Luis Rivera has spent the past two decades struggling to find stable, family-sustaining work. Although he was released from prison in the 1990s after serving a two-year sentence, his criminal record still casts a long shadow over his employment prospects. As a result, Rivera has spent most his life piecing together dead-end, informal, and part-time jobs, and trying to support a family of four while earning minimum wage.1

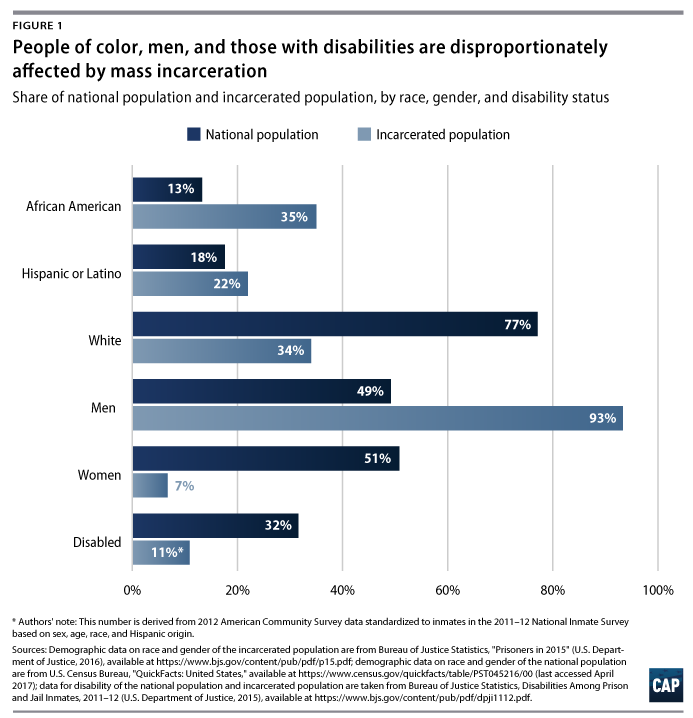

Rivera’s story is unfortunately far from unique. Today, as many as 1 in 3 Americans have a criminal record.2 This has meant that each year, millions of people with criminal records struggle to find good jobs that make it possible for them to support their families and move on with their lives.3 For people of color and those with disabilities, who face overwhelmingly disproportionate rates of incarceration, a criminal record is yet one more obstacle to employment in a labor market that already discriminates against these groups.

The challenges Rivera and millions of others in similar circumstances face do not need to be inevitable. Governments at all levels can take steps to improve the labor market attachment of the formerly incarcerated—beginning while they are still behind bars. Apprenticeship programs for the incarcerated, which combine on-the-job training with relevant classroom instruction, could significantly improve employment outcomes for returning citizens. This is especially true if participating inmates are earning wages for their time on the job. This brief argues that greater access to paid prison apprenticeship programs could effectively improve inmates’ post-release outcomes, particularly for a group of individuals who already face significant barriers to labor market entry.

Obstacles to re-entering the labor market

The formerly incarcerated face numerous obstacles to re-entering the labor market upon release. Lower levels of educational attainment; the stigma of incarceration; a lack of employment history or long periods of unemployment; and a criminal record all increase the prospect of unemployment.

Certain populations, such as people of color and those with disabilities, are disproportionally affected by mass incarceration. (see Figure 1) African Americans, for example, represent 13 percent4 of the national population while representing a startling 35 percent of the incarcerated population.5 Additionally, although women make up a small share of the incarcerated,6 African American women are overrepresented, making up 21 percent of incarcerated women7 but only 13 percent of women nationwide.8 Decades of policies promoting mass incarceration have disproportionately ensnared these groups in the criminal justice system.9

The stigma associated with having a criminal record affects nearly one-third of the U.S. adult working-age population.10 Roughly 60 percent11 of the almost 650,000 inmates12 released from prison each year are unemployed one year after release. Having a criminal record can be an immediate barrier to employment. Research shows that employers are 50 percent less likely to hire or extend a callback to someone with a criminal record.13 Additionally, data indicate that unemployment is not just a short-term effect of incarceration: It can continue to be a barrier years after release. Even five years post-release, 67 percent of the formerly incarcerated remain either unemployed or underemployed.14

