Introduction and summary

The 2020 presidential election is less than a year away, and intelligence officials warn that foreign entities remain intent on affecting its outcome. At the same time, the U.S. House of Representatives is conducting an impeachment inquiry into President Donald Trump, due in large part to his solicitation of foreign interference from Ukraine in the 2020 presidential contest.

In the midst of these threats, Americans’ trust in government is near all-time lows, with voters deeply skeptical about a political system that they believe is corrupted and dominated by corporations and wealthy special interests.1 This dominance has been especially prominent since the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission unleashed a torrent of spending directed to super PACs and shadowy nonprofit organizations.2

Now more than ever, bold policy solutions are needed to help ensure that no foreign government, business, or person can unduly affect the nation’s democratic self-governance.

Before the Supreme Court’s 2010 decision in Citizens United, U.S. corporations had to finance campaign-related activity chiefly via disclosed donations from their employee-funded PACs. Corporations were not allowed to spend money directly from their corporate treasuries on independent expenditures—advertisements that expressly call for the election or defeat of a candidate. These ads are the lifeblood of election campaigns. But in Citizens United, the Supreme Court held that corporations are indeed permitted to spend corporate treasury funds on campaign-related ads, opening the door to unlimited corporate spending in U.S. elections.

Since the high court’s decision, corporations have taken full advantage of their new power. They have spent hundreds of millions of dollars, much of it through secret “dark money” channels, to elect their preferred candidates, often bankrolling negative advertising and distorting issues about which everyday Americans care.

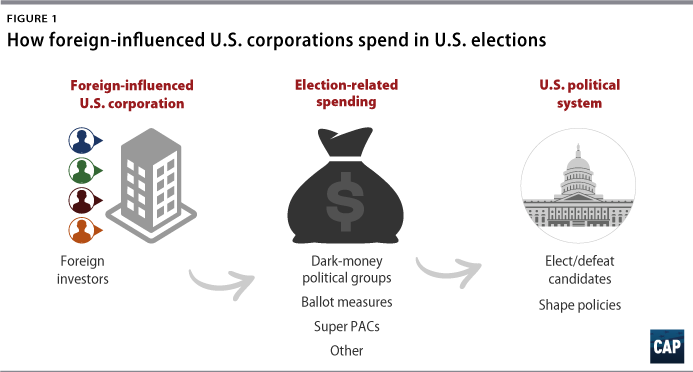

Yet attempts to influence U.S. elections can take other forms as well. Foreign influence in U.S. elections—specifically, foreign influence via U.S. corporations—merits particular attention, especially in the wake of unlimited corporate spending post-Citizens United.

Current election laws and Supreme Court precedent are clear when it comes to foreign influence: It is illegal for foreign governments, corporations, or individuals to directly or indirectly spend money to influence U.S. elections. These laws are foundational to U.S. democracy and exist primarily because foreign entities are likely to have policy and political interests that do not always align with America’s best interests.

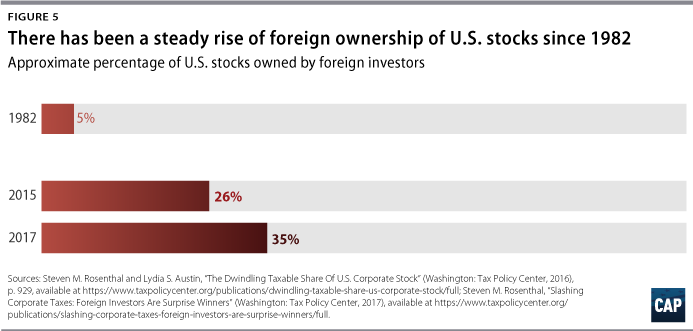

Unfortunately, the Citizens United decision opened an unexpected loophole that makes the United States more vulnerable to foreign influence. Because foreign entities can invest in U.S. corporations—and those corporations can in turn spend unlimited amounts of money on U.S. elections—foreign entities can now exert influence on the nation’s domestic political process. This is especially noteworthy as foreign investors now own a whopping 35 percent of all U.S. stock.3

Obama’s warning

An important warning about the potential effects of Citizens United came from President Barack Obama during a dramatic moment in his 2010 State of the Union address. Standing just feet away from justices of the Supreme Court, President Obama criticized the high court’s newly issued decision. He predicted that it would create a new avenue for special interests and foreign influence in U.S. elections:4

Last week, the Supreme Court reversed a century of law that I believe will open the floodgates for special interests—including foreign corporations—to spend without limit in our elections. I don’t think American elections should be bankrolled by America’s most powerful interests, or worse, by foreign entities. They should be decided by the American people. And I’d urge Democrats and Republicans to pass a bill that helps correct some of these problems.5

Justice Samuel Alito, a member of the high court’s conservative majority that had just decided the case, could be seen uttering the words “not true.”6 Unfortunately for U.S. democracy, however, Obama’s prediction about the harmful aftershocks of Citizens United has proved accurate.

In a political system that already allows corporations to cloak themselves in secrecy via unlimited dark-money spending, this foreign-influence loophole must be closed. The least lawmakers can do is block this avenue for inappropriate foreign influence in U.S. elections and in the policies that the federal government produces. Americans deserve to know that their best interests are paramount and that U.S. corporations are not acting as conduits for foreign influence in national affairs.

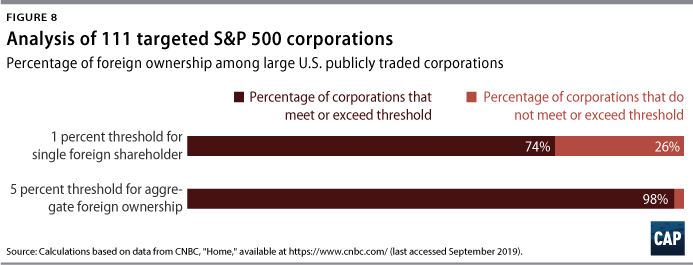

This report recommends a clear, strong policy solution: The United States must have bright-line foreign-ownership thresholds for American corporations that want to spend money in elections. These clear thresholds are supported by an array of lawmakers and regulators, as well as experts in constitutional and corporate governance law. This report applies the recommended foreign-ownership thresholds to many of the nation’s biggest publicly traded corporations, and the data show that applying these recommended thresholds likely would prohibit many of these corporations from spending funds to influence elections.

Stopping foreign-influenced U.S. corporations from spending money to affect U.S. elections is an issue of accountability that should transcend partisan political divisions. Unless and until lawmakers meaningfully address the problem of foreign influence in elections via U.S. corporations, they risk serious negative consequences for this country. In a properly functioning democratic society, a nation’s people must have faith in its elections, its elected leaders, and its government.

Background and scope of the challenge

Due to lax federal laws and reporting requirements, the United States is staring at two intersecting challenges that threaten the foundation of its democratic system. The first is secret corporate spending in U.S. elections, a problem discussed in detail in various Center for American Progress products, including “Secret and Foreign Spending in U.S. Elections: Why America Needs the DISCLOSE Act”7 and “Corporate Capture Threatens Democratic Government.”8

The second challenge, though not as problematic on its face, involves foreign entities who invest in American-based companies. These investments are problematic given lax disclosure laws, which make it easy to hide information about who is actually investing in these companies. Both of these challenges occur within the context of foreign governments and related entities attempting to steer the outcomes of U.S. elections.

During the 2016 presidential election, the United States became the target of systematic and sweeping foreign interference from Russia that was designed to alter the election’s outcome. As special counsel Robert Mueller, among others, has concluded, the Russian government orchestrated sophisticated efforts through state-funded media, third-party intermediaries, and paid social media users in a massive effort to influence America’s election outcome.9 And the dangers of these illegal activities continue. National security officials say that foreign entities are again seeking to interfere with the 2020 presidential election.10

Many of Russia’s ongoing actions violate longstanding laws that prohibit foreign involvement in U.S. elections and attempts to improperly influence the government and its leaders. At the same time, during 2019, President Donald Trump solicited foreign interference in the 2020 presidential election. The House’s impeachment inquiry into Trump is centered on his request that the president of Ukraine dig up dirt on one of Trump’s political rivals. Not only are Trump’s actions potentially illegal, they constitute an unconstitutional abuse of power.11 Regrettably, Americans are left with a situation in which Trump and his administration are thwarting necessary steps both to enforce laws against foreign influence in elections and to eliminate the threats that illegal interference poses to national security and the U.S. political community.

Yet inappropriate foreign influence in U.S. elections is not always overt. It often operates on the outer edges, or within loopholes, of U.S. law. This is true in the case of election spending by American corporations that have appreciable foreign ownership or control. Indeed, federal law does not effectively prevent a foreign entity from using a U.S.-based corporation to influence U.S. elections. In the age of massive foreign investment in American corporations, a new federal standard is necessary. Policymakers must ensure that U.S. corporations are not unduly influenced by their foreign investors when making spending decisions to attempt to affect American elections and policy.

