A sitting Illinois Supreme Court justice could soon face questions under oath about allegations that he voted to overturn a $1 billion verdict against a powerful corporation that secretly spent millions of dollars to help him get elected.

A lawsuit now being tried in an Illinois courtroom alleges that insurance giant State Farm essentially funded and operated a multimillion-dollar campaign in 2004 to elect Justice Lloyd A. Karmeier to the state supreme court. On August 5, 2013, the plaintiffs in Hale v. State Farm told the judge hearing the case that their “stated intention” is to ask Justice Karmeier to address the allegations in a deposition. The plaintiffs contend that State Farm violated the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, or RICO, by using the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, the Illinois Republican Party, and other entities as conduits to conceal its role in funding and operating the justice’s campaign. RICO allows plaintiffs to sue persons or entities involved in a conspiracy to engage in improper activities such as bribery, fraud, or violent crimes. In May of this year, a federal judge denied State Farm’s motion to dismiss the lawsuit and ruled that the plaintiffs can continue with discovery. The trial could unearth more details about the extent of State Farm’s involvement in Justice Karmeier’s 2004 campaign.

The lessons already learned from the still-unfolding scandal are apparent. Campaign-finance reform advocates have called on state legislators to address the shortcomings of state campaign-finance laws and judicial-ethics rules in order to prevent a cataclysmic breach of justice from recurring. Such reforms are crucial to quashing the widespread belief that our judicial system is up for sale to the highest bidder.

The billion-dollar verdict

The events that form the basis of Hale v. State Farm arose in 1997, when more than 4 million aggrieved policyholders filed a class-action lawsuit in an Illinois state court against State Farm. The 1997 lawsuit—Avery v. State Farm—concerned a clause in State Farm’s automobile insurance contract that stipulated that the company would pay for replacement parts of “like kind and quality” to restore a vehicle to its pre-loss condition after an accident. State Farm was accused of breaching this promise by installing inferior replacement parts. A jury in Williamson County, Illinois, agreed with the plaintiffs in Avery v. State Farm and awarded them $1.18 billion. Although the media’s coverage of the trial played up the size of the verdict, it actually amounted to only around $300 for each of the 4 million plaintiffs.

The Fifth District Appellate Court of Illinois affirmed most of the judgment in 2001. The appellate court’s decision, authored by Judge Gordon E. Maag, lowered the total award to slightly more than $1 billion. State Farm appealed the judgment to the Illinois Supreme Court.

The Illinois Supreme Court heard oral arguments in the case in 2003, but it left the verdict pending for more than two years. In the meantime, a seat on the high court opened up in the court’s southern district. (Unlike the vast majority of states, Illinois elects its supreme court justices by districts.) The two candidates for the southern district seat were then-Judge Karmeier, a Republican circuit judge for Washington County, and Judge Maag. By the time the final votes were tallied, the 2004 Illinois Supreme Court race would become the most expensive campaign for a single judicial office in the history of the United States. More than $9 million would eventually be spent by the two candidates, with Judge Karmeier’s campaign accumulating more than $4.8 million in campaign contributions and Judge Maag amassing close to $4.6 million. A 2008 Chicago Tribune article looking back on the race noted that Justice Karmeier won “with the heavy financial assistance of business and insurance interests hoping to obtain a reversal of” the $1 billion-plus verdict against State Farm. For more reasons why the 2004 Illinois Supreme Court race may have attracted so much financial attention, see the southern district sidebar.

Illinois Southern District as the ‘class action capital’?

The American Tort Reform Association, or ATRA, is a corporate-funded organization that champions caps on damages in tort cases, restrictions on class-action lawsuits, and other limits on corporate legal liability. The group publishes an annual list of what it terms “judicial hellholes”—locales that it claims have the “worst courts in the United States.” The only apparent criterion for making this list is a perception by ATRA that a court favors injured plaintiffs over corporate defendants. Madison County, Illinois, ranked as the number-one “judicial hellhole” from 2002 to 2004. According to ATRA, Madison County was the “class action capital” of the United States in 2004, with 106 class-action filings.

When a party loses a case in Madison County, the Fifth District Appellate Court hears the appeal. The Fifth District is part of the Southern District of the Illinois Supreme Court, and the justice who represents this district has some power over appointing its lower court judges.

