Introduction and summary

Federalism encourages states to act as “laboratories of democracy,” wherein states experiment with untested ideas and policies to gauge their effectiveness and potential value elsewhere, including at the federal level.1 Over the decades, state-level innovations have made dramatic improvements in the lives of millions of people in the areas of social insurance, child labor protections, and health care reform. States continue to take up the mantle of innovation by experimenting with various economic and election-related policies.2

However, this mantle of states being laboratories of democracy has not always been used for the public good. Unfortunately, states can also be used as a testing ground for policies that skew political and economic power toward corporations or billionaires and away from everyday Americans. In too many states, this is precisely what is happening today.

Across the country, conservative lawmakers are adopting policies that make corporations and billionaires richer while hurting American families. These legislators are accomplishing this by implementing irresponsible tax cuts, depriving governments of revenue for public goods and services, and making communities and workplaces less safe through deregulation and attacks on unions. To maintain power and keep bad policies in place, lawmakers further corrupt democratic processes to skew elections in their—and their wealthy donors’—favor.

Many harmful state policies are byproducts of corporate lobbying and conservative special-interest groups that act as what this report calls “corruption consultants.” In this report, “corruption” describes the exploitation and manipulation of the lawmaking process to benefit the rich and powerful. Under current law, this activity need not be illegal. In exchange for money—in the form of membership dues or donations—groups and corporations gain unprecedented access to and influence over lawmakers. For their part, overworked and underpaid state legislators are often grateful for research assistance, political advice, and networking opportunities with potential funders.3 This, in turn, leads to policies that benefit the superrich at the expense of everyone else.4

One notable example is the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), an organization funded by corporations, wealthy donors, and philanthropic foundations that serves as a hub for its funders to closely interact with state legislators.5 ALEC offers lawmakers low membership fees to incentivize them to join. Meanwhile, corporations must shell out thousands of dollars to become members.6 But they are not complaining. For corporations, ALEC’s high membership fees are well worth the cost. In addition to getting special access to and face time with legislators, corporations can draft model bills that carry out their agendas and deliver them straight to willing state legislators. ALEC is successful in part because it recognizes the importance of social ties; its corporate-sponsored conferences and retreats create opportunities for state legislators to mingle with political leaders and corporate lobbyists, generating incentives for members to come back year after year.7

ALEC is far from atypical. Another example, the Bradley Foundation—a conservative special-interest group based in Wisconsin—is believed to have exercised significant influence over former Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker’s policy agenda during his time in office.8 The group was reportedly behind the former governor’s anti-union efforts.9 Moreover, the Bradley Foundation’s former president and CEO was one of Walker’s closest political advisers.10

By using conservative special-interest groups as the conduit, corporations and billionaires can essentially buy laws that further their interests and increase their bottom lines. An investigation examining legislation at the state level found at least 10,000 instances where state legislators introduced bills drafted or influenced by special interests.11 Roughly 83 percent of bills that the study identified were tied to industry or conservative groups.

In addition to drafting legislation that favors corporations and wealthy donors, corruption consultants engage in strategic misdirection and deceptive tactics to get what they and their rich donors want.12

Dangerous policies promoted by corporations and special interests have cost everyday Americans their jobs and financial well-being, not to mention their ability to make their voices heard in the democratic process. The results of this profit- and power-driven approach to state governance has been painful for working families—particularly for employees who work in unsafe conditions. Moreover, those who are hardest hit tend to be people of color and low-income Americans.

Building off their success in conservative states, corporations and special interests are now working to export their policies across the country and to the federal level.13 After using states as a testing ground, they are seeking a nationwide takeover. In other words, those who misused the laboratories of democracies to experiment with harmful laws at the state level are scaling up.

This report brings to light how these corruption consultants have turned too many state governments into corrosive laboratories. It then offers several recommendations on how to counter that trend, including:

- Rebuilding and protecting unions as advocates for the broad-based public interest

- Unrigging elections with critical reforms to expand access to the ballot, eliminating gerrymandering, and curbing the influence of money in politics

- Ensuring that state and federal legislative offices have appropriate funding so that lawmakers do not need to rely on special-interest groups and lobbyists for support

The special-interest players driving harmful state policies

Special-interest players drive policy change with the help of conservative cross-state networks. Together, the American Legislative Exchange Council, State Policy Network, and Americans for Prosperity—what political scientist Alexander Hertel-Fernandez dubs as the “right-wing troika”—have played an important role in shaping political landscapes nationwide.14

American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC): Many state policies in place today are the brainchild of ALEC. This tax-exempt, corporate-funded organization lives by the motto “Limited Government, Free Markets and Federalism” but mainly pushes state policies that protect and put money in the pockets of corporations.15 ALEC is one of the most influential corruption consultants at the state level. As described previously, the organization serves as a conduit for businesses and conservative activists to influence state legislators. Corporate representatives and legislators sitting on ALEC’s policy “task forces” draft “model bills” on a variety of issues.16 ALEC, in turn, feeds these model bills to state legislators, along with research services and political advice.17 For state lawmakers, who often arrive in office with little experience and lack time and resources for developing policy agendas, model bills provide easy templates. Introducing legislation provided by special-interest groups also allows these groups to build rapport with lobbyists and potential political donors.18 ALEC’s lavish retreats—which are frequently paid for by its corporate members—further massage those relationships.19

State Policy Network (SPN): SPN acts as an umbrella organization for various state-based think tanks and groups that promote free market and conservative policies.20 In practice, it helps legitimize ALEC’s legislative agenda by providing research, as well as communications and advocacy support, that bolsters ALEC policies.21 Among its membership, SPN counts prominent conservative organizations such as Arizona’s Goldwater Institute, Wisconsin’s John K. MacIver Institute for Public Policy, and the Kansas Policy Institute.22

Americans for Prosperity (AFP): AFP is a political advocacy group with nearly 3 million volunteers across 35 states that deploys grassroots activism, electoral contributions, and media campaigns to advance conservative ideas proposed by ALEC and SPN.23 Founded by the Koch brothers in 2004, the group now employs over 500 paid staffers nationwide. AFP is a centerpiece of right-wing mobilization and, in recent years, has played a role in pushing for several significant conservative victories, including anti-union bills in traditional pro-labor states such as Wisconsin, Michigan, and Ohio.24

The organizations listed above are just three groups in a vast network of entities that work to manipulate the lawmaking process for the benefit of wealthy corporate interests. Other such groups include the Bradley Foundation, the Buckeye Institute, the National Right to Work Committee, the Employment Policies Institute, the American Tradition Partnership, the National Rifle Association (NRA), the Mackinac Center for Public Policy, and the Freedom Foundation.

