This summer, President Donald Trump’s secretary of agriculture, Sonny Perdue, signed a memorandum of understanding with Alaskan officials to rewrite the federal roadless rule that, among other provisions, limits road construction in national forests.1 With the October 15 closure of the initial comment period on the proposed rule change looming, Alaska is a step closer to ushering in potentially major changes for the Tongass, the nation’s largest national forest, including opening millions of acres of public lands to logging and road construction.2

First implemented in 2001, the roadless rule prohibits the construction or expansion of roads on certain tracts of undeveloped land in national forests. The rule aims to protect sensitive habitats and wild areas, as well as to conserve natural resources—an obligation that is part of the U.S. Forest Service’s (USFS) mandate to manage public land for multiple uses.3 The rule has been especially contentious in the Tongass National Forest, because it reflects a shift from the long history of subsidized logging of the Tongass’ old-growth forests and toward a more sustainable management approach that capitalizes on the region’s globally unique ecology.

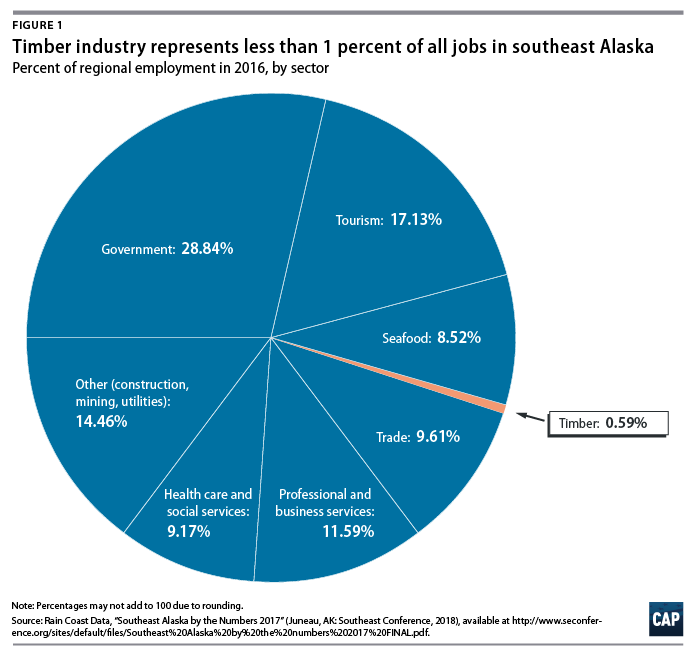

The Trump administration’s proposed change to the roadless rule is just the most recent example of the USFS’ reliance on an antiquated strategy: managing the Tongass for timber, an industry that accounts for not even 1 percent—less than 400—of southeast Alaska’s jobs. More profitable industries, on the other hand, such as tourism and commercial fishing, together generate more than $2 billion in revenue annually and employ more than 10,000 people in the region.4 The Trump administration’s move to expand logging in the Tongass follows decades of the federal government subsidizing timber sales in the national forest, often to the tune of more than $20 million per year.5 These subsidies became news yet again this summer when a controversial southeast Alaska timber sale, promoted heavily by the USFS, received no bids, despite significant federal subsidies that included USFS investments of $3.1 million in new roads.6 Despite the expense to taxpayers, the USFS estimated the sale would generate just $200,000 in revenue.

The situation underscores how focusing on timber production in the Tongass wastes vast amounts of taxpayer money in pursuit of limited returns. At the same time, this timber-centric approach neglects the opportunities that the Tongass creates for other industries, namely commercial fisheries and tourism, which, as noted earlier, are cornerstones of southeast Alaska’s regional economy.

Tongass 101

Established in 1907, the Tongass National Forest is the nation’s largest national forest covering almost 17 million acres of islands and mountains in southeastern Alaska.7 Much of the land in the Tongass is exposed rock and ice, but roughly 9.7 million acres are forested—stands of mossy conifers growing along the coast and up the lower slopes of mountains.8

The Tongass is part of the largest temperate rainforest in the world, which stretches from northwestern Oregon to south-central Alaska.9 Unlike other parts of the forest farther south, areas near the Tongass are sparsely populated and, as a result, relatively intact compared with elsewhere in the Pacific Northwest. However, the impact of decades of intensive logging and mining are still evident in many parts of the landscape.10

Importantly, the forest provides rare ecological values, including thousands of miles of streams that provide critical spawning habitat for salmon, that are found only in natural areas with little human disturbance. Across most of North America, these types of spawning streams have been altered by logging and development, but the Tongass still supports some of the healthiest salmon runs in North America with populations close to their historical levels.11 Moreover, the large stands of old-growth forest also retain more carbon than any other forest type in the world, including tropical rainforests, which is critically important for future efforts to address climate change.12

The bad economics of logging Tongass’ old-growth forests

In the mid-20th century, the federal government provided massive subsidies for logging in the Tongass in an attempt to advance economic development in southeast Alaska. This approach was in line with the focus on timber production that guided USFS practices at the time.13 The federal government signed 50-year contracts with two companies to harvest 13.5 billion board feet of timber for pulp.14 The equivalent of logging as many as 1.7 million acres, these sales led to investments in two large processing facilities in the region. However, the low fees that the USFS collected from the timber companies for these projects meant that public spending to prepare these harvests far exceeded revenues, even as thousands of acres of old-growth forest were clear-cut.15