Corporate critics of the Madison County courts may have seen an opportunity to influence those courts through the 2004 Illinois Supreme Court election. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s Institute for Legal Reform started a newspaper covering legal affairs in Madison County, and when Justice Karmeier won the 2004 Illinois Supreme Court election, the paper proclaimed that the justice’s victory “bellow[ed]” a “resounding message.” The article quotes one observer commenting that the “dominance of Madison County in the judiciary” was a “subplot” of the election. After Justice Karmeier took his seat on the bench, Madison County fell to the fourth spot and then to the sixth spot on the judicial hellholes list in 2005 and 2006, respectively, and then it dropped from the list altogether until once again making the list in 2012.

To recuse or not to recuse?

On Election Day 2004, Justice Karmeier defeated Judge Maag by a wide margin and ascended to the Illinois Supreme Court. On the heels of Justice Karmeier’s victory, the plaintiffs in the Avery case petitioned the court to bar his participation in the case’s final decision, citing State Farm’s financial contributions to Justice Karmeier’s campaign. The plaintiffs were aware that State Farm and its employees had made direct contributions amounting to $350,000 to Justice Karmeier’s campaign and that more than $1 million had come from groups that included State Farm as a member or to which the insurance giant was a financial contributor. The Illinois Supreme Court issued an order stating that Justice Karmeier’s recusal decision was one for him alone to make. The state’s code of judicial conduct instructs Illinois judges to recuse themselves from any “proceeding in which the judge’s impartiality might reasonably be questioned,” but the rule does not mention campaign contributions as a source of questions about a judge’s impartiality. Justice Karmeier refused to recuse himself from the decision in Avery v. State Farm, and just shy of nine months after taking office, he subsequently voted to reverse the judgment against the insurer.

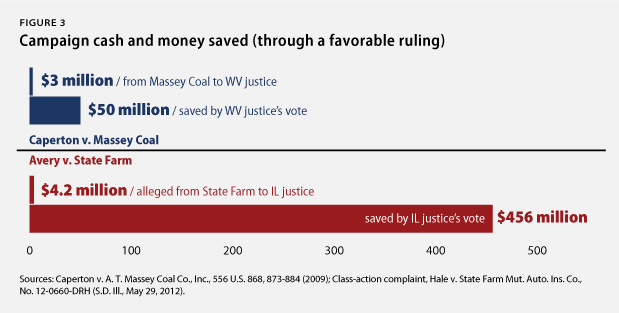

Under the Illinois Constitution, it takes four votes for the high court to overturn a lower court’s ruling. The tally in the Avery v. State Farm final decision was four justices favoring reversal and two justices partially dissenting. Absent Justice Karmeier’s participation, only the portions of the court’s opinion joined by the partially dissenting justices would have had the necessary votes to overturn the lower court’s judgment. The final vote would have been 3-2 in favor of reversing the approximately $456 million in contract damages and 5-0 in favor of reversing the $600 million in punitive damages. Without Justice Karmeier’s vote, State Farm would have still been on the hook for around $456 million. The plaintiffs in Avery petitioned the U.S. Supreme Court to weigh in on Justice Karmeier’s failure to recuse in 2006, but the Court declined to hear the case.

