authority, defined minimum standards, and received approval from the secretary, they would then review all of the institutions in their state. Any institution that did not meet the standards would be subject to a second, more thorough investigation by the SPREs. If the institution was not in compliance, the Department of Education could then use negative reviews from SPREs to bar access to federal financial aid.

The 1992 amendments not only created the first set of federal standards for how accreditors should do their job but also strengthened oversight through other means. First, the secretary of education received new authority to establish standards for approving accrediting agencies that they would have to meet before serving as gatekeepers to federal aid. Second, the 1992 HEA bill also defined specific indicators that accreditors had to create standards around when approving schools for accreditation. The list of requirements included the same indicators that would be measured by state review agencies.

Accreditor assessment standards

The Higher Education Amendments of 1992 required accreditors to assess a list of quality indicators:

- Curricula

- Faculty

- Facilities, equipment, and supplies

- Fiscal and administrative capacity as appropriate to the specified scale of operations

- Student support services

- Recruiting and admissions practices, academic calendars, catalogs, publications, grading, and advertising

- Program length and tuition and fees in relation to the subject matter taught and the objectives of the degrees or credentials offered

- Measures of program length in clock hours or credit hours

- Success with respect to student achievement in relation to its mission, including, as appropriate, consideration of course completion, state licensing examination, and job placement rates

- Default rates in the student loan programs under Title IV of this act, based on the most recent data provided by the secretary of education

- Record of student complaints received by, or available to, the agency or association

Finally, the 1992 amendments eliminated the provision permitting institutions that got three other institutions to accept their transfer credits to access federal student aid, requiring instead that all institutions receiving funds be accredited without exception. The 1992 reauthorization established accreditation as the only available route to participating in the federal aid programs, while providing additional state and federal oversight in a gatekeeping role.

What was supposed to be a shared gatekeeping role ended up losing state support soon after the passage of the 1992 amendments. State support for SPREs was lukewarm to begin with: States that were already strong on oversight supported SPREs, while those that did not have strong oversight or had a small number of institutions opposed them. Some states were already involved with accountability and actively pursuing oversight within their states and objected to the dominance of the Department of Education. Other states did not have the same high default rates as other states and found the requirements unnecessary.

The higher education community also objected. Individual institutions were caught by surprise when the Department of Education began to notify approximately 2,000 institutions that they had failed to meet at least one of the requirements laid out in the law and would be subject to a more thorough investigation. Private colleges were particularly outspoken against SPREs because they wanted to maintain independence and viewed the standards outlined in the law as a threat to institutional autonomy and freedom.

In November 1994, the newly elected House majority—led by Speaker Newt Gingrich (R-GA)—promised to reduce government regulation under its Contract with America. Already unpopular, SPREs were a prime target for elimination. Eventually, Congress withdrew funding and eliminated the legal requirement of state review agencies. States no longer had spelled-out expectations for reviewing institutions and serving as gatekeepers.

The plight of SPREs was a harbinger of what was to come for the role of the federal government’s oversight of higher education funding. Following the original passage of the 1992 amendments, the pendulum swung quickly back in the direction of deregulation: New accountability measures lasted just less than two years. The changes were discarded before state review agencies and accreditors could ever implement stronger oversight.

The federal government backtracks its reliance on states and accreditors for oversight

Following the backlash against the 1992 HEA reauthorization, legislative changes continued to claw back at the strict federal standards imposed on accreditors and institutions under the law. Future reauthorizations of the HEA reflected a reduction in what was required of both states and accreditors.

After walking back state accountability following the 1992 amendments, the 1998 amendments to the HEA reversed many of the new requirements aimed at accreditors. For instance, Congress eliminated the requirement that accreditors check tuition and fees in relation to subject matter and program length. The 1998 bill also eliminated a requirement that accreditors review default rates and conduct their own investigations, with one saying they had to review a record of compliance with default rates provided by the secretary. It also eliminated mandatory unannounced site visits for vocational programs, making them optional. Together, the dialed-down language and requirements reflected the view of the new House majority that the federal government should stay out of the business of enforcing standards altogether.