The stigma of having a criminal record is especially harmful to those who are parents; nearly half of U.S. children now have a parent with a criminal record.15 The effects of having a criminal record are also substantially more injurious for African Americans, who are 50 percent less likely to receive a callback or job offer than someone with a criminal record who is white.16

There is a clear need for policies and programs that help inmates gain employment post-release. Research indicates that meaningful employment soon after release is key to former inmates’ long-term success. A 2008 Urban Institute study examining employment outcomes for the formerly incarcerated found that employment post-release decreases the likelihood of recidivism, particularly if it is secured shortly after release and is well-paying.17 The study found that the higher the wages earned by formerly incarcerated individuals two months post-release, the less likely it was that those individuals would return to prison eight to 10 months after release. For example, individuals who made more than $10 an hour were 50 percent less likely to return to prison than those making less than $7 an hour.18

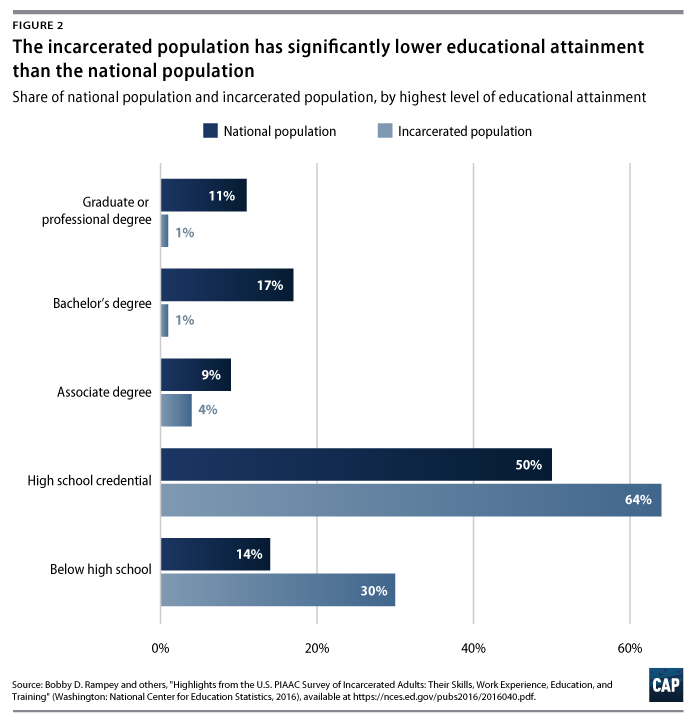

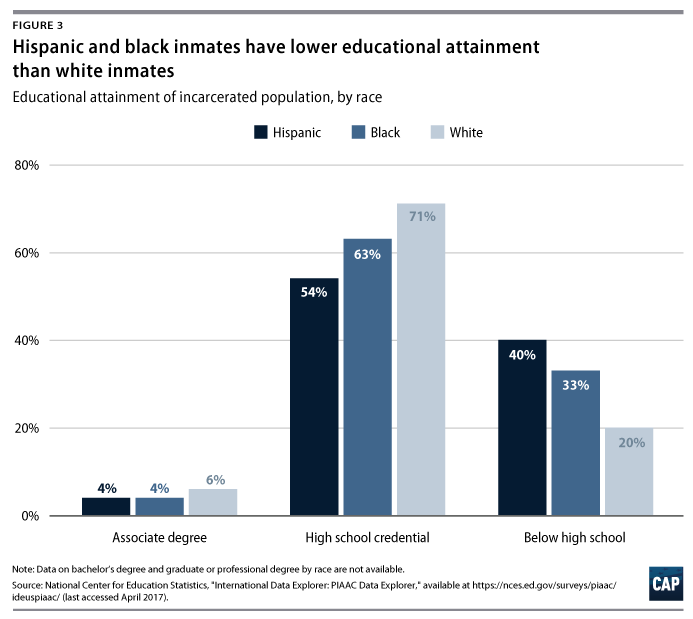

Educational attainment is a barrier to employment as well. Individuals who are incarcerated have lower levels of educational attainment, putting them at greater risk of unemployment once they are released. A startling 94 percent of incarcerated people have a high school diploma or less, while only 64 percent of the U.S. adult population is in the same position. (see Figure 2) Among African Americans, this figure rises to 96 percent. (see Figure 3) What’s more, 37 percent of the U.S. adult population holds an associate degree or higher, while only 6 percent of the incarcerated population holds the same degree. (see Figure 2)