A constitutional right to recusal

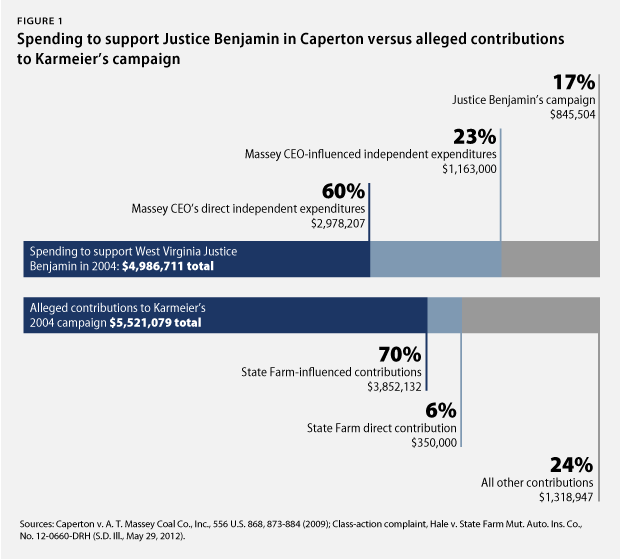

Just three years later, in 2009, the U.S. Supreme Court reviewed a legal challenge concerning a similar recusal issue. Justice Brent D. Benjamin of the West Virginia Supreme Court had failed to recuse himself from a decision overturning damages against A.T. Massey Coal Co., Inc., a major financial backer of his successful 2004 campaign. While Massey Coal’s appeal was pending, the company’s CEO gave approximately $3 million to a nonprofit corporation, which ran ads supporting Justice Benjamin and attacking his electoral opponent during the 2004 election.

In Caperton v. A.T. Massey Coal Co., Inc., a 5-4 majority of the U.S. Supreme Court held that the due-process clause requires a judge to recuse himself or herself from any cases in which there is a high “probability of actual bias.” Writing for the majority, Justice Anthony Kennedy reasoned that the Massey executive’s “extraordinary contributions were made at a time when he had a vested stake in the outcome. Just as no man is allowed to be a judge in his own cause, similar fears of bias can arise when … a man chooses the judge in his own cause.” In the wake of this decision, the plaintiffs’ counsel in Avery v. State Farm launched an investigation to determine whether State Farm’s financial involvement in Justice Karmeier’s 2004 campaign had been fully disclosed.

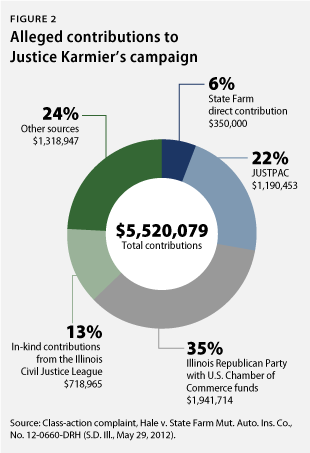

The plaintiffs claim to have uncovered additional evidence that proves that Justice Karmeier’s conflict of interest was just as significant as the conflict of interest in Caperton. As with the donations from Massey Coal, State Farm had a “stake in a particular case” that was “pending or imminent” at the time that it “rais[ed] funds or direct[ed] the judge’s election campaign.” The U.S. Supreme Court in Caperton noted that the Massey Coal executive’s spending amounted to three times the spending by the judge’s own campaign. When the secret contributions alleged by the Avery plaintiffs are added to the $4.8 million in reported campaign donations, the Karmeier campaign’s total contributions reach $5.5 million. Of this, $4.2 million—more than 75 percent of the total contributions—can be attributed to State Farm, its employees, groups to which the insurer had contributed, or groups that State Farm executives controlled. State Farm’s support for Justice Karmeier’s 2004 campaign is similar to the disproportionate financial influence of Massey Coal in electing Justice Benjamin to the West Virginia Supreme Court.

Following the money trail: Recent findings

Through the investigative work of retired FBI Special Agent Daniel Reece, the plaintiffs contend that as much as $4 million given to Justice Karmeier’s campaign came from State Farm or entities strongly influenced by State Farm executives. This newly unearthed evidence suggests that State Farm deliberately concealed the extent of its financial support for Justice Karmeier’s 2004 campaign by funneling money through a trade association, a political action committee, and a political party—all with the goal of reversing the $1 billion verdict against the company.

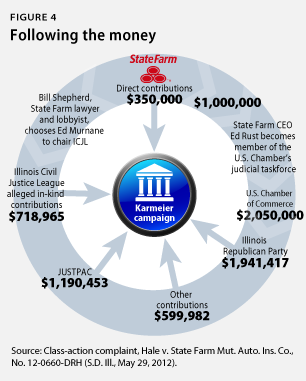

In 2004 State Farm gave the conservative-leaning, pro-business lobbying organization, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, $1 million. The chamber then contributed $2.05 million to the Illinois Republican Party. Justice Karmeier’s campaign and the Illinois Republican Party received the majority of the chamber’s judicial-campaign contributions in 2004—a full 73 percent of all contributions given to judicial campaigns on behalf of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce that year. The Illinois Republican Party gave a series of contributions totaling $1.9 million to Justice Karmeier’s campaign. Of particular note, on the same day that the chamber gave the state Republican Party $950,000, the party donated $911,282 to Justice Karmeier’s campaign.

