See also: Interactive: 2016 and 2020 DAPA-Affected Voters and 2012 Margins of Victory, by State by Manuel Pastor, Tom Jawetz, and Lizet Ocampo

In the year since President Barack Obama’s November 2014 executive actions announcement, much has been written about the potential beneficiaries of these executive actions and the effect that these initiatives would have on the U.S. economy and various states. The expansion of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA, and the creation of Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents, or DAPA—together with the original DACA program that was announced in June 2012—would allow approximately 5 million unauthorized parents and DREAMers to gain temporary protection from deportation and the opportunity to apply for a work permit.

Previously, the Center for American Progress demonstrated that DACA, DAPA, and expanded DACA would dramatically raise the wages of all Americans by a cumulative $124 billion over a decade. Over this same period, the U.S. gross domestic product would increase cumulatively by $230 billion, and an average of 29,000 jobs would be created each year. Similar benefits would be realized in states all across the country. The Center for the Study of Immigrant Integration, or CSII, additionally demonstrated in a March 2015 report that increased wages for DAPA-eligible families would lift American children out of poverty—more than 40,000 children in California alone—and improve educational outcomes for these future workers and voters.

But little has been written to date about the political impact that U.S. citizen family members of DAPA-eligible individuals—an often-overlooked population—might have on future elections. By definition, many of the people who would receive protection through DAPA have children who are U.S. citizens who are now, or who soon will become, eligible to vote. Many also have other relatives and loved ones who are U.S. citizens.

This report represents the most extensive effort to date to analyze the impact that these U.S. citizen family members could have on the 2016 and 2020 elections. The report builds upon CAP’s previous electoral simulations that demonstrate that changing demographics throughout the country give voters of color in general greater potential to influence elections in key battleground states, and it uses new state-by-state projections by CSII of the number of U.S. citizens who are related to DAPA-eligible individuals.

What is DAPA?

Under DAPA, the Department of Homeland Security, or DHS, would make case-by-case decisions regarding whether to grant deferred action to certain parents of U.S. citizen children and lawful permanent residents, or LPRs. With deferred action, such parents would be protected from deportation temporarily—for renewable three-year periods, for example—and would be permitted to apply for work authorization.

To qualify for DAPA, individuals would have to meet a number of initial requirements, such as having a child who is a U.S. citizen or an LPR as of the date of the announcement and having already lived in the United States for five years. To be eligible, applicants also must not fall within any of DHS’ enforcement priorities, which include threats to national security, border security, and public safety. Finally, an individual determination must be made that there are no other reasons to deny deferred action as an exercise of discretion.

Approximately 3.7 million unauthorized immigrants could qualify for DAPA. In November 2014, the Migration Policy Institute estimated that the vast majority—more than 3.5 million—are the parents of U.S. citizens, while the remainder—an estimated 180,000—are the parents of LPRs.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services, a component of DHS, planned to begin accepting DAPA applications on May 19, 2015. But on February 16, 2015, a federal court in Texas issued a preliminary injunction barring the administration from taking any steps to implement DAPA or expanded DACA. On November 9, 2015, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the 5th Circuit upheld the injunction blocking implementation of these programs. The Department of Justice has announced that it will be petitioning for certiorari in the U.S. Supreme Court.

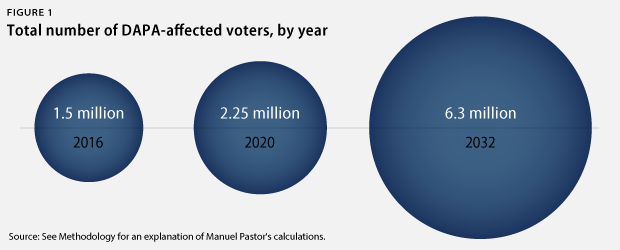

This report looks at the number of U.S. citizens of voting age who live with unauthorized family members who would be eligible for DAPA under the president’s plan—DAPA-affected voters. We estimate that 6.3 million U.S. citizens live in the same household as a DAPA-eligible relative. More than 5.3 million of these citizen family members are the children of those eligible for DAPA, and about 1 million are their spouses and other relatives. By 2016, 1.5 million of these 6.3 million citizen relatives will be eligible voters, and by 2020, that figure will rise to 2.25 million as additional children and family members reach voting age.

This report further provides state-by-state DAPA-affected voter data for 36 states. To best understand the significance of these voters, we compare the margins of victory in recent elections with the proportion of this margin that DAPA-affected voters will comprise in 2016 and 2020. For instance, President Obama won the state of Florida in 2012 by slightly more than 74,000 votes; by 2016, 80 percent of that margin of victory—nearly 60,000 votes—may be cast by DAPA-affected voters in the state, and by 2020, there will be nearly 85,000 DAPA-affected Florida voters, exceeding the 2012 margin of victory entirely.

We find that DAPA-affected voters will comprise sizable and potentially decisive portions of key and emerging battleground state electorates by 2016 and beyond. These states include both those President Obama won in 2012 and states where former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney (R) claimed victory—suggesting that they could swing either way in upcoming elections. Furthermore, DAPA-affected voters’ influence will increase in the 2020 election and beyond. To illustrate this, we focus particular attention on three states that President Obama won in 2012—Florida, Nevada, and Colorado—and three states that Gov. Romney won in 2012—North Carolina, Arizona, and Georgia:

- In 2016, DAPA-affected voters will comprise 80 percent of Florida’s 2012 margin of victory, 40 percent of Nevada’s, and 15 percent of Colorado’s. They will comprise 26 percent of North Carolina’s 2012 margin of victory, 29 percent of Arizona’s, and 11 percent of Georgia’s.

- In 2020, DAPA-affected voters will increase significantly as a proportion of the 2012 margins of victory for these states, totaling 114 percent in Florida, 60 percent in Nevada, 26 percent in Colorado, 46 percent in North Carolina, 44 percent in Arizona, and 17 percent in Georgia.

Because elections depend on voter turnout and party preference, the large number of voters in key battleground states who have a strong personal interest in a candidate’s position with respect to DAPA could have an important impact on upcoming elections. Moreover, depending upon when and whether DAPA implementation begins, the next president may have the power to either extend or terminate the initiative or to explore alternatives to DAPA that similarly offer families temporary protection from separation. This growing segment of the electorate—critical for both parties—is likely to be watching carefully how candidates from both parties talk about DAPA and the issue of immigration more broadly.

Manuel Pastor is a professor of sociology and American studies & ethnicity at the University of Southern California. Tom Jawetz is the Vice President of Immigration Policy at the Center for American Progress. Lizet Ocampo is the Associate Director of Immigration at the Center.