Introduction and summary

Last year, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) held a massive oil and gas lease sale, putting more than 300,000 acres of public lands in Nevada up for auction.1 The sale was largely in response to a request to lease the land from an anonymous individual, a routine way onshore oil and gas leasing is kicked off for the federal government.

On the day of the lease sale, however, that anonymous individual did not show up to bid—nor did anyone else, for that matter. The BLM did not sell an acre of land, not even for the minimum bid of $2.

The sale raised eyebrows. Sen. Catherine Cortez Masto (D-NV) admonished the BLM for attempting to sell off public lands with “little to no potential for drilling.”2 The head of an oil and gas industry association blamed “a bad actor” for the failed auction, hinting that the nomination was from someone trying to make the BLM or the industry look bad.3

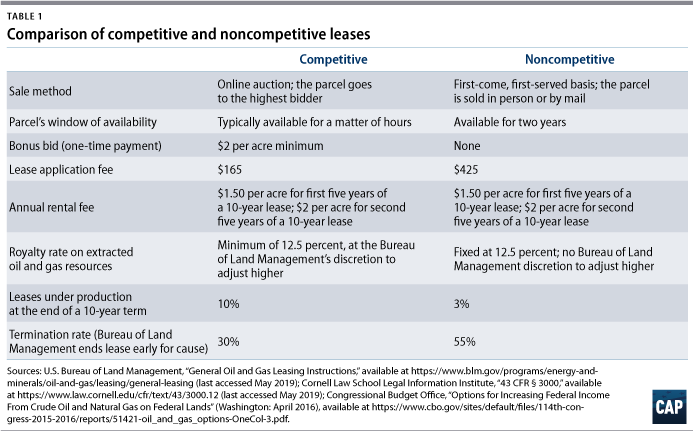

A little more than a month later, however, the BLM updated an obscure database to reflect that several parcels had been purchased after the auction by a handful of small, private oil and gas companies and speculators.4 The BLM sold the leases through its noncompetitive leasing process, whereby parcels unsold at auction are available for purchase for two years. The $2 per acre bonus bid requirement is completely waived for these parcels, so lessees simply have to pay an administrative fee, and a $1.50 per acre rental fee, making noncompetitive leasing the bargain bin of the oil and gas world.5

The newly issued leases raise more questions. Did one of the companies nominate the parcels, knowing that it was likely the company could purchase a lease for next to nothing after the failed auction? Could the companies have colluded, agreeing on the front end not to participate in the auction so they could reap the savings later? And given the area’s low oil and gas potential and the companies’ poor track records for energy development, what do they intend to do with the public lands for which they now own 10-year leases?

It’s a curious case that lays bare some of the inherent flaws in the BLM’s onshore leasing program. Oil and gas companies are able to legally stockpile public land at low prices, often without public scrutiny. This is especially true of the BLM’s noncompetitive leasing program, a scheme that few people know exists, let alone understand. However, the Center for American Progress determined that nearly one-quarter of all acres leased by the BLM in the past 10 years have been through the noncompetitive leasing process.6

In addition to comprising a surprisingly large percentage of the BLM’s leasing portfolio in terms of land, the authors found that leases sold noncompetitively generate little revenue and rarely end up in production. Instead, the public lands largely sit idle for the duration of a lease’s 10-year term—or longer, due to routine lease extensions—or the BLM terminates the lease when the lessee fails to pay rent. In other words, the BLM is wasting taxpayer resources to run an over-the-counter oil and gas leasing program that does not actually produce oil and gas.

At a minimum, these findings point to a wasteful and unnecessary leasing program that siphons away the BLM’s limited resources and shortchanges taxpayers. But the findings may also provide evidence of an underground business model in which companies buy cheap leases—not with the intent to develop oil and gas but in order to resell the parcels at profit or to pad their balance sheets with unexplored subsurface reserves. The companies or individuals that engage in this speculating and stockpiling are not in keeping with the intent of the Mineral Leasing Act, and such activity should be considered in violation of BLM regulations, which require lessees to “exercise reasonable diligence in developing and producing” oil and gas.7

This report seeks to answer some basic questions about this hidden leasing process:

- What is noncompetitive leasing, and how does the process work?

- Who is leasing public lands through this process, and what, if anything, are they doing with them?

- Who stands to benefit from this practice, and what are the impacts to American taxpayers and public lands?

