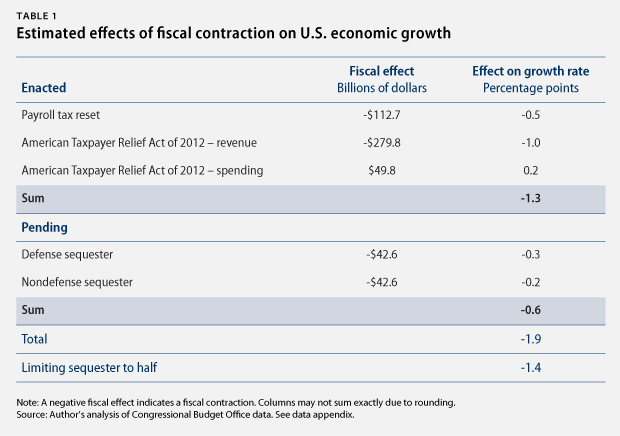

This brief explores the effects of recent fiscal policy actions on the prospects for U.S. economic growth and the ongoing recovery from the Great Recession. All told, the analysis in this issue brief finds that U.S. fiscal policy changes since the beginning of January 2013—and likely the policy choices made in the coming months as well—will shave 1.6 percentage points to 1.9 percentage points off of U.S. gross domestic product in 2013. (see Table 1)

The costs of the political conflict surrounding U.S. fiscal policy are twofold. First, by allowing U.S. economic policymaking to lurch from fiscal cliff to fiscal cliff, conflict over U.S. fiscal policy has cast a dark cloud of uncertainty over economic recovery not just in the United States but globally as well. Uncertainty surrounding the repeated debt-default brinkmanship deters productive investments in and hiring by the private sector, which has measurable effects on U.S. economic growth. The forecasting firm Macroeconomic Advisers estimates that the uncertainty costs America’s economic growth rate 0.5 percentage points.

Second, fiscal policy can prime economic growth when uncertainty about the economic future is high, therefore dampening private growth, and when monetary policy is already pushing hard on the economy through interest rates and quantitative easing. Through the right complement of public investments and basic social safety nets, however, fiscal policy can lay a foundation to sustain economic growth over the long term. Recent research from the San Francisco Federal Reserve, for example, shows that a dollar of public investment today can lead to two dollars of economic acceleration sustained over 10 years.

Unfortunately, current U.S. policymaking is moving fiscal policy in the wrong direction. As a result of the fiscal contraction—due to the tax and spending changes that have occurred since the beginning of the year—we can expect economic growth in 2013 to run 1.3 percentage points lower than would have otherwise been the case. The fiscal contraction includes:

- Resetting the temporary payroll tax cuts—which have been in place since the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009—back to 6.2 percent from the prior rate of 4.2 percent under the 2009 payroll tax cut. The fiscal contraction is expected to lower the U.S. economic growth rate by 0.5 percentage points in 2013, primarily by lowering disposable income, which will subsequently lower the consumption of working families.

- Revenue changes in the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012, which was signed into law on January 2, 2013. The act stopped a lot of the fiscal contraction that was scheduled to hit at the beginning of 2013, but it allowed some to continue. In particular, it ended extra tax cuts for earned income higher than $450,000 for households and $400,000 for individuals. While this method of raising revenue has a bigger bang for the buck than middle-income tax cuts or spending cuts—by trading off a relatively low economic impact for a high budgetary impact— the overall economy will still feel its effects. The American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 also reauthorized funds for extended temporary long-term unemployment benefits, offsetting some of the fiscal contraction. In total, however, we can expect economic growth to be 0.8 percentage points slower in 2013 as a result of the American Taxpayer Relief Act.

U.S. fiscal policy is still not out of the woods. On January 23, 2013, the Republican-led House of Representatives voted to suspend the federal debt ceiling for three months, setting the stage for another do-or-die fiscal battle in April or May. And in the meantime, President Barack Obama and congressional leaders will still need to contend with the “sequester”—automatic, across-the-board spending cuts to defense and nondefense spending mandated by the Budget Control Act of 2011, the law that ended our previous showdown over the debt ceiling in the summer of 2011.

The results of allowing sequestration to occur are predictable: The $85 billion in spending cuts slated to take effect from March 1 through the end of 2013 will cost the U.S. economy an estimated 0.6 percentage points of growth in 2013. The combined effect of these spending cuts and the recent changes to U.S. tax policy could dampen U.S. economic growth by 1.9 percentage points in the near term.