Foreign interests diverge from domestic interests

Harvard Law School professor John C. Coates IV, a noted corporate governance expert, writes, “Democratic self-governance presumes a coherent and defined population to engage in that activity. Foreign nationals have a different set of interests than their U.S. counterparts, as regards a range of policies, such as defense, environmental regulation, and infrastructure. … Foreign and domestic interests predictably diverge.”12 Depending on the degree of their ownership or control, Coates writes, foreign investors “might be able to leverage ownership stakes in U.S. corporations to affect corporate governance. Through that channel, they could influence corporate political activity in a manner inconsistent with democratic self-government, or at least out of alignment with the interests of U.S. voters.”13

Elected officials must be accountable only to Americans, not to foreign investors who wield increasing amounts of corporate power. The best solution to the problem is a set of clear, effective rules, including foreign-ownership thresholds, that prevent foreign-influenced American corporations from spending money in U.S. elections.

The prohibition on foreign influence in U.S. elections

The roots of the ban on foreign influence in U.S. elections can be traced to the founding of the republic. The framers of the U.S. Constitution included a provision known as the emoluments clause, designed to prevent foreign payments to U.S. government officials and thereby reduce opportunities for foreign entities to corrupt the political system.14

George Washington used his farewell address at the end of his presidency to warn his fellow Americans that one of the greatest dangers to democracy involved the “insidious wiles” of foreign powers and the many ways that foreign powers could improperly influence the U.S. political system. Washington urged Americans “to be constantly awake, since history and experience prove that foreign influence is one of the most baneful foes of republican government.”15

Thomas Jefferson discussed the necessity of protecting the United States from “entanglement” in foreign politics, which he and other founders viewed with “perfect horror” due to the chance that U.S. officials could be corrupted by foreign entities.16 And Alexander Hamilton specifically highlighted the risk of a foreign power’s effort to cultivate a president or another top official, warning in “The Federalist Papers” of “the desire in foreign powers to gain an improper ascendant in our councils.”17

Building on these foundational concepts espoused by the nation’s earliest leaders, the federal courts have continued to uphold the government’s ability to exclude foreigners from participating in or influencing U.S. elections, including in one important recent case. In a 2011 decision, Bluman v. Federal Election Commission, which was summarily affirmed by the Supreme Court, the District Court for the District of Columbia wrote that excluding foreigners from U.S. elections is not only permissible but that doing so is “fundamental to the definition of our national political community.”18 This decision, decided fewer than two years after Citizens United by a special three-judge panel and written by future Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh, concluded that this foreign national exclusion “is part of a common international understanding of the meaning of sovereignty and shared concern about foreign influence over elections.”19 The court also stated that “the United States has a compelling interest for purposes of First Amendment analysis in limiting the participation of foreign citizens in activities of American democratic self-government, and in thereby preventing foreign influence over the U.S. political process.” It concluded that “the majority opinion in Citizens United is entirely consistent with a ban on foreign contributions and expenditures.”20

Importantly, the Bluman opinion makes clear the breadth of the ban on election spending by foreigners. In Bluman, the court affirmed the illegality of a Canadian citizen’s proposed election-related activity, even though it included only three $100 campaign contributions and payments for a flier supporting President Obama’s reelection. The chair of the Federal Election Commission (FEC), Ellen L. Weintraub, points out that “Bluman’s proposed activities were deemed illegal even though he hailed from a closely allied country, was lawfully working in the United States, and had proposed spending only an inconsequential amount of money. That’s how broad the foreign national political spending ban is.”21 (emphasis in original)

The decision in Bluman is based on federal law, where Congress has expressly prohibited foreign influence in U.S. elections. Under federal law, it is illegal for foreign nationals to spend money “directly or indirectly” or to provide anything of value in connection with U.S. elections.22 The term “foreign national” is defined to include not only foreign individuals but also foreign governments or other foreign entities, such as corporations.23 The prohibition includes election-related spending on independent expenditures and electioneering communications, and it extends to donations made to political campaigns, parties, and political action committees (PACs).24

Yet this federal law has loopholes ripe for exploitation and was written before Citizens United, when corporate spending was not a huge concern. First, the law says that a U.S. corporation that is owned or controlled by a foreign entity is not itself a “foreign national” so long as the corporation is organized under U.S. laws and has its principal place of business in the United States.25 In addition, there are no meaningful statutory standards to measure when a U.S. corporation may be violating the ban on “indirect” foreign influence in U.S. elections, such as by making election-related spending decisions that are influenced by the corporation’s foreign investors. To make matters worse, big loopholes in campaign finance disclosure laws and corporate transparency requirements make spending by foreigners nearly impossible to detect.26

The nation has reached a crucial juncture in its history. As FEC Chair Weintraub has compellingly written, U.S. elected officials must “be laser-focused on advancing the best interests of our country. And no other. This nation has shed blood, tears, and treasure over 2 ½ centuries safeguarding our democracy and the right of U.S. citizens to choose American leaders and policies.”27

Corporate spending in U.S. elections

Threats of foreign influence in U.S. elections are exacerbated by gaping holes in the law that allow dark money—spending by organizations that do not reveal their donors—to flood into federal, state, and local elections, often drowning out the voices of voters or even the candidates running for election.28 This disturbing lack of transparency allows billionaires, corporations, and outside organizations to secretly fund election-related activities, including advertising for or against candidates. Often, U.S. corporations—including foreign-influenced U.S. corporations—use dark-money spending as a vehicle to improperly and secretly influence the election of the nation’s lawmakers, which in turn affects the policies those lawmakers enact.29 [Note: This report uses the term “corporation” to refer to a full range of public and private, for-profit business entities, including limited liability companies (LLCs), partnerships, and sole proprietorships.]

How did America get to the point where corporate power over its elections threatens its democracy?

In a 1905 address to Congress, Republican President Theodore Roosevelt decried the corruption that resulted from unlimited corporate power and political spending.30 Roosevelt called for sweeping legislation to bar corporations from spending money to influence elections and to require full disclosure of campaign contributions and political expenditures. In response, Congress passed the Tillman Act in 1907 and the Federal Corrupt Practices Act in 1910.31 Over the next 100 years, Congress enacted a series of laws—most of them upheld in federal court—further regulating federal campaign financing, including by corporations.32

In the misguided Citizens United decision, the Supreme Court upended a century of precedent and allowed, for the first time, unlimited spending by corporations on independent campaign ads.33 The conservative majority of the high court wrote that the constitutional First Amendment rights of corporations cannot be abridged merely because they are corporations. They reasoned that because citizens enjoy the right to political free speech and corporations are “associations of citizens,” corporations also enjoy First Amendment privileges. This includes corporations’ unfettered right to spend unlimited amounts of money directly from their corporate treasuries to help elect the candidates that are most sympathetic to the policies they want.34 Republican Sen. John McCain (AZ), who was a longtime proponent of campaign finance reform, called the Citizens United decision the Supreme Court’s “worst decision ever.”35

A subsequent decision, SpeechNow v. Federal Election Commission, officially launched the super PAC era. SpeechNow allowed unlimited corporate contributions to super PACs and other political groups that spend money “independently” of candidates—in theory though not often in practice.36 Recent years have seen a proliferation of political groups that masquerade as social welfare nonprofits failing to disclose their contributors—including corporate contributors—while spending large sums of money advocating for and against candidates.

One way to help ameliorate this anti-democratic result would be to shine a bright light on corporate spending in elections. Even in Citizens United, the justices assumed that unlimited corporate political spending would be coupled with “effective disclosure,” which would “provide shareholders and citizens with the information needed to hold corporations and elected officials accountable for their positions and supporters.”37 Moreover, conservative Justice Antonin Scalia, who often viewed campaign finance laws with deep skepticism, supported the need for disclosure, writing in another case that “requiring people to stand up in public for their political acts fosters civic courage, without which democracy is doomed.”38

But mere months after the Supreme Court wrote about the importance of disclosing election-related spending, Senate Republicans killed legislation that would have required such disclosure.39 Without appropriate disclosure rules governing corporate spending in elections, it remains nearly impossible to know which candidates are being helped or hurt by the outsize voices of corporations, including foreign-influenced U.S. corporations. This dynamic runs the risk of rampant violations of the prohibition on foreign influence in U.S. elections.40

Political spending by corporations and by their employee PACs

Fortunately, in recent years, some corporations in the S&P 500 stock index have voluntarily disclosed their election-related spending, which is tracked by the annual CPA-Zicklin Index.41 For years 2015 through 2017, S&P 500 corporations that wished to disclose their direct federal and state election-related spending, not counting spending from their corporate PACs, expended a combined $773 million. This includes corporate spending that usually would remain “dark” if not voluntarily disclosed.42

Foreign-influenced corporations that engage in big dark-money spending from their corporate treasuries must by law report the copious amounts of money they spend to influence U.S. elections via another route: their corporate PACs. PAC money is comprised of contributions from a corporation’s U.S.-citizen managers and employees. The 111 S&P 500 corporations that CAP studied spent heavily via their PACs, doling out more than $83 million in the 2016 election cycle—years 2015 and 2016—to help elect their favored federal candidates.43 Although CAP’s recommended proposal would prevent foreign-influenced corporations from engaging in political spending from their corporate treasuries, it would not prohibit them from continuing to contribute funds from their corporate PACs, funds which come solely from U.S. managers and employees.

