See also: “What Do We Know About Immigrants with Temporary Protected Status?”

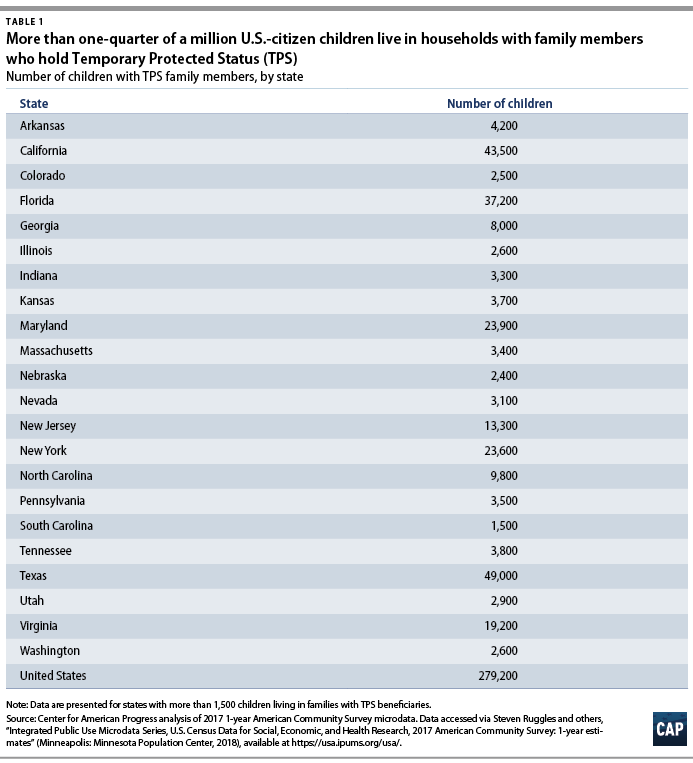

Over the past two years, the Trump administration has taken steps to strip protections from hundreds of thousands of immigrants in the United States with Temporary Protected Status (TPS), including for nationals from countries such as El Salvador, Honduras, and Haiti. The termination of TPS could have repercussions that affect both immigrants holding the status as well as their families, including 279,200 U.S.-citizen children under age 18 living with family members from these countries.1 Currently, multiple lawsuits are challenging the administration’s attempts to end TPS.2 However, should the terminations stand, after an average of 22 years living and working lawfully in the United States, Salvadorans, Hondurans, and Haitians with TPS would face an unimaginable decision.3

This fact sheet highlights the harmful effects that ending TPS could have on TPS holders’ children specifically and outlines three scenarios that could play out should the courts side with the Trump administration.

Scenario 1: Parents return, or are returned, to their country of origin while their children remain in the United States. Separating children from their families can cause emotional distress and economic insecurity and have significant, lasting consequences for children’s development.

- Children separated from their deported parents often show signs of trauma, such as depression, anxiety, frequent crying, difficulties in school, and disrupted eating and sleeping.4

- The effects of persistent stress can affect a child for their entire life, resulting in challenges with learning, behavior, emotion regulation, and physical health.5

Scenario 2: Parents return, or are returned, to their country of origin, taking their U.S.-citizen children with them and bringing them to countries facing severe, persistent challenges.

- The U.S. Department of State has issued travel warnings due to crime and civil unrest in El Salvador, Honduras, and Haiti. Meanwhile, numerous emails from U.S. Department of Homeland Security and cables from State Department consular staff underscore that conditions have not improved enough to send TPS holders back and that doing so would undermine regional stability and harm U.S. interests.6

- Taking these children to their parents’ home countries—areas that generally have higher rates of violence and fewer educational opportunities7—would be disruptive and expose them to serious danger.8

Scenario 3: Parents remain in the United States, losing their protection from deportation and work authorization. Living in constant fear of deportation weighs on all family members.

- Children as young as 3 years old are cognizant that their parent could be deported.9 Educators and other adults report widespread fear, anxiety, and behavioral changes among children in the immigrant community.10

- Even the potential threat of separation can cause children emotional distress. Studies show that children of immigrants experience feelings of vulnerability and fear of deportation and can experience psychological distress after simply hearing about families who are separated.11

- Increased stress related to deportation among parents and caregivers is associated with decreased emotional well-being and poorer academic outcomes among their children.12

As legal challenges to ending TPS work their way through the courts, parents and children are dealing with the stress of an uncertain future. Congress must protect these children’s parents, offering them a pathway to citizenship in the country that nearly all TPS holders have called home for decades.

Leila Schochet is the research and advocacy manager for Early Childhood Policy at the Center for American Progress. Nicole Prchal Svajlenka is a senior policy analyst of Immigration Policy at the Center.