The report also explores how the noncompetitive leasing process hurts taxpayers by giving away public lands at a lower rate and locking them up indefinitely so that they cannot be managed for other purposes, including conservation and outdoor recreation.

The report highlights the authors’ challenges in researching noncompetitive leasing due to the program’s lack of transparency and the BLM’s inconsistent records. Finally, the report offers recommendations to bring accountability to the BLM’s oil and gas program to ensure better stewardship of America’s public lands.

A vestige of the past: The unnecessary noncompetitive leasing program

The Bureau of Land Management manages the subsurface rights on approximately 700 million acres of federal, state, tribal, and private lands, or the equivalent of 1 out of every 3 acres in the country.8 The Mineral Leasing Act of 1920 governs the onshore oil and gas program, providing a general framework for how leases are sold, renewed, canceled, and even what royalty rates the BLM can charge companies when the leases produce oil and gas.9

For more than 60 years, the Mineral Leasing Act required that lands with “known” oil and gas deposits be leased through a competitive process, but it allowed for all other lands to be leased noncompetitively. Under this regime, 93 percent of all lands were leased noncompetitively—often through a lottery system, whereby the BLM chose a company’s winning bid at random.10

Over the years, the noncompetitive program was roundly criticized “for encouraging fraud, misleading the public, and generating insufficient revenues.”11 In one egregious example from 1983, the BLM opted to sell leases in Wyoming noncompetitively, even though there were data available revealing that the area had high oil and gas potential.12 The BLM collected $1.2 million in fees for 14 leases, and the winner immediately turned around and resold the leases closer to market value for $50 million to $100 million.13

In response to the program’s mismanagement, Congress passed a major amendment to the Mineral Leasing Act in 1987 that required the BLM to offer all lands competitively, not just those with known oil and gas reserves.14 More competition, it reasoned, would better ensure taxpayers received a fair, market-based return for private industry’s use of public lands.

A path remains, however, that allows the BLM to continue to cheaply sell vast areas of public lands on a noncompetitive basis: Any acres left unsold after a competitive auction are available for purchase the very next day on a first come, first served basis. These parcels sit on the shelf, available for purchase, for a period of two years, after which the land again could be nominated for oil and gas leasing. What’s more, the statutory minimum bid requirement of $2 per acre is waived for these parcels; a company simply must pay a nominal administrative fee and the first month’s rent of $1.50 per acre.15

In practice, this backdoor leasing process allows for any individual to walk into the BLM office and—for about the price of a pack of gum per acre—own a 10-year lease on America’s public lands.16

One can imagine scenarios in which this secondary leasing process might be justified: if lease sales are such a rare occurrence that years pass before companies can bid on parcels; if it is difficult to nominate parcels for auction in response to more favorable market conditions or technological advances that change a company’s investment calculations; or if the government needs to incentivize leasing to meet the nation’s energy needs.

But none of these scenarios are applicable. The BLM has, for the duration of its existence, run an industry-first leasing system where anyone—at any time, for free—can anonymously nominate a parcel of land and kick the leasing process into gear. Outside of the BLM’s cursory environmental review of a parcel’s nomination, there are few parameters on what public land the oil and gas industry can access or when. (see the “No money?” text box below)

The Trump administration has put this already flawed leasing process on steroids, requiring BLM state offices to include nearly all nominated parcels in statewide quarterly lease sales, slashing opportunity for public comment, and reducing internal review of nominations before they go up for auction.17

The BLM is offering for lease more acres, more often, and it is doing so at a time when the oil and gas industry is sitting on a glut of unused leases.18 In fact, there are currently nearly 26 million acres under lease to oil and gas companies—an area larger than the state of Indiana—but half of those acres are idle.19

The practice of noncompetitive leasing appears to be a vestige of the past, providing another avenue for the oil and gas industry to buy cheap leases when it already enjoys near-unfettered access to public lands and owns more leases than it knows what to do with. The cheap leases particularly benefit companies looking to inflate their value by stockpiling undeveloped reserves, as well as those that operate in the margins—buying leases on a speculative basis in order to sell them later for profit or to attract investors to unproved opportunities.

No money? No name? You, too, can nominate a parcel

BLM state offices hold oil and gas lease sales four times per year—and sometimes more frequently. What the agency offers at auction is largely determined by the private individuals and corporations who nominate public lands through what is called an expression of interest.20 To consider a nomination, the BLM simply requires a legal land description and map of the desired parcels.

