Our nation’s more than 400 national parks and monuments have been protected to preserve and remember extraordinary places and moments in American history, from the peaks of Yellowstone to the welcoming torch of the Statue of Liberty.

Over the past four years, federal land management agencies have made steady progress toward what may be the most fundamental change to America’s tradition of cultural, natural, and historic preservation since President Theodore Roosevelt established the first national monument more than a century ago. Under the Obama administration, the National Park Service, or NPS; the Bureau of Land Management, or BLM; and the Forest Service are creating a system of protected lands and historic sites that more accurately documents the diversity of the places, peoples, cultures, and beliefs responsible for shaping our history and better reflects who we are as a nation.

This effort is vital to not only properly record and honor our history but also to engage more and diverse groups of Americans in our nation’s parks and monuments, especially as our country continues to undergo demographic changes. The latest demographic data show a United States that is becoming increasingly diverse. More than half of all newborns are non-white, and by 2020, half of all youth will be of color. The Census Bureau predicts that by 2043, a majority of our country’s residents will be people of color.

Making our national parks and monuments more inclusive may well become a signature legacy of the Obama administration as it prepares to celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Wilderness Act this year and the centennial of the NPS in 2016. It would be a fitting legacy for a president whose own experiences in the national parks as a boy made a powerful impression. In 2012, President Barack Obama reflected on his first trip to the continental United States:

I remember that trip giving me a sense of just how immense and how grand this country was, and how diverse it was—and watching folks digging for clams in Puget Sound, and watching ranchers, and seeing our first Americans guide me through a canyon in Arizona. And it gave you a sense of just what it is that makes America special.

Already, the president has helped ensure that future generations will have more opportunities to connect with America’s natural and cultural heritage by using his executive authority to add to the diversity of our system of national parks and monuments. For example, over the past four years, he has created new national monuments to recognize, among others, Cesar Chavez and the farmworkers movement, Colonel Charles Young and the Buffalo soldiers, and Harriet Tubman and the Underground Railroad.

Additionally, the NPS has made strides in improving its efforts to provide a more complete, inclusive, and accurate account of America’s history. Seventy percent of the national landmarks established in 2011 and 2012 “reflect and tell complex stories regarding the diversity of the American experience,” according to the NPS. The agency has also updated its interpretative programs—those that help visitors understand sites, artifacts, events, history, and other resources—to provide a more accurate and inclusive view of our history, from its focus on the role of African Americans in the Civil War to new studies of the roles of American Indians and Latinos in our history.

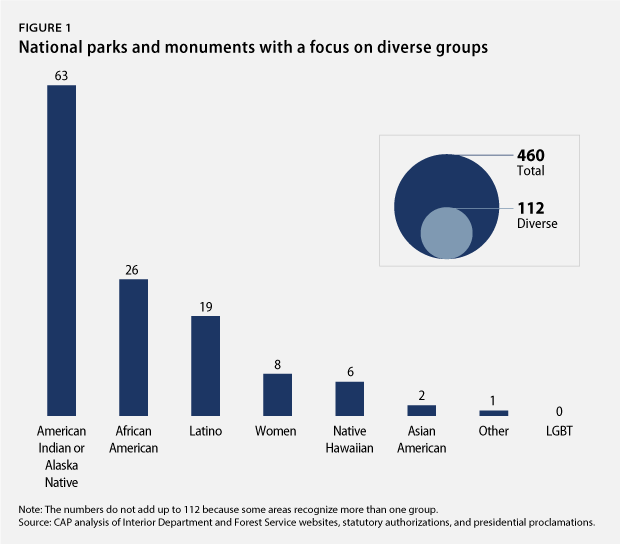

Still, much work remains to be done. In this issue brief, we discuss the importance of creating a system of national parks and monuments that better reflects the diversity of America. We also provide new data that confirm traditionally underrepresented communities in American history, including women and communities of color, remain underrepresented in America’s system of national parks and monuments. We find that of the 460 national parks and monuments, only 112—24 percent—recognize or are dedicated to diverse peoples and cultures. This is illustrated in the figure below.

