The United States tax code is full of provisions designed to encourage or reward specific behaviors, such as owning a home or saving for retirement. Tax benefits for higher education are no exception: Contributions to some college savings accounts grow tax-free, college tuition is often tax deductible, and some student-loan borrowers are able to deduct the interest paid on their student loans just as they would the interest paid on their mortgage.

These higher education tax provisions have implications for access, affordability, and equity. Higher-income families benefit from tax-free savings toward future college costs through Section 529 college savings plans. The tax code, however, rewards middle-class families for savings less, because tax benefits are much smaller for those in lower tax brackets, and these families largely do not participate. While in school, parents and students face several competing tax incentives—such as the American Opportunity Tax Credit, Lifetime Learning Credit, and tuition and fees deduction—and an estimated 1.7 million tax filers each year do not make the optimal choices. In addition, the tax benefits available on student-loan interest help some struggling borrowers, but not others, because some earn too little to truly benefit.

Given that the federal budget contains more than $1 trillion in annual tax expenditures—government spending delivered through tax breaks or exceptions—it is no surprise that these expenditures face increased scrutiny. As tuition costs and student-loan debt have both increased dramatically, tax provisions should change to ensure the best possible outcomes for parents, students, and graduates.

Several recent proposals have argued for major changes to the tax code for higher education, including House Ways and Means Committee Chairman Dave Camp (R-MI)’s vision of tax reform released in February. Rep. Camp’s proposal would preserve and slightly expand the American Opportunity Tax Credit, which provides a refundable credit to low-income college students. It would also limit the use of retirement funds to pay for higher education, and tax the growth of large university endowments, among other provisions.

Unlike these broad proposals, this brief does not propose a comprehensive reform of the higher education tax system. Such an effort would overlap with many provisions and principles that exist throughout the tax code, such as retirement savings that can also be used for education, the tax advantages of charitable contributions, and the deduction of interest. Instead, this brief presents a menu of potential ideas for making each stage—before enrollment, during enrollment, and post-enrollment—more effective and equitable in terms of directing tax incentives to those who would benefit most from them.

Background

Overall, higher education tax benefits are a small piece of the tax pie; of the more than $1 trillion in tax expenditures, only about $40 billion in tax breaks flow to higher education. Excluding the deductibility of donations to colleges and universities as well as some benefits that go directly to institutions, individual tax expenditures for higher education are only about $30 billion, or less than 3 percent of the overall tax expenditure budget. In addition, this estimate is somewhat fuzzy considering that these provisions are tied to other aspects of the tax code, such as whether college students can be counted as dependents for tax purposes—a provision worth more than $5 billion in itself—and whether tuition payments are made through withdrawals from non-education savings vehicles such as retirement accounts.

Table 1 (available in PDF) details the current higher education tax expenditure provisions. Notably, tax expenditure estimates are unable to fully account for substitutions. In other words, eliminating one of the tax provisions would not automatically add back the full amount of revenue because individuals might take advantage of other tax benefits or change their financial habits in other ways.

While these expenditures of approximately $30 billion are small in light of the overall tax code, they are highly relevant in terms of the Department of Education’s overall spending, effectively doubling government funding for higher education affordability. In fiscal year 2013, approximately $33 billion was spent on Pell Grants and programs such as work-study to help low-income students attend college, with another $2 billion going to higher education programs for students and schools. And 18 million tax filers—about 13 percent of all Americans who file taxes—claimed at least one higher education-related tax benefit in 2009, according to the Government Accountability Office, or GAO. In effect, the tax code greatly magnifies the federal government’s support for higher education.