The BLM does not charge any fees to submit an expression of interest. Nor does the BLM require the submitter of an expression of interest to provide a name or address. Seventy-five percent of nominations are made anonymously, and in the state of Nevada, nearly every nomination—96 percent—has been made anonymously since 2017.21 Consequently, before dedicating staff time and taxpayer resources to review an expression of interest or hold a sale, the BLM conducts no screen for whether the submitter has the intent or ability to explore or develop the oil and gas resources.

The free-for-all nature of the nomination process lends itself to abuse. An unscrupulous company or individual can easily and anonymously nominate parcels that they have no intention of bidding for in the competitive auction in order to buy it cheaply later. As-is, the system is rigged to allow for—and even encourage—speculation.

To what end?: A day in the life of a noncompetitive lease

The authors examined whether there are any notable trends in noncompetitive lease activity, as well as whether there is a discernible difference—outside of the method of sale—between leases sold competitively versus noncompetitively. To do so, CAP reviewed lease activity data in states where the Bureau of Land Management conducts leasing—other than Alaska, for which data are not readily available—and identified all noncompetitive leases issued from 2009 through 2018. The authors also reviewed the case files of 63 noncompetitive leases that the BLM Nevada State Office terminated in the past 10 years.

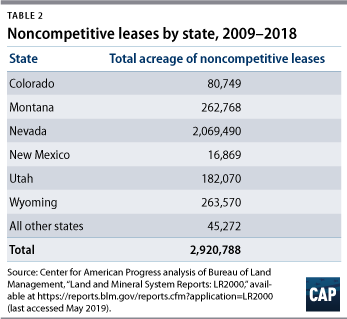

Despite Congress’ intent in 1987 to minimize the acres of public land sold noncompetitively, the data show that the BLM is still leasing a high proportion of public lands through this manner. About one-quarter of acres leased in the past 10 years were issued noncompetitively, amounting to nearly 3 million acres across the West.22

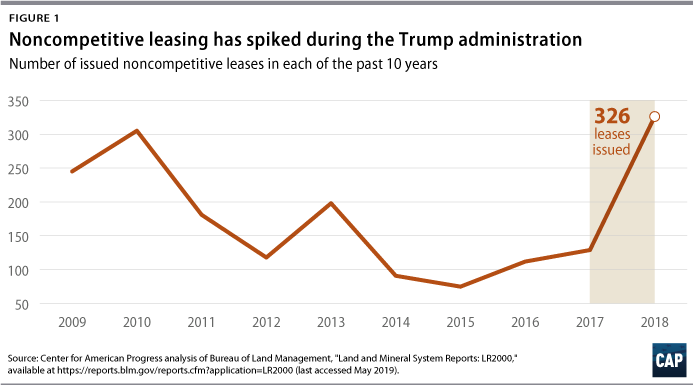

The number of acres leased noncompetitively fluctuates every year but is on the rise again under the Trump administration. From 2017 to 2018, the acres sold noncompetitively more than doubled—from approximately 141,000 acres to nearly 379,000 acres—and the number of leases issued noncompetitively was higher in 2018 than it had been in any other year over the previous decade.23 This bump is due, in part, to the fact that the Trump administration is offering more land for lease and more of it—about 2 million acres since 2017—is unsold at auction and immediately available for noncompetitive leasing.

Noncompetitive leasing happens in a number of Western states, but the practice is particularly active in Nevada, where more than 2 million acres have been sold in this manner since January 2009.24 One might expect there to be little competition for parcels in Nevada, given the state’s low mineral potential.25 By the same token, this explanation falls short of justifying why the BLM is going through the motions to effectively tie up vast amounts of public lands in Nevada and elsewhere with private companies that are unlikely to produce an economic return for taxpayers.

CAP found two hallmark characteristics of noncompetitive leases that suggest the process is particularly wasteful:

- The vast majority of noncompetitive leases sit idle. A 2016 Congressional Budget Office analysis that looked at noncompetitive leases issued from 1996 to 2003 found that only a sliver—a mere 3 percent—were developed by the end of their 10-year term.26 By comparison, leases sold competitively during that time period were developed at triple the rate, at about 10 percent.27

- Noncompetitive leases are routinely terminated by the BLM. Over the course of a 10-year lease, the BLM has the authority to terminate the agreement for a variety of reasons, including failure to pay rent. The BLM has terminated more than 1.6 million acres of the noncompetitive leases it issued since January 2009, or more than 55 percent.28 That’s nearly double the termination rate of leases sold competitively, which is closer to 30 percent.29 Many of the terminations occurred just a year or two after the BLM initially issued the lease noncompetitively.