While State Farm’s $1 million donation to the U.S. Chamber of Commerce was known in 2004, the role of State Farm’s CEO, Edward B. Rust Jr., in steering chamber funds to Justice Karmeier’s campaign has only recently come to light. The plaintiffs have uncovered evidence that Rust was part of the chamber’s task force that selected judicial races to target in 2004. As a result, the plaintiffs now contend that the $2.05 million given by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce to the Illinois Republican Party was specifically tagged by Rust for use in the 2004 Illinois Supreme Court race. The plaintiffs say that under Rust’s guidance, nearly 95 percent of the funds given by the U.S. Chamber of Commerce to the Illinois Republican Party were ultimately dedicated to Justice Karmeier’s election efforts.

Investigator Reece also claims to have uncovered evidence that prior to the 2004 election—and while Avery v. State Farm was pending in the Illinois Supreme Court—the Illinois Civil Justice League spent $718,965 to help Justice Karmeier’s campaign. The plaintiffs say that the Illinois Civil Justice League vetted and recruited candidates to run for the open seat on the court. A coalition of Illinois citizens, businesses, and associations, the Illinois Civil Justice League lobbies for limits on jury verdicts in personal-injury and class-action lawsuits. The head of the organization in 2004 was Ed Murnane. Reece’s investigation concluded that Murnane was chosen by State Farm lawyer and lobbyist William Shepherd to head the Illinois Civil Justice League in 1993.

The $718,965 in unreported, in-kind contributions from the Illinois Civil Justice League includes the cost of resources allegedly devoted to Justice Karmeier’s campaign. In-kind contributions are defined as contributions other than cash that benefit a campaign. Of these in-kind contributions, $177,749 included Murnane’s salary, benefits, and expenses. The plaintiffs claim that, “E-mails generated within Karmeier’s campaign organization unmistakably show that Murnane directed Karmeier’s fund-raising, his media relations and his speeches.” Twice in their complaint, the plaintiffs quote Murnane as saying of the 2004 Illinois Supreme Court race, “I’m running this campaign.”

While State Farm and the Illinois Civil Justice League deny this association, Reece claims to have found numerous discarded emails reportedly linking Murnane to Justice Karmeier’s campaign. One of the emails suggests that the campaign’s treasurer equated a contribution to the league’s political action committee with a contribution to the judge’s campaign. Another purportedly shows Murnane instructing the campaign treasurer not to issue press releases about fundraisers. The plaintiffs claim that the remaining unreported funds were dedicated to media, advertising, fundraising, and other managerial expenses that almost exclusively benefited Justice Karmeier.

Although this alleged spending was not reported as in-kind contributions to Justice Karmeier’s campaign, the Illinois Civil Justice League is required to report information about its expenditures. Documents filed with the Internal Revenue Service show that in 2004 the Illinois Civil Justice League spent substantially more on media buys than in subsequent years. The organization reported spending $223,658 on “media” expenses in 2004. But it reported no such spending in 2005 and only $900 in media spending in 2006. In 2007 the organization reported $49,440 in media spending. From 2008 to 2011 the Illinois Civil Justice League’s tax documents do not include much spending for “advertising and promotion,” though they include more than $100,000 in “other” expenses for each of those years. The expenditure of nearly a quarter of a million dollars on media in 2004 seems to be an outlier. Although there could clearly be another explanation for the steep drop in the organization’s media spending, the plaintiff’s allegations raise the question of whether that money was spent to help elect Justice Karmeier.

If the Illinois Civil Justice League did secretly spend nearly three-quarters of a million dollars to help elect Justice Karmeier, should those resources have been considered in-kind contributions? The Illinois State Board of Elections states that, “Goods or services provided to the campaign or purchased on behalf of the campaign must be reported as in-kind contributions.” Other large contributors to the campaign, such as the Illinois Republican Party and the Illinois State Medical Society Political Action Committee, spent their money directly on ads for Justice Karmeier, but their spending was reported as in-kind contributions. Why would the Illinois Civil Justice League fail to report its in-kind contributions when other big spenders reported them? Even JUSTPAC, a political action committee created by the Illinois Civil Justice League, reported in-kind contributions to Justice Karmeier’s campaign. Why would the league not spend this money through its political action committee and report it?