These corruption consultants often have stated goals of promoting freedom and limited government, but in practice, this translates into policies that allow corporations to operate free from oversight and accountability. As a result, corruption consultants push an agenda that benefits corporations and the superrich while inflicting considerable harm on citizens and workers.

Economic policies driven by special interests

Across the country, special-interest groups have successfully pushed for cuts in taxes for businesses and wealthy individuals, privatization of public sector services, and deregulation of industry. The purpose of these policies is ostensibly to advance so-called free market economic ideologies. But in reality, they operate to award corporations and the superrich a privileged place in the economy, to the detriment of working families, the environment, and people of color. Corporate protectionist policies ultimately put pressure on state budgets, resulting in public revenues being slashed and workers’ rights being threatened.

This first section of the report describes strategies corruption consultants, along with corporations and conservative lawmakers, have used to bend economic rules to favor wealthy special interests. These strategies, which include tax cuts, privatization of public goods, deregulation, and attacks on unions, benefit the superrich but harm the public.

Tax cuts lead to government cutbacks of important services

Since the 1970s, conservative lawmakers and interest groups, with encouragement from wealthy donors, have promoted an anti-tax agenda. Supporters of tax cuts make the dubious claim that lower taxes allow businesses to dedicate more resources toward expanding production and investments, which they say will ultimately lead to more jobs and increased wages for American workers.25 In reality, studies of past tax cuts for large businesses and the very wealthy show that these tax cuts rarely improve the economic circumstances of most Americans.26

In fact, estimates of federal tax law changes suggest that roughly 70 percent of the financial benefits accrued from corporate tax cuts go to the wealthiest 20 percent of households.27 Corporate-backed groups such as ALEC and AFP have long pushed for similar tax cuts at the state level.28 ALEC’s armory of anti-tax model legislation includes creative titles such as the “Capital Gains Tax Elimination Act,” the “Taxpayer Protection Act,” and the “Automatic Income Tax Rate Adjustment Act.”29

Tax giveaways—which is what they are—have real repercussions for everyday Americans and state economies. State taxes fund vital initiatives in transportation, public education, and health care, just to name a few examples.30 The loss of revenue from tax cuts creates budget deficits that, in turn, require spending cuts to important programs and public services. Put simply, tax cuts result in corporations and the superrich paying less than their fair share while increasing the fiscal burden on governments and everyday Americans.

Kansas’ disastrous experiment with tax cuts provides a clear example. In 2011, then-Kansas Gov. Sam Brownback (R) began peddling what became known as the “Kansas experiment.” The experiment—designed in part by Stephen Moore and Arthur Laffer, both prominent ALEC-affiliated economists and proponents of President Donald Trump’s federal tax cuts—involved passing legislation in 2012 that instituted massive tax cuts in Kansas.31 The law reduced individual tax rates, decreased the number of tax brackets, and eliminated taxes on pass-through business income. Gov. Brownback claimed that these tax cuts would pay for themselves.32

In advocating for the tax cuts, the Kansas Policy Institute—an SPN member—claimed that they would generate at least $323 million in new revenue for local governments in the first five years.33 Yet this estimate was challenged by the Kansas Legislative Research Department, which instead projected that the tax cuts would result in a $2.4 billion deficit during the same period.34

Once the law was implemented, Kansas began hemorrhaging money. State revenues decreased by nearly $700 million—almost one-tenth of the entire state budget—after just the first year, requiring significant budget cuts with serious consequences.35 The budget cuts included siphoning away “rainy day funds” and transportation funding, delaying road projects and pension contributions, and reducing Medicaid spending.36 Moreover, reductions in education funding led to teacher layoffs, fewer school programs, and school districts being forced to end the school year more than a week early due to financial pressures.37 The private sector ultimately suffered as well in that the tax cuts did not generate the economic boom that Brownback and others had promised. In 2015, Kansas experienced negative growth in gross domestic product and, at one point, entered a technical recession when its economy shrank for two consecutive quarters.38 For several years, job growth in Kansas lagged behind the national average, as well as that of most neighboring states.39

The “Kansas experiment” ultimately proved to be a massive failure. Kansas’ Republican-controlled Legislature ultimately overrode Gov. Brownback’s veto in order to roll back the tax cuts.40 While wealthy individuals were able to take advantage of the tax cuts by becoming “pass-through entities” and lowering their tax rates, everyday citizens paid the price when the state slashed jobs and services during a critical time of recovery following the Great Recession.41

Privatization of public goods and services

Governments own, manage, or regulate certain goods and services. Utilities, health care, and education are all examples of areas where state governments are heavily involved. Privatizing these goods and services provides corporations another lucrative avenue to increase their profits. When fewer goods and services are offered by the government, there are more business opportunity for private entities. To that end, ALEC has several pieces of “model” legislation that aim to privatize a variety of public functions, including foster care and adoption services, Medicaid and Medicare, prisons, and schools.42

Proponents of privatization—namely corporate special-interest groups—argue that shifting the management of goods and services from the public sector to the private sector cuts costs and improves quality for consumers. The theory is that to compete for a limited number of government contracts, private companies will improve the value and efficiency of their products and services to win a contracting bid. However, handing control of public functions over to the private sector can result in goods and services that are less safe and of lower quality, while also increasing costs to taxpayers.43 Faced with the challenge of generating a profit, private contractors trim where possible, often skimping on labor costs by hiring nonunion and low-skilled workers, which leads to higher employee turnover and decreased security.44