Despite its small size overall, the higher education component of the tax expenditure budget has the power to directly affect millions of students if implemented properly. And if not, it represents another form of government spending that does not improve financial outcomes. For example, tax-advantaged college savings plans known as Section 529 plans—named after the section of the tax code that created them—have grown dramatically since the 1990s to encourage families to plan ahead for college. Yet only 3 percent of households participate in these plans—and 70 percent of these participants earn over $100,000, making them likely to save for college anyway. And the deductibility of college tuition and fees—in which 45 percent of the tax benefits go to tax filers earning over $100,000—is a financial reward, but may not be an incentive for parents to make specific college spending choices. Furthermore, students’ and parents’ current tax choices—such as the availability of two different tax credits and a deduction for expenses while in school, each with their own eligibility criteria—needlessly confuse families and complicate the tax system. The GAO has noted that nearly $800 million in tax benefits to families are lost due to approximately 237,000 parents and students taking a financially disadvantageous deduction or credit rather than the tax provision that would save them the most money—and 1.5 million tax filers miss these deductions and credits entirely.

There are components of the current tax code, however, that do work. The American Opportunity Tax Credit provides a refundable credit to low-income students—effectively giving them money back for their tuition even if they do not owe federal income taxes. And in evaluating the overall tax system, there are principles to improve fairness for taxpayers—such as converting deductions to credits—as the Center for American Progress discussed in its comprehensive tax plan released in December 2012.

Credits directly reduce the amount of tax that is owed to the government, while deductions reduce the overall income that can be taxed. While deductions benefit higher-income earners more because they would owe more in taxes for every dollar earned, credits benefit all eligible tax filers equally. A $1 deduction results in an upper-income taxpayer saving nearly 40 cents in federal taxes, while a middle-class taxpayer may only save 15 or 25 cents on his or her taxes, if at all.

Another guiding principle is simplicity. There are currently multiple ways to save for college through the tax code—including through college savings plans as well as retirement accounts and savings bonds—each with their own rules. In July 2013, the Center for American Progress released a proposal for a Universal Savings Credit, which would streamline savings incentives and convert all savings-related deductions into a single credit. These steps are applicable to higher education as well.

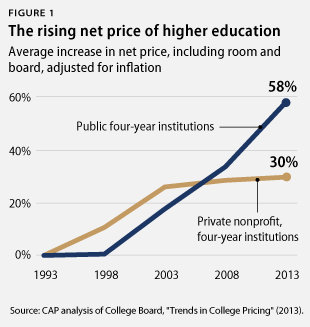

These changes are particularly important given rapid tuition increases and affordability constraints, as shown in Figure 1. Over the past two decades, even after adjusting for inflation, the average amount that families pay for tuition, fees, and room and board at four-year private colleges and universities increased by 30 percent. Meanwhile, at four-year public colleges and universities, average total costs increased by 58 percent after adjusting for inflation.

State funding cuts have also contributed to decreasing affordability. State funding is a far smaller share of public institutions’ overall revenue than a decade ago, declining from 31 percent of revenue to 22.3 percent between FY 2003 and FY 2012. Public colleges and universities have made up the difference through tuition and fees, which were 20.3 percent of total revenue in FY 2012, compared to 14.9 percent in FY 2003. And an increasing share of tuition revenue at public colleges comes from federal student-loan borrowing, which increased from 68.1 percent of tuition revenue in FY 2003 to 77.4 percent in FY 2012.

Changes to the tax code should also include the potential to raise additional revenue. Rep. Camp’s tax plan suggests taxing 1 percent of earnings on colleges’ endowments if they exceed $100,000 per student. Endowments are intended to enable colleges and universities to continually thrive over time through stable funding and savings in case of an economic downturn. But in recent years, endowments at private institutions have recovered from the financial crisis, and have grown dramatically on average: nearly 10 percent between 2008-09 and 2009-10, and nearly 17 percent between 2009-10 and 2010-11. As these endowments grow, limiting their tax-free buildup would incentivize schools to pass on these gains to middle-class students by making tuition more affordable and enrolling more students with financial need.