The 63 case files of terminated leases reviewed at the Nevada BLM office provide further insight into what happens once companies buy leases noncompetitively. In every case, without exception, the BLM terminated the lease because the lessee simply stopped paying rent.30 An illustrative example: A company called American General Energy Exploration Corp. purchased 17 noncompetitive oil and gas leases from December 2014 to January 2016. Within two years, the BLM terminated every lease because the company failed to make the first rental payment owed after buying the parcel.31

The noncompetitive leasing program resembles a hamster wheel in which the BLM reviews parcel nominations; holds an auction; issues unsold oil and gas leases noncompetitively; terminates the leases when the companies fail to pay rent—and then repeats the cycle, often recycling the same parcels over again.

Some may argue that these statistics and anecdotes prove there is no harm in noncompetitive leasing, as it rarely results in any damaging development to public lands and waters. But the harm, while perhaps less tangible, is no less relevant: The BLM is spending taxpayer money on an ineffective and unnecessary program. Furthermore, Americans are losing out on a fair return for the use of their resources, and the BLM’s hands are tied from actively managing the public lands for conservation, recreation, or other beneficial purposes.

The BLM is already stretched thin, lacking adequate staff and resources to fulfill its complex multiple use mission on public lands, of which oil and gas development is a fraction. Devoting significant time to this program that, for all intents and purposes, appears to mainly benefit companies looking to pad their books or engage in speculative practices, takes away much-needed resources that the BLM could better use for public benefit elsewhere.

Gaming the system: The winners and losers in noncompetitive leasing

A review of the noncompetitive leasing program reveals a system in which the scales are tilted heavily in favor of the oil and gas industry and speculators, who risk next to nothing by exploiting the cheap leasing on public lands. The short- and long-term costs, instead, are borne by the BLM, which must devote some of its limited resources to administering the program; by the American taxpayers, who receive little in return for use of their public lands; and by the lands themselves, which are effectively off the table to be managed for other uses for which they may be better suited, such as recreation or renewable energy.

Winners

- Oil and gas industry, speculators: An entire industry may have sprung up to take advantage of cheap leases on public lands, including those available through noncompetitive leasing. A recent New York Times story contained a revealing anecdote: In 2017, a London-based company, Highlands Natural Resources, nominated tens of thousands of acres for lease in Montana, hoping that no one would bid on them during auction.32 No one did, so the company was able to scoop them up the following day for the $1.50 per acre rental fee. Highlands is now seeking investors for a “prospective” opportunity to develop the area for natural gas and helium.33

A Taxpayers for Common Sense examination of Highlands’ leasing activity shows that this approach has worked on more than one occasion. In fiscal year 2018, the company bought leasing rights on more than 113,000 acres of public land in Montana for $187,000. Because the noncompetitive leases were not subject to a bonus bid, Taxpayers for Common Sense estimates that the American public lost out on $246,000 to $3.6 million in revenue that year—the range between the $2 per acre minimum bid requirement and the average bid in Montana that year of $32 per acre.34

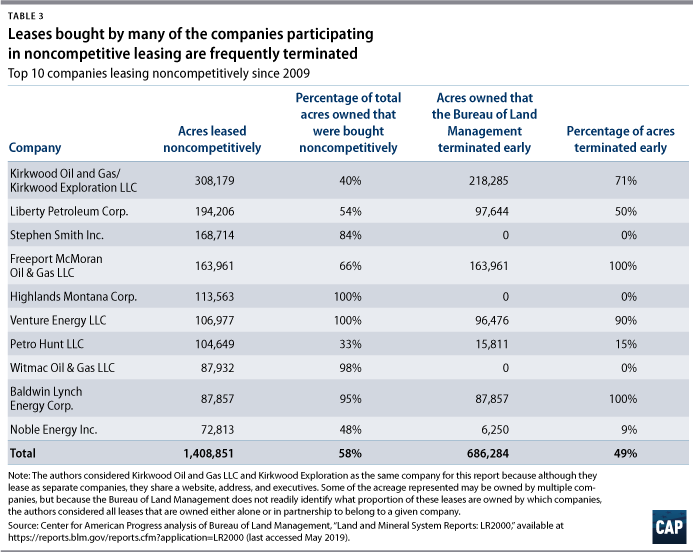

Highlands is one of more than 300 companies or individuals that purchased leases noncompetitively during the 10-year period CAP reviewed. Notably, the largest oil and gas companies—Chevron, BP, Exxon Mobil, ConocoPhillips, and Anadarko—do not appear anywhere on the list. Instead, the companies that participate in this backdoor leasing exercise are primarily small, low-profile entities, and many of them have very high rates of terminated leases and portfolios that consist primarily of noncompetitive leases.

