As the Trump administration’s approach to North Korea appears to shift back and forth between saber rattling and hints of diplomacy—with leading administration officials at times sending contradictory signals—it is clear that the administration needs an overarching strategy for addressing the North Korean threat.

That strategy must include a tough, smart, and carefully targeted sanctions offensive. However, given President Donald Trump’s fiery exchanges with Kim Jong Un, and the drumbeat of White House statements and media opinion pieces discussing potentially imminent military action, one can be forgiven for having the impression that the United States has already run its best sanction plays against North Korea. In reality, that effort has only just begun, and if the United States can stay the course, it has the potential to turn this crisis around.

Chinese diplomats often claim that it is pointless for China to cut off its economic ties with North Korea because Kim Jong Un would rather let his people starve than give up his nuclear program.1 They give an impression that there is no middle ground: If China pushes North Korea economically, the regime will resist until it collapses, triggering a massive security crisis on the Korean Peninsula.2

There is an equal amount of hand-wringing on the U.S. side. American observers tend to view the past decade of apparently ineffective U.N. action as evidence that sanctions are a dead end and military action will eventually become inevitable.

In truth, there is a middle road on sanctions and it runs in two directions: through China and through North Korea’s gateways to the international financial system. The reality is that North Korea is much more exposed than many observers recognize, and the United States has only just begun to target the regime’s biggest weak spots. Instead of blowing hot and cold with China and exchanging blustery rhetoric with North Korea—two approaches that give China maneuvering room to avoid action—the United States needs to double down on a strategy that deals an economic blow against North Korea on par with the blow that brought Iran to the negotiation table in 2013.3

Such a strategy should be rooted in six critical factors—each of which highlights realities that are often overlooked when considering North Korea and its relationship with China.

- North Korea’s urban elites are Kim Jong Un’s new weak spot.

- North Korea is more exposed to U.S. and global financial systems—and thus more vulnerable to U.S. and international sanctions—than many observers realize.

- China owns the North Korea problem in ways that the international community has thus far failed to exploit.

- China is profiting from its gatekeeper role in ways that the international community has largely ignored.

- Existing sanctions primarily aim to block North Korean exports, but imports are the regime’s bigger vulnerability.

- The United States has yet to fully exploit a number of powerful tools available for action against both China and North Korea.

These factors point toward a sanctions strategy that—when implemented effectively and paired with diplomatic and military tools—could strongly encourage North Korea to halt and eventually begin rolling back its nuclear and missile programs. To succeed, the United States must truly cut off North Korea’s access to the international financial system and show China—for the first time—that there will be real costs if it does not implement U.N. Security Council resolutions.

Urban elites are a new weak spot for Kim Jong Un

Economic growth is picking up speed in North Korea, creating a weakness that the international community has yet to fully exploit.

Last year, the North Korean economy grew 5 percent, the nation’s biggest economic jump since the 1990s.4 Its external trade also grew around 5 percent.5 Under Kim Jong Un’s leadership, the country’s urban elites—high-ranking officials, military leaders, and politically connected business leaders—are doing particularly well.6 They attend university; buy home goods at international retailer Miniso’s new Pyongyang shop; drink black-market Coca-Cola; drive Audis; and use cell phones imported from China.7 They enjoy a rather comfortable lifestyle and—as in other authoritarian regimes—they support the current regime, in part, because they have much to lose if it falls.

These elites are Kim Jong Un’s new weak spot. He is increasingly dependent on private enterprise to drive economic growth.8 By allowing the people who control the levers of commerce to grow wealthy, he keeps them invested in his regime. However, if that relationship is disrupted—for example, if sanctions cut off North Korea’s access to the goods and trading systems that urban elites depend on to build wealth—the nation’s new commercial class will have less to lose if the current regime falls. They also have more to gain by pressing Kim to enter into negotiations for sanctions relief.

North Korean defector and former diplomat Thae Yong Ho claims the nation’s elites are already experiencing “disillusionment” with Kim Jong Un.9 That may or may not be the case at present; elites do appear to be doing well under the current system. However, driving a wedge between Kim and the elites on whom he increasingly depends should be a key strategic objective. To be sure, it is highly unlikely that rising dissatisfaction among North Korea’s urban elites will substantially undercut regime stability in the near term. Kim Jong Un still controls the nation’s security apparatus and has demonstrated a willingness to respond ruthlessly to potential political challenges. However, a combination of coercion and reward is more effective than coercion alone. Sanctions that substantially reduce his ability to reward political supporters will make him more vulnerable, and that vulnerability could pull him toward negotiation.