The amount of dark money being pumped into U.S. elections is staggering. Since 2006, groups that do not disclose their donors have spent at least $1 billion in dark money just to influence federal elections.44 In that same time period, an additional $1 billion has been spent by groups that only partially disclose their donors, bringing the total federal spending by groups that do not fully disclose their funders to at least $2 billion.45 That does not even include the more than $2.1 billion that outside groups have spent in state elections since 2005.46 It is important to bear in mind that all of these totals are just a subset of dark money—amounts that, while technically reported to the FEC or a state regulator, have no real donor information attached and therefore cannot be traced back to their source. It is impossible to know the actual amounts of dark money because some campaign spending takes advantage of dark-money loopholes and is not reported at all.

Isolating just the 2018 election cycle—which did not involve a presidential election, where vastly more money is spent to influence the result—outside groups that did not fully disclose their donors reported more than $539 million in spending. This set a new record for a nonpresidential election year.47 During that same election cycle, political committees that are required to disclose their direct donors reported receiving more than $176 million from shell corporations and other groups that do not further disclose their donors.48 Shell companies often can be organized as an LLC with little more than an opaque, nondescriptive name—that gives no clue as to its true owners—and a post office box address, which hides whether the owner is a foreign entity.49

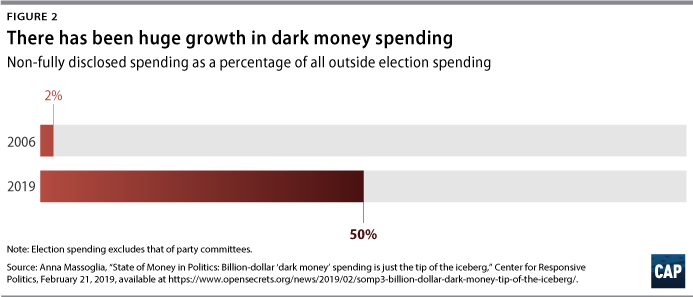

Not surprisingly, the percentage of outside spending in elections that has not been fully disclosed has skyrocketed after Citizens United. In 2006, before Citizens United, groups that did not fully disclose their donors comprised less than 2 percent of outside spending, excluding party committees.50 In sharp contrast, since Citizens United in 2010, this percentage has ballooned to more than 50 percent of outside spending, excluding party committees.51

Choosing the correct business form is the name of the game. After Citizens United, a growing number of political nonprofits decided to organize themselves under section 501(c) of the U.S. tax code. They gave themselves benign-sounding names and are now spending big sums of money to sway federal, state, and local elections.52 501(c) organizations can even accept donations directly from foreign entities, as long as those funds are not used for election-related spending. However, these same organizations can be engaged in election-related spending.53 And because 501(c) organizations are not required to disclose their donors, or fully disclose their election-related activities, it is virtually impossible to discern the extent of foreign-influenced corporate spending in U.S. elections.54

Two principal types of 501(c) organizations spend in politics:55 1) 501(c)(4) political nonprofits, or “social welfare organizations,” such as the National Rifle Association; and 2) 501(c)(6) nonprofit trade associations such as the Chamber of Commerce, the American Petroleum Institute, and the Business Roundtable.56 There are legitimate reasons for organizations to incorporate under these provisions. However, current laws provide avenues for other organizations to abuse these provisions in order to spend huge sums of money on election-related advertisements after pooling dark-money funds from contributors—often including U.S. corporations. In other words, some political organizations are successfully using legal fictions to shield true donors.57

U.S. Chamber of Commerce takes advantage of dark money

The most prolific dark-money group pumping money into elections is the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, a 501(c)(6) nonprofit trade association that advocates on behalf of its corporate members. The chamber, which directs almost all of its spending to help elect Republicans, spent a whopping $130 million on political advertisements between 2010 and 2018.58 The chamber does not generally disclose its donors and has urged companies to reject even voluntary disclosure of their political spending.59 But due to voluntary disclosure by some corporate donors, it is known that large foreign-influenced U.S. corporations are dues-paying members of the Chamber of Commerce and have given major sums of money to the chamber since 2010. For example, Dow Chemical Co. has contributed at least $13.5 million to the chamber; health insurance company Aetna Inc. has contributed $5.3 million; and oil company Chevron Corp. has contributed $4.5 million.60

Undisclosed dark money, including money raised by 501(c) groups, sometimes is funneled through other organizations, including super PACs, which then often use the money to flood close election races with negative advertising. Officially birthed with the 2010 SpeechNow case, super PACs are outside groups that may raise unlimited sums of money from people and entities such as 501(c)s or corporations—and then, under generic names like Americans for Patriotism, spend unlimited sums to overtly advocate for or against political candidates.61 Super PACs are only required to disclose their direct donors, such as 501(c) groups, but not the donors—including corporations—that send the millions of dollars of dark money to the 501(c) groups.

Outside spending in congressional races overwhelmingly is aimed at influencing the results of the most competitive elections across the country. Outside groups such as super PACs accounted for more than half of all television advertising in the most competitive Senate races in the 2018 cycle.62 In the same cycle, super PACs and dark-money groups collectively outspent the candidates’ own campaigns in a record-breaking 16 congressional elections.63

No wonder voters are so cynical about politics: 69 percent of television ads in the weeks leading up to the November 2018 midterm elections contained an attack on a candidate.64 And in the 2016 presidential primary, an analysis of advertisements aired by dark-money entities in 23 media markets found that 70 percent were attack ads, compared with only 20 percent of ads by other political groups.65

As the Center for American Progress has discussed, rampant dark money contributes to the toxicity of America’s political culture, which is being poisoned by the politics of personal destruction. People want to believe that their voices matter in the political system that is supposed to fairly represent them, and they are appropriately concerned that all of this undisclosed money fuels a massive, behind-the-scenes effort by corporations and special interests to obtain influence over the people’s government.66 In light of this toxic stew, Americans are demanding limits on political campaign spending. Two-thirds of Americans believe that new laws would be effective in reducing the outsize role of money in politics, with 77 percent wanting limits on the amount of money that can be spent on campaigns and 65 percent saying that new laws could be written to effectively reduce the role of money in politics.67 And a poll conducted immediately after the 2018 midterm elections revealed that 82 percent of voters believed that Congress’ first item of business should be anti-corruption legislation that should include cracking down on special interest money in politics.68

Justice Stevens’ warning

In his powerful dissent in Citizens United, Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens vividly explained the dangers of runaway corporate spending in U.S. elections:

Corporate “domination” of electioneering can generate the impression that corporations dominate our democracy. When citizens turn on their televisions and radios before an election and hear only corporate electioneering, they may lose faith in their capacity, as citizens, to influence public policy. A Government captured by corporate interests, they may come to believe, will be neither responsive to their needs nor willing to give their views a fair hearing. The predictable result is cynicism and disenchantment: an increased perception that large spenders “call the tune” and a reduced “willingness of voters to take part in democratic governance.” To the extent that corporations can exert undue influence in electoral races, the speech of the eventual winners of those races may also be chilled. Politicians who fear that a certain corporation can make or break their reelection chances may be cowed into silence about that corporation. On a variety of levels, unregulated corporate electioneering might diminish the ability of citizens to “hold officials accountable to the people,” and disserve the goal of a public debate that is “uninhibited, robust, and wide-open.” At the least, I stress again, a legislature is entitled to credit these concerns and to take tailored measures in response.69

Inappropriate spending in U.S. elections via foreign-influenced U.S. corporations

Clearly the United States faces a variety of challenges to its election system both from foreign influence and rampant, secret corporate spending. What happens when these challenges are exploited by inappropriate spending via foreign-influenced U.S. corporations, whether such influence is active or unintentional, warrants further scrutiny.

It is important to note, however, that there is no general obligation for U.S. corporations to disclose who their owners are, including foreign owners. According to estimates by Harvard Law School professor John Coates, there are more than 5 million corporations active enough to file tax returns with the Internal Revenue Service, and of those, less than 1 percent are publicly traded corporations. And even those publicly traded corporations are obligated only to disclose ownership of top officers, directors, and shareholders who own at least 5 percent of their shares.70 So in most circumstances, government regulators and the public are not able to discern whether a corporation is foreign-influenced or whether a foreign-influenced corporation has spent from its treasury to sway U.S. elections.