By the 1990s, the economic realities of subsidizing timber harvests in the Tongass had become clear. Decades of logging had not generated significant local employment to justify the disturbances that were being made to the forest. The two large contracts were ended in the mid-1990s, followed by closures of the two mills they had supplied.16 At the same time, the health of the regional economy hinged increasingly on the commercial fishing industry and a growing tourism industry, drawn to the region by cruises, sport fishing, and other outdoor recreation opportunities that rely on a natural, undisturbed Tongass.

How attempts to effect lasting change fell short

Congress passed the Tongass Timber Reform Act in 1990 to shift toward a more balanced approach to forest management that builds on the comparative economic advantages the Tongass provides. This approach included decadal budgets for timber harvest—capping the number of board feet that could be harvested over a 10-year period—as well as limits on logging near salmon streams. In addition, a new land management plan was adopted in 1997 that directed a shift away from old-growth logging to instead harvest second-growth timber on sites where old-growth forests had previously been logged.17 The shift in management strategies continued in 2001 when the roadless rule took effect, providing protections for 9.5 million acres of the Tongass.18

In 2010, then-Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack announced the Tongass Transition Plan, a framework for directing greater support from USFS and other U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) agencies to industries that anchor the region’s economy, especially recreation and commercial fishing.19 This was followed by a 2013 memorandum directing a shift away from old-growth logging and toward harvesting in younger stands.20

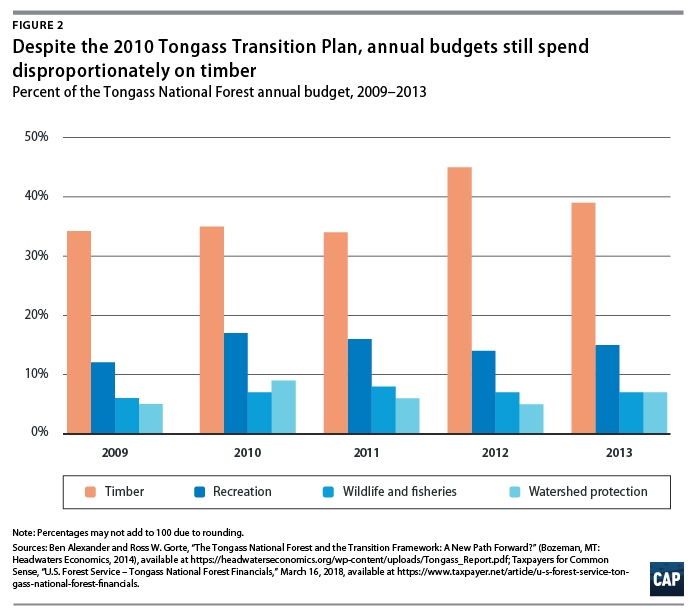

Despite these attempts to transition the management of the Tongass away from a focus on old-growth timber harvest, the timber lobby and the state of Alaska have continued to advocate for logging, and timber and road projects have remained a significant portion of the Tongass National Forest budget.21

A 2014 analysis of budget data by the nonprofit research organization Headwaters Economics revealed that, despite the launch of the 2010 transition plan, line items related to timber sales and harvests comprised at least 34 percent of the annual budget for the Tongass between fiscal years 2009 and 2013, and staffing for timber-related activities remained near 30 percent of all employees.22 (see Figure 2) Meanwhile, funding and staffing for the programs that support commercial fishing and tourism, including watershed management, trail maintenance, and wildlife and fisheries programs, remained constant at relatively low levels—less than 30 percent combined—despite their relative importance to the region’s economy and the USFS’s commitment to a transition.23

At the same time, the receipts from timber sales on the Tongass were far below levels that typically justify investment. Records obtained by Taxpayers for Common Sense reveal that while the federal government spent an average of $23.1 million annually between fiscal years 2009 and 2013 to manage timber sales, the USFS timber program in the Tongass ran an average annual net loss of $21.75 million and never lost less than $15 million in any year due to the low USFS fees and poor timber sales.24

This stretch of continuous losses reflects the dedication to logging by the state and the timber industry, which has persisted despite clear economic realities. For decades, high harvesting costs and low timber prices have meant that the Tongass acts as a so-called last in, first out supplier for wood products markets in the western United States, providing material only when market demand is very high.25 This lack of consistency means the USFS cannot sell enough timber to meet its production goals—despite federal subsidies and occasionally dubious sale practices—and runs counter to the argument that the USFS’ focus on timber is a reasonable approach to the region’s economic needs.