The targeting of elites has worked well in other cases: It played a critical role in bringing Iran to the negotiation table in 2013.10 In North Korea, the emergence of an elite commercial class is a relatively new phenomenon. As the international community struggles for leverage over North Korea, this opportunity should not be overlooked.

North Korea is exposed to U.S. and global financial systems

North Korea is often described as a “hermit kingdom,” cut off from the outside world and thus hard to influence.11 The reality is more nuanced and complex.

North Korea depends on international markets to source key components for its weapons programs and foreign goods for its urban elites. Those transactions run through a series of front companies. North Korea sends domestically produced goods out to front companies who sell those goods abroad; generate cash in U.S. dollars and other foreign currency; and use that cash to purchase goods that North Korea cannot produce at home.12 Critically, the overseas entities that buy from North Korea are different from those that sell to it. That means that North Korea must run cross-border financial transactions, which opens up a tremendous vulnerability that the United States has only just begun to exploit.

The Center for Advanced Defense Studies (C4ADS), a U.S. nongovernmental organization that specializes in mapping illicit trading networks, tracked North Korea’s cross-border exchanges and discovered that its front companies often disguise these transactions as legitimate commercial activities. These activities are run through global financial systems, including U.S. companies and banks.13 North Korea depends on a relatively small number of trusted international companies and individuals to provide gateways to U.S. and international financial systems. These companies are generally large-scale international trading firms that nest North Korean trading activities within a much broader array of licit activities.14 That makes them more valuable and much harder to replace than the multitude of small and shady front companies capable of transferring goods and cash across the Chinese border. C4ADS mapping suggests the gateway entities—some of which can be identified through open source data mapping—are key “chokepoints” that, if successfully targeted and blocked via U.S. or international sanctions, could potentially disable North Korea’s entire overseas trading system.15

The United States has the ability to take unilateral action against these chokepoints. If the United States has evidence that third-party gateway firms are facilitating North Korean transactions that violate existing sanctions, the U.S. Treasury Department can block those firms from accessing the U.S. financial system. The amount of North Korean money running through the United States is surprisingly large. A recent U.S. Department of Justice investigation discovered that one North Korean gateway company—Dandong Hongxiang Industrial Development Co. Ltd.—used shell companies to run transactions of more than $70 million through the U.S. financial system.16

North Korea cannot supply its weapons programs or keep its urban elites happy without running money through international markets, particularly U.S. markets. It is high time for the United States to take full advantage of that vulnerability.

Washington is finally taking steps in that direction. In July 2017, the U.S. Congress passed the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act, which calls on the executive branch to take action against third-party entities who transfer cash or otherwise assist North Korea in transactions that violate U.N. sanctions.17 On August 22, the U.S. Department of the Treasury sanctioned six individuals and 10 companies that appeared to operate as chokepoints or shell companies for North Korea.18 One of the targeted companies—Dandong Zhicheng Metallic Material Co. Ltd.—appears to be a critical gateway that Pyongyang uses to access overseas bank accounts.19 This is good progress, but the United States should move quickly to box in more of Pyongyang’s financial chokepoints. If sanctions progress in a slow, step-by-step manner, North Korea can reroute transactions to nonsanctioned gateway firms. If the United States uses targeted unilateral sanctions to box in a large group of these critical nodes simultaneously, it will deliver a much more destabilizing blow. Given the recent pace of North Korean military provocation, a blow of that magnitude is clearly overdue.

China owns the North Korea problem

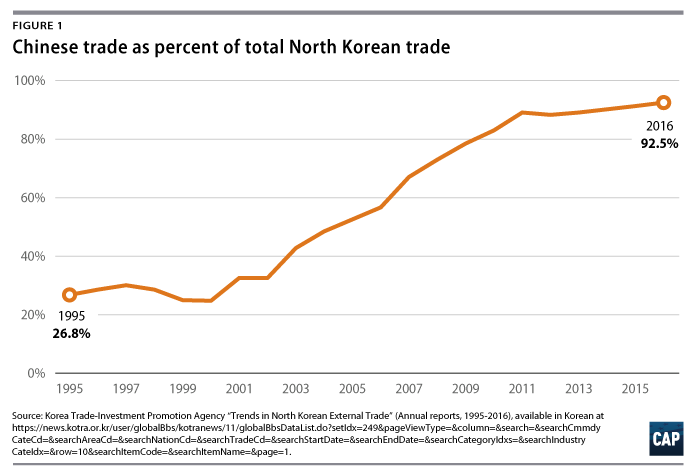

In 2006, around 56 percent of North Korea’s external trade went through China.20 Today, at least 90 percent of North Korea’s trade goes through China.21 Ten years of international sanctions, combined with 10 years of weak Chinese implementation, have pushed North Korea into an unprecedented reliance on China. This new relationship creates new opportunities for action against both nations.22