Before college: Making college savings more progressive

College savings accounts in Section 529 plans have grown over the past two decades as a way to save for college tax-free. These plans are created and administered by individual states who contract with investment firms to run their college savings programs. While contributions to these accounts do not have an immediate federal tax benefit, earnings in these accounts are never taxed as long as contributions are used to pay for higher education expenses. Otherwise, the earnings—but not the contributions—are taxable, plus a 10 percent penalty. And in the majority of states, contributions are tax deductible for state income tax purposes. This double benefit is an unusually generous combination for savers, since savings provisions in the tax code are generally designed to provide either an upfront tax benefit or a tax-free withdrawal, but not both.

While 529 plans are the main form of tax-advantaged college savings, they are not the only form. Coverdell Education Savings Accounts are another savings mechanism that can be used for school expenses at the elementary or secondary level as well as for college. And U.S. savings bonds are another form of tax-advantaged savings that have existed for decades, but are barely a blip on the budgetary radar, adding up to about $10 million a year in tax savings. While paper bonds are no longer sold at financial institutions, electronic savings bonds are available online, and a portion of one’s tax refund can also be placed in a paper savings bond.

In principle, college savings accounts are a good idea, and are certainly a valuable planning tool. At the same time, decades of experience with tax-advantaged savings vehicles such as retirement accounts have demonstrated that among higher-income families—who gain the most financially from these incentives—many would have saved anyway.Instead, savings incentives in the tax code should be simplified and made more flexible, as the Center for American Progress proposed last year through a Universal Savings Credit: a single tax incentive for a variety of savings goals that affects all tax filers equally, instead of deductions that overwhelmingly benefit the top. Matching contributions for low- and moderate-income savers would also be a stronger incentive than tax deductions.

As a result of the way savings incentives are currently structured, it is not surprising that while the concept is attractive, college savings plans such as 529s and Coverdells are overwhelmingly used by a small number of well-off Americans. While $167 billion was invested in 529 plans in 2011, 529s and Coverdell accounts combined are held by less than 3 percent of households, with the benefits overwhelmingly flowing to the highest-income earners. The median income of 529 and Coverdell account holders is $142,000—three times the national median. And the median wealth of families with these accounts is 25 times that of families without accounts, suggesting that many 529 plan participants already have significant financial resources. While Coverdells have an income limit, 529s do not, unlike many other savings provisions in the tax code. 529s also have virtually no limit on overall contributions, though gift tax provisions may apply and technically new contributions are prohibited once the account balance exceeds potential higher education costs. As a result, 529s in particular are a major mechanism to transfer wealth, but also perpetuate inequality, with tax benefits often flowing to those who need them the least. Indeed, some recent media accounts tout the use of education savings accounts for computers and iPads—certainly valuable tools for college students, but perhaps not ones that require the benefits of tax-free compounding.

Recognizing these limitations, states, counties, and cities have recently strived to make college savings programs more progressive both by offering matching funds to families who save for their children’s futures and by automatically opening accounts for children with an initial contribution. Eleven states currently match families’ contributions to 529 plans in some form. Maine now opens college savings accounts for newborns with a $500 deposit, funded by philanthropic contributions. San Francisco and other cities have established accounts for entering kindergarteners, and in some cases, match families’ contributions as well. These are promising first steps, but further action is needed to truly make these plans progressive.

- The Treasury Department should establish a national standard for gift contributions to 529s. Family members, friends, and community organizations may wish to make contributions for the future benefit of a child rather than directly to his or her parents or guardians. Yet there is currently no way to do this easily and consistently. In some cases, the contributor would need to know the child’s Social Security number as well as the plan in which the child is enrolled—since most states have at least one plan and some even offer multiple plans—yet few families have plans at all. Some states facilitate gift contributions by requiring only an account number, and some private firms currently will process gift contributions for a fee. Yet for decades, savings bonds were available as gifts to children without requiring this level of detailed information. A technological solution could make the same possible for 529s, potentially without requiring an act of Congress, and would facilitate savings contributions from multiple sources, including nonprofits that could provide families with financial support for future college costs.