To address this problem and to accelerate the administration’s work to build, by the 2016 centennial of the NPS, a system of protected lands and historic places that better reflects the contributions of all Americans—including diverse groups—to our history and culture, we offer four recommendations:

- The president should use his executive authority to protect more places, such as national monuments, that tell the entirety of America’s story.

- The administration should propose a package of conservation bills for Congress that reflects the president’s commitment to recognizing America’s diversity through the protection of land, history, and cultural sites.

- The president should appoint a panel known as the “Centennial Heritage Initiative” to provide agencies with recommendations to enhance the diversity of our nation’s national parks and monuments.

- The Obama administration should engage in expanded dialogue with American Indian and Alaska Native communities about how to create new partnerships and improve the interpretation and stewardship of cultural, historic, and natural resources.

Why it is important for our national parks and monuments to reflect our diversity

Our country’s diversity has been and will always be our biggest strength. Our story is the story of people from many backgrounds who came from all over the world to create a new experiment in freedom, equality, and democracy, where one is defined not by his or her wealth, social status, or skin color. As we develop public policies that help build a society in which all members can fully participate and prosper, it is vital that we recognize the struggles and achievements that have gotten us to where we are. What’s more, we must not provide future generations with a park experience that represents an incomplete history, fostering still more inequality and exclusion. These stories and the struggles and achievements that come with them must be reflected in our national parks—an important part of our nation’s heritage.

Making our national parks and monuments more inclusive is an important pathway to creating an inclusive America. Today, only one in five visitors to our country’s national parks is a person of color. And while Latinos are the fastest-growing group in the United States—expected to grow from 16 percent of the population in 2010 to 28 percent in 2050—only 1 in 10 national park visitors is Latino.

Even though the country has become increasingly diverse over the past several decades, according to a 2011 NPS study, the demographics of visitors to national parks and monuments have not changed significantly since they were last evaluated in 2000, largely remaining non-Hispanic white. The study, which surveyed both visitors and non-visitors, also revealed that non-visiting communities of color did not go to parks because of a lack of information about NPS parks and monuments. Additionally, both Latinos and African Americans were more likely than non-Hispanic whites to perceive NPS units as unsafe, unpleasant, or providing poor service.

Creating national parks and monuments where all communities feel welcome and empowered to visit is imperative to creating an inclusive country. Additionally, it is vital that the NPS and other agencies make efforts to connect to the new generation of Americans. Because children of color will soon be the majority of children, it is imperative to communicate our common heritage and continue to build ways for new generations to value national parks. One mechanism to do this is to make sure our national parks and monuments represent and embrace the diversity that has been, is, and will continue to be America.

It is also important to note that our society has greatly changed since our national park system was established in the early 20th century. The role of women in American society, for example, has changed dramatically as a result of women themselves. Women suffragists during this period fought for and won the right to vote, and since then, women have continued to organize for collective gains, winning equal pay and reproductive rights. Women, including those of color, have become an enormous political and economic force in our society: Businesses started by African American women grew by 258 percent from 1997 to 2013, and they are being started at six times the national average. Even with so much change and progress, however, our analysis shows that only 8 of our country’s 460 national parks and monuments are dedicated to women in American history.

This underrepresentation extends to the Latino community as well. Only 19 parks or monuments have a primary focus on Latino history, despite the fact that Latinos have always played an integral role in the American story. Hispanics of Mexican descent were already living in the southern and western regions of the North American continent centuries before the United States existed, and Latinos of all backgrounds have played a central role in the nation’s history—from exploration and settlement to the Civil War and beyond. The 2013 American Latino Theme Study, commissioned by the NPS, surveys the extent of the intellectual, political, scientific, religious, artistic, culinary, military, labor, business, and medical contributions of the Latino community to American society. They are vast. From Dr. Severo Ochoa’s discovery of the biological compound ribonucleic acid in 1959, to the 38 Latinos who have been awarded the Medal of Honor, Latino history is American history. But our parks and monuments have yet to accurately reflect their contributions.

Importantly, no national parks or monuments are dedicated to the history of the lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender, or LGBT, community. Throughout American history, members of the LGBT community have made significant contributions to our society. Bayard Rustin was an influential leader in the labor, civil rights, and gay rights movements who organized the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom—the same march at which Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his “I Have A Dream” speech. Like Rustin, countless members of the LGBT community have aided our nation’s progress, from Harvey Milk to Billie Jean King to Audre Lorde. Despite these accomplishments, however, there are no parks or monuments to commemorate the rich history of the LGBT community. As we look to the future, we must recognize the accomplishments of these leaders and what they have added to our nation.