Chinese leaders are playing a double game: Beijing first signs on to United Nations sanctions aimed at restricting North Korean access to cash and weapons; then, as other U.N. member nations implement those sanctions, it allows Chinese individuals and enterprises to move in and take over the abandoned supply routes. Chinese entities are enabling North Korea to circumvent U.N. sanctions through multiple channels by:

- Adding “livelihood exemptions” that allow firms to self-declare that their transactions are “for the people’s livelihood” and unrelated to North Korea’s weapons programs; the Chinese entities then leverage this loophole to continue trading banned goods.23 In 2016, China imported $60 million in iron ore from North Korea under a livelihood exemption.24

- Using their own narrow interpretation of sanctioned goods categories to ship prohibited items to North Korea. In 2015, Chinese officials allowed a Beijing-based company to import aircraft from New Zealand and Italy—two nations that consider aircraft a sanctioned luxury good—and then send it onward to North Korea. When confronted, Chinese officials claimed they define luxury goods differently than do other member states.25

- Allowing North Korean individuals and entities—including some with direct, traceable links to the nation’s nuclear program—to set up front companies in Beijing and run prohibited minerals from North Korea to China and then onward to third-country buyers.26

- Allowing Chinese companies to import rocket components, drones, and other commercially procurable military equipment from third-party nations and then send that equipment onward to North Korea.27

- Allowing Chinese companies to import military equipment from North Korea and then sell it to third-party countries to generate cash for the North Korean regime.28

It is time for the international community to hold Chinese leaders accountable for violating sanctions that their own diplomats signed on to. Chinese leaders want their nation to be viewed as a responsible power—that is why they signed on to those sanctions in the first place. At a bare minimum, the United States and its partners should be doing much more to hold China accountable for implementing those measures.

Beijing also has a clear responsibility to provide the international community with detailed, real-time information about China-North Korea trade flows. Crude oil appears to be North Korea’s largest import from China, but China stopped reporting crude oil shipments in 2014.29 That is unacceptable. As North Korea’s gateway to the world—for both sanctioned and non-sanctioned goods—China bears responsibility for monitoring and reporting on the nation’s trade activity.

China is profiting from its gatekeeper role in ways that have been ignored

When Chinese officials and foreign policy experts discuss the nation’s reluctance to impose new economic sanctions against North Korea, they often frame its position as one of responsibility and caution. In reality, China has an array of national interests tied up in its trade relationship with North Korea. Some Chinese provinces and businesses are profiting from bringing the region to the brink of nuclear war, and those profits play a role in Bejing’s reluctance to cut off trade.

Two Chinese provinces share a border with North Korea: Liaoning and Jilin. Economically, they are among China’s worst-performing provinces, and Beijing has long framed Sino-North Korean trade as the border area’s path to prosperity.30 In 2007, China’s State Council—the national cabinet—issued a northeast region revitalization plan that calls for more investment in cross-border trade with North Korea.31 Specifically, the plan orders northeastern provinces to “promote the construction of roads, sea ports, trade posts, and economic cooperation zones with Russia, Mongolia, and North Korea” and pour money into the additional infrastructure needed to move goods between those border areas and other parts of China.32 These infrastructure investments played a key role in the subsequent expansion of China-North Korean trade.

If that strategy has changed, China’s border regions have not yet received the memo. Most China-North Korea trade flows through Dandong City in Liaoning province. The city’s implementation guidelines for the 13th five-year development plan (2016–2020) include instructions to speed construction of the China-North Korea border trade zone to “increase the level of trade with North Korea” and “expand the scope of trade with North Korea.”33 If Beijing has amended those development guidelines in 2017—or forced Dandong City to do so—that information has not been made public.

Beijing is sending different messages to different audiences on North Korea. When Chinese leaders face the United States and the international community, they talk about acting responsibly to avoid triggering a disaster on the Korean Peninsula. Yet when they talk to North Korea and their own northeastern provinces, they talk about economic opportunity. The message Beijing sends with its actions is that China does not want to be seen as an irresponsible nation internationally, but it values economic cooperation with North Korea more than it fears the security threat that North Korea’s nuclear program presents.