Research suggests that prison education programs, including apprenticeships and other vocational and academic programs, are successful in reducing recidivism and improving inmates’ labor market outcomes post-release.19 A 2013 study found that incarcerated individuals who participated in prison education programs were 43 percent less likely to return to prison than those who did not participate. Additionally, those who participated in vocational training programs were almost 30 percent more likely to be employed after release than those who did not receive training.20

Despite promising research on the positive impact of prison education programs, educational opportunities within prison are scarce and have decreased over the past few decades.21 A 2002 study by the Urban Institute found that inmate participation in vocational training declined from 31 percent to 27 percent between 1991 and 1997, and that participation in educational programs declined by seven percentage points—from 42 percent to 35 percent—over the same period.22 One factor contributing to this decline was Congress’ 1994 decision to remove inmates’ access to Pell Grants. This led to a 44 percent decrease in participation in postsecondary educational programs within just one year and the closure of about half of existing postsecondary education programs in correctional facilities.23

The decline in prison education and vocational programs was further precipitated during the 1990s and early 2000s due to the rapid increase of the prison population; decreased federal funding for prison education programs; frequent transferring of inmates from one facility to another; and a greater focus on short-term substance abuse and anger management programs.24 More recently, during the Great Recession, states significantly decreased spending on prison education programs with the sharpest cuts occurring in states with the most inmates.25

There has been recent progress: In 2015, the U.S. Department of Education announced it was launching a pilot program to test whether access to financial aid causes more incarcerated people to participate in postsecondary education programs while incarcerated. However, the pilot is limited to only a small fraction of federal and state facilities nationwide.26

Working while incarcerated

Many people work while incarcerated. More than half27 of the 1.5 million28 individuals incarcerated in state and federal facilities work while in prison. According to the most recent prison census, the vast majority—74 percent—of participants work in facility support, while others participate in public works assignments or prison industries.29

Employment assignments in prison

Facility support

The most common type of prison work is facility support.30 Inmates who work in facility support perform various maintenance chores, such as cooking, cleaning, laundry, cleric work, and more.

Public works assignments

The second most common type of prison work is public works assignments.31 Through public works assignments, inmates work for state or local governments on projects in the public interest, such as picking up trash, tending to parks, or construction on public buildings.

Prison industries

A small share of inmates work in prison industries that produce goods for government use.32 The federal prison industry is known as UNICOR, but states often have their own prison industry programs.33

Individuals who are incarcerated are not statutorily exempt from the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, or FLSA, which requires employers to pay most workers at least the federal minimum wage.34 However, the courts have generally ruled that such workers are excluded from FLSA protections.35 In interpreting who is covered under the FSLA, the test applied by the courts is to determine if an employment relationship exists between the two entities. Since inmates can be forced to work under the 13th Amendment, and prisons do not have usual employer rights such as hiring and firing, courts have generally ruled that inmates and prisons do not constitute an employment relationship.36 As a result, the overwhelming majority of incarcerated workers are either unpaid or paid well below the minimum wage.37 Those who do earn a wage are often paid little more than a few cents an hour—raising human rights concerns about the exploitation of free labor.38

Apprenticeships offer a solution

Where prison work programs fail to offer opportunities for participants to learn skills that will be valuable in the labor market, apprenticeships, which offer paid on-the-job training, may be the solution.39 These programs could improve individuals’ job prospects post-incarceration, thus lowering the chance of recidivism.