Analysis

Any methodology for measuring whether our system of national parks and monuments adequately reflects and communicates an inclusive story of our history and culture is bound to be incomplete. This is in part because the NPS and other land management agencies conserve and transmit stories and information in many forms, from interpretive signage along a trail to digital archives and video presentations. Their work is deep and broad, and it is therefore difficult to analyze and summarize.

Yet our system of national parks and national monuments is, at a basic level, a collection of individual units designated by Congress or the president to preserve nationally significant lands, historic sites, or cultural resources. Although agencies are working to better highlight the role of traditionally underrepresented communities at a wide range of sites—including at natural wonders such as Yosemite, where the NPS has an interpretive program on the Buffalo Soldiers, and historic sites such as the Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail, where the agency interprets the history of Sacagawea and her Lemhi Shoshone tribe—a site’s primary purpose and central focus is important. In other words, it matters whether a national park unit is dedicated, as one of its primary purposes, to conserving and interpreting the history and culture of traditionally underrepresented communities. A monument dedicated to Cesar Chavez, for example, provides a place for visitors to immerse themselves in the history and achievements of the farmworkers movement in a way that no report, video, or museum panel can.

Our analysis, therefore, aims to identify how many places in our system of national parks and monuments focus mainly on the protection and interpretation of resources related to the history of underrepresented communities, including women, people of color, and the LGBT community. To conduct our analysis, we analyzed information about all 460 national park units and monuments—including national parks, national battlefields, national monuments, national historic parks, national recreation areas, national historic sites, and national scenic or historic trails—to understand the primary purposes for which each area is being protected. These areas are managed by four key federal land management agencies: the NPS, the BLM, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and the Forest Service.

We did not include National Historic Landmarks or areas listed on the National Register of Historic Places in our analysis because, while they are designated as such by the secretary of the interior, they are not managed by the federal government.

We took several aspects of federal agencies’ public presentation of information about each area into consideration, including their names, introductory information presented on website homepages, and the “History & Culture” section of the webpage for the national park units. We also considered the statutory authorizations and presidential proclamations that created the parks and monuments.

We deemed an area to be focused on traditionally underrepresented communities if the balance of publicly available information makes clear that one of the unit’s primary purposes is to protect and recognize a community’s history, culture, or contributions. For example, a unit could be focused on:

- Historic figures, such as the George Washington Carver National Monument

- Culture, such as Haleakalā National Park, which preserves the culture of Native Hawaiians

- Incidents or historically important events, such as the Trail of Tears National Historic Trail

Results

After analyzing the information we collected about the 460 national park units and monuments, we determined that 112 of them—24 percent—have a primary purpose of recognizing the historic figures, cultures, or important events of traditionally underrepresented communities.

As seen in the chart above, 63 of these 112 units have a primary focus on American Indians or Alaska Natives, 26 on African Americans, 19 on Latinos, 8 on women, 6 on Native Hawaiians, and 2 on Asian Americans. Notably, none are dedicated to the history of or historic figures in the LGBT community.

It is also worth noting that many of the sites that invoke the histories of underrepresented communities, such as the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument, have traditionally done so from the perspective of the U.S. government. It is only in recent years that the interpretation of several of these sites, including Little Bighorn, has become more inclusive and reflective of the historical record due to improvements in the NPS’s interpretive programs.

Progress under the Obama administration

The Obama administration has made good progress toward building a system of national parks and national monuments that better reflects America’s ethnic and cultural diversity.

President Obama, for example, used his authority under the 1906 Antiquities Act to establish the César E. Chávez National Monument to commemorate the important Latino leader, the United Farm Workers, and the civil rights movement. He has also protected Chimney Rock National Monument, which was home to the ancestors of modern Pueblo Indians and is a sacred site to many tribes. And the president’s first use of this same statutory authority was to protect Fort Monroe as a national monument, a location important to African American history, as it was a “safe haven” for escaped slaves during the Civil War and played a key role in the development of the legal basis for the Emancipation Proclamation.