- Congress should establish an annual contribution limit to 529s and cap tax-free buildup within them. Virtually no other tax benefit for individuals’ savings is currently limitless. Retirement accounts, whether pre-tax or after-tax, have contribution limits, and college savings plans should as well. This ensures that these plans actually encourage new savings rather than merely a shifting of assets by higher-income earners to more tax-friendly options. Gift tax provisions currently become effective for some contributors at $14,000 per year, after which contributions must be reported to the Internal Revenue Service, or IRS, though they may not be taxable. If this limit were applied to all contributions per child each year, accounts could still largely or entirely fund higher education without providing an excessive tax break. And capping the account balance that can grow tax-free at $200,000 would ensure that families are encouraged to save, but that tax benefits do not continue to accrue at the highest income and contribution levels.

- Congress should simplify higher education savings provisions and add a matching component. The savings system is already too complex. Coverdell accounts are used infrequently, and a number of proposals, including Rep. Camp’s tax plan, call for their elimination. Building off the Universal Savings Credit proposal, tax provisions should be comparable across savings vehicles—including vehicles for children’s futures—with greater flexibility for savers to decide the purposes that best suit their needs at any point in time. Refundable tax credits can be effective as a way to match contributions to college savings plans, building off the matches that currently exist in 11 states’ plans. And for some families, expanding permitted uses beyond college attendance could boost savings behavior as they anticipate young adults also being able to use funds for homeownership, starting a business, or other needs.

- Congress should stop penalizing college savings. Currently, contributions to college savings plans may make low-income families ineligible for certain types of safety net benefits, such as nutrition assistance, based on the argument that having college savings means they have extra resources that they could devote to immediate needs. This not only discourages contributions and savings, but it also adds administrative complexity and could encourage families facing financial hardship to pay a tax penalty to “cash out” college savings before being eligible to receive safety net benefits. In some circumstances, families may also find that holding 529 assets counts against them for financial aid purposes, which is counterproductive to their intent.

During college: Expanding the American Opportunity Tax Credit and removing barriers

While saving for postsecondary education is critical for families as part of college planning, savings alone will not meet the college expenses for many families. As noted above, a small percentage of families save in 529 plans or Coverdell accounts, and in 2010, the median account balance in these savings vehicles was approximately $15,000. Even after taking into account other forms of savings, such as savings accounts and certificates of deposit, many families lack substantial college savings. Only half of all families with children who plan to attend college are currently saving for higher education in one form or another, according to a recent survey by Sallie Mae, with average savings of $15,000. And low-income savers in the study had average total savings of less than $3,800.

Part of this gap in college affordability is met by Pell Grants and other forms of aid. Pell Grants provide direct federal support to low-income students enrolled in postsecondary education to meet their educational expenses. To be eligible, the student’s parents complete the Free Application for Federal Student Aid, or FAFSA, as early as January for the upcoming academic year that typically begins in August or September but could begin as early as July 1. Pell Grants are paid directly to the educational institution on behalf of the eligible student to meet educational expenses.

The American Opportunity Tax Credit, or AOTC, effectively complements the aid that Pell Grants provide. For each tax year, a taxpayer—the parents of a dependent student or the students themselves—may claim a credit of up to $2,500 for qualified education expenses paid for each eligible student. Unlike a deduction, which reduces the amount of income subject to tax, a credit such as the AOTC directly reduces the tax itself. And 40 percent of the AOTC is refundable, meaning that the credit is paid to the taxpayer even if it exceeds his or her tax liability. The AOTC reaches well into the middle class and is available to single tax filers earning up to $90,000 and joint tax filers earning up to $180,000.

While many families are best served by the AOTC, it isn’t the only tax benefit available during enrollment in postsecondary education, although filers are only able to choose one deduction or credit each year. Single tax filers with incomes below $63,000 and joint filers with incomes below $127,000 can claim the Lifetime Learning Credit instead, a nonrefundable credit for higher education expenses that do not need to be tied to a degree. And for single filers earning under $80,000 and joint filers earning under $160,000, the first $4,000 in tuition and fees is tax deductible.

