Recognizing the unique role of small, community banks, lawmakers across the political spectrum have recently been debating the right way to help these institutions meet the credit needs of their communities.

Recently, financial reform opponents have seized upon the challenges facing small banks as an opportunity to launch a campaign for regulatory rollback. They claim that these rules have harmed small banks and made it unprofitable for them to lend to consumers. In the name of helping community banks, lobbyists representing a wide range of financial institutions—including both larger banks and nondepository financial institutions—have proposed a broad suite of policies that would undo many of the financial reforms and consumer protections put in place in the wake of the financial crisis to prevent similar crises in the future.

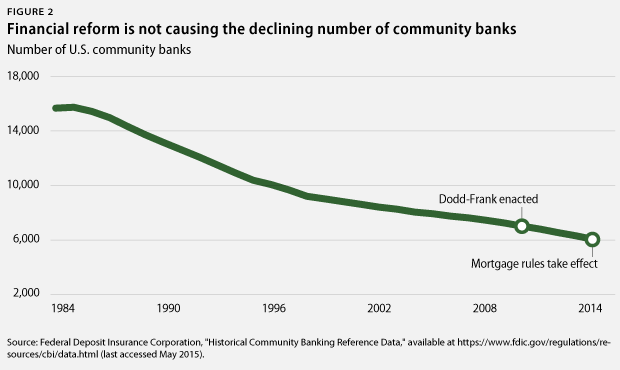

There is no question that the number of small, community banks is declining. This trend predates financial reform by decades, and the passage of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act of 2010 does not appear to have altered the pace of the decline. Reasons for this trend include basic economies of scale that drive consolidation in any number of industries, including compliance costs, as well as the increased role of technology in banking and population and economic decline in some areas where community banks operate.

Despite these challenges, most community banks have seen significant and consistent improvement in their financial performance and even have increased their mortgage and other lending in the years since Congress passed Dodd-Frank. In short, while compliance costs are undeniably high and the number of very small banks continues to decline, the specific requirements of Dodd-Frank do not appear to be the cause of the decline or to be hampering the overall performance of the sector.

However, recognizing that compliance is always a challenge for smaller institutions even when they are doing well, financial regulators already have given small banks a significant number of exemptions from the financial reform rules with which larger institutions must comply. By and large, these targeted exemptions enable small banks to meet the credit needs of their communities without weakening consumer protections or endangering the safety and soundness of the U.S. community banking sector.

In contrast, the approach to regulatory reform promoted by banking and mortgage industry lobbyists and recently passed by the U.S. Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs is not focused on community banks. Indeed, the proposed reforms would actually remove some of the competitive advantages that the current law’s tailored exemptions give smaller banks. These changes would blow a hole in financial reform and make it far more likely that there will be a resurgence of the risky lending that led to the crisis in the first place.

This brief describes the activities of community banks, identifies the challenges these banks face, describes existing regulatory exemptions, and recommends how to ensure that any regulatory reform serves the purpose of strengthening these institutions without undermining critical consumer and systemic protections.

What are community banks and whom do they serve?

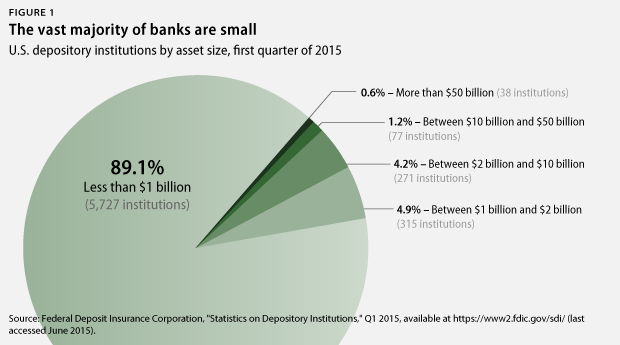

There is no single definition of a small or community bank. Generally, community banks are understood to serve narrower geographies than larger financial institutions and rely on relationship-based lending rather than automated processes. Many analysts define small or community banks based on their asset size, such as those with assets totaling less than $1 billion, as shown in Figure 1.

The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, or FDIC, has created a more nuanced definition of a community bank that takes into account its lending and deposit-taking activities and the geographic location of branches. This definition eliminates certain specialty institutions—for example, banks that primarily issue credit cards—and institutions that operate on a more national scale.

Under this definition, the FDIC deemed 93 percent of the nation’s approximately 6,400 depository institutions as community banks at the first quarter of 2015. The average community bank has approximately $340 million in assets and operates out of six offices all based in one state and one large metropolitan area.

The unique role community banks play in meeting the credit needs of communities across the country explains why they receive considerable attention from policymakers. Community banks are more likely to be located in nonmetropolitan and rural areas, which are often poorly served by larger institutions; without them, many of these areas would have limited physical access to mainstream financial services. Community banks also tend to generate their profits from core activities of taking deposits and lending, while other banks often generate large portions of their profits from activities such as trading, investment banking, and securitization.