For their part, corporations and private entities have major financial incentive to promote privatization schemes. For example, in 2014, prison privatization was estimated to be a $4.8 billion industry.45 Private prison companies have been a driving political force behind prison privatization and, by pushing for harsher sentencing laws, have contributed to the rise of mass incarceration, with massive implications for communities of color.46 They have used lobbying, political contributions, and close relationships to lawmakers to secure contracts with state governments.47

The privatization of public goods creates perverse incentives. Government officials with connections to corporations may engage in unethical conduct to help drive profits for their corporate friends. In the particularly egregious scandal dubbed “Kids for Cash,” a private juvenile detention center paid two judges in Pennsylvania millions of dollars to sentence young people to their facility, allowing the private company to earn higher profits.48 As noted by The Washington Post, “The influence of private prisons creates a system that trades money for human freedom, often at the expense of the nation’s most vulnerable populations: children, immigrants, and the poor.”49

Florida, in particular, has been a hotbed of prison privatization. Today, several adult prisons and all juvenile residential programs in the state are owned and operated by private corporations, with one of the nation’s largest private prison companies headquartered there too.50 When Florida began privatizing prisons in the early 1990s, proponents claimed that it would improve service quality and reduce recidivism, all while decreasing costs and increasing efficiency.51 However, research shows that incarcerating people in private prisons does not save jurisdictions money and can even be costlier than government-run facilities.52 There is also no evidence that private prisons are more successful in reducing recidivism than government-run programs.53 Making matters worse, private prisons tend to be less safe for incarcerated people compared with government-run facilities.54 Security concerns are exacerbated by a lack of transparency and accountability. For instance, because private prisons often do not comply with Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests and state public record laws, it can be difficult to track bad behavior and build a case against companies that run private facilities.55

The privatization of prisons is just a glimpse of efforts by corporate special interests to take over public functions. Additionally, corporate-aligned entities have succeeded in expanding private school voucher programs by more than 500 percent over the past decade and now educate more than 450,000 students across the country.56

Private school vouchers divert state budget funds away from public education systems toward private schools backed by corporate and special interests.57 These programs are not subject to the same level of oversight and education standards as public schools.58 In many states, participating private schools do not administer the same assessments as public schools, making it difficult for parents to gauge how their children are performing relative to statewide standards.59 Recent studies of multiple statewide programs have also shown that private school vouchers can increase socio-economic and racial segregation in schools.60

In 2011, the SPN-affiliated Goldwater Institute and the American Federation for Children—a group founded by current Secretary of Education Betsy Devos that focuses on private school vouchers—backed Arizona’s creation of Empowerment Scholarship Accounts. This type of private school voucher program, also known as education savings accounts, provides funds directly to families to pay for tuition or other educational services.61 Initially, these accounts were only offered to children with special needs; however, a series of eligibility expansions made it clear that the Arizona Legislature’s true intent was to crack open the door to universal private school vouchers.62

Audits of the Empowerment Scholarship Account program uncovered a spate of controversies over fraudulent spending, and Arizona voters ultimately rejected lawmakers’ bid to extend them to all 1.1 million students in the state.63 Beth Lewis, co-founder of a nonpartisan group that advocates for strong public schools in Arizona, said, “This result sends a message to the state and the nation that Arizona supports public education, not privatization schemes that hurt our children and our communities.”64

Deregulation

Government regulations exist to keep people safe and corporations honest. They work to prevent America’s water sources from being polluted and to ensure that companies aren’t using carcinogenic chemicals in products. They also help keep financial institutions from cheating customers while maintaining the safety of the nation’s food and medications.

Corporations and conservative special-interest groups argue that government regulation stymies productivity and innovation while forcing companies to waste resources to comply with government rules.65 The truth, however, is that companies like deregulation because it often increases their ability to access markets while shielding them from government oversight and legal liability. Too often, the result is higher corporate profits at the expense of consumer safety.

Over the years, ALEC, at the behest of industry groups and its corporate members, has pushed deregulation efforts in states, including legislation that would prevent municipalities from regulating the use of tobacco, guns, and environmentally harmful plastic bags.66

Some large telecommunications providers have spent millions lobbying lawmakers at all levels of government to prevent and roll back government regulations dictating basic quality-of-service requirements and anti-monopoly directives.67 The deregulation of internet and cable service providers has resulted in significant headaches and problems for everyday Americans.

Telecom deregulation enables major telecom companies to provide shoddy service while simultaneously gouging consumers with high prices.68 These companies create local fiefdoms wherein consumer residents are left with limited service providers to choose from, thereby empowering companies to further drive up prices and reduce quality.69 These consequences fall disproportionately on low-income people, people of color, and people in rural communities.70

In more than 30 states throughout the country, legislators backed by large telecom companies have introduced bills that “strip states of any enforcement power over service quality and prices.”71 In 2012, lawmakers in California passed a law that eliminated the California Public Utilities Commission’s ability to require reliable internet service quality in rural areas.72 This raised red flags for advocacy groups, given the history of some telecom providers providing lower-quality services to rural areas and tribal lands.73

Deregulatory efforts, led by corporations and special interests, also extend to the energy sector. The oil and gas industry, for instance, actively promotes legislation that would preempt municipalities from banning hydraulic fracking. Local governments have raised concerns that fracking can lead to groundwater contamination, reductions in property value, and increased seismic activity.74 Because of these concerns, almost 550 localities nationwide had passed anti-fracking laws as of April 2017.75 But when Denton, Texas, moved to become the first city to ban fracking in Texas in 2014, the Texas Oil & Gas Association—a pro-industry group—used its influence with state lawmakers to squelch the city’s efforts.76 Within a few months, the Texas House of Representatives passed a bill—co-authored by ALEC national chairman and state Rep. Phil King (R)—prohibiting localities from regulating oil and gas activities, including fracking.77 Beyond Texas, fracking preemption bills have been introduced or passed in roughly half a dozen other states.78

Attacks on public unions

Unions provide workers—especially LGBTQ workers and workers of color—critical protections and a voice at the workplace, as well as a powerful avenue to advocate for their economic rights.79 By encouraging members to participate in politics, aggregating the small-dollar donations of workers into meaningful political contributions, and advocating for worker interests in political battles, unions also help to ensure that government works to protect the interests of ordinary Americans, instead of just those of corporations and the superrich.80 Research shows that where unions are stronger, politicians are more likely to represent the political preferences of low-income Americans and the middle class.81