Federal law says that if a domestic subsidiary of a foreign parent is incorporated within the United States and has its principal place of business within the United States, it is not a foreign national.71 But the law does not specifically address the situation of a foreign entity owning or influencing a U.S. corporation. Although the law broadly prohibits foreigners from spending in U.S. elections—“directly or indirectly”—Congress has left it to the Federal Election Commission, the federal agency with jurisdiction over election spending, to determine when a U.S. corporation is acting on behalf of a foreign entity.

In turn, the FEC has continued to work under minimal and insufficient regulatory requirements, developed before Citizens United radically reshaped the campaign finance system. Previously, the FEC only had to concern itself with limited contributions from corporate PACs—money raised under strict circumstances from individual corporate employees. The FEC determined, reasonably, that a foreign parent and U.S. subsidiary relationship at least calls the U.S. subsidiary’s election-related spending into question. And via a regulation and a series of advisory opinions, the FEC has developed a framework to look at spending by corporations with foreign ownership. Under the FEC’s framework, an American corporation that is owned in part or in whole by foreign investors is permitted to spend money in U.S. elections if the corporation clears two exceedingly low hurdles: 1) no foreign national can be involved in the decision-making about such spending; and 2) the expended funds are generated solely in the United States.72

This framework developed for the pre-Citizens United era is extremely lax, and Republican FEC commissioners have resisted promulgating any meaningful regulatory updates. Foreigners can actively attempt—and have attempted—to evade this framework’s restrictions. But just as importantly, there is rampant election spending by foreign-influenced U.S. corporations that complies with the letter of the law but unintentionally pushes the outer boundaries of the regulatory framework to its breaking point. This allows foreign-influenced corporate spending to seep into U.S. elections. Former ethics counselor to President Obama, Norman Eisen, has observed, “It’s a sad state of affairs, but the worst scandal in the United States is what’s legal.”73

Active illegal spending via American corporations

Some foreigners continue to exploit the United States’ lax campaign finance system with the goal of illegally influencing election outcomes. Often, these attempts involve secretive back-channel money and/or opaque business entities, which leave U.S. elections open to increasingly aggressive actors such as Russia and China, nations known to exercise control over their domestic companies without owning a direct stake in them.

FEC Chair Ellen L. Weintraub has stated that “the doors are wide open for political money to be weaponized by well-funded hostile powers.”74 Weintraub recently testified that the number of matters before the FEC that include alleged violations of the foreign-national contribution ban increased from 14 to 30 in the period from September 2016 to September 2019.75 Weintraub also lamented that FEC enforcement actions in these types of matters are hampered by low staffing levels, multiple commissioner vacancies, and disagreements with Republican-appointed commissioners who are reluctant to bring enforcement actions.76

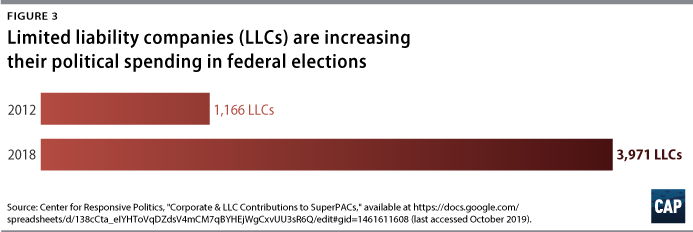

Active illegal spending in U.S. elections frequently is facilitated by shell organizations, including limited liability companies, which often do not disclose their beneficial owners, even to state regulators. Beneficial owners are entities who may not be on record as an owner—often called a “nominal” owner—but who may indirectly exercise control over a corporation through ownership interests, voting rights, agreements, or otherwise or have an interest in or receive substantial economic benefits from the corporation’s assets.77 Beneficial owners can run shell companies through one or more countries and/or multiple layers. As Sheila Krumholz, executive director of the Center for Responsive Politics, has testified, “since the unique structure of LLCs often requires the entities to disclose only minimal information necessary for incorporation, LLCs have become attractive vehicles to move funds through different opaque entities like ‘shell’ companies in elaborate, complicated financial transactions funneling money into U.S. elections without ever disclosing its source,” which can become conduits for quietly influencing U.S. elections.78

Between 2012 and 2018, LLCs spent approximately $107 million to influence federal elections.79 And the number of LLCs that routed this money into federal elections nearly quadrupled from 2012 to 2018, swelling to almost 4,000 LLCs.80

As Krumholz testified to the U.S. Senate, “The scale and sophistication of these operations presents grave challenges to the integrity of the American political system.”81 When money is laundered through shell corporations set up to protect anonymous donors, this lack of disclosure certainly denies Americans the ability to see “whether elected officials are ‘in the pocket’ of so-called moneyed interests,” as Justice Anthony Kennedy emphasized in the Citizens United decision.82 These problems are not likely to subside anytime soon, as the United States is now the second-most-popular destination in the world to incorporate shell companies, after Switzerland and before the Cayman Islands.83

There are many recent examples of foreigners allegedly actively trying to spend money in U.S. elections through various means. (see sidebar) Aided by outdated laws, a weak regulatory framework, and lax federal enforcement, this active spending by foreigners in U.S. elections poses a threat to America’s sovereignty, national security, and body politic. It is imperative that the United States make it far easier to detect and stop illegal influence in its elections.

High-profile examples of lawbreaking

Existing federal laws have been broken—or allegedly broken—using LLCs, other corporate forms, and/or straw men, in attempts to actively influence U.S. elections.

In 2017, the federal government successfully prosecuted a wealthy Mexican businessman, his son, and his U.S.-based political consultant for a 2012 scheme in which the Mexican businessman donated approximately $600,000 in foreign-originated funds through multiple U.S. shell corporations to help elect candidates in San Diego, California, including former Mayor Bob Filner (D). The aim of the Mexican businessman was to elect politicians who would support his development plans and real estate ventures.84 There is no evidence that the candidates knew of this illegal activity.

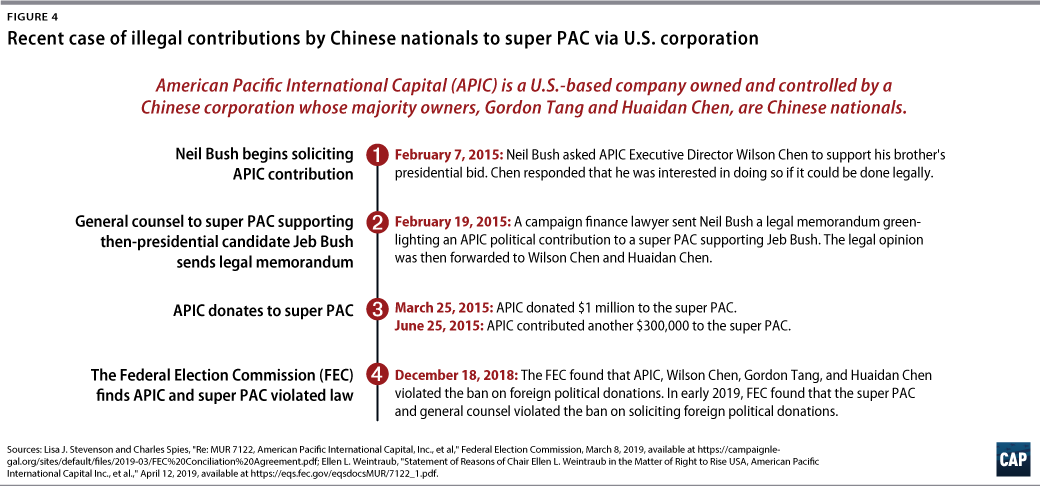

In 2019, the FEC levied record fines against two Chinese nationals who attempted to buy political influence by steering $1.3 million to a major super PAC supporting the presidential campaign of Jeb Bush through a U.S. corporation that the Chinese nationals owned and controlled. The FEC also fined the super PAC for its role because Bush’s brother, Neil Bush, solicited the contribution on behalf of the super PAC.85 This was an exceptionally rare case where indisputable direct evidence—in the form of written communications and, basically, a confession to a reporter—exposed the illegal foreign influence, which forced even the recalcitrant Republican FEC commissioners to hold the foreign-influenced U.S. company and the super PAC accountable.