Additionally, community banks tend to focus more heavily on agriculture and small-business lending, likely due to both their locations and their reliance on relationship-based lending, which means they often can use more flexible lending guidelines because they know and better understand their customers.

What are the problems facing small banks?

As noted above, the challenges facing community banks are long-standing issues that predate financial reform by decades. As Figure 2 shows, the number of community banks in the United States has declined at a rate of about 300 per year for the past 30 years. This rate has remained essentially unchanged in the years since Congress passed Dodd-Frank.

A primary problem for small banks is that the complexity of today’s financial market means size matters. Large banks can benefit from the economies of scale that make certain operations more efficient, while small banks cannot. The Government Accountability Office, or GAO, has concluded that, “larger banks generally are more profitable and efficient than smaller banks, which may reflect increasing returns to scale.”

A 2012 FDIC study of community banks showed that more than 80 percent of the banks that exited the industry between 1984 and 2011 left to become larger banks, either through a merger with an unaffiliated bank or consolidation with another chartered bank within the same organization. Only 17 percent of the banks that left the industry did so because they failed.

One particularly important area in which scale matters is consumer finance. For example, many smaller institutions do not offer credit cards, where the competitive advantage is gained through large-scale investments in mass marketing, data mining, and cybersecurity. Scale also matters for residential mortgage lending, which is increasingly technology driven and difficult for institutions that cannot hold large portfolios of undiversified assets. Despite these challenges, both smaller and larger community banks originate a larger share and number of home purchase mortgages today than they did in 2010.

A related concern for smaller institutions is the fixed cost of general regulatory compliance, which stems from a vast number of regulations, of which the Dodd-Frank Act is just one component. A small bank must use a greater share of resources than a large bank to update its legal disclosures or meet with bank examiners. Small banks, however, benefit from a number of exemptions from the new regulatory changes, as discussed below, and no single change in legal responsibility appears to explain the longstanding decline of these institutions.

Another challenge facing community banks is their location. Community banks are more likely to be located in nonmetropolitan and rural areas, which experience slower population and economic growth than metropolitan areas, and many of these areas suffer from severe disinvestment and underemployment. These factors may limit the prospects of the community banks that serve just these particular areas, driving interest in merging with banks that serve more dynamic locations.

Despite the challenges of scale and location, community banks as a whole have performed remarkably well, even in the years since financial reform. Data from the FDIC indicate that on important measures of performance and financial health—such as return on equity, leverage ratio, percentage of noncurrent assets, and percentage of banks that are unprofitable—community banks have seen significant and consistent improvement over the past five years.

Additionally, the vast majority of community banks are increasing the volume of loans they make—including mortgages—outperforming the industry at large. Data show that community bank earnings have grown considerably in recent quarters, despite the fact that they have had to comply with the new mortgage rules. Research from the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City indicates that as the economy recovers and interest rates increase, community banks can expect to become increasingly profitable.

Community banks already enjoy preferential treatment under financial reform rules

Financial reform legislation and the regulations that implement it already consider the unique needs of small, community banks and provide them with a broad number of exemptions and accommodations.

For example, a central component of financial reform was the enhanced supervision of large, complex, and interconnected financial institutions. Yet no institutions identified as community banks by the FDIC are subject to such supervision, and only two community banks out of the approximately 6,000 community banks are subject to the regulator-devised stress tests that monitor a bank’s ability to withstand a dramatic change in economic conditions.

Another central component of financial reform was the creation of new rules designed to prevent the risky, unsustainable mortgage lending that was at the center of the financial crisis. Under these rules, banks must underwrite all mortgages using the common-sense principle that consumers must demonstrate an ability to repay the loans.

The mortgage rules—which are implemented by the newly created Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, or CFPB—take into account the unique needs of community banks and their borrowers. Under both statutory direction and its own exemption authority, the CFPB has given these institutions the flexibility that they need to offer high-quality lending that meets the needs of their communities:

- Small banks have greater underwriting flexibility when making Qualified Mortgage, or QM, loans—those that are eligible for the highest level of protection from legal challenges—because if small banks hold the loans on portfolio, they are not bound to the fixed debt-to-income ratio limit that applies to larger lenders.

- Small institutions serving rural or underserved areas can get QM protection for loans that require a balloon payment, although the general QM definition bans balloon loans.

- The CFPB recently proposed expanding the definition of small institutions, as well as the rural definition, so that more banks would qualify for a variety of mortgage rule exemptions, including more flexibility to make QM loans. Under the new definitions, roughly 93 percent of all institutions engaged in mortgage lending would be eligible for these exemptions.

- Small institutions serving rural or underserved areas are exempt from requirements that they maintain escrow accounts for higher-cost loans.