If the allegations are true, then the league’s secret spending for Justice Karmeier could not have been considered the type of independent spending that is so prevalent in judicial elections today, particularly since it appears the Illinois Civil Justice League actually recruited the candidate and then ran his campaign. The plaintiffs’ allegations suggest that the league coordinated its spending with the candidate, which independent spenders are prohibited from doing, and as such, the spending should be considered an in-kind contribution.

JUSTPAC reported spending a staggering amount of money—more than $1 million—to aid Justice Karmeier’s election efforts. These funds represent more than 90 percent of the money raised by JUSTPAC in 2004. JUSTPAC received large donations from the American Tort Reform Association, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce, and several large corporations.

With their additional evidence of State Farm’s financial influence on Justice Karmeier’s campaign—adding up to more than $4 million, substantially more than the $350,000 that State Farm’s attorneys acknowledged—the plaintiffs brought the current lawsuit in federal court. This lawsuit alleges that State Farm, Murnane, and Shepherd violated RICO through their secret involvement with Justice Karmeier’s judicial campaign. (For more information about RICO lawsuits, see the sidebar.) The plaintiffs assert that from 2003 to the present, the defendants created and conducted a racketeering enterprise designed “to enable State Farm to evade payment of a $1.05 billion judgment affirmed in favor of approximately 4.7 million State Farm policyholders by the Illinois Fifth District Appellate Court.”

Federal lawsuits help fight corruption

The federal RICO statute has been used in criminal and civil cases to hold corrupt politicians and their benefactors accountable. RICO prohibits the investment of income “derived, directly or indirectly, from a pattern of racketeering activity,” a term that includes a variety of improper activities, including bribery and fraud. The RICO statute permits victims of these activities to sue the persons involved and “recover threefold the damages he [or she] sustains and the cost of the suit, including a reasonable attorney’s fee.” As in other lawsuits, a plaintiff must also prove that he or she was injured by the RICO enterprise.

It may be more difficult to prove a legally cognizable injury resulting from corruption in the legislative context, which often harms taxpayers in general more than any specific person. But when litigants influence judges, the victims of such conflicts of interest—the opposing parties—are clear. Defendants can be held liable in RICO lawsuits if they “substantially participate” in the illegal enterprise.

Judge Maag, Justice Karmeier’s opponent in the 2004 race, also received enormous support in the form of in-kind contributions, mostly from the Justice for All Political Action Committee and the Illinois Democratic Party. Justice for All spent $1.2 million to help Judge Maag’s campaign by running ads attacking then-Judge Karmeier. In addition, the Illinois Democratic Party spent more than $2.8 million to help its candidate. Justice for All, the state Democratic Party, and Judge Maag’s campaign all received large donations from trial lawyers, including some who practice in the Southern District of Illinois.

Justice for All did not report any contributions from the lawyers representing the plaintiffs in Avery, but the Illinois Campaign for Political Reform alleged that the group received hundreds of thousands of dollars from a nonprofit entity that failed to register with the state and disclose its donors. That being the case, Judge Maag could have received funds from lawyers or law firms with cases pending before the Illinois Supreme Court or courts in the southern district. But there is no evidence that the plaintiffs’ attorneys in Avery were directly involved in Judge Maag’s campaign and no suggestion that they lied to the court about buying ads for the candidate in the 2004 election.

The claims that State Farm repeatedly lied to and concealed information from the courts about its role in Justice Karmeier’s campaign are central to the plaintiffs’ RICO allegations. The plaintiffs claim that two court documents filed by State Farm in Avery—one in 2005 and another in 2011—were fraudulent. In March 2013 the federal court threw out State Farm’s motion to dismiss the lawsuit. The court found that the plaintiffs had presented a valid claim under the RICO statute, stating:

Specifically, plaintiffs allege that defendants perpetrated a scheme to defraud plaintiffs of their property and the alleged scheme took place in two phases: (1) State Farm decided to select its own candidate for the vacant Illinois Supreme Court seat and place him on the Court to insure a decisive vote and (2) to keep the candidate on the bench despite State Farm’s support. Plaintiffs allege that State Farm used the U.S. mail to conceal these facts to permit Justice Karmeier to participate in the Avery decision and to make misrepresentations to the Illinois Supreme Court. … Based on these allegations, the Court finds that plaintiffs have alleged a set of facts and cognizable damages that are sufficient to demonstrate that defendants’ alleged acts proximately caused a loss to plaintiffs.