Indeed, in the advocacy positions that they take on economic topics outside of collective bargaining rights—such as tax policy, financial regulation, and trade policy—unions are often the advocacy group most closely aligned with the broader public interest and are sometimes one of the few groups with actual political heft to counter corporate and Wall Street interests. This dynamic was most notably on display in the fight to regulate Wall Street following the 2008 financial crisis, when union expertise and political heft was essential in establishing a Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, regulating derivatives, banning proprietary trading, and passing and implementing a strong financial reform bill overall.82

It should not be surprising, then, that union-busting has been a priority for corporations and corporate-backed special-interest groups—such as the National Right to Work Committee and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce—for decades.83 In advocating on behalf of workers, unions help employees obtain fair wages, along with health insurance, sick pay, and safe working conditions. By eliminating unions, corporations can skirt their responsibility to provide workers with basic benefits and living wages. Corporate boards have a fiduciary duty to maximize the profits of their shareholders, and spending less on employees allows for higher profit margins, which make shareholders and corporate boards happy. For their part, conservative lawmakers have been more than willing to go along with anti-union efforts since research suggests that union mobilization acts as a check on conservative political power.84

Efforts to disempower unions are not limited to the private sector. Corruption consultants such as ALEC have also sought to eliminate unions in the public sphere.85 In addition to all the traditional gains provided by unionization—including better benefits and safer workplaces—public sector unions help to address the enormous pay disparities between public and private sector workers.86

Conservative lawmakers and special interests claim that anti-union policies are necessary for reining in rampant government spending in the public sector. However, the real aim is to reduce the power of public workers and thus weaken resistance to their unpopular economic policies.87 Indeed, some political strategists appear to view the assault on unions as, at least in part, a way to defund their political opposition.88 SPN’s president and CEO has openly admitted that the aim of anti-union efforts is to “defund and defang” government unions; ultimately, the goal is to “deal a major blow to the left’s ability to control government at the state and national levels.”89

In Wisconsin, shortly after taking office, then-Gov. Scott Walker (R) implemented cutbacks to public sector bargaining rights with help from the SPN-affiliated Wisconsin Policy Research Institute and MacIver Institute.90 The 2011 bill—known as Act 10—virtually eliminated collective bargaining for most state and municipal employees, including K-12 teachers.91 Act 10 barred public sector employees from bargaining over working hours, conditions of employment, and even compensation beyond base pay, with base pay increases capped by rates of inflation. The bill also significantly weakened unions by requiring annual recertification elections and by prohibiting unions from using payroll deductions to collect dues.92

Walker claimed that the budget bill was necessary to address deficits, but Wisconsin residents were not buying it. Instead, they staged a series of massive protests against the bill in the state capitol and at other locations across the state. Kevin Gibbons, a union leader representing teaching assistants, said at the time, “I think Governor Walker is using this financial crisis as an excuse to attack unions, and if Wisconsin goes, what will be next?”93 And William B. Gould IV, a noted labor law professor, gave the following ominous warning: “I think it’s quite possible that if they’re successful in doing this, a lot of other Republican governors will emulate this.”94

Public polls at the time indicated that Wisconsin voters opposed Walker’s efforts to strip unions’ negotiating rights, but conservative-interest groups across the state rallied to push the bill anyway.95 Shortly after Walker’s election, the MacIver Institute published an editorial on its website arguing in favor of repealing collective bargaining rights for public employees;96 and they, together with AFP, later spent at least $4.5 million on ads lauding the misleadingly named “budget repair bill”—and its cuts to collective bargaining—as a success.97 During the legislative battle, Americans for Prosperity mobilized Walker supporters from across the state to demonstrate in favor of Act 10 in the state’s capital city of Madison.98

Despite claims that the bill would improve educational outcomes by giving schools the “additional flexibility needed to attract and retain higher-quality teachers,” research shows that Act 10 lowered salaries and benefits and led to increased turnover rates among teachers.99 Moreover, the share of teachers with low levels of experience increased.100 After Act 10’s passage, public union membership plummeted by more than 50 percent, leading to smaller union budgets and fewer funds to invest in state and local elections.101

Efforts to undermine democracy

Constituents who are frustrated with or harmed by detrimental policies enacted by lawmakers may seek to remedy the problem by electing new representatives who will put their interests above those of corporations and superrich donors. But to prevent this from happening, conservative lawmakers, with the help of wealthy special interests, have created significant barriers in the democratic process to ensure that they hold onto power and that their policies remain in place.102

They accomplish this by implementing harsh election measures, such as strict voter ID requirements and reduced voting hours, that make it hard for certain groups—namely people of color, low-income Americans, and young people—to make their voices heard. By pushing for racial and partisan gerrymanders and facilitating massive pay-to-play donations from corporate donors, conservatives further skew and corrupt election outcomes.103 Much of these changes occur at the state and local levels, turning the affected states and communities into laboratories of corruption.

Given that people of color, young people, and low-income Americans tend to lean Democrat,104 some conservative Republican-led states have targeted these specific groups through voter suppression and anti-democratic measures.105 Corporate special interests also have an incentive to suppress these groups, since Republican lawmakers are often more sympathetic to their interests than Democrats.106 For their part, Democrats in some states have adopted partisan gerrymanders that skew election results in their favor as well.

Both Democratic and Republican lawmakers receive large contributions from corporate donors and special-interest groups.107 However, corporate special interests tend to favor Republicans.108

When their attempts to suppress American voters fail, politicians have circumvented democratic norms to retain power. This was demonstrated in the wake of the 2018 elections. After Democratic candidates were elected to governorships in Wisconsin and Michigan in November 2018, the Republican-controlled legislatures in those states passed a slew of bills to curb the incoming governors’ authority.109 Their goal: To prevent the new leaders from overhauling harmful policies.110 These midnight-hour, lame-duck power grabs were unabashedly anti-democratic and violated the trust of voters who had chosen new leadership for their respective states. Similar tactics have been employed previously in North Carolina, while the South Dakota and Florida legislatures circumvented pro-democracy ballot initiatives approved by the states’ voters.111

This section of the report details the ways in which lawmakers—with the help of special-interest groups—have sought to undermine democracy in order to retain power and prevent their policies from being overturned.