Nearly half of the leases—accounting for more than 1.4 million acres—were purchased by just 10 companies during the 10-year window.35 Only three of the companies are publicly traded, and many of them have no identifiable websites or have websites that are outdated and skeletal. Liberty Petroleum Corp., for example, has purchased nearly 200,000 acres of public lands over the past 10 years but has not updated its website since 2013.36 For many companies, including Liberty, the addresses listed online do not match up with addresses used when buying the leases.

Finding reliable information about many of the companies was difficult for the authors and raises questions about the BLM’s ability to determine whether the actors are capable of developing the parcels—“exercising reasonable diligence,” per BLM regulations—before the agency signs over the rights to develop public lands.

In a previous report, CAP explored how cheap leases provide companies an opportunity to bolster their balance sheets superficially in order to boost their market valuation and attractiveness to shareholders and investors, thanks to a 2008 shift in U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission policy.37 Padding the books with undeveloped reserves to strengthen a company’s position in a merger or in negotiating terms of a loan may very well be a motivating factor behind some of the noncompetitive lease purchases.

Losers

- Taxpayers: Noncompetitive leasing cheats taxpayers out of receiving a fair return for the use of their public lands. Without collecting a bonus bid, and without competition to better ensure that the price reflects market value, the process effectively gives away public lands to speculators or private industry. Once the leases are sold, taxpayers also lose out on the opportunity cost of the ability to auction the acres under more favorable conditions for a higher price in the future.

CAP calculates that companies are only paying, on average, $1.74 per acre leased noncompetitively to access the land, including bonus bids, rental fees, and administrative fees. This is compared with $344 for those acres leased through the regular auction process.38 Some may shrug off this revenue gap as merely a reflection of market value: Lands with higher development potential garner competitive bidding, and some lands with lower development potential receive no bids at auction. But this explanation ignores the possibility that the same low-potential land could be offered later under stronger market conditions for a better return to taxpayers. The explanation also ignores the myriad values of public lands beyond oil and gas development potential, including their contributions to clean air, clean water, and healthy wildlife. These contributions are hard to put a price tag on, but compromising them for $1.74 per acre is tough to defend.

During the nine-year period that CAP examined, the authors estimate that the BLM collected only $4 million in leasing revenue from noncompetitive lease sales, amounting to just one-tenth of 1 percent of its total leasing revenue.39 In other words, the noncompetitive leasing revenue alone does not appear to validate the program’s existence.

- The BLM: The BLM has the largest portfolio but the smallest budget of all the land management agencies in the federal government; it should invest its limited resources in programs to benefit the American public, not in wasteful ones where the only clear beneficiary is the oil and gas industry. From reviewing parcel nominations that do not receive a single bid to terminating the leases when the lessee fails to pay rent, administering the noncompetitive leasing program spreads thin an already stretched agency. Quantifying how much money is wasted on this program is difficult. The noncompetitive leasing program is not a specific budget line item, for example. Moreover, according to the Government Accountability Office, the Department of the Interior does not effectively track the costs of environmental reviews in agency decision-making.40 An accurate accounting of BLM staff time spent processing expressions of interest, auctions, and terminations would be nearly impossible to gather without a specific directive to the agency to track this work. Lack of data notwithstanding, it is hard to justify directing any of the BLM’s scarce time and resources to administer an unnecessary program, particularly given the paltry returns in terms of revenue or oil and gas.

- Public land users: Competitive and noncompetitive leases alike afford a lessee 10 years to develop the public land for oil and gas. Frequently, lessees seek extensions from the BLM, called suspensions, which can stop that clock, sometimes for decades.41 If a parcel is in production, the lease can also last for decades. Illustratively, in 2013, about half of royalty income from onshore oil and gas came from parcels that were leased more than 50 years earlier.42 When an acre is under lease, the American public effectively loses some measure of control over the land that it owns, and the BLM cannot actively manage it for other valuable uses, including renewable energy, outdoor recreation, or conservation. The rinse-and-repeat cycle of noncompetitive leasing can stall important planning and management efforts on public lands across the West.