In 2016, more than 200,000 workers throughout the country started Registered Apprenticeship, or RA, programs—paid on-the-job training programs that are registered with the U.S. Department of Labor, or DOL—in industries ranging from construction to computer science.40 What is less well-known is that on average, more than 8 percent of RA entrants each year are individuals who are currently incarcerated.41 Apprenticeships are unique in that they offer training and work experience that will be valuable to individuals upon their release. Given how successful these programs have been for workers more broadly, they may offer a promising way to help incarcerated individuals secure a good job upon release.42

Apprenticeship programs are characterized by extensive learning on the job under the supervision of an experienced worker and supplemented by some classroom instruction. Apprenticeship programs typically consist of 2,000 hours of on-the-job training along with a recommended minimum 144 hours of classroom instruction annually, according to the DOL. Importantly, apprentices are paid for their time on the job and receive incremental wage increases based on time or skills mastery.43 Upon completion, each apprentice graduates with an industry-issued, nationally recognized credential from the DOL.44 Research commissioned by the DOL shows that these programs are proven to increase participants’ wages and provide job opportunities.45

Apprenticeships have a long history in the United States, and thanks to recent interest from policymakers, these programs are experiencing a resurgence. In 2014, then-President Barack Obama announced a national goal to double the number of apprentices nationwide in five years.46 Since then, the number of apprentices has increased by 23 percent.47 The momentum around apprenticeship programs is likely linked to their impressive stats: a 91 percent post-program employment rate and an average annual starting wage of $50,000 upon program completion.48

Apprenticeships help alleviate barriers to opportunity

Apprentices represent a small but growing share of the working prison population. Since the 2005 corrections census was conducted, the number of incarcerated apprentices has increased by almost threefold. In 2016, more than 9,000 incarcerated individuals enrolled in apprenticeship programs.49

Apprenticeships offer the incarcerated population the opportunity to gain valuable skills and a credential that is marketable in the broader labor market. Additionally, apprenticeship programs allow incarcerated individuals to connect with potential employers. Ideally, these programs should help inmate apprentices connect with outside employment opportunities—by partnering with local unions and employers to help connect inmates with jobs prior to release. In addition to the DOL certificate, some apprentice programs offer opportunities for participants to earn industry certifications while incarcerated.50 In some cases, the programs will award transcripts to apprentices who have completed a certain percentage of their program before release, which can be used with outside employers to demonstrate competency.

The Iowa Department of Corrections, or DOC, has experienced success with its recently implemented apprenticeship program. In 2014, the state’s DOC transitioned existing prison industry jobs into apprenticeship programs. Today, it sponsors 19 registered apprenticeships across their nine facilities.

The majority of the state’s apprentice programs are run through Iowa Prison Industries in occupations such as cabinet making, metal fabrication and welding, screen printing, and computer operations. Since 2015, program participation has increased by more than 700 percent, and the program currently has 277 registered apprentices. Since starting the program, 71 apprentices have completed it. The DOC is working on collecting employment data on all completed apprentices, which will likely be available in the fall. The DOC also works with employers, unions, workforce development boards, and other organizations to help participants secure gainful employment after release.

As noted above, job-specific training programs such as apprenticeships increase the likelihood of employment post-release by 30 percent and decrease the likelihood of recidivating significantly. For example, the Indiana DOC found that those participating in their prison apprenticeship programs were almost 30 percent less likely to return to prison within three years of release than those who did not participate in program.51 These findings, along with the findings of a 2012 DOL-commissioned report that concluded the RA program was cost-effective and increased the earnings of participants, suggest that the RA program for inmates would produce similar results.52

Despite data indicating that inmates want to participate in job training programs, few prisons currently offer them. A study by the National Center for Education Statistics, or NCES, found that only 7 percent of inmates received certificates from a college or trade school while incarcerated, while 29 percent of respondents wanted to obtain these certifications. Again, according to the NCES survey, 39 percent of inmates who indicated they wanted to enroll in an educational program gave as their main reason to do so a desire to “increase the possibilities of getting a job when released.” That same survey found that 23 percent of inmates reported having participated in a jobs skills or job training program during their current incarceration, while 14 percent were on a waiting list for entering a job training program.53 Expanding apprenticeships will help fill this need and more—providing inmates with the job training and work experience to gain employment post-incarceration.