In 2019, the federal government indicted Malaysian financier Jho Low and Fugees rapper Prakazrel “Pras” Michel for using shell companies and straw men to make more than $1 million in illegal foreign contributions to President Barack Obama’s 2012 reelection campaign and a pro-Obama super PAC in an unsuccessful attempt to buy political influence. Low also has been tied to alleged suspicious money transfers to President Trump’s joint fundraising committee.86 Notably, in 2016, the FEC’s Republican commissioners blocked an effort from their Democratic counterparts to open an investigation.87 Low and Michel have denied the charges, and there is no suggestion that the campaigns or political committees involved were aware of this illegal activity.88

In 2019, the nonpartisan, nonprofit Campaign Legal Center filed a complaint with the FEC against Barry Zekelman, a Canadian citizen, and his U.S.-based company Wheatland Tube LLC, which one year earlier had made at least $1.75 million in contributions to a super PAC supporting Donald Trump. Zekelman, who later successfully lobbied President Trump and the administration on policies favorable to his steel business, allegedly told Wheatland Tube executives that he wanted to find a way to contribute to the super PAC in order to support Trump. Although Zekelman denies any wrongdoing, and there is no evidence that the super PAC was aware of this allegedly illegal activity, Zekelman may have violated the law that bans foreign investor participation in a corporation’s decision-making about election-related contributions.89

On October 10, 2019, the federal government charged two U.S. citizens with Ukraine connections with a wide range of campaign finance-related crimes, facilitated in part by an alleged shell corporation they set up. The alleged crimes by these defendants—Lev Parnas and Igor Fruman—include attempting to circumvent federal laws against foreign influence in U.S. elections. Both defendants were also allegedly involved in efforts by the administration and President Trump’s personal attorney Rudy Giuliani to pressure the Ukrainian government to interfere in the 2020 presidential election. According to the indictment, the two defendants funneled foreign money to federal and state candidates so that the defendants could buy potential influence for themselves and for at least one Ukrainian government official. Part of their scheme allegedly involved setting up a U.S. shell company as an LLC that two days after incorporation in May 2018 made a $325,000 straw donation to the main super PAC supporting Donald Trump.90 Parnas and Fruman also allegedly conspired to make political contributions that were secretly funded by a Russian businessman with the goal of winning support for a marijuana business. Notably, the defendants had several in-person meetings with President Trump and have donated or directed hundreds of thousands of dollars to Republican candidates in recent years, including by hosting fundraising events.91 The two defendants pleaded not guilty, and Giuliani has denied any wrongdoing. The nonpartisan, nonprofit entity that helped uncover this alleged scheme, the Campaign Legal Center, says there is evidence the super PAC that accepted the $325,000 straw donation knowingly misattributed the source of the funds, which the super PAC denies.92

The loophole for foreign-influenced U.S. corporations

The federal government’s interest in regulating foreign influence need not rest on the idea that foreign investors may be linked to hostile entities that are actively trying to weaken U.S. democracy or intentionally flouting U.S. laws against foreign interference in elections. Rather, because current federal law does not explicitly prevent a U.S.-based corporation with foreign owners from spending money in elections, foreign interests are almost inevitably going to influence the political system—because corporate managers are going to make their political decisions with the interests of their foreign investors in mind. At the very least, this dynamic creates a harmful appearance of impropriety that can weaken Americans’ trust in elections; in government officials; and ultimately, in the policies that those officials produce.

As FEC Chair Weintraub has observed, although the ban on foreign national spending in U.S. elections is crystal clear and well-established, the scope of the ban can be murky.93 Even fully disclosed money spent by U.S. corporations with an appreciable share of foreign ownership raises concerns about foreign influence, even where there is no intent to illegally influence U.S. elections.94 That’s because a foreign-influenced U.S. corporation has interests that are likely to diverge from American interests.

Analysis of election spending by foreign-influenced U.S. corporations must be informed by the fact that foreigners are increasingly buying ownership stakes in American corporations. In 1982, foreigners owned just 5 percent of U.S. corporate stock. That percentage grew precipitously to 26 percent by 2015.95 The latest estimate is that foreign ownership of U.S. stock now stands at approximately 35 percent.96 Incidentally, this means that approximately 35 percent of the benefits of recent corporate tax cut legislation—$40 billion per year, according to one estimate—is going to foreigners.97 Some observers expect foreign ownership of U.S. stock to grow even further, especially via sovereign wealth funds.98

When a significant fraction of a U.S. corporation’s shareholders are not Americans, corporate managers are attuned to “a different set of incentives,” and the fiduciary duties that managers owe to their foreign shareholders influence decisions about spending in U.S. elections.99

Divergent interests

In the election spending context, the principal challenge presented by foreign ownership of U.S. corporations is that when these corporations spend in U.S. elections, “they may not have U.S. interests at heart.”100 In the policy areas of tax, defense, and commerce—just to name a few—there are many ways that foreign interests predictably diverge from American interests. For example, foreign investors generally would not support a U.S. policy that would erect barriers to foreign investment in American real estate or equity markets or require foreign investors to disclose more information about themselves and their holdings in order to invest in these markets. Interests could also diverge around a U.S. policy that mandated that certain products be made in the United States or that trading partners must meet minimum standards regarding labor and environmental practices.

Over the past dozen years, U.S. subsidiaries of foreign corporations have waged campaigns against numerous legislative proposals that would have hurt their business interests but could have benefited Americans. For example, American subsidiaries of foreign corporations opposed legislation that would have required greater disclosure of lobbying activities by foreign agents.101 Similarly, foreign-owned U.S.-based subsidiaries lobbied against legislation that would have expanded the scope of the U.S. government’s national security reviews of foreign investment, which could have slowed plans by foreign companies to expand their operations in the United States.102 Moreover, foreign-owned corporations doing business in the United States have taken advantage of various states’ lax labor-related and environmental laws—in particular, so-called right-to-work laws in the South—to undercut U.S. manufacturers and their union workforces. To the extent that U.S. manufacturers face such low-road competition, it makes it harder to maintain stronger American labor standards and may also spur offshoring, outsourcing, and other related practices that do not benefit U.S. workers.103

In some instances, the U.S. corporation’s managers explicitly know the policy preferences of their foreign investors. At the very least, the U.S. corporation’s managers implicitly know the policy preferences of their foreign investors. Whether explicit or implicit, foreign shareholders’ policy interests can appreciably influence the managers’ decision-making in ways that are not aligned with the interests of Americans. When a U.S. corporation’s managers feel obliged to spend corporate resources in ways that serve the interests of foreign shareholders—instead of only the American people—this allows foreign influence to impermissibly seep into U.S. elections and ultimately the nation’s policymaking.

CEO admits importance of foreign interests

In a stark illustration of how foreign-influenced U.S. corporations make decisions, the then-CEO of Exxon Mobil, Lee Raymond, once declared, “I’m not a U.S. company and I don’t make decisions based on what’s good for the U.S.”104

As scholar Norman J. Ornstein observed, in today’s world of multinational corporations, it is much rarer for a U.S. corporate CEO to be able to make the statement made in 1953 by General Motors CEO Charles Wilson: “What’s good for General Motors is good for America and vice versa.”105

Fiduciary duties

Not only do foreign investors have interests that will diverge from the interests of Americans, but corporate managers have fiduciary obligations to consider those interests.106

The concept of fiduciary duty is one of the most fundamental concepts in corporate governance law. Fiduciary duties include the duties of loyalty and care owed by corporate managers—officers and directors—to their shareholders.107 As explained by noted corporate governance expert John Coates: “The board of a public company generally conceives of themselves as working for the shareholders.”108 In carrying out their duties, corporate managers generally are thought to have one main required focus: maximizing profits for shareholders.109 In other words, “the long understood reality [is] that the stockholders of business corporations do not invest for any common interest other than receiving a good return.”110 This is also known as the “shareholder primacy” theory, which posits that a corporation’s sole purpose is to maximize shareholders’ wealth and that corporate managers or boards must prioritize increasing the corporation’s share price above other considerations, including workers, consumers, future generations, or the environment.111 Although experts, policymakers, and activists have raised many concerns with this approach, it is the dominant mode of thought in most corporations.

The fiduciary duty owed to foreign shareholders necessarily “affects the policy decisions the company supports, the candidates they may support, lobbying on certain laws that may affect their business model, ideas about what countries it wants to engage in trade with—all of those are affected by having a significant foreign owner.”112 Managers of foreign-influenced U.S. corporations are aware of how their foreign parent companies or foreign investors would want the corporation’s money to be spent to influence elections. In essence, it is their job to know.