As of September 2017, Beijing is at least leaning toward putting regional security over economic gain. Beijing supported the August 2017 U.N. sanctions and appears to be putting more effort into implementation than before. Early signs suggest that trade with North Korea is dropping. Chinese police appear to be cracking down on cross-border seafood smuggling,34 and Chinese businesses in Dandong City are grumbling that trade “has all pretty much slowed.”35 At the same time, however, on August 10—shortly after the new sanctions were issued—the Shanxi government in northern China announced a new charter flight service that includes a direct flight from Datong to Pyongyang every five days.36

China wants the international community to treat it as a major power. Yet, when it comes to trade with North Korea, Beijing has turned its back on responsibility and acted instead as if enabling a rogue nation does not merit consequences. It is time to confront China with that inconsistency.

Existing sanctions not targeting North Korea’s import vulnerability

Since 2006, U.N. sanctions against North Korea have expanded from banning specific weapon components to banning broader dual-use technologies and, starting in 2016, broader categories of commodities that the regime sells abroad to generate cash for its weapons programs.37 However, U.N. sanctions do not yet target a broad array of North Korean imports, and that is currently one of the regime’s most significant weak spots.

North Korea’s economy and weapons-development programs are still dependent on foreign technologies and foreign luxury goods. U.N. sanctions have attempted to restrict North Korea’s access to those goods by making it harder for the regime to acquire weapons components and sell commodities abroad.38 So far, there have been seven U.N. sanction resolutions against North Korea. The first—resolution 1695 passed in 2006—only covered missile-related goods and technologies. Two of the next three sanction packages—U.N. resolutions 1718, 1874, and 2094, passed respectively in 2006, 2009, and 2013—also cover luxury goods. In 2016, with U.N. resolutions 2270 and 2321, the United Nations also began blocking North Korean mineral exports. And in 2017, with resolution 2371, the United Nations expanded that export ban to also cover coal, seafood, and labor. These U.N. sanctions only apply to the entities or individuals specifically designated under each resolution; it is up to each U.N. member state to implement the measures.

What the U.N. has not yet done is directly ban other nations from selling a broad array of nonmilitary goods to North Korea. This should be the next step. Last year, China’s reported exports to North Korea exceeded $3.4 billion.39 Those trade flows provide a road map for targeting goods that the regime cannot produce domestically, with crude oil, computers, and video displays high on the list. North Korea must go through layer upon layer of shell companies to sell commodities abroad and generate cash to import these goods. They would not be doing so if the regime did not view those imports as a critical need.

If the international community can successfully implement existing sanctions—which focus primarily on North Korea’s weapons imports and commodity exports—it will make it harder for the regime to raise cash abroad. However, North Korea likely has access to at least some cash stockpiles that it can use to finance purchases for a period of time. If sanctions target the goods North Korea is currently purchasing, they will hit the regime from both sides and substantially raise the costs associated with the nation’s current military trajectory.

The United States has powerful tools in its arsenal

The factors outlined above point toward three types of sanctions that are likely to be particularly effective in targeting the flow of goods and capital that North Korea currently depends on to keep its economy growing and its weapons programs advancing. These measures include:

- Secondary sanctions targeting large-scale, third-country, gateway firms that North Korea relies on to access the international financial system. These firms are engaged in a broad array of licit international transactions, some of which run through U.S. financial systems. For these firms, North Korean money laundering is a small part of a much larger business operation, and although the illicit transactions are profitable, they are generally not profitable enough to risk bringing down the firm’s licit businesses. That makes these firms soft targets for unilateral sanctions and hard for North Korea to replace. If the United States starts sanctioning third-country gateway firms on a broad scale, remaining nonsanctioned firms will have an incentive to either drop their own existing North Korean money laundering operations or say “no” if North Korea approaches them to replace sanctioned gateways. This could lead North Korea’s entire international trading system to implode.40

- New U.N. sanctions that block a broad array of North Korean imports. Thus far, U.N. sanctions on North Korean imports only limit military technologies and some luxury goods. Imports are ripe for further exploitation. The next round of U.N. sanctions should target imports that supply the nation’s technology needs and a much broader array of luxury goods supplying the nation’s urban elites.

- Secondary sanctions targeting Chinese individuals and entities that violate existing U.N. sanctions. China is North Korea’s biggest trade gateway. Beijing signs on to multilateral sanctions and then turns a blind eye when Chinese companies shuttle sanctioned goods, including weapon components, back and forth across the China-North Korea border. The United States has been treating China as a partner in its effort to contain the North Korean nuclear threat. It is time to base China’s role in that effort on China’s actions. By enabling North Korean weapons development, China has thus far been part of the problem, not the solution. The best way for the United States to make this clear is with unilateral secondary sanctions against China. If China cracks down on cross-border trade and behaves as a true partner in this crisis, the United States can relax its sanctions against Chinese entities. And if China continues to help North Korea circumvent U.N. action, the United States should impose more sanctions against Chinese entities.