The good news: We don’t need to let this fiscal contraction disrupt the ongoing recovery or long-term U.S. economic growth. While deficits are high, the United States is by no means at risk of a sovereign debt crisis similar to those currently besetting a number of European economies—at least not because of any economic fundamentals. There is ample room for fiscal policy to reach a stable, sustainable path while completing the economic recovery and investing in a high productivity economy to drive future growth.

Why fiscal policy is especially powerful now

Broadly speaking, the government has two sets of macroeconomic policy tools that can influence the pace of economic activity and employment—fiscal policy that sets the level of tax revenues and public expenditures in the United States, and monetary policy that affects interest rates and therefore the costs of borrowing and investment.

Much of recent research confirms that the effects of fiscal policies on economic output and employment are magnified in times of economic weakness. This is particularly true when monetary policy is already doing almost as much as it can to bring down interest rates. The Federal Reserve has already reduced interest rates to near zero, effectively eliminating its most powerful tool to boost economic growth. When interest rates are so low, it’s cheaper for companies and people to borrow and spend.

When such economic conditions exist, as they do now in the United States, conventional monetary policy has already done much of what it can do. It is precisely at such times, however, that the multiplying effects of fiscal policy actions become greatly magnified—especially on the downside. Recent peer-reviewed economic research consistently finds that $1 of fiscal contraction can lead to as much as a $2.50 to $3 contraction in overall economic activity. This means that even small fiscal contractions can unleash substantial shocks on a U.S. economy that has not yet fully recovered to a stable path of economic growth.

Fiscal contraction from the American Taxpayer Relief Act and the Budget Control Act

On top of the economic uncertainty created by repeated brinkmanship on U.S. fiscal policy, fiscal policy changes that have taken place since January, as well as those set to take place in the first quarter of 2013, threaten to choke U.S. economic growth. Table 1 estimates the effects of fiscal contraction and the various tax and spending policy changes presently underway; the estimations are based on the “fiscal multipliers” that the Congressional Budget Office employed in its November 8, 2012, analysis of the effects of the so-called fiscal cliff and the newly updated estimates of different revenue and spending levels.

The American Taxpayer Relief Act eliminated tax cuts for top income and capital gains for households earning more than $450,000—and individuals earning more than $400,000—annually. At the same time, expiration of the payroll tax cut, which had been in effect since 2009, increased these taxes by 2 percent back to the normal 6.2 percent rate. The resetting of the payroll tax cut amounts to a $113 billion fiscal contraction—one that falls more heavily on low-income and middle-class working families than it does on the wealthy. The burden falls mainly on these workers because payroll taxes are capped, which means that the tax is not paid on an individual’s income higher than $113,700—or about the 90th percentile of income distribution. The combined effect of these fiscal contractions is expected to cut 1.5 percentage points from the U.S. economic growth rate in 2013.

The American Taxpayer Relief Act effected a fiscal contraction via taxes and revenue. It also reauthorized the extension of temporary unemployment benefits for the long-term unemployed—the now 39 percent of workers who have been out of a job for 27 weeks or more. This extension, along with other spending, helped to offset the fiscal contractions that the act caused, and, in doing so, is expected to put 0.2 percentage points back onto the U.S. growth rate.

All told, the contractionary effects of the American Taxpayer Relief Act and the other fiscal policy changes enacted at the beginning of January could weigh on economic growth by an estimated 1.3 percentage points through the end of 2013, as well as create a drag on the economy going forward. This is not the end of our fiscal predicament, however. On top of the recent changes in fiscal policy, a new series of broad-based spending cuts are set to take effect in the beginning of March—the sequester. If politicians do nothing and allow the sequester to take full effect, the $85 billion cuts slated through the end of this year are likely to reduce the economic growth rate by 0.6 percentage points in 2013.

Should our politicians proceed with this additional fiscal contraction, the outcome is again predictable: Policies already enacted are expected to shave some 1.9 percentage points off the U.S. economic growth rate in 2013. Even if policymakers claw back half of the sequester, we can still expect growth to slow by 1.4 percentage points in 2013 as a result of fiscal contraction.