Attacks on voting rights

Although states are required to abide by certain federal laws relating to voting, they have broad authority in setting the rules and carrying out elections.112 Some lawmakers have taken advantage of their broad authority in positive ways by adopting affirmative voting policies that improve voter participation, such as automatic voter registration and same-day voter registration.113 Others, however, have gone in the opposite direction with negative results for democracy.

A resurgence of voter suppression emerged in the aftermath of the 2013 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Shelby County v. Holder, which invalidated the Voting Rights Act’s federal oversight formula.114 Previously, jurisdictions with histories of discriminatory voting practices were required to submit electoral changes to the federal government for review prior to implementation. After Shelby County, these jurisdictions could do whatever they pleased with little fear of quick reprisal.115 The Supreme Court’s decision was catastrophic. In its aftermath, a wave of restrictive voting laws were enacted across the country—predominantly in states with troubled civil rights histories.116

Among the most common voter suppression measures are polling place closures in communities of color, the elimination of early voting, and reduced voting hours.117 Beyond this, some states have engaged in mass and discriminatory voter purges, ignored the accessibility needs of voters with disabilities, and failed to provide resources and aid for eligible voters with limited English proficiency.118 And most notably, strict voter ID requirements continue to be pushed through legislatures by conservative politicians who perpetuate myths of widespread voter fraud. Each election cycle, voter ID requirements prevent countless eligible Americans from making their voices heard.119 These laws disproportionately affect people of color, low-income Americans, people with disabilities, and young people.120 For example, during the 2018 midterm election, a strict voter ID law in North Dakota threatened to disenfranchise an estimated 5,000 Native Americans.121

Some strict voter ID laws are the product of ALEC model legislation.122 Because ALEC’s conservative legislative members tend to lean Republican, the organization has an interest in keeping Republican politicians in power for its own preservation. It is therefore unsurprising that ALEC and other similar groups advance policies that prevent likely Democratic voters from participating in elections. Tellingly, Paul Weyrich, co-founder of both ALEC and the Heritage Foundation, once said, “I don’t want everybody to vote … As a matter of fact, our leverage in the elections quite candidly goes up as the voting populace goes down.”123

One particularly egregious example of state-level voter suppression is North Carolina’s “monster” voting law, which was struck down by a federal court in 2016 for targeting “African Americans with almost surgical precision.”124 Adopted in 2013, the law eliminated early voting and same-day registration and required voters to present limited forms of ID prior to casting a ballot, among other harmful measures. North Carolina legislators touted the law as necessary for preventing fraudulent voting.125 But in a 2013 interview, a North Carolina GOP precinct chairman made a series of controversial comments about the law, such as: “The law is going to kick the Democrats in the butt … if it hurts a bunch of lazy blacks that want the government to give them everything, so be it.”126 The chairman eventually resigned. A North Carolina Republican consultant also said of the law: “Look, if African Americans voted overwhelmingly Republican, they would have kept early voting right where it was … It wasn’t about discriminating against African Americans. They just ended up in the middle of it because they vote Democrat.”127 A new voter ID law in North Carolina will be in place for the 2020 elections.128

Voter suppression laws, such as strict voter ID and cuts to voting opportunities, are peddled by conservative special interests and their allies in the legislatures as essential for protecting the integrity of elections. In reality, they are a nothing more than tools to prevent voters from electing their preferred candidates and kicking out of office lawmakers who work at the behest of special interests.

Gerrymandered maps

Voting district lines are redrawn roughly every 10 years, typically after each census. Specific processes for redrawing maps vary across states, but in many places, it is the legislators who are responsible for determining district lines.129

Some lawmakers manipulate district lines in ways that ensure that they remain in power.130 They do this by “packing” communities of color and certain other voters into a small number of districts, while creating safe districts and districts with more modest majorities to benefit their own political parties. Through racial and partisan gerrymandering, politicians can choose their voters, instead of the other way around.131

Gerrymandered districts betray the foundational principle of fair representation. Beyond this, they result in bad policy outcomes that hurt everyday Americans. Gerrymanders insulate incumbents from accountability, thereby allowing politicians to ignore the will of voters and enact policies that are good for special interests but antithetical to public opinion.132

In 2011, lawmakers in Wisconsin redrew the state’s district maps to ensure that their party could retain supermajority control even if they lost the statewide popular vote in future elections.133 As a result, legislators made harmful policy choices without regard for voters’ preferences, including by blocking Medicaid expansion despite majority public support for it.134 During the 2018 elections, Democratic state assembly candidates received 190,000 more votes than Republican candidates. But because of gerrymandering, Republicans still ended up securing a majority—63 of 99 seats—in the state assembly.135 During the 2019–2020 legislative session, the Wisconsin legislative majority has maintained its refusal to expand Medicaid, leaving some residents without access to affordable health care.136

In other places, gerrymandered legislatures—Democratic and Republican—have prevented certain policies, even though majorities of voters approved of them.137

Although some gerrymandered maps have been struck down by courts in recent years, others remain in place. This is thanks, in part, to special-interest organizations who hamstring efforts to make the map-drawing process fairer.138 For example, Protect My Vote, which was backed by the conservative Michigan Freedom Fund, spent $1.2 million in 2018 as part of an effort to defeat a Michigan ballot measure that would create fairer district maps.139 Another group, Citizens Protecting Michigan’s Constitution—backed by corporate interests—also engaged in activities to prevent redistricting reform from appearing on Michigan’s 2018 ballot.140 At the same time, ALEC has waged campaigns to prevent judges from taking steps to fix gerrymandered maps.141

On June 27, 2019, in a 5-4 decision, the U.S. Supreme Court held that federal courts cannot intervene to fix partisan gerrymandering.142 The ruling severely hampers the ability for individuals to challenge district maps that unfairly favor one political party over another. In her dissent, Justice Elena Kagan expressed that she was writing “with deep sadness,” going on to say: “Of all times to abandon the Court’s duty to declare the law, this was not the one … Part of the court’s role in [the U.S. system of government] is to defend its foundations. None is more important than free and fair elections.”143

Big-money politics

Political campaigns are expensive and require funding to compensate staff and to communicate the candidates’ messages to voters. As a result, politicians rely heavily on their donors to keep their campaigns afloat and get elected or reelected. Many donors are large corporations and wealthy individuals, some of whom give money in exchange for VIP access to politicians and as part of a broader strategy to influence policy in their favor.144 Everyday Americans cannot compete with millionaire donors, resulting in politicians who are beholden to wealthy special interests instead of their constituents.