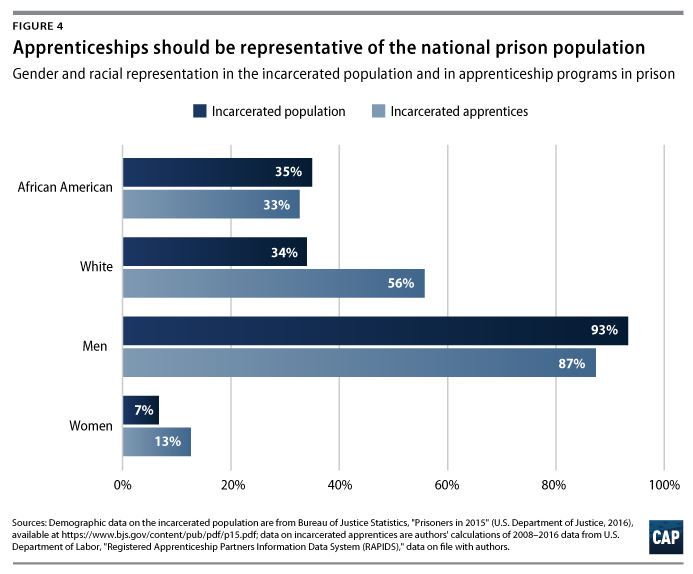

Apprenticeship programs may be even more beneficial for individuals who face multiple barriers to labor market entry, such as racial or other forms of discrimination. Greater access to prison apprenticeship programs could help these individuals improve their skills and obtain a credential that holds value in the labor market, which in turn could help mitigate other barriers to labor market re-entry. Apprenticeship programs—although often male-dominated because they are concentrated in the male-dominated building and construction trades—hold great potential for female inmates as well.54 While women make up just 7 percent of the incarcerated population in the United States, they represent 13 percent of incarcerated apprentices. (see Figure 4) If these programs are made more available to women who are incarcerated, it can help these women enter well-paid and traditionally male-dominated fields, such as construction, upon release.

Apprenticeships are promising—but must pay fair wages

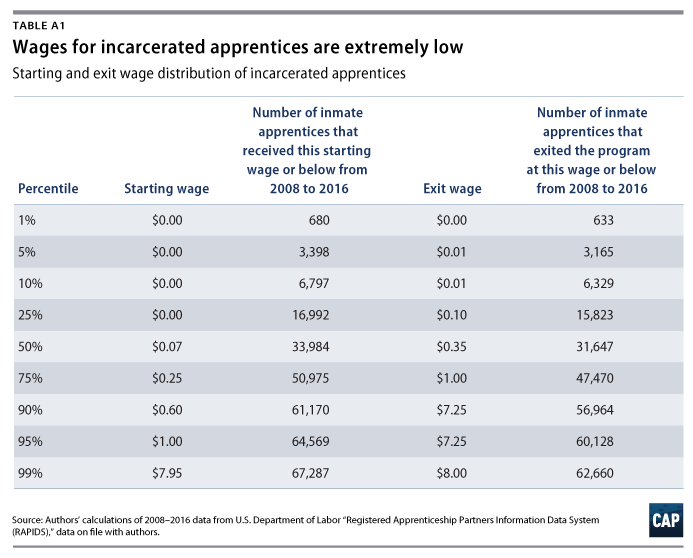

While prison apprenticeships show promise, as currently designed, they suffer the same fundamental flaw as other prison work programs: They are either unpaid or pay well below the minimum wage. In fact, the median starting wage of inmate apprentices from 2008 to 2016 was 7 cents an hour and the median exit wage was 35 cents.55 (see Table A1 for full wage distribution) By comparison, the average annual salary for an individual who completes an apprenticeship is slightly more than $50,000.56 In reality, median wages may be lower than what is reflected here since some states deduct a share of inmate’s wages for a variety of purposes, including court fines, victim reparations, and family support. These deductions leave incarcerated workers with an even smaller share of their meager pay.57 Moreover, many programs do not pay apprentices at all. In 2016, 4,800 inmate apprentices started their apprenticeship with no pay and almost 4,900 ended their programs without pay. This has translated to more than 30,000 unpaid new incarcerated apprentices since 2008.58