Simultaneously, the United States must also step up its diplomatic game with Beijing. Specifically, the United States should:

- Be willing to have a contentious U.S.-China relationship, including at the presidential level. President Trump appears to be more comfortable issuing strong threats via Twitter than in person. That is a problem. The president of the United States must be willing and able to apply pressure on his Chinese counterpart. The Obama administration’s approach with China over cyberespionage offers an excellent playbook for leveraging a combination of presidential-level retaliatory threats and diplomatic embarrassment in order to hold Beijing accountable for adhering to international norms.

- Determine which sanction targets will hit North Korea the hardest when implementing existing U.N. sanctions and bring that list to Beijing for near-term implementation.

- Demand—in collaboration with multilateral partners—that China provide detailed, real-time information about China-North Korea trade flows, including crude oil shipments.

- Use actual shifts in those trade flows as a metric to determine whether China is upholding its implementation responsibilities and if more sanctions are needed against both North Korea and China

- Hold China responsible for policing its borders to ensure that improved sanctions implementation does not simply push Sino-North Korean trade to alternate transport routes, again in collaboration with multilateral partners.

The 2017 Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act gives the executive branch broad authority to move on every action item outlined above. In any presidential administration, executive branch agencies are generally hesitant to take actions of this nature—particularly secondary sanctions against third-party nations—due to the risk that the diplomatic fallout could make it harder to advance other initiatives. Thus far, the Trump administration has been particularly reluctant to take action against China.

At the presidential level, President Trump’s rhetoric blows hot and cold. He is prone to issuing verbal threats against China without follow-through, as well as statements of appeasement that do not match China’s actions and do not appear to further American interests. The president’s June 20, 2017, statement is particularly concerning. Despite the clear pattern of Chinese sanction violations, outlined above, he issued a tweet stating: “While I greatly appreciate the efforts of President Xi and China to help with North Korea, it has not worked out. At least I know China tried!”41 That suggests Beijing has done everything it can, when the evidence suggests the opposite is true. Based on President Trump’s back-and-forth signaling thus far, Chinese leaders would be justified in assuming that current U.S. retaliatory threats are largely bluff. That assumption would encourage China to put on a show of implementation without substantially changing its policies toward North Korea.

It is highly unlikely that the Trump administration will be able to turn this problem around without strong congressional leadership. There are extraordinary civil servant experts on China and North Korea that are working across the executive branch, but their ability to manage up at the presidential level is severely limited. Only the U.S. Congress can play that role.

The U.S. Congress can provide much-needed leadership in three critical areas:

- Require the executive branch to set clear near- and medium-term parameters for determining whether China is making sufficient progress to curtail sanction violations occurring within its own territory.

- Require the executive branch to prepare a battery of secondary sanctions against key North Korean financial chokepoints and Chinese sanction violators. The July 2017 Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act gives the executive branch six months to report on third-party entities violating existing sanctions against North Korea. Given the pace of North Korean provocation, that timeline should be shortened. If China and North Korea do not meet U.S. deadlines for positive action, more sanctions should be issued. If that round does not produce change, the United States should be ready with another round. The pace of sanctions must match the pace of North Korean weapons advancements and provocation. Progress should be assessed—and retaliatory actions taken—on a monthly basis.

- Credibly signal to both North Korea and China that the United States is launching a new sanction strategy and will steadily ratchet up the pressure on both nations if there is no forward movement. Unfortunately, President Trump’s back-and-forth rhetoric has substantially eroded White House credibility on this issue. Congress can help fill the gap.

Looking forward, if a tough and targeted sanctions strategy convinces Kim Jong Un to enter some form of multilateral negotiations over his weapons program, congressional leadership will also be needed to guide that process. If negotiations do commence, both China and North Korea will be angling to entangle the United States in a long, drawn-out process in which the United States and other U.N. member nations quickly ease sanction pressure in exchange for minimum concessions from North Korea. Congressional oversight can play a critical role in keeping the White House from jumping at a bad deal that brings short-term domestic political gain but poses grave dangers to U.S. national security over the longer term.

It is important to remember that the United States is not facing a binary decision between “deal” and “war.” If the only deal North Korea is willing to offer is a bad one, then the United States may be better off boxing North Korea in with a combination of military deterrence and economic sanctions. The end goal is to reduce the security risk North Korea poses to the United States, its allies, and the Asia-Pacific region. The United States must remain unswerving in its pursuit of that objective.

Melanie Hart is a senior fellow and director of China Policy at the Center for American Progress. Renee Ding is an intern at the Center.

The authors would like to thank Blaine Johnson, a policy analyst for China and Asia Policy at American Progress, and Abby Bard, a research assistant for Asia Policy at the Center.