This big-money system provides massive political and financial payoffs for corporations and wealthy donors. It should therefore come as no surprise that these groups have played instrumental roles in preventing commonsense campaign finance reform from being enacted. For example, Americans for Prosperity and other Koch-backed groups have taken credit for blocking campaign finance reform in several states, including New Mexico, Minnesota, and Georgia.145

In addition to campaign contributions, corporations and special interests spend significant amounts on lobbying lawmakers and government employees to adopt policies that benefit their interests. Through lobbying, corporate special interests have the ears of lawmakers. Lobbyists shower elected officials and staff with expensive gifts, fancy dinners, and political fundraising soirees in an effort to influence lawmakers and obtain more favorable policies. As described by political scientist Lee Drutman, corporate lobbying has “fundamentally changed how corporations interact with government—rather than trying to keep government out of its business (as they did for a long time), companies are now increasingly bringing government in as a partner, looking to see what the country can do for them.”146

Most states lack strong lobbying restrictions and campaign finance regulations. Seventeen states permit corporations to give unlimited amounts of money to both political parties and political action committees (PACs); 41 states allow lobbyists, corporate or otherwise, to fundraise for politicians.147

Consequently, corporations, special-interest groups, and superwealthy donors flood the system with campaign contributions, political advertisements, and lobbyists. Since the early 2000s, the NRA has spent more than $124 million on elections and more than $6 million on lobbying.148 The Koch-backed group Americans for Prosperity has similarly spent millions on elections and lobbying activities, as have a wide range of brand-name companies.149 According to the National Institute on Money in Politics, the Western States Petroleum Association, which represents oil and gas companies, spent more than $8 million on state lobbying activities in 2017.150

As noted, corporations pursue multiple strategies to influence the lawmaking process, including through lobbying, political contributions, and outside spending. It is hard to imagine that these efforts have not had a corrupting influence on politicians and lawmakers. As just one example, in 2017, a state representative in Texas introduced a bill that would have licensed a detention center belonging to one of the country’s biggest prison corporations as a child care facility to hold migrant families.151 The bill was reportedly authored by the prison corporation itself. Investigations have found that migrants held in private detention facilities have been subjected to abuse and unsafe conditions.152 The prison company involved also provided political contributions to the state representative, who, in 2018, was elected as judge in a county that houses two of the company’s facilities.153 As described by Mother Jones reporter Madison Pauly: “[In Texas, the prison company] directed about $25,000 toward elections for county commissioners and judges in districts where the company operates immigration detention centers … Such local politicians are often involved in making lucrative immigration detention deals in which counties act as middlemen between private prison companies and the federal government.”154

Montana as a case study for corporate corruption in elections

The history of Montana’s Corrupt Practices Act provides an extreme example of corporate influence in elections. The act was passed as part of a 1912 ballot measure to address widespread corruption in Montana’s political system.155 The source of this corruption came primarily from wealthy copper barons and corporations—such as the Amalgamated Copper Company, otherwise known as the Anaconda Copper Company.156 Copper barons and respective company men used a whole host of tricks to rig elections and control politicians. During the 19th and early-20th centuries, these corporate wrongdoers used their immense political influence over state legislators to secure the passage of pro-monopoly legislation and to block bills that would have increased taxes on mining companies and establish workers compensation. They also bribed judges for favorable rulings and used newspapers that they owned to manipulate the public discourse. As if this wasn’t enough, company men were embedded into political party delegations, while workers were reportedly pressured by their superiors to cast votes for pro-business candidates.157

The Corrupt Practices Act was designed to stamp out Montana’s culture of corruption by prohibiting corporate expenditures. Although it was a positive step forward, as described by Professor Jeff Wiltse in his article “The Origins of Montana’s Corrupt Practices Act: A More Complete History,” the copper companies ultimately “found new and ingenious ways to influence the state legislature.”158 In fact, the Anaconda Copper Company established a service whereby it drafted and fed corporate protectionist legislation to state lawmakers, establishing itself as an early precursor to groups like ALEC.159

The Corrupt Practices Act was challenged in the aftermath of Citizens United v. Federal Election Committee, wherein the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that corporations had a right to spend unlimited amounts of money on independent campaign ads.160 Pointing to its unique history of corporate corruption, Montana argued that its prohibition against corporate spending should be allowed to stand even in light of the court’s ruling.161 The conservative justices on the Supreme Court disagreed, stating in a per curiam opinion that the law fell squarely within the purview of Citizens United.162