Larry Noble, former general counsel of the FEC, has observed, “It is naive to believe that the U.S. managers of a domestic corporation with substantial foreign ownership are not going to [be] cognizant of that ownership when they make political expenditures or that domestic corporations cannot be used to funnel foreign money into U.S. elections.”113 Another expert, Brendan Fischer of the Campaign Legal Center, similarly has observed that even where foreign investors do not explicitly share their views with corporate managers, the managers nonetheless likely will know enough about what those investors want—and take those views into account.114

Why is this important? Under the current regulatory framework, U.S. corporations with foreign ownership—even including wholly owned subsidiaries of foreign entities—are given broad latitude to spend in U.S. elections. The chief restriction is that the U.S. corporation must prohibit any foreigner from participating in the corporation’s decision-making process about such spending. But the theory of fiduciary duty, combined with shareholder primacy, renders this requirement almost meaningless. Even when foreign investors play no explicit role in the decision-making process of a U.S. corporation’s managers, the interests of foreign investors implicitly affect the managers’ decision-making process. Complicating this even further is that “[m]ultinational corporations often employ diverse leadership—consisting of Americans and foreign nationals from a variety of countries—making it difficult in most cases to discern whether ‘foreign influence’ is being exerted in the decision to invest in U.S. elections.”115

Boiled down to its essence, “When a U.S.-based company is owned by foreigners, the U.S. managers, even if they are U.S. citizens, would be breaching their fiduciary duties if they spent company resources other than in the best interest of their foreign owners.”116 This lends further evidence to the need for a strong federal law to set bright-line standards to limit spending in U.S. elections by foreign-influenced U.S. corporations.

Examples

How does all this play out in real-life examples, where corporations are able to lawfully take advantage of existing loopholes? It runs the entire gamut, from U.S. corporations that are 100 percent owned by foreign entities to U.S. corporations that have much smaller—yet still meaningful—levels of foreign ownership.

The starkest examples involve U.S. corporations that are wholly owned subsidiaries of foreign entities, such as Panasonic Corp. of North America, Michelin North America, Inc., Shell Oil Co., and Anheuser-Busch.117 For instance, the U.S. tobacco company Reynolds American Inc. was wholly acquired by London-based British American Tobacco in July 2017. After it became foreign-owned, Reynolds increased its political spending in U.S. elections, funneling $1.2 million to super PACs during the 2018 cycle, more than any other U.S. wholly-foreign-owned corporation. Notably, all of this was directed to entities dedicated to electing conservative lawmakers.118

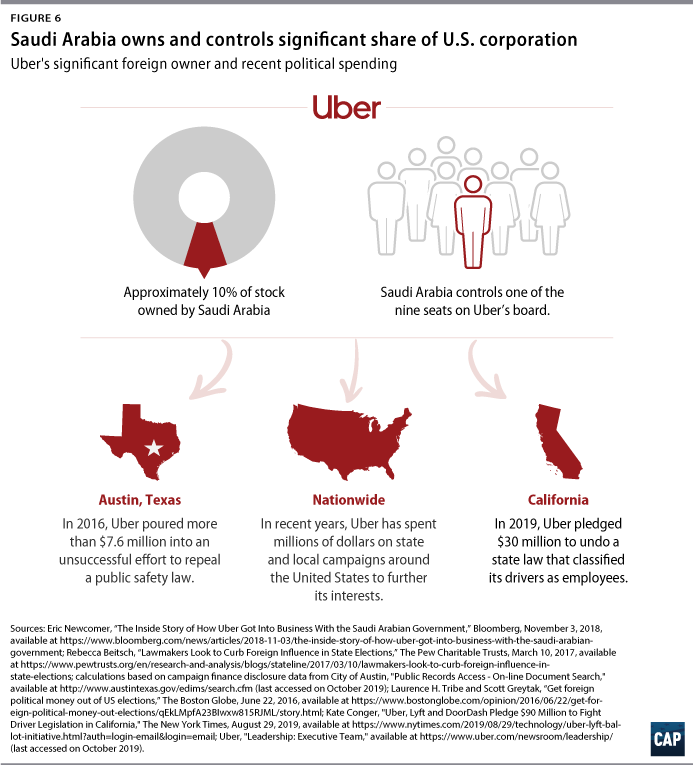

Consider Uber, a U.S. corporation in which the kingdom of Saudi Arabia spent $3.5 billion to buy approximately 10 percent of its corporate stock and a seat on the board of directors.119 In 2016, Uber spent a whopping $7.6 million on a local measure in Austin, Texas, fighting against a law that required drivers to submit to fingerprint-based criminal background checks.120 When combined with spending by ride-sharing company Lyft, this spending was nine times the previous record for election spending in Austin.121 This is in addition to the tens of millions of dollars that Uber has spent in other local elections or on ballot measures across the nation from Seattle to Washington, D.C., including a pledge to spend $30 million on a 2020 California ballot initiative regarding the employment status of ride-share drivers.122

Or consider spending on state and local ballot initiatives by U.S. corporations with appreciable levels of foreign investment:

- Amazon spent $1.5 million to influence the results of Seattle’s November 2019 city council races, donating through the local chamber of commerce’s PAC.123 This huge political expenditure caused one council member to announce her support for a city ordinance to ban political spending in Seattle elections by foreign-influenced corporations such as Amazon, and she predicted that the city council will pass it in the future.124

- In 2018, dialysis company DaVita spent more than $66 million to successfully defeat a California ballot initiative that would have capped the amount of money that dialysis providers could earn on certain patients.125

- In 2016, Pinnacle West Capital Corp. spent approximately $38 million to successfully defeat an Arizona clean energy ballot measure that would have required electric cars to rely more heavily on renewable resources for their electric supply.126

- In 2016, Duke Energy expended almost $6 million in a successful effort to stop a Florida initiative that would have expanded residential access to rooftop solar power; the campaign waged by Duke Energy and allied companies was criticized as “deceptive” by at least one Florida newspaper.127

Another state-based example involved Chevron, a corporation with significant foreign ownership, which spent $3 million in 2014 to influence the mayoral and city council races in Richmond, California. Much of Chevron’s money went into PACs that aired television ads aimed at defeating candidates who were critical of a local refinery owned by Chevron, which was sued twice by Richmond after refinery explosions sickened local residents.128 According to one expert, between 1988 and 2014, Chevron spent a staggering sum of more than $68 million to influence state elections, where political spending can have greater impacts than in higher-dollar federal elections.129

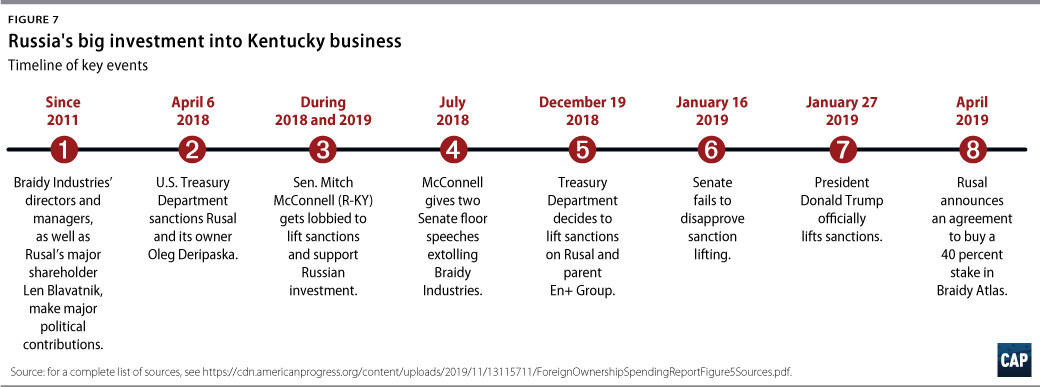

Or consider a recent, high-profile example involving Russian ownership of a politically powerful U.S. corporation based in Kentucky. In April 2019, a giant Russian aluminum company, United Co. RUSAL PLC, announced an agreement to acquire a 40 percent ownership stake in a Kentucky-based aluminum processing company.130 The Russian company is controlled by En+ Group PLC, a company with headquarters in Moscow and a “registered office” on the British island of Jersey.131 The U.S. company—Braidy Atlas, which is owned by Braidy Industries Inc.—will build and operate a cutting-edge aluminum rolling mill made possible because of Rusal’s $200 million investment in the U.S. company.132 The business arrangement also will make Braidy Industries the largest customer of Rusal.133

Just one year earlier, the United States had sanctioned Rusal and En+ Group, along with their Russian owner, oligarch Oleg Deripaska, barring them from doing business in the United States.134 The sanctions were imposed in part because of Deripaska’s deep Kremlin connections and more generally because of Russian attempts to “subvert Western democracies,” which included interfering with the 2016 U.S. presidential election.135 However, in December 2018, President Trump’s Treasury Department decided to lift the sanctions on three of Deripaska’s companies, after the oligarch decreased his ownership stakes.136 Registering its sharp objections to lifting the sanctions, the U.S. House voted in a bipartisan fashion to stop the Trump administration’s move, but Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) blocked the disapproval in the U.S. Senate.137

Leader McConnell, who represents Kentucky, was well-versed in matters related to Braidy Industries and Rusal. During 2018 and 2019, Leader McConnell was lobbied heavily by representatives of En+ Group and Braidy Industries, including former Sen. David Vitter (R-LA) and several former top advisers in McConnell’s Senate office about lifting the sanctions and the business deal.138 Moreover, Braidy Industries’ CEO, Craig Bouchard, reportedly spent months building a personal relationship with McConnell and pressing him on relevant policy issues.139 In July 2018, McConnell even delivered two speeches on the Senate floor that highlighted Braidy Industries’ work, one of which Braidy Industries touts on its public website.140

Critics from across the political spectrum said the deal allows Russian interests to seep into the U.S. political system in a way that could undermine U.S. interests.141 This is especially true where Russia may be seeking to grow its share of the world’s aluminum market and may be opposed to American tax, environmental, or trade policies that could thwart its expansion. Given the close relationship that Braidy Industries has with Leader McConnell, under current law, Braidy Atlas—which is 40 percent owned by Rusal—could decide to donate money from its corporate treasury to entities helping reelect McConnell or his allies. As discussed above, it would be next to impossible to trace any political spending in which Braidy Atlas may engage back to foreign pockets or foreign influence.