Taxpayers have found it difficult to correctly choose the tax provision that benefits them the most among the AOTC, Lifetime Learning Credit, and tuition and fees deduction. A taxpayer can only claim the AOTC for a student’s expenses for no more than four tax years, including years when the taxpayer claimed the Hope Scholarship Credit, which the AOTC replaced. There is no limit on the number of years for which a tax filer can claim the Lifetime Learning Credit based on the same student’s expenses, but this credit is less generous. The GAO has found that nearly $800 million in tax benefits went unclaimed in 2009 due to tax filers choosing a less attractive credit, or no credit at all. Even with the help of tax-preparation software or a paid tax preparer, the GAO estimated that about one in six filers did not claim the most advantageous tax provision.

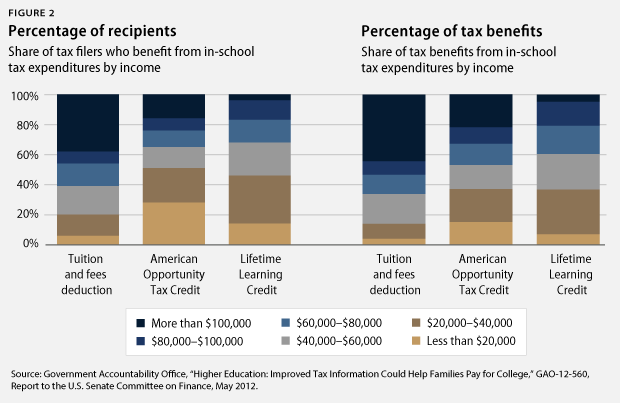

The Lifetime Learning Credit and the AOTC are more progressive than the tuition and fees deduction due to their eligibility limits and their structure as a credit rather than a deduction, as shown in Figure 2. Sixty-eight percent of Lifetime Learning Credit claimants and 65 percent of tax filers who claim the AOTC earn less than $60,000 per year, compared to only 39 percent of filers claiming the tuition and fees deduction. And while nearly half of the tax benefits from the tuition and fees deduction—45 percent—flow to tax filers earning more than $100,000, only 22 percent of the tax benefits from the AOTC and 5 percent of the Lifetime Learning Credit’s benefits flow to tax filers in this income range.

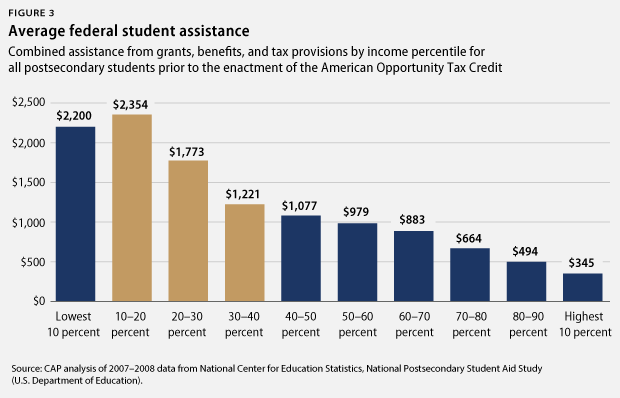

But the structure of the AOTC has historically had limitations as well. Prior to creation of the AOTC, there was a gap in funding between the former Hope Tax Credit and the Pell Grant, which meant that some families did not receive a benefit commensurate with their need. This gap could be clearly seen in data from the 2007-08 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study (Figure 3). Proposals that would reduce the income caps for AOTC eligibility could potentially cause this gap to reappear.

The timing of the AOTC may also be a concern for families struggling to pay for college. While educational expenses are due in August or September, the AOTC is not available until half a year later, when taxes are filed. And by that point, families will be required to pay for the spring semester—even more educational expenses that likely cannot be claimed for an entire additional year.

Again, further action is needed. The following steps would improve tax credits to meet educational expenses.

- The refundable portion of the AOTC should be available in time to meet educational expenses. To be effective in encouraging eligible low- and middle-income students to enroll in postsecondary education, the AOTC needs to be provided in time to meet educational expenses. This typically occurs first in the August after high school graduation.

