For years, federal data essentially ignored the outcomes of the typical community college student. The official Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System (IPEDS) graduation rate counted only students who had enrolled in college for the first time and attended full time. It did not count transfer students or part-time students, even though 65 percent of community college students are transfers, part-time students, or both. And students who took longer than four years to finish school weren’t counted as graduates at all.

Last year, however, the federal government took a big step toward rectifying that with a new set of data called Outcome Measures that includes both part-time and transfer students. This column analyzes how community colleges’ results on the Outcome Measures compared with their IPEDS four-year graduation rate. The new data show that community colleges do a better job supporting their students than the graduation rate has given them credit for.

What the new data reveal about community college students

Community colleges offer an open door to qualified students, and they are a low-cost option for many people to explore their interests and get a taste of college life. That’s why successful outcomes data cannot only include students who earn a credential at the college in which they first enrolled, but also those who transferred to another college. Policymakers, however, have paid little attention to how well that mission is fulfilled, in part because of limitations in the data that were available before the Outcome Measures debuted.

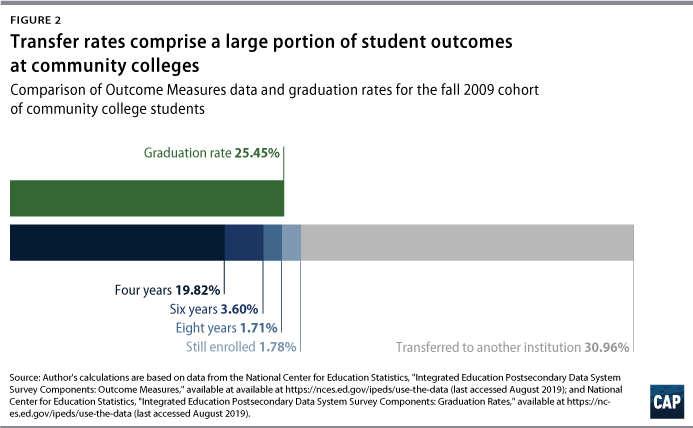

This analysis finds that 30 percent of community college students transfer to another school—far more than the 20 percent of students who graduate from the same institution within four years. To be sure, community college student outcomes remain far from what they should be: More than 40 percent of students neither complete college nor transfer to a different school. The data therefore point to the need for community colleges to improve how they serve their students as well as the need for policymakers to provide community colleges with the funding and support they need to carry out that mission. In addition, because the Outcome Measures still fall short of capturing students’ lived experiences, these results highlight the need for more comprehensive data collection.

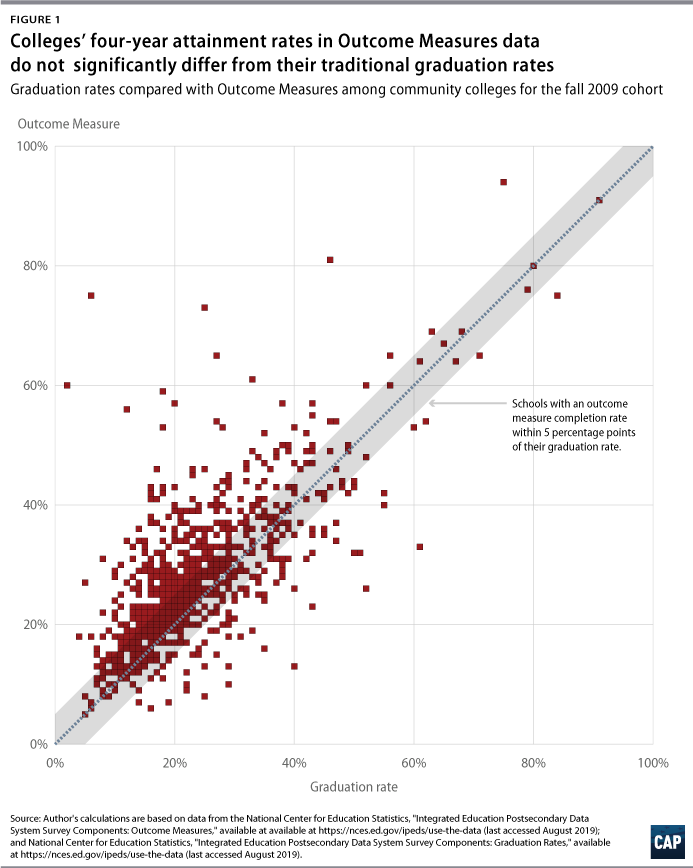

Figure 1 shows how each community college’s traditional IPEDS four-year graduation rate compares with its four-year Outcome Measures completion rate, which includes part-time students and transfer students. A majority of schools have an Outcome Measures completion rate that is within 5 percentage points of their graduation rate. Given that the completion rate includes part-time students, who by definition will take longer to graduate, it is somewhat encouraging to find that the Outcome Measures completion rates are so similar to the IPEDS graduation rate.

Figure 2 shows the range of Outcome Measures results over the course of up to eight years. After the four-year mark, an additional 5.3 percent of students earn a degree within eight years. Most notably, however, a much larger share of students transfers to both four- and two-year institutions than completes their degree. Previously, transfer rates were only available for full-time students entering college for the first time and were measured every three years—clearly missing many students. And many schools didn’t report their transfer rates at all.

Unfortunately, the data don’t show what proportion of transfer students go on to complete their degree, and transfer data are only available at the eight-year mark. Without knowing what happens to students after they transfer, it’s impossible to assess whether or not they ultimately completed their degree.

Other significant blind spots remain in the Outcome Measures data. The data identify students as either part-time or full-time based on their first semester of enrollment in the school. But the enrollment pattern of many community college students is highly variable; they could be part-time during the fall semester while juggling multiple jobs, but they may choose to enroll in school full time during the spring semester.

Proposals to help community colleges succeed

The College Transparency Act, introduced in 2019, would help researchers and policymakers answer important questions by tracking students over the course of their education rather than taking limited snapshots when they arrived at or leave a given institution. It’s long been known that community colleges struggle with college completion more than four-year colleges, and there are a variety of factors at play: Community colleges receive much less state funding than four-year colleges, and their student population is more likely to be balancing other priorities such as caring for children or working long hours as well as to be placed in remedial classes that slow their path to a degree.

One solution would be to provide more funding for these schools while also addressing problems that prevent students from completing their degree, such as food insecurity, housing instability, and transportation issues. Beyond Tuition—the Center for American Progress’ plan for addressing affordability, accountability, and equity in the United States’ higher education system—calls for a major investment from state and federal governments in public higher education, which includes community colleges. Community colleges enroll a large share of low-income students and students of color, so investing in these institutions would be a powerful step toward reducing societal inequities.

Administrators of community colleges also need to think about how to redesign their programs to address the needs of nontraditional students. Bunker Hill Community College in Boston, for example, is doing just that in designing learning communities with part-time students in mind.

Community colleges are doing better than they have been given credit for. State and federal government—along with college administrators—must continuously invest in community college students to ultimately help them succeed in school and beyond.

Victoria Yuen is a policy analyst for Postsecondary Education at the Center for American Progress.

*Author’s note: The data are representative of 85 percent of all community colleges in the IPEDS. Schools without complete data were deleted from the sample.