Last week, the U.S. Energy Information Administration, or EIA, released its Annual Energy Outlook 2015, which examines energy-market trends and makes forecasts up to 2040. Adam Sieminski, the EIA administrator, stated that “advanced technologies are reshaping the U.S. energy economy” and creating the potential for the United States to eliminate net energy imports by 2030.

This raises an important question: How has this energy transformation affected the potential trajectory of carbon pollution in the United States?

Energy-related carbon pollution—that is, pollution from the combustion of fossil fuels in the electricity, transportation, residential, consumer, and industrial sectors of the economy—comprises the majority of greenhouse gas emissions in the United States. According to the EIA, energy-related carbon pollution fell 10 percent between 2005 and 2013 as a result of the “substitution of natural gas for coal in electricity generation, increases in the use of renewable energy, improvements in vehicle fuel economy, and increases in the efficiencies of appliances and industrial processes.” That’s the good news.

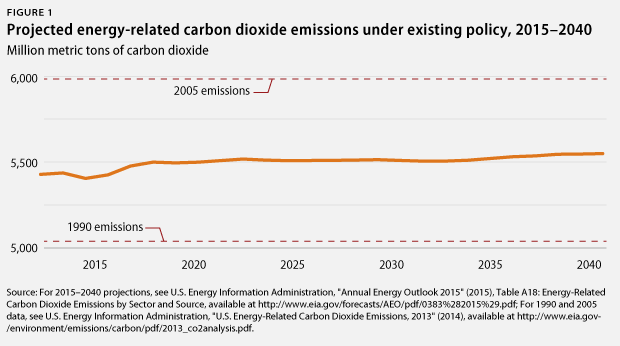

Unfortunately, this trend is unlikely to hold if the United States proceeds with business as usual. The EIA estimates that energy-related carbon pollution increased 0.7 percent in 2014. Assuming that the United States does not implement any new policies to curb carbon pollution—including the Environmental Protection Agency’s, or EPA’s, Clean Power Plan—the EIA predicts that through 2040, energy-related carbon pollution in the United States will grow by an average of 0.1 percent per year. By 2040, energy-related carbon pollution will be 1.1 percent higher than it was in 2014. (see Figure 1)

Without the Clean Power Plan and other smart climate policies, energy-related carbon emissions are poised to move incrementally upward instead of where they need to go—steadily downward.

This trajectory is far out of step with what the world’s leading climate scientists say is necessary to avoid the worst impacts of climate change. They argue that greenhouse gas emissions from developed nations such as the United States need to decline 80 percent to 95 percent by 2050 compared with 1990 levels. In contrast, the EIA predicts that if the United States does not implement controls on carbon pollution, energy-related carbon emissions will be 7.5 percent below 2005 levels by 2040 but 10 percent higher than 1990 levels. (see Figure 1)

The new EIA data highlight the importance of the Clean Power Plan, which is designed to clean up one major source of energy-related carbon emissions: power plants.

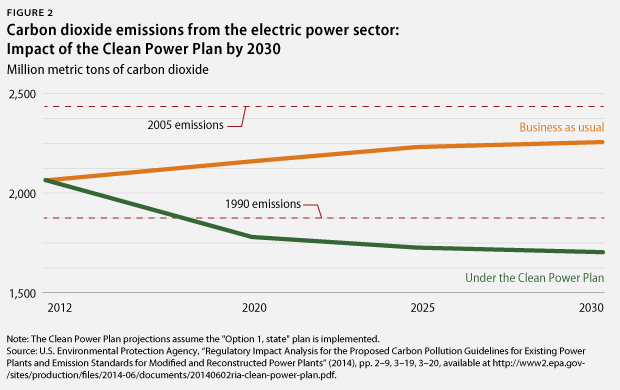

The Clean Power Plan is the key component in President Barack Obama’s plan to move the country toward a cleaner, lower-carbon energy system. The EPA estimates that by 2030, the Clean Power Plan will cut carbon pollution from the power sector to 30 percent below 2005 emissions levels, or the equivalent of 9 percent below 1990 levels. Without the plan, the EPA estimates that by 2030, carbon pollution from the electricity sector would fall just 7 percent from 2005 levels and would remain well above 1990 levels. (see Figure 2)

The EPA is set to finalize the Clean Power Plan this summer. Numerous organizations have identified ways to strengthen the plan and to achieve even deeper pollution reductions by relying more on renewable energy and energy efficiency. At the same time, opponents have been calling on the EPA to weaken the plan’s state carbon-pollution reduction targets and to extend the timeline for compliance.

Delay is not compatible with the urgency needed to prevent runaway climate change. To be clear, the Clean Power Plan alone will not be enough to achieve the economy-wide emissions reductions required to address the scope of the climate change problem. However, it is a critical start.

Alison Cassady is Director of Domestic Energy Policy at the Center for American Progress.