Analysis of public filings reveals that Braidy Industries’ CEO, Craig Bouchard, has donated to conservative campaign committees, including the Senate Conservatives Fund and the House Freedom Fund.142 Public filings also reveal that since 2011, several directors and managers of Braidy Industries have donated approximately $250,000, largely to conservative candidates or campaign committees.143 Moreover, during the 2018 election cycle, one of Rusal’s longtime major owners, Len Blavatnik—a Ukrainian-born U.S. citizen with deep ties to the Kremlin—contributed more than $1 million through his companies to a major McConnell-aligned super PAC that helped Republicans retain control of the Senate.144 It is logical to assume the possibility that Braidy Atlas—as well as Braidy Industries, which is now closely tied to Rusal—may want to spend corporate treasury funds on upcoming U.S. elections, given the track records of election spending detailed above. An updated federal law should prevent this type of inappropriate foreign-linked election spending from happening.

Republican FEC commissioners block strict foreign-ownership standards

The Federal Election Commission is responsible for overseeing many facets of U.S. elections, including ensuring that foreigners do not directly or indirectly spend money to influence elections. The current chair of the FEC, Ellen L. Weintraub, believes that a new framework is needed to ensure that U.S. political spending is free from foreign influence. Backed by constitutional scholars such as Harvard Law School professor Laurence H. Tribe,145 Weintraub set out her argument in a 2016 op-ed in The New York Times.146 Weintraub’s analysis goes like this: In the misguided decision in Citizens United, the narrow majority of the Supreme Court decided that corporations are “associations of citizens” that enjoy the same political free speech rights enjoyed by citizens. “In other words, when it comes to political speech, which the court equated with political contributions and expenditures, the rights that citizens hold are not lost when they gather in their corporate form.” Weintraub then restated the bedrock principle that foreigners are “forbidden by law from directly or indirectly making political contributions or financing certain election-related advertising known as independent expenditures and electioneering communications.” Thus, under the majority’s flawed but precedential decision in Citizens United, “when the court spoke of ‘associations of citizens’ that have the right to participate in American elections, it can only have meant associations of American citizens who are allowed to contribute.”

Continuing her analysis, Weintraub wrote:

Since the [Supreme] [C]ourt held that a corporation’s right to participate in elections flows from the collected rights of its individual shareholders to participate, it follows that limits on those individuals’ rights must also flow to the corporation. You cannot have a right collectively that you do not have individually. Individual foreigners are barred from spending to sway elections; it defies logic to allow groups of foreigners, or foreigners in combination with American citizens, to fund political spending through corporations. If that were true, foreigners could easily evade the restriction by simply setting up shell corporations through which to funnel their contributions. Arguably, then, for a corporation to make political contributions or expenditures legally, it may not have any shareholders who are foreigners.147

Dating back to 2011, a year after Citizens United, Weintraub, joined by Democratic and independent FEC commissioners, has urged the FEC to promulgate new regulatory standards to prevent inappropriate foreign influence in U.S. elections via U.S. corporations.148 Nonetheless, even in the face of widespread support from comments filed by the public, the FEC’s Republican-appointed commissioners have blocked all attempts to meaningfully update the agency’s inadequate rules.149

In her ongoing effort to push for bold policy solutions, in June 2016, then-Vice Chair Weintraub convened a public forum at the FEC to explore, in her words, “the risks of foreign influence in a period of lightly regulated corporate political spending” and to discuss potential policy solutions.150

The forum, attended by the FEC commissioners, included presentations from a wide array of leading public policy professionals, academics, and attorneys, including experts in corporate governance and election law. The forum’s panelists generally agreed on the need for new regulatory standards—using foreign-ownership thresholds—to limit foreign-influenced corporations from spending money to influence U.S. elections without detection.151 Much of the conversation focused on the appropriate levels to set those thresholds, with general consensus around the need for the thresholds to be set at levels that were low yet supported by corporate governance theories and practicalities.

Just a few months later, in September 2016, the FEC took up the issue again at a public meeting.

Weintraub twice proposed new regulations that would include setting ownership thresholds governing how corporations with foreign links could spend political money, as well as heightening disclosure to prevent foreign interests from spending through dark-money sources that could not be traced.152 Commissioner Ann Ravel also proposed rescinding the FEC’s existing advisory opinion allowing domestic subsidiaries of foreign corporations to spend on politics.153 In contrast, the Republican commissioners suggested imposing a requirement that corporations certify compliance with existing standards, which the Democratic commissioners correctly argued is insufficient on its own to deal with the threats of foreign influence in U.S. elections.154 The commissioners deadlocked on all of the proposals.155

Since that time, Weintraub has been relentless, asking her fellow commissioners in January 2017,156 June 2017,157 and May 2018158 to begin a rulemaking proceeding. But Republican commissioners rejected all of these efforts as “not necessary” or “premature.”159 Indeed, those same commissioners even blocked a proposed new rule for corporations that are wholly owned by foreign governments.160

Time and again, obstruction by Republican FEC commissioners has kept the agency from setting a strong, clear framework. This obstruction is coupled with weak enforcement. Moreover, the FEC has a small and overworked staff. Sadly, it often takes a “smoking gun” to provoke meaningful action, as in the FEC’s enforcement action involving the Jeb Bush super PAC, discussed above. Quite clearly, Congress must step in to enact new and meaningful statutory requirements that would prevent foreign-influenced U.S. corporations from spending in U.S. elections.

Recommendations

A bold new framework is needed to stop inappropriate foreign influence in the U.S. political system. Congress should enact bright-line ownership thresholds to prevent election spending by foreign-influenced U.S. corporations. A clear, strong law would prohibit U.S. corporations—those that exceed meaningful yet low thresholds of foreign ownership or control—from spending money directly from their corporate treasuries in any federal or state elections. Foreign-ownership thresholds are supported by constitutional and corporate governance experts, as well as federal lawmakers and regulators.

The Center for American Progress recommends a policy solution that deems a U.S. corporation to be foreign-influenced under three key scenarios:

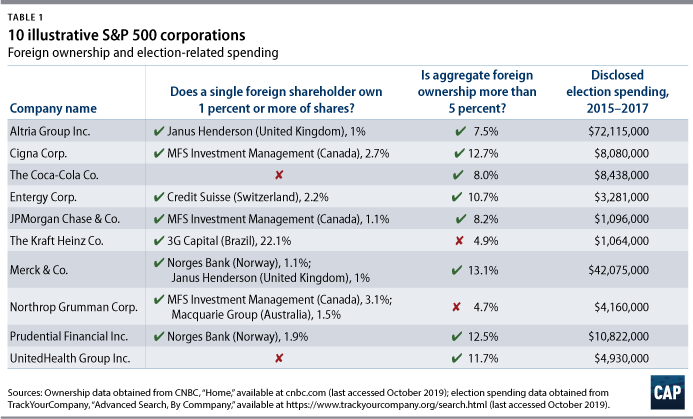

- A single foreign entity owns or controls 1 percent or more of the total equity, outstanding voting shares, membership units, or other applicable ownership interests of the corporation; or

- Multiple foreign entities own or control—in the aggregate—5 percent or more of the total equity, outstanding voting shares, membership units, or other applicable ownership interests of the corporation; or

- Any foreign entity participates in the corporation’s decision-making process about election-related spending in the United States.

These bright-line thresholds would appropriately restrict election-related spending by U.S. corporations with foreign ownership at levels potentially capable of influencing corporate governance decisions. The third prong—related to any foreign participation in corporate decision-making—is also designed to capture influence by foreign entities. For example, this prohibition could include a foreigner who sits on a corporation’s board of directors, a foreign investor who may not have requisite ownership levels but nonetheless has the power to influence corporate affairs via their relationship with corporate directors or managers, or a foreign government that enjoys the ability to exert influence over a corporation.