The fundamental sustainability of a middle-out agenda

An oft-repeated claim by self-styled deficit hawks is that spending profligacy is bankrupting America and that the only way to put the U.S. economy back on track is to slash spending. In the recent fiscal negotiations, for example, House Speaker John Boehner (R-OH), pushed for “very specific proposals” in the party-line Republican-passed House budget that would have slashed Social Security and converted Medicare into a voucher system.

But claims of impending doom from U.S. government debt are simply not true. A Center for American Progress analysis of Congressional Budget Office data projects a 2013 federal budget deficit of approximately 6 percent of GDP in 2013. While certainly worthy of attention, the budget deficit is neither at unprecedented levels, nor is it near the level of roughly 10 percent of GDP that empirical research suggests can risk a sovereign credit crisis. The federal deficit has actually fallen from 10 percent of GDP at the peak of the Great Recession—an orthodox prescription of countercyclical macroeconomic policy—and now stands at near 6 percent, the same level at which it stood in 1983, when the U.S. economy exited its previous deepest contraction.

Another indicator suggesting that debt as a result of government spending is not a pressing, immediate economic concern comes from the Congressional Budget Office, which put the total U.S. debt held by the public at 73 percent of GDP in 2012. The present level is also well below the threshold that economists identify, on average, as potentially problematic—approximately 100 percent of GDP.

Under current law, doing nothing will shrink the U.S. debt to 58 percent of GDP by 2022. Although the U.S. debt and budget deficit remain elevated, sustainable fiscal policies consistent with revitalizing growth are within our reach—economically speaking, at least. The United States is nowhere near the economic conditions associated with a sovereign debt crisis. There is ample room for us to commit to fiscal policies that help grow the economy from the middle out.

Instead of choosing even more fiscal contraction, we need to make a different policy choice—one that recognizes the critical role fiscal policy and public investment play in strengthening and broadening America’s middle class and fostering American economic dynamism, the creative side of the market’s “creative destruction” that incentivizes people to take entrepreneurial risks and helps them recover from hard times. This is a “middle-out” approach to our economy. It recognizes the immense need for the United States to broaden the economic recovery while also expanding public investments in the foundations of growth and long-term productivity—education, infrastructure, science, prudent regulation, and essential social safety nets—and recognizes the financial potential of doing so. Over the medium-term, reforms that will lead to fairer and simpler tax systems overall are needed to ensure that the United States can efficiently raise the revenues needed to support spending on critical public goods and services.

Rather than running from buying U.S. Treasuries—as some conservatives predicted they would—professional investors and financial institutions around the world are clamoring to buy U.S. Treasury bonds. This allows the United States to invest in recovering economic growth today and in solving the social challenges that will lead to a competitive, broadly prospering economy. After accounting for inflation, the “real” value of an interest rate can actually run negative—meaning that rather than allowing them to earn interest, investors are willing to pay the United States a “safety premium” for the security of the Treasury bond assets that provide the backbone of the international financial system. This past December, in the midst of the fiscal showdown, the real interest rate on the Treasury Inflation Protected Securities 10-year Treasury bond fell to -0.87 percent. On the 30-year bonds, interest rates fell to just above zero, at 0.25 percent.

Despite the low interest rates, demand from the world’s investors is so strong right now that U.S. taxpayers earn back 75 cents for every $100 dollars borrowed to invest in recovering economic growth today and solving social challenges for a competitive, broadly prospering economy. In effect, private investors are choosing to vote with their trillions of dollars for what some conservative lawmakers are undermining through political gridlock, instead of advocating for deep fiscal contraction. There has never been a better time for the United States to borrow for the kinds of investment that can spark a revival in U.S. economic growth.

Conclusion

Again, the good news is that the United States still has ample policy space in which to finish the economic recovery from the Great Recession and to advance the investments needed for stronger growth over the long term. There is simply no economic rationale for politicians to allow more growth-sapping fiscal contractions.

At the very least, politicians should instead look to prevent any more fiscal contractions—especially those from the looming sequester that is set to take effect this March. Our political leaders can go even further, however, by eliminating the ineffectual debt ceiling altogether and rebalancing fiscal priorities toward investing in growth and recovery today and looking for more revenues over the longer term.

Adam Hersh is an Economist with the Economic Policy team at the Center for American Progress. Sam Ungar, the team’s Special Assistant, provided research assistance.