In 2016, the USFS released an updated land management plan for the Tongass National Forest, which formalized a management trajectory to complete the transition from old-growth logging to the more economically viable aspects of the local economy.26 Although the plan includes important conservation measures for salmon streams as well as other provisions to support fishing and tourism, since being finalized, it has been in the crosshairs of Alaska’s congressional delegation, which has introduced legislation to repeal the plan on multiple occasions.27

Meanwhile, the USFS has continued to prepare old-growth timber sales. Most recently, it has attempted sales for old-growth timber on the uninhabited Kuiu Island on multiple occasions but have thus far received no bids.28 The timber sale lies in an area of Kuiu that contains one of the most important watersheds for salmon production in the Tongass.29 Despite the fact that the sale is only estimated to generate $200,000, the agency is planning the construction of a $3.1 million road to access the site. In addition, the USFS has already granted a waiver to allow timber logged on Kuiu to be exported to mills overseas for processing immediately following harvest.30 This waiver applies to rules meant to support U.S. timber jobs. These rules are in place for every national forest but are often waived for timber sales in the Tongass to attract logging companies. Timber logged in the Tongass won’t sell without the waiver, because high costs of harvest and low demand make it unprofitable to harvest and process the timber within the United States. Moreover, exporting timber creates only limited local jobs through logging, while the added employment created by mills is largely developed outside the United States.

In addition to its efforts on Kuiu, the USFS has drawn criticism for other recent timber sales in the Tongass. In 2017, environmental groups filed suit over concern that the agency had overestimated the available timber in the Big Thorne timber sale by 12 million board feet—roughly equivalent to about 1,500 acres of Tongass forest.31 USFS is also facing allegations of mishandling its appraisals and review processes, allowing timber companies to harvest high-value tree species but charging rates equal to those for the harvest of low-value species.32

What a true transition toward sustainable forest management would look like

Instead of focusing on the empty promise of old-growth logging, Agriculture Secretary Perdue and the USFS should make real investments in the types of forest management that are cost-effective and proven to support the economy of the southeast Alaska region.

Although the Tongass has relatively low levels of watershed degradation compared with other parts of the country, investment in forest and stream restoration would greatly benefit the fisheries that rely on forest health and, in turn, support the regional economy.33 In 2017, king salmon fisheries in southeast Alaska were forced to close temporarily, as the fish population dropped to its lowest numbers since 1975.34 While the cause of the declines is unclear, more logging and road construction in spawning habitat would create additional stress. Salmon species comprise half the earnings of a seafood industry that generates nearly $1 billion in annual economic activity for the region; subsidizing logging and construction efforts that would threaten these species is not a sound investment.35 Despite committing to an increase in funding for stream restoration in previously logged areas and where logging roads abut or cross salmon streams, the USFS has yet to follow through on this $100 million backlog of projects.36

Moreover, investments in regional fisheries should extend beyond the health of salmon streams. The USDA’s Office of Rural Development has provided some grants to expand or renovate seafood processing plants, and other financial support could help expand aquaculture operations near communities to diversify the seafood industry.37

Recreation and tourism should also receive greater investment and support. It is estimated that outdoor recreation supports roughly 72,000 jobs in Alaska—more than oil, gas, mining, and logging, which together support just 15,000.38 The Tongass, and southeast Alaska more generally, play a key role in the health of the state’s tourism industry, as cruise lines bring visitors to fish, hike, and explore the region’s cultural and natural history.39 Investments in tourism infrastructure, including cabins, trails, and facilities for cruises, would have a much greater economic impact than logging.

That said, there is still some opportunity for timber production in the Tongass but not in places with high-value salmon habitat or where the roadless rule has protected old-growth trees. The USFS recently approved one such project on Wrangell Island.40 It includes the harvest of younger-growth trees, with a focus on production to meet local and regional demand. This type of project should be a priority for the USFS; it supports timber jobs and the region’s small mills, as well as compensates, in part, for the impacts of past logging projects on the forest landscape, creating spillover benefits for the region’s ecology and economy.

Another positive step is the USFS’ commitment to use local wood products for tourism infrastructure such as cabins, and to work with the Rural Development Office and local businesses to develop processing capacity for small-diameter logs.41 These objectives—and investment in projects that complement existing tourism operations, such as trail infrastructure and support for private guide businesses—are much more likely to generate a return than any old-growth sales.

Conclusion

The past three decades of economic development in southeast Alaska provide clear evidence of the importance of recreation, tourism, and fisheries to the health of the region and its economy. And while Agriculture Secretary Perdue suggests that timber and these more successful industries in southeast Alaska are not “mutually-exclusive,” the USFS appears to remain committed to pursuing antiquated timber practices—including federal subsidies for old-growth logging that have failed for decades to prop up the timber industry, rather than finding a balanced approach to grow the regional economy.42

After years of favoring timber over more productive industries, federal agencies and Alaska’s representatives should acknowledge the writing on the wall. Instead of pursuing a flawed revision to the roadless rule, they should work to direct federal investments to the proven approaches that draw on the real values of the Tongass National Forest to support local communities.

Ryan Richards is a senior policy analyst for Public Lands at the Center for American Progress.

The author would like to thank Matt Lee-Ashley, Sally Hardin, and Jenny Rowland for their contributions to this issue brief.