- The full amount of the AOTC should be refundable. To be effective in encouraging eligible low- and middle-income students to enroll in postsecondary education, the full amount of the AOTC needs to be refundable, up from the current 40 percent. The partial refundability of the AOTC confuses potential students about eligibility and reduces the benefit for low-income students, making college enrollment less likely for those who are the most vulnerable. Refundable credits are most important for families who do not owe federal income tax, but pay payroll taxes and various state and local taxes.

- Duplicative tax credits should be eliminated by adopting the most generous provisions of each. The structure of the tax credits for currently enrolled students is overly complex. As a result, families are required to makes choices among options that are difficult to assess—and frequently choose the option that does not provide the maximum benefit. The AOTC is often the best choice, but the Lifetime Learning Credit is important for adults continuing their education.

- The ban on the AOTC for students with felony drug convictions should be lifted. In addition to meeting certain enrollment criteria to be eligible for the credit, students must not have a felony drug conviction. This provision is unusually invasive and punitive, identifying one particular type of offender who is ineligible for higher education tax benefits while all other criminal offenses are exempt.

After college: Strengthening the student-loan interest deduction and discharge of indebtedness

Historically, the federal tax code has generally maintained that interest should be deductible because to a degree, interest supports some type of investment. Home mortgage interest has long been considered a sacrosanct element of the tax code even though higher-income homeowners, and those with more expensive mortgages, benefit substantially more than middle-class homeowners. Among other types of interest, individuals’ credit card interest was also deductible prior to the Tax Reform Act of 1986, which greatly limited the circumstances where interest is deductible, including student-loan interest.

In 1997, Congress enacted legislation to make student-loan interest deductible once again, as it had been prior to the 1986 tax reform. Initially, interest would be deductible only for the first five years of repayment; this restriction was later lifted. Today, single tax filers earning less than $60,000, and joint tax filers earning less than $125,000, are able to deduct the first $2,500 in student-loan interest paid each year. Borrowers with slightly higher incomes—up to $75,000 for single filers and $145,000 for joint filers—are able to receive a smaller deduction. And unlike the home mortgage interest deduction and many other deductions, borrowers do not need to itemize on their tax returns to benefit from the student-loan interest deduction, making it more accessible to recent graduates.

In practice, the deduction’s effect depends on one’s tax bracket. Single filers earning more than $36,900 who are eligible for the deduction are in the 25 percent tax bracket and can save up to $625 on their federal taxes during the year. Many single filers earning less than $36,900 are in the 15 percent tax bracket, saving up to $375 per year. But others in this income range who are struggling to make ends meet may not have any federal tax liability at all due to other provisions in the tax code, so the deduction does not provide any additional benefit for paying off debt. And the GAO estimates that half of the tax benefits flow to filers earning over $60,000, with 21 percent of benefits going to those earning over $100,000.

The deduction also does not reflect the dramatic increase in student loans over the past two decades. Cumulative student-loan debt increased by 80 percent between 1990 and 2008 for attendees of four-year public institutions and 50 percent for those at private institutions. The average college senior graduated with $29,400 in debt in 2012, and would potentially be able to claim the deduction for much of the 10-year repayment period provided that the income criteria are met. For graduates with incomes that are not commensurate with their debt loads, income-based repayment has become an increasingly popular and often beneficial approach to managing student-loan debt. But these repayment plans involve paying a much greater amount in interest and possibly being able to claim the deduction for as long as 20 or 25 years. Increasing access to and enrollment in income-based repayment may ultimately have positive tax and economic benefits for borrowers, but could also create disincentives to paying down debt more quickly if the deduction is lost as income increases. And borrowers on a standard repayment plan who want to pay down principal and are able to do so are left out of the tax benefits as a smaller share of payments go toward interest over time.