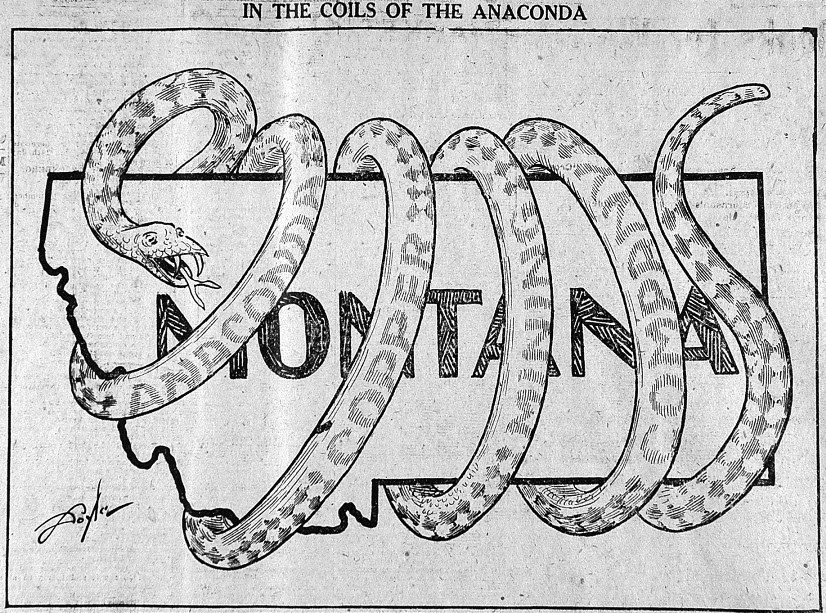

“In the coils of the Anaconda,” Butte Daily Bulletin, October 2, 1920

The spread of dangerous policies across states and at the federal level

As described in previous sections, corporations and special-interest groups have been successful in getting policies enacted at the state level that overwhelmingly benefit them and their bottom lines. With help from sympathetic lawmakers, these powerful entities have manipulated the democratic processes to their benefit.

They know that the ideas they put forth are bad for the broader public. The negative effects of the policies described in previous sections of this report on individuals and state economies are well-documented and widely reported. This, however, has not stopped corporate special interests from spreading and promoting these ideas. After using individual states as testing grounds, harmful policies are being exported to other jurisdictions.

According to the Sentencing Project, as of 2016, 27 states contracted with private prisons to house justice-involved individuals.163 Moreover, 29 states and the District of Columbia have private school voucher programs,164 and 28 states have right-to-work laws.165 The Bradley Foundation, after testing its ability to influence lawmaking “in the political petri dish of Wisconsin,” is now spending millions of dollars to peddle dangerous anti-labor policies in states such as Colorado, Washington, and Oregon.166 Again, with Wisconsin as a model, several other states have sought cuts to collective bargaining for public sector employees.167 Furthermore, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures, 10 states now require voters to show some form of strict voter ID prior to casting a ballot.168

Corruption consultants do not just help export policies; they also export ideas. The Liberty Justice Center—an SPN affiliate in Illinois—provided legal support for the Supreme Court’s anti-union 2018 decision in Janus v. AFSCME; and several other SPN affiliates filed amicus briefs on behalf of plaintiff Mark Janus.169 In the wake of Janus, public sector unions nationwide may no longer require nonmembers to pay dues or “fair share” fees, even when those workers benefit from union-bargained contracts and job protections.170 This opens the door for “freeriding” and reduces the incentive to join unions, since workers can now receive benefits without paying the cost of negotiating for them.171 The Supreme Court’s decision to weaken unions will have long-term consequences for working Americans and will likely affect electoral outcomes, since unions are often credited with driving political participation among their members and communities in support of pro-worker candidates and causes.172

By using their vast wealth and influence, special-interest groups and corporations have learned that they can skew economic policy in their favor and make it harder for voters to remove corrupt politicians from office. Having experienced success at the state level, they are employing these same tactics at the federal level.

Wealthy donors go to great lengths to influence federal lawmakers, and they seem to be reaping the benefits at the federal level. In 2018, Congress passed a massive tax bill that provided huge giveaways to corporations and billionaires—many of whom have made political donations to members of Congress—despite numerous polls showing that the public did not support such tax cuts.173 This is not surprising, however, considering that members of the congressional committees responsible for writing federal tax bills have cumulatively received more than $1.5 billion in political contributions from corporate PACs and corporate employees over the course of their careers.174

These members of Congress faced immense pressure from their wealthy donors. Rep. Chris Collins (R-NY) said of the tax bill, “My donors are basically saying, ‘Get it done or don’t ever call me again’.”175 Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-SC) also warned his party that if it failed to pass the tax bill, “the financial contributions will stop.”176 Special-interest groups got involved too. The American Action Network—a conservative dark money organization that receives funding from corporations and industry groups—spent more than $27 million on media advocacy from July 2017 through June 2018 in support of the tax cuts and other conservative policies.177

Groups backed by corporate and special interests such as the National Association of Business Political Action Committees, FreedomWorks, and the Conservative Action Project, have also attempted to thwart H.R. 1, the “For the People Act.”178 In addition to preventing voter suppression, H.R. 1 would prohibit racial and partisan gerrymandering, and implement various campaign finance reforms to help mitigate corporate and special-interest influence over elections.179 Although H.R.1’s provisions apply specifically to federal elections, they would have a significant impact on election administration at the state level.

Knowing these reforms would limit their control over the political process and threaten corporate protectionism at the state and federal level, conservative special interests have strongly opposed the bill.180 Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY), who has amassed considerable power under the currently skewed system, has said he will not even allow H.R. 1 to be brought up for a vote in the Senate.181

Another way corporate special interests promote their agendas is through the federal judicial appointment process. Decisions made by federal judges have severe repercussions for workers and individuals across the country. In addition to curtailing the power of unions, federal judges have restricted the ability to bring class action lawsuits, which are relied upon to address institutionalized discrimination and corporate misconduct.182 Judges have also facilitated the rise of forced arbitration agreements, which require consumers and workers to have their claims heard in business-friendly arbitration, rather than in front of a neutral judge.183 Furthermore, the Supreme Court has empowered lawmakers to engage in voter suppression and for wealthy individuals to funnel billions of dollars into elections.184

Conservative dark money groups, including the Judicial Crisis Network (JCN) have spent millions on campaigns to secure the appointment of federal judges who are sympathetic to corporate and conservative interests. After spending $7 million to prevent then-President Barack Obama’s choice for the Supreme Court, Judge Merrick Garland, from even receiving a hearing, JCN spent upwards of $10 million to secure a seat for Neil Gorsuch when Trump took office.185 Since being appointed to the Supreme Court, Justice Gorsuch has voted to cripple unions and prevent individuals from bringing cases against abusive companies to court. In addition, JCN spent an estimated $3.9 million on television advertisements in support of Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s appointment to the court.186

The Center for American Progress and other groups have documented the corporate takeover of the federal judiciary and its detrimental effect on economies and democratic processes.187 After being appointed, judges backed by special interests have curtailed mechanisms for corporate transparency and accountability while simultaneously destroying important voting and campaign finance protections that keep elections fair and help to ensure that politicians are accountable to their constituents, rather than big-money donors.188

Recommendations

In the battle for control over U.S. democracy, the American people are losing. The reins of government, at both the state and federal level, have been handed to corporations and wealthy special interests who put profits above everyday Americans.