Lawyers for State Farm have asked the federal judge to deny class certification for the RICO lawsuit, but the plaintiffs want to move ahead with discovery, in which State Farm will have to provide information and documentation related to the alleged RICO conspiracy.

Recusal reforms to keep litigants from influencing judges

If the allegations in the Hale case are true, then State Farm evaded several anti-corruption laws for judicial races. This is a perfect example of the conflicts of interest that cause the public to doubt the integrity of elected judges. State legislators should consider reforming their judicial-recusal rules or implementing a public financing program for judicial races.

Illinois currently gives judges who are not the subject of a recusal petition the authority to decide whether a judge should be barred from participating in a case. Unfortunately, Justice Karmeier’s colleagues decided not to excuse him from the final decision in Avery, instead determining that his recusal was an issue that only he should decide. The Illinois rule on recusal instructs judges to avoid “the appearance of impropriety” or “impartiality,” but it does not require justices to consider campaign contributions when deciding whether to recuse themselves.

It may seem obvious to most observers that the contribution of hundreds of thousands of dollars—or even millions of dollars—in campaign cash from a single litigant creates an appearance of impropriety and raises concerns about a judge’s impartiality, but Justice Karmeier failed to recuse himself from the State Farm case. If the plaintiffs’ allegations are true, then Justice Karmeier knew that State Farm was paying the salary of the person running his campaign, and the RICO trial could reveal the extent to which he knew that State Farm failed to inform the rest of the court of this fact.

The adoption of mandatory recusal rules or better recusal procedures could help restore the public’s faith in the Illinois judiciary. Two committees at the American Bar Association, or ABA, have proposed changing the ABA Model Code of Judicial Conduct to include mandatory recusal rules. Leaving it to states to fill in the blanks, the proposed rule specifies that recusal is required when “a party, a party’s lawyer, or the law firm of a party’s lawyer has within the previous __ year[s] made aggregate contributions to the judge’s campaign in an amount greater than ___.” The rule defines contributions as donations from “organizations that supported or opposed the judge’s election, and all independent expenditures made directly by the party, the party’s lawyer, or the lawyer’s law firm.”

The proposed ABA-model rule applies to the types of independent expenditures that often dominate judicial elections today. But would the proposed rule require recusal for litigants, such as State Farm, that funnel contributions through third parties rather than giving money to groups for independent spending? The rule defines contributions, in part, as money given to “organizations that supported or opposed the judge’s election.” Does supporting or opposing a judge include giving the judge a direct contribution? If so, should all of a litigant’s or a lawyer’s donations to a direct campaign donor count toward recusal, or should only any portion contributed for the purpose of funding a campaign contribution count? These are questions for judges or legislators to answer when crafting ethics rules. It seems, however, that whenever a judge is aware that a litigant ran and substantially funded his or her campaign, a mandatory recusal rule should be interpreted to prevent such a conflict of interest.

The proposed ABA rule provides legislators and justices a guideline to address antiquated ethics rules that were drafted before the age of multimillion-dollar judicial campaigns and unlimited independent spending. Provisions that mandate judicial recusal for large campaign donations not only promote the fair administration of justice, but they can also help restore the public’s favorable perception of their state courts. Thus far, however, few states have adopted this ambitious standard.

Some skeptics claim that mandatory recusal rules could allow litigants to “game the system” by giving money to judges whom they do not want to hear their cases. But the proposed ABA-model rule addresses this concern by allowing litigants to waive the mandatory recusal requirement.

Critics of mandatory recusal rules also argue that such rules can get in the way of judges doing their jobs. The “rule of necessity” says that a judge should hear a case if no other judge is available, even if the judge has a perceived conflict of interest. This argument could have more force in state supreme courts, the courts of last resort for state judiciaries, than in lower courts. Some states, however, have detailed procedures that allow the chief justice to appoint a lower court judge to hear a case when a justice recuses himself or herself. Illinois could change the provision of its constitution that requires a four-justice quorum to overrule a lower court. But such an amendment would require a super-majority vote in both houses of the Illinois legislature, as well as approval by voters.