Foreign-influenced corporations would be prohibited from spending on any election-related communications in both federal and state elections or contributing to other organizations that engage in election-related spending. They would not be prohibited from engaging in other forms of corporate political activity, such as lobbying or spending from their corporate PACs. And individual corporate managers, executives, or employees would continue to be allowed to engage in political activity in their personal capacities. Thus, corporations and their employees would continue to have multiple ways to exercise political speech.

For this recommended proposal to robustly capture prohibited foreign influence, it must also encompass the following components:

- It must apply to all types of for-profit business forms, including but not limited to corporations, limited liability companies, partnerships, and sole proprietorships. This policy solution does not address the related issue of nonprofit corporations or other nonprofit entities.

- The term “foreign entity” must be defined to include any type of entity, including a foreign government, business, or individual. This tracks the definition of “foreign national” found in current federal law.161 The term “foreign entity” must also include any investor that may not itself be foreign but which is majority-owned or controlled by a foreign entity. For example, Company X may be owned in part by Company A, which is a U.S-based company. But if Company A is majority-owned or controlled by Foreign Entity B, then Company A is counted as a “foreign entity.”

- It must capture any involvement by foreign corporate board members and other foreigners in a corporation’s decision-making process about election-related spending in the United States.

- It must ban any spending from a corporate treasury in connection with a U.S. election, including but not limited to spending on independent expenditures; electioneering communications; contributions to 501(c)(4) and 501(c)(6) organizations, super PACs, and other similar organizations; as well as state and local ballot measures.

This recommended proposal also includes a written certification requirement. Certification would require the CEO of any U.S. corporation engaged in political spending from its corporate treasury to certify, under penalty of perjury, that the corporation is not a “foreign-influenced” corporation in violation of the prohibition on foreign national political spending, as of the date of the expenditure of corporate funds. As FEC Chair Ellen L. Weintraub has said, any credible ownership framework must require that corporate CEOs “think twice before signing off on corporate political giving or spending that they cannot guarantee comes entirely from legal sources.”162

This recommended proposal also contains a safe harbor provision. If a U.S. corporation can show that its CEO certified compliance after performing a “due inquiry” designed to meaningfully discern foreign-ownership levels, the corporation should be exempt from enforcement actions if subsequent information shows the certification to have been incorrect.163

Congress also must require U.S. businesses and their foreign investors to disclose their beneficial owners. Identifying beneficial owners would make it much harder for foreign entities to hide influence or control over a corporation’s decisions, and it would reduce the lure of using LLC shell companies to hide beneficial ownership. Well-reasoned beneficial ownership language could be drawn from provisions contained in broadly supported, bipartisan federal legislation that is pending in Congress.164 As noted expert Sheila Krumholz has testified, rigorous beneficial ownership disclosure requirements “would provide a vital tool to expose foreign kleptocrats forming U.S. companies for the purpose of influencing U.S. elections,” as well as “crucial details on the identity of those actually pulling the strings in U.S. electoral and issue campaigns.”165

In addition to beneficial owners, regulators must be required to consider ways that foreign lenders, suppliers, and other entities could use their leverage to influence or control the decision-making of a U.S. corporation.166 This leverage could arise, for example, from a third party who may control important supply chains or withhold necessary intellectual property rights.

Finally, CAP recommends that Congress consider whether to require U.S. corporations with 1 percent or greater aggregate foreign ownership to file quarterly disclosures of their election-related spending to enable appropriate oversight.

Support for foreign-ownership thresholds

At first glance, the recommended thresholds—1 percent for a single foreign shareholder and 5 percent for aggregate foreign ownership—may appear to be relatively low. However, both thresholds are solidly grounded in the practicalities of corporate governance and applicable law.

A shareholder who owns a meaningful amount of stock in a corporation can influence corporate decision-making, including decisions about political spending. But the same is true when a significant number of smaller shareholders in the aggregate have a commonality—such as foreign domicile—that can influence corporate managers’ decisions.

1 percent ownership for a single foreign shareholder

There is no universally accepted, unambiguous definition of how much ownership is necessary to qualify as a “large” or “significant” shareholder in a corporation—sometimes known as a “blockholder.”167 But as discussed below, corporate governance experts, stakeholders, and even Republican members of Congress agree that a 1 percent stockholder can wield influence in the decision-making of corporate managers.

As corporate governance expert John Coates has written, “virtually no one questions that owning 1 percent of voting shares” gives such shareholder the ability to influence corporate decision-making.168 Coates points out that “in the current corporate governance environment, the boards of companies that are confronted by 1% shareholders listen to them … they engage with them.”169 Robert Jackson, now a commissioner at the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has agreed, stating, “in the case of a 1% shareholder of a very large public company … they will be given a fair amount of attention.”170

Indeed, there is further support for this conclusion under current SEC regulations, where the threshold for presenting a shareholder proposal at a publicly traded corporation is that the shareholder must own at least 1 percent of voting shares or $2,000 of the corporation’s market value.171 In November 2019, the SEC even proposed eliminating the 1 percent threshold, finding that the vast majority of investors that submit shareholder proposals do not even have that level of equity ownership and that institutional investors below the 1 percent single owner threshold can, in fact, exercise substantial influence on a corporation’s decisions. Moreover, the SEC found that investors who meet the 1 percent threshold are easily able to communicate with corporate managers.172

Even Republicans in the House of Representatives, whose views often align with those of corporate managers, have agreed that 1 percent is a threshold at which shareholders are able to influence corporate decisions. Importantly, in 2017, during debate over pending legislation, then-Chairman of the House Committee on Financial Services Rep. Jeb Hensarling (R-TX) explained, “we have something fairly reasonable, and that is, you know, if you are going to put forward these [shareholder] proposals, have some real significant skin in the game. And what we say is one percent. One percent to put forward a shareholder proposal.”173

Chairman Hensarling even found support from the conservative-leaning Business Roundtable, an association of corporate CEOs who often advocate for management-friendly policies. During debate of the bill discussed above, the Business Roundtable supported the 1 percent threshold for individual shareholders to submit proxy proposals, and it even suggested a sliding scale that would go far below the 1 percent threshold for the largest U.S. corporations—to 0.15 percent share of ownership. The Business Roundtable also said that it supported the right of a group of shareholders to submit a proposal for consideration if those shareholders owned 3 percent of a corporation’s shares.174

Ron Fein, legal director of Free Speech For People, summed it up well when he observed that a 1 percent threshold “does not mean that every investor who owns 1% of shares will always influence corporate governance, but rather that the business community generally recognizes that this level of ownership presents that opportunity, and—for a foreign owner in the context of corporate political spending—that risk.”175 (emphasis in original)

Notably, a single shareholder threshold of 5 percent has been a commonly used metric in some settings to denote significant ownership status. Under Section 13(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended by the Williams Act, any person or group of people that acquires beneficial ownership of more than 5 percent of equity in a publicly traded corporation must publicly disclose this.176

But experts have argued that “there is no theoretical justification for the commonly-used threshold of 5%.”177 Indeed, Robert Jackson, along with noted corporate governance expert Lucian Bebchuk, has concluded that “there are many cases in which shareholders holding far less than a 5% stake were able to exert influence over a public company.”178 As examples, they pointed to a case where shareholders who owned far less than 1 percent of the stock of Massey Energy successfully urged the removal of the company’s CEO, as well as to the California Public Employees’ Retirement System (CalPERS), which commonly holds less than a 5 percent stake in most of the public companies in which it owns stock yet has influenced the companies it targets.179 The influence of a 1 percent shareholder is especially powerful in the largest publicly traded corporations, where that single shareholder may own tens of millions of dollars or more of stock.180

5 percent aggregate foreign ownership

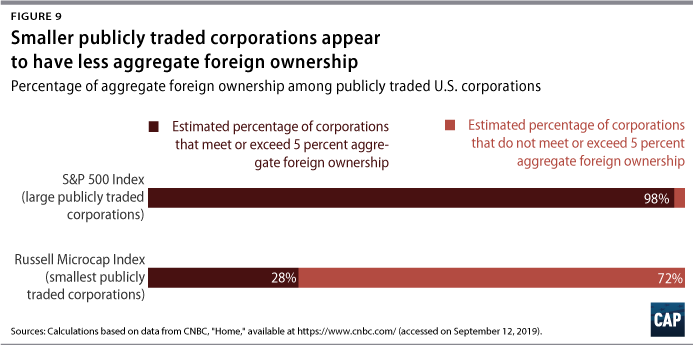

CAP’s recommended policy also employs a 5 percent threshold for aggregate foreign ownership of a corporation. This group of foreign investors could comprise foreigners who own less than or more than the 1 percent single shareholder ownership level discussed above. The operative metric measures whether 5 percent or more of the corporation’s stock is owned by shareholders of any size, no matter where they may be domiciled—as long as it is not in the United States.