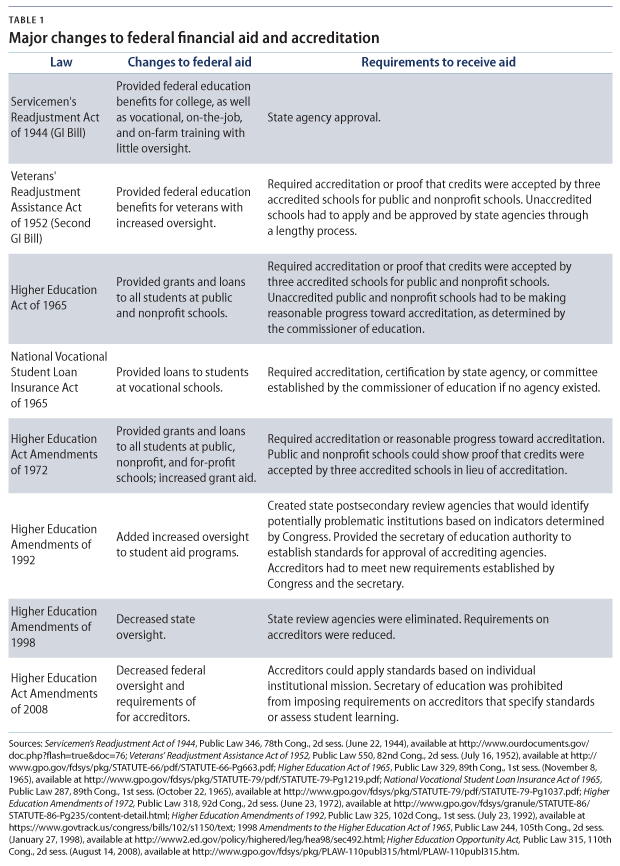

The 2008 HEA amendments continued the trend—started in 1998—of reducing the role of the federal government, giving accreditors greater freedom to act without strong oversight and affording institutions more leeway. First, the amendments required that accreditors apply quality standards with respect to the individual institution mission. In effect, this made accreditors serve the role of gatekeeper while letting schools define what it takes to unlock the door. Second, the act prohibited the secretary of education from establishing standards that accreditors have to abide by in assessing student achievement. All of the changes combined made accountability increasingly difficult to demand and even harder to define. For a table describing major changes to the HEA after 1992, see the PDF.

Conclusion: Looking forward

In the years following 2008, there has been a growth of the same problems that were seen in the 1950s and 1980s and 1990s in terms of concern about for-profit fraud. A 2012 Senate committee investigation led by Sen. Tom Harkin (D-IA), for example, found significantly lower completion rates, higher student loan debt, and higher loan default rates in the for-profit sector when compared with public and nonprofit institutions. Instead of refocusing on accreditation, as the 1992 amendments sought to do, the federal government has increasingly sought alternatives to accreditors for the purpose of protecting access to federal student aid.

Some of this has been accomplished through federal regulations administered by the Department of Education through negotiated rulemaking. The Obama administration has enacted two major regulations aimed at rooting out fraud. One, known as gainful employment, judges career training programs based on how much their graduates earn upon graduation vs. the debt borrowed. If a program is in violation, it loses access to federal funds. A second attempt—the state authorization standards, which has been challenged in court and has yet to go into effect—includes state authorization regulations. The rule requires institutions offering distance education to students in a state where they are not physically located to meet requirements in each state where they have students. The goal is to create a more formal role for states in approving schools.

Gainful employment, state authorization, and the executive actions announced earlier this month are all important efforts to create greater accountability among institutions that receive taxpayer funds. Accreditors, however, remain the primary gatekeepers. The legislative history of accreditation shows that fraud and abuse of the federal aid system have persisted despite repeated attempts to enact oversight and steer accreditors toward consumer and taxpayer protection. If accreditors are incapable of performing this function, then maybe it is time for an entirely new gatekeeper.

Antoinette Flores is a Policy Analyst on the Postsecondary Education team at the Center for American Progress.