The Brennan Center for Justice, which advocated for Justice Karmeier’s recusal in Avery v. State Farm, offers the following suggestions for reforming recusal rules:

First, states should not rely on a challenged judge to make the final decision on whether his or her impartiality can reasonably be questioned. If a judge denies a recusal request, there must be prompt, meaningful review of the denial. Second, states should require transparent decision-making, including written rulings, on recusal requests. Third, states should adopt rules recognizing that judges’ impartiality may reasonably be questioned, and disqualification made necessary, because of campaign spending by litigants or their attorneys. And finally, states should require litigants (and counsel) to disclose campaign spending related to any judge or judges hearing their case.

State legislators should consider amending disqualification rules to ensure that a judge does not have the final say in whether he or she should be recused. In Illinois trial courts, litigants have one opportunity to request a different judge for any reason before any substantial rulings in the case. After that, the litigant can only request another judge “for cause,” but the judge that is the subject of the request is not permitted to decide the issue. The rules for Illinois Supreme Court justices are less strict.

Justice Karmeier’s disqualification motion was put before the rest of the high court, but his colleagues granted him the final decision on whether or not recusal was appropriate. Some states require the entire state supreme court to rule on a recusal motion, instead of allowing the court to punt the question to the justice with the alleged conflict of interest.

Alternatively, Illinois legislators could consider adopting judicial rules that subject recusal reviews or decisions to a special panel of retired judges or justices. The main goal of such panels would be to prevent the challenged justice from influencing the final decision regarding the adequacy of the recusal motion. The ABA notes that such proposals are often rejected because they impose “significant costs,” but these costs could be substantially outweighed by the benefit of increased public confidence in the judiciary. Interestingly, Justice Karmeier stated in a 2011 case involving a colleague’s recusal motion that “not only should judges not be the sole and exclusive arbiters of whether they should continue to participate in a case, some have questioned whether they should ever be permitted to sit in judgment of requests for their own disqualification.”

Legislators or justices could consider procedural rules that mandate the issuance of formal decisions responding to recusal motions and create avenues of appeal for denied motions. The plaintiffs in Avery lacked both options when they requested Justice Karmeier’s recusal, but had such safeguards been in place, they may have prevented the egregious outcome that resulted. Having judges articulate their reasoning on recusal motions allows affected parties an opportunity to have each allegation addressed in a written record. This also allows a reviewing body to weigh the relevant facts and legal arguments concerning the recusal issue. Adoption of stricter recusal rules could help repair the image of our state judiciaries and help diffuse the widespread belief that justice can be bought.

Illinois’s current recusal rules may have prevented the conflict of interest in Avery if State Farm’s connections to Justice Karmeier’s campaign had been disclosed. The proposed ABA-model rule on recusal includes a comment instructing a judge to “disclose on the record information that the judge believes the parties or their lawyers might reasonably consider relevant to a possible motion for disqualification, even if the judge believes there is no basis for disqualification.”

Illinois ethics rules currently require judges to file a detailed account of personal financial interests that could create a conflict of interest, but the rules do not require a similarly detailed account of campaign cash or independent spending that a judge knows is connected to a litigant. If a rule had required Justice Karmeier to disclose what he knew about State Farm’s efforts to get him elected, the rest of the high court may have ruled differently on the recusal motion.

Public financing can minimize the influence of large campaign contributions

In addition to shoring up recusal rules, stronger campaign-finance laws could also help keep litigants from using campaign cash to influence courts. Some states concerned about the integrity of judicial elections have implemented public financing programs, which keep candidates beholden to the public, not campaign contributors. After Massey Coal’s brazen attempt in 2004 to determine which justice would hear its appeal, West Virginia created a pilot public financing program, and in 2013 the West Virginia legislature made the program permanent.

Illinois legislators considered a bill to create a public financing system for judicial candidates in 2007, but it failed to pass the state House of Representatives. The legislation would have given a public subsidy in exchange for agreeing to spending caps and heightened disclosure requirements. Candidates would have had to qualify by raising $30,000 in “seed money” through donations of $25 or less.