Paying inmate workers at least the minimum wage is not a novel concept. In fact, the Prison Industry Enhancement Certification Program, known as PIECP—which is available to a small share of inmates—already pays inmates the prevailing wage.59 Unfortunately, high deductions mean that these workers also take back very low wages. 60

Prison apprenticeships would be much more beneficial to apprentices if they paid better wages. The formerly incarcerated often find hefty financial burdens waiting for them upon release. Furthermore, many face significant court fees and fines accumulated during incarceration that can push them into debt.61 Returning citizens also face the challenge of returning to families that have suffered financially as a result of that individual’s incarceration, due to the loss of family income or to the lack of child support. 62 Indeed, 2 in 3 families of incarcerated individuals reported difficulty meeting basic needs because of a family member’s incarceration, and almost 20 percent of families with incarcerated members were unable to afford housing due to the loss of income resulting from their family members’ incarceration.63 Paying inmates could help keep their families afloat financially while they are incarcerated.

Conclusion

Returning citizens face many barriers to re-entering the labor market upon their release. Apprenticeships can help smooth this difficult transition by equipping returning citizens with real-world, in-demand skills that can improve employment and earnings prospects going forward and reduce the likelihood of recidivism.

To be clear, apprenticeships are not a panacea—they cannot wholly alleviate the discrimination that the formerly incarcerated, especially individuals of color and people with disabilities, face in the labor market. Other policy changes, such as fair chance hiring, record-clearing, inmate access to Pell Grants, and other criminal justice reforms are badly needed as well. But apprenticeships do offer one policy solution for putting a more secure future within reach for returning citizens and their families.

While the number of apprenticeship programs in prisons is growing, they are still too rare in America’s massive correctional system. Policymakers should expand access to apprenticeship programs for incarcerated individuals by investing in strategies to develop high-quality apprenticeship and pre-apprenticeship programs. At a minimum, high-quality programs should have relationships with outside employers and unions to help establish connections to jobs upon release. Policymakers should also consider amending the FLSA to explicitly include incarcerated workers, to ensure that they are paid at least the minimum wage for apprenticeships and other forms of prison work. Additionally, although certain apprenticeship programs have collected data on post-release employment and recidivism of those who have gone through the programs, the DOL should standardize this data collection across all apprenticeship programs.

As America begins to come to terms with the damage the carceral state is exacting on its citizens—disproportionately people of color and individuals with disabilities—paid apprenticeships for inmates offer an evidence-backed plan to give newly released individuals the skills and experience they need to secure gainful employment once they return to their communities. These apprenticeships benefit not only inmates but also their communities, since returning citizens will have the skills to be productive members of their community. Policymakers should take note.

Appendix

Administration of the Registered Apprenticeship program in the United States

The DOL’s Office of Apprenticeship administers the RA system. As noted in a CAP report, “Training for Success,” the system consists of a national office, six regional offices,64 and local offices in each state.65 The Office of Apprenticeship directly administers the program in 25 states and delegates some operational authority to state apprenticeship agencies in 25 states and the District of Columbia.

The Office of Apprenticeship is responsible for:

- Program approval and standards

- Program and apprentice registration

- Worker safety and health

- Issuing certificates of completion

- Ensuring that programs offer high-quality training

- Promoting apprenticeships to employers

State apprenticeship agencies devote most of their resources to approving new occupations for apprenticeship and on program and apprentice registration with the DOL.66 All apprenticeships culminate in a nationally recognized certificate issued by the DOL.67

Annie McGrew is a Special Assistant for the Economic Policy team at the Center for American Progress. Angela Hanks is the Associate Director for Workforce Development Policy on the Economic Policy team at the Center.