There are a number of substantive policy solutions that can strengthen America’s economies and make them fairer at all levels of government. For example, past CAP and CAP Action reports have proposed numerous policy recommendations to address this problem. CAP Action’s “Unions Make Democracy Work for the Middle Class” describes the importance of unions as a countervailing force, while “10 Ways State and Local Officials Can Build Worker Power in 2019” outlines how state and local officials can build union capacity by involving worker organizations in workforce training, public benefit provision, and the enforcement of workplace laws.189 Additionally, “State and Local Policies to Support Government Workers and Their Unions” describes how progressive leaders can strengthen public sector unions, for instance, by modernizing union communications and dues collection.190 Meanwhile, a CAP report, “America Can Do Big Things: A Budget Plan for a Better Future,” demonstrates how rebalancing the tax code so that the wealthy and corporations pay their fair share could fund broadly supported policies such as ensuring that all families have access to affordable health care and child care and investing in infrastructure, science, and schools.191 Finally, “Ending Special Tax Treatment for the Very Wealthy” explains how the U.S. tax system contributes to income and wealth inequality and what changes are needed to fix this growing problem.192

But first, America’s broken political system must be fixed.

This involves unskewing elections through reforms that prevent corporations and special-interest groups from exercising undue influence over the electoral process. This will help to ensure that all Americans—regardless of wealth or connections—can make their voices heard and elect lawmakers that will represent the will of the people.

One option is for states and the federal government to establish campaign finance systems centered on small-donor matching and voucher programs, as detailed in CAP’s report “The Small-Donor Antidote to Big-Donor Politics.”193 Programs such as these allow candidates to run for office without depending on contributions from special interests and big corporate donors. As an added benefit, they help to ensure that every American—including those with limited or no disposable income—can donate to candidates of their choice. This will result in more women, people of color, and younger people running for office.194

To ensure that every eligible American has access to the ballot box, robust pro-voter policies must be established at both the state and federal level. This means repealing strict voter ID requirements and banning mass and discriminatory voter purges. It also entails ensuring that polling places are accessible and that eligible voters are given ample opportunity to cast ballots through extended voting hours and early voting. Same-day voter registration, automatic voter registration, and preregistration for 16- and-17-year-olds also help facilitate voter participation—particularly among historically underrepresented groups. Additionally, with the 2020 census quickly approaching, states will have the opportunity to undo gerrymandered maps. A new CAP report, “Voter-Determined Districts,” argues that maps should be drawn not to serve the interests of politicians, but to reflect the political preferences of voters.195 If 50 percent of a state supports a particular party, then 50 percent of the seats in that state’s legislature should be filled by candidates from that party.

A number of these important reforms are included in the historic For the People Act, which passed the U.S. House of Representatives earlier this year, and which states can look to as a guide for adopting their own pro-voter reforms.196 Unfortunately, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-KY) and his allies refuse to even consider the legislation.

The electoral reforms detailed above are critical to keeping U.S. elections fair. Strong policies are also needed to keep politicians honest once they attain office.

For example, as detailed in previous CAP reports, legislative committee members should be prohibited from accepting contributions from entities whose interests they oversee.197 After leaving office, they should also be permanently barred from taking jobs as lobbyists. Put another way: The revolving door should be closed. Promises of lucrative lobbying careers can lead lawmakers to provide favors to corporations and industries while in office.198 Other important reforms include prohibiting lobbyists from fundraising for politicians and enacting stronger campaign finance disclosure laws, so that voters know who their representatives take money from.

State and federal legislative offices must also have appropriate budgets to support and hire staff. Inadequate budgets result in legislative offices being understaffed and underresourced. This leads legislators to rely on special-interest groups and lobbyists to assist them in crafting legislation and lending expertise.199 By building up internal capacity within legislative offices, special-interest influence will be severely weakened.

Finally, significant changes must be made to federal judicial appointment and recusal processes. The perception that judicial appointments are being influenced by special-interest groups threatens public faith in the institution as well as the courts’ credibility. Parties that come before the court should have full confidence that the judge hearing their case is a neutral arbiter, rather than someone working at the behest of the secret groups and donors who secured their appointment. Additionally, strengthening recusal requirements and enforcement mechanisms would prevent judges from showing favorable bias toward corporate entities in which they have financial interests. Steps should also be taken to strengthen ethics requirements and to limit the ability of partisan judges to hold too much sway over judicial decisions. CAP’s report “Structural Reforms to the Federal Judiciary” describes these reforms in greater detail.200

Conclusion

In manipulating the lawmaking process, corporations and special interests have, at times, caused serious damage to state economies and democratic systems. Through the use of corruption consultants, these well-heeled and influential players appear to be more intent on helping themselves become richer and more powerful than on generating ideas that help everyday Americans.

To curb these entities’ influence over elections and elected officials, strong reforms at the state and federal level are needed to fix broken political and economic systems. This requires a complete revamping of America’s voting and electoral system, as well as significant structural changes to the federal judiciary and congressional ethics standards. It also requires boosting worker power, enhancing and restoring the public interest-oriented information and analysis available to lawmakers. By taking these steps, lawmakers can be more responsive to constituents and pass robust, substantive policies to revitalize public services, boost worker power, and restore crucial protections for the public—which, in turn, would further build support for an inclusive democracy. And by ensuring that these policies incorporate the needs of all Americans, control of the “laboratories of democracy” can be returned to the people and out of the hands of corporate special interests.

About the authors

Malkie Wall is a research assistant for Economic Policy at the Center for American Progress.

Danielle Root is the associate director of Voting Rights for Democracy and Government at the Center.

Andrew Schwartz is a former senior policy analyst of Economic Policy at the Center.