A task force recently explored the various options for public financing programs for statewide candidates, including judges. The task force found that public financing for judicial candidates “could generate greater public confidence in the courts” and could be “feasible, affordable, and potentially popular” among voters.

Some public financing programs were recently called into question by a U.S. Supreme Court decision. In 2011 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled unconstitutional an Arizona public financing system that included “matching funds,” which were awarded to publicly financed candidates whenever their opponents spent more money than the amount available through the public subsidy. The Court ruled that this traditional form of matching funds was an unconstitutional “penalty” on the privately financed candidate’s speech.

The state of New York, however, is currently looking to pioneer a different type of matching-funds system that does not raise the same constitutional concerns. The state legislature is considering a small-donor matching system in which each dollar of donations under $175 would be matched with $6 in public funds. New York City has had such a system in place for municipal elections, and The Campaign Finance Institute found that it has resulted in more diverse representatives whose campaigns are funded by middle- and working-class constituents.

Such a system could have the same impact on Illinois’s high court elections. The average campaign contribution for the winning candidate in 2012, Democratic Justice Mary Jane Theis, was more than $1,000, but with small-donor matching, smaller donations would play a more important role. The task force noted that public financing could “encourage more candidates for judicial office and greater diversity among the candidates.”

Conclusion

Illinois has already taken one step toward curbing the influence of campaign cash. When Justice Karmeier was elected in 2004, Illinois had no limits on campaign contributions, which allowed State Farm to give money to organizations that then donated huge sums of money to Justice Karmeier’s campaign. Partly in response to the 2004 Illinois Supreme Court race, Illinois instituted campaign-contribution limits in 2009 aimed at preventing entities such as State Farm from funneling millions of dollars to third parties who could then contribute that money to judicial candidates.

In its 2013–2014 term, the U.S. Supreme Court will hear a lawsuit challenging the constitutionality of limits on the overall amount of money that a person or corporation can give to candidates in federal elections. For each election cycle, federal law limits overall donations to federal candidates and political action committees. Although this lawsuit only challenges overall limits and not the limits on contributions to individual candidates, Professor Richard L. Hasen of the University of California, Irvine told The New York Times that, “This could be the start of chipping away at contribution limits.” Although it might seem obvious that Congress and state legislatures should have the power to limit campaign contributions to prevent corruption, this is the same U.S. Supreme Court that ruled in Citizens United that unlimited independent spending in political campaigns does not “give rise to corruption or the appearance of corruption.”

The facts surrounding the Avery v. State Farm case prove that unlimited direct contributions to candidates have the potential to create conflicts of interest that cause the public to doubt the integrity of judges. State Farm is accused of giving millions of dollars to third parties who then gave that money to a judge hearing a case involving a $1 billion verdict against the insurance company.

More importantly, State Farm is accused of concealing these activities from the public and the rest of the Illinois Supreme Court, even though Justice Karmeier was allegedly aware of the litigant’s funding and operation of his campaign. The current RICO lawsuit can unearth the truth about State Farm’s actions.

The RICO lawsuit comes at an inconvenient time for Justice Karmeier, whose current term ends next year. Once Illinois justices are elected in a partisan, contested election, they serve 10-year terms before standing in “retention” elections, in which voters decide whether to keep them on the bench or not. While voters are considering that decision in regard to Justice Karmeier in 2014, they could learn that State Farm secretly spent millions of dollars to elect Justice Karmeier in 2004 in an effort to avoid a $1 billion verdict against itself. Without a billion-dollar verdict pending before the Illinois Supreme Court, can Justice Karmeier count on State Farm to offer similarly generous support for his 2014 retention campaign?

Illinois should act now, before there is another judicial-campaign scandal, to implement stronger rules governing judicial ethics and campaign finance. Such action could help ensure that the integrity of the court is not questioned. A poll of Illinois voters taken just after the 2004 election found that 89 percent believed that campaign contributions influence the decisions of Illinois judges to some degree. Lawmakers and the high court justices should enact new rules to minimize the influence of campaign cash on the judiciary and assure litigants that the opposing parties are not secretly influencing the judges hearing the case.

Billy Corriher is the Associate Director of Research for Legal Progress at the Center for American Progress. Brent DeBeaumont is a summer intern for Legal Progress.