Another side effect of the growth of income-based repayment plans is the potential for large tax bills when graduates’ debt is ultimately forgiven. Other than participants in the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program—which forgives debt balances after 10 years of payments for borrowers working in government, education, or the nonprofit sector—and those in similar programs, beneficiaries of income-based repayment plans are expected to pay taxes on the amount of student debt that is forgiven, based on the presumption that debt forgiveness should be counted as income. This means that after as many as 25 years of reduced payments, borrowers still owe a portion of the forgiven amount, potentially thousands of dollars, when filing taxes.

Taxable discharges also affect disabled borrowers who seek relief. Student-loan debt is nearly impossible to discharge in bankruptcy under current law, which can lead to dire consequences for borrowers who fall on hard times. However, a bankruptcy alternative does exist for a small percentage of borrowers who are permanently disabled and seek a total permanent disability, or TPD, discharge from the Department of Education. Yet, as with other forms of debt discharge, their student-loan forgiveness is immediately reported as income. Borrowers may be able to claim insolvency and avoid taxes and penalties from the IRS, but must apply separately to avoid this tax bill.

Homeownership and other wealth-building opportunities supported by the tax code are increasingly out of reach for highly indebted borrowers. As a result, support for beneficial tax treatment of student loans may be growing as the tax provision that can help them the most. Strengthening the student-loan interest deduction would provide recent graduates with greater spending potential as they struggle to get by and to form households, and would also stimulate the economy.

There are two possibilities for improving the student-loan interest deduction.

- The deduction should be converted into a credit. As a 15 percent credit, higher-income borrowers would not receive a larger tax benefit than lower-income borrowers with lower marginal tax rates, making the treatment of student-loan interest more progressive. If the credit becomes refundable, low-income borrowers who are struggling to make payments would also be able to benefit for the first time. And as a credit, the maximum income cap could also be increased to reach more borrowers and to take into account the growth of highly indebted borrowers, without giving them a disproportionately larger benefit.

- Or, the deduction could be converted into a “payment rebate,” for purposes of simplification and encouraging paying down principal. Generally, interest payments are tax-advantaged while principal payments are not. But with the expansion of income-based repayment, or IBR, plans, this creates a situation where IBR borrowers making smaller payments that largely or entirely go toward interest receive larger tax advantages than borrowers who continue to make the monthly payments under a standard repayment plan and ultimately pay down principal. Without the five-year limit that was initially part of the student-loan interest deduction, this also means that the borrower making payments for 20 or 25 years would receive a substantial tax benefit for a longer period of time. Crediting the total student-loan payments made during the year, at a lower percentage—for example, 5 percent or 10 percent of total student-loan payments up to the current maximum benefit of $675—would effectively treat these borrowers equally and incentivize timely payments rather than simply the payment of interest. A student-loan payment “rebate” would also be easier to administer and more consistent for borrowers and servicers, particularly if it had a higher income cap.

Additionally, further steps should be taken to address concerns with taxable discharges.

- Taxable discharges should be eliminated for all income-based repayment plans. Graduates participating in income-based repayment have greater flexibility in paying off their student loans when faced with high debt loads. After 20 or 25 years, they should not face a substantial—and surprising—tax bill.

- The taxability of disability discharges should be coordinated across the Treasury Department and Education Department. The current process requires borrowers to effectively apply twice for relief—first to the Department of Education for a disability discharge, and then to the IRS to demonstrate that they would be unable to pay the tax bill on forgiven debt. This should be a single, automatic process, not another hurdle for permanently disabled borrowers to navigate.

Conclusion

As tax expenditures increasingly come under scrutiny, policymakers will need to consider which ones work most effectively. Streamlining tax incentives for students, making college savings easier and more rewarding for all families, and supporting borrowers during repayment are all steps that should be components of tax reform to improve access, affordability, and equity in higher education.

Joe Valenti is the Director of Asset Building at the Center for American Progress. David A. Bergeron is the Vice President for Postsecondary Education at the Center. Elizabeth Baylor is the Associate Director for Postsecondary Education at the Center.

The authors would like to thank Harry Stein for his helpful insights and feedback.