The NPS has also tried to improve its telling of diverse stories through its National Historic Landmarks Program. As stated above, we did not include National Historic Landmarks in our analysis, but the program’s director recently told a Boston news outlet that “we are looking to preserve and protect sites associated with LGBTQ history” because only three of the nearly 2,500 national landmarks do so. The NPS reports that from 2011 to 2012, 70 percent of new national landmarks “reflect and tell complex stories regarding the diversity of the American experience.”

In addition, the Obama administration has launched new initiatives focused on women’s history and Latino history. Former Interior Secretary Ken Salazar, for example, created the American Latino Heritage Fund in 2011, which is housed at the nonprofit National Parks Foundation. The fund helps “ensure that our national parks and historic sites preserve, reflect and engage the diverse stories and communities of American Latinos throughout American History and for future generations.”

New Interior Secretary Sally Jewell is well suited to maintain the administration’s focus on expanding the diversity of America’s system of national parks and monuments. She has already launched efforts to expand the department’s youth programs and connect a new generation to the outdoors. As a member of the National Park Conservation Association’s “Second Century Commission” before her arrival at the Interior Department, Secretary Jewell also helped develop a series of forward-looking recommendations for the NPS, including “assur[ing] that all Americans are able to recognize themselves and their stories in the National Park System and in the programs of the National Park Service.”

Recommendations

To accelerate and expand the Obama administration’s efforts to make our system of national parks and monuments more inclusive and reflective of the diversity of American history and experience, we make the following four recommendations.

First, we recommend that the president use his executive authority under the Antiquities Act to create new national monuments that reflect the historic figures, cultures, and events that tell the full American story. We also urge him to combine NPS’s natural and cultural heritage missions by protecting landscapes that are of particular importance to underrepresented communities. For example, the League of United Latin American Citizens—a Latino civil rights and advocacy group—passed a resolution in September 2013 that called on the president to create the Organ Mountains-Desert Peaks National Monument in New Mexico.

Second, the administration should propose a package of bills to create new national parks and national monuments that reflects the president’s commitment to recognizing the diversity of America through the protection of land, history, and cultural sites. The past Congress was the first since World War II to not protect a single acre of land as a national park, national monument, or wilderness area, and there was no improvement last year, which was the first session of the 113th Congress.

Third, we recommend the creation of a presidentially appointed panel known as the “Centennial Heritage Initiative” that would provide the Department of the Interior and the NPS with recommendations for enhancing the diversity of our nation’s national park units, national monuments, national landmarks, conservation lands, and historic sites on the eve of the NPS’s centennial celebration in 2016. The panel would include representatives from various communities and diverse interests, including but not limited to women, communities of color, and the LGBT community. These representatives would participate in the process of national park and landmark determination and would focus especially on efforts to protect places important to communities that have not been historically well represented in these efforts. This panel should also require plans for a sustained outreach to communities of color in order to engage and create more opportunities for such communities to visit, enjoy, and make long-lasting connections with our national parks and monuments.

Finally, the administration should focus on seeking new partnerships with American Indian tribes. As noted above, 69 national parks and monuments have a primary purpose of recognizing the contributions of American Indians, Alaska Natives, and Native Hawaiians to the American story, yet few have formal partnerships with the tribes. Notably, the NPS and the Oglala Sioux tribe are working on a plan to co-manage part of South Dakota’s Badlands National Park as the nation’s first tribal national park. Additionally, the Tent Rocks national monument is co-managed by the BLM and the Cochiti Pueblo. The administration should engage in additional dialogue with American Indian nations to determine where partnerships could be created or expanded and identify areas where the interpretation and stewardship of cultural, historic, and natural resources can be improved.

With these four steps, President Obama, Secretary Jewell, Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack, and NPS Director Jon Jarvis will set the tone for the second century of our national parks and national monuments. In doing so, they will ensure that our nation’s “best idea” continues to reflect former President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s observation that, “There is nothing so American as our national parks.”

Jessica Goad is the Research and Outreach Manager for the Center for American Progress’s Public Lands Project. Matt Lee-Ashley is a Senior Fellow at the Center. Farah Ahmad is a Policy Analyst for Progress 2050 at the Center.