- Small creditors are exempt from most mortgage-servicing rules.

- An array of mission-oriented lenders, such as Community Development Financial Institutions and state housing finance agencies, are fully exempt from the entire CFPB Ability-to-Repay requirement.

Smaller banks and small businesses also receive special treatment in other ways. Small businesses, for example, have the opportunity to submit early rulemaking comments to the CFPB, which is the only financial regulator subject to this requirement. The CFPB has also voluntarily created community bank and credit union advisory councils. These groups’ unique perspectives inform the CFPB during rulemaking, supervision, and enforcement. The FDIC and the Federal Reserve Board of Governors have also formed community bank advisory councils since the financial crisis.

In short, while lobbyists for the banking and the mortgage industries look to roll back financial reform by claiming that the rules make it impossible for smaller institutions to compete, it is clear that these community banks already benefit from special treatment across a wide range of rules. Furthermore, given the breadth of the exemptions and leeway they receive, smaller institutions arguably have an advantage in lending compared to larger institutions.

Whom does the Senate Banking Committee reform legislation help?

Although much of the pushback against financial reform is presented in defense of community banks, the legislation recently passed by the U.S. Senate Committee on Banking, Housing and Urban Affairs simply serves to roll back financial reforms, which would enable larger institutions to return to risky practices.

The crowning example of this Trojan horse approach is the provision that would deem almost all loans held in a bank’s portfolio as Qualified Mortgages, even if they have risky or predatory features or are only held for a short period of time. Under this new definition, lenders would be shielded from all liability for these mortgages, and they would have no legal responsibility to consider whether these loans are affordable to their borrowers. As noted above, community banks already have access to exemptions that give them more flexibility in making Qualified Mortgages when holding loans in portfolio, so this new exemption would primarily help larger institutions.

The bill would also strip critical protections for buyers of manufactured homes—many of whom are rural, lower income, and/or seniors—by raising the cost threshold for a loan to receive the enhanced protections that Congress put in place for high-cost loans, such as prohibiting balloon payments. As a result, manufactured housing residents would pay much higher interest rates before receiving the same protections that residents of site-built homes enjoy. This provision would also apply to the whole market, not just small, community banks.

Additionally, the Senate bill would impede efforts to monitor and manage systemic risk at large institutions by raising the minimum asset value at which a bank-holding company becomes automatically eligible for enhanced supervision by the Federal Reserve. The minimum asset value would increase from $50 billion to $500 billion, exempting all but the six largest bank-holding companies from requirements that make the U.S. financial system safer.

The bill would also make it harder for regulators to safeguard the financial system by imposing burdensome requirements for regulators to revisit financial protection rules wholesale on a regular basis under the Economic Growth and Regulatory Paperwork Reduction Act, even though the Dodd-Frank rules are brand new. In fact, only 60 percent of the rules under Dodd-Frank have even been finalized. The Senate bill provides financial institutions of all sizes with a path to make routine and repeated challenges to their examinations by regulators.

In short, rather than providing targeted relief for the real problems facing community institutions, these deregulatory proposals would significantly hollow out the reforms put in place after the crisis that protect against risky bank activity and predatory and dangerous loans.

An amendment from the ranking member of the Senate Banking Committee offered a more responsible approach to reform, but it lost on a party-line vote. This amendment focuses exclusively on assisting small institutions in various ways. Although it would raise the small-creditor QM portfolio exemption to institutions with up to $10 billion in assets, banks between $2 billion and $10 billion in assets would have to demonstrate that they have the characteristics and engage in the basic activities of community banks by devoting significant resources to deposit taking and lending and by operating in a limited geography.

Building on that Senate amendment, the Center for American Progress recommends considering other steps to ensure that exemptions are narrowly targeted to benefit institutions that demonstrate a commitment to meeting the credit needs of their communities. For example, there could be requirements related to a bank’s Community Reinvestment Act performance or more prescriptive numerical requirements for serving community residents.

Conclusion

In implementing financial reform, legislators and regulators already have recognized the important role that small banks play in communities across the country and the unique needs of these institutions, providing them with exemptions from requirements that apply to their larger counterparts. Legislators should therefore be skeptical of calls for further regulatory relief and should carefully consider the costs and benefits.

To the extent that data suggest specific policy changes that can help community banks address compliance costs without weakening consumer protections or endangering their safety and soundness, policymakers should pursue these reforms in a careful and tailored way. Otherwise, rolling back financial reform and consumer protections in the name of helping small banks could bring back the risky practices and predatory and unsustainable lending that led to the financial crisis and could result in additional taxpayer bailouts in the future.

David Sanchez is a Policy Analyst for Housing and Consumer Finance at the Center for American Progress. Sarah Edelman is a Senior Policy Analyst for Housing and Consumer Finance at the Center. Julia Gordon is the Senior Director of Housing and Consumer Finance at the Center.