Across the West: What the BLM is leasing for next to nothing

Noncompetitively leased parcels dot the West, including in areas where energy development is in direct conflict with natural, cultural, or wildlife resources. Some recent examples include:

Wyoming: After a “lukewarm” competitive oil and gas lease sale in September 2018, the BLM sold eight parcels noncompetitively—more than 16,000 acres—found in the Red Desert-to-Hoback migration corridor for mule deer.43 Liberty Petroleum Corp. and Kirkwood Oil and Gas snatched up the leases for $1.50 per acre in rent, far below the statewide average bonus bid of $202 per acre.44 Studies have shown that should the leases be developed, the drilling activity stands to disrupt the large mule deer population that travels the corridor.45

Arizona: In 2018, the BLM noncompetitively leased more than 1,000 acres at the doorstep of Petrified Forest National Park to Rare Earth Exploration LLC. Local officials have expressed concerns that development in the area could threaten healthy water sources, including the tributaries to the Colorado River.46

Utah: Precisely one day after the BLM unsuccessfully offered 15 parcels at auction in 2017, Liberty Petroleum purchased three of the leases, or approximately 5,000 acres, for the $1.50 per acre rental fee. The leases are near the Molen Reef area, a region known as a “treasure trove of ancient rock art” and cultural treasures.47

Recommendations to end the noncompetitive leasing program and to minimize waste and abuse

There is a simple solution to the endemic problems in the Bureau of Land Management’s noncompetitive oil and gas program: eliminate it altogether. The costs to taxpayers and the agency far outweigh any benefits that come from providing the oil and gas industry around-the-clock, cheap access to America’s public lands. Given the abysmally low amount of revenue and development on noncompetitive leases, as well as the built-in incentive for speculators to game the system, abolishing noncompetitive leasing is the simplest, best, and most cost-effective action for Congress to take.

Ending noncompetitive leasing is not a radical recommendation. A comprehensive oil and gas reform bill introduced in previous sessions of Congress suggests taking the same action.48 The authors of this report expect that eliminating the backdoor leasing process would have a negligible impact on energy production or on the oil and gas industry itself, given the industry would still have the ability to regularly nominate and bid on parcels with a next-to-nothing minimum bid of $2.

Short of eliminating noncompetitive leasing altogether, there are several reforms the BLM or Congress could pursue that would bring much needed transparency and accountability to the entire onshore oil and gas program—noncompetitive and competitive leasing programs alike.

Improve data collection and transparency

Collecting more reliable and fulsome data, and making it publicly available, would help policymakers ensure the BLM’s oil and gas program is best serving the American public and public lands. First, the BLM should track the costs of administering a lease—from an expression of interest submission through the point of sale and beyond. The approximate staff time and resources needed to conduct the analyses and perform due diligence related to an oil and gas lease should be made public to understand the true costs of the program.

Second, the BLM should move quickly to replace LR2000 with a modern, user-friendly database. It should also standardize its guidance to state offices to ensure reliable data collection regarding oil and gas leasing activity.

Third, the BLM should release a quarterly report on noncompetitive oil and gas leasing with details including where and when parcels were leased and by whom.

Roadblocks to understanding the BLM’s noncompetitive leasing program

The BLM does not make it easy to get a full picture of the noncompetitive leasing program. Unlike leases sold through competitive auctions where the agency posts lease sale- or quarterly-specific statistics, the BLM does not provide regular updates on what is being leased noncompetitively. There is no annual report or one-stop-shop where one can gain an understanding of the practice’s scope and scale. The program’s opacity adds an unnecessary roadblock for the public, watchdogs, or Congress to ensure that the BLM is fairly administering the program.

The main way to understand oil and gas leasing activity on public lands is a cranky, outdated database housed on the BLM website called the Legacy Rehost System 2000—or LR2000, for short. The database is notoriously difficult to use—even with the BLM’s 22-page tutorial—whether to find specific information or to manipulate data for analytical purposes.49

The database also has serious content shortcomings. It does not, for example, include any data about lease sales in Alaska. LR2000 does not reliably track the reasons for lease suspensions, which is helpful information in understanding the life of a particular lease or larger leasing trends.50

When it comes to noncompetitive leases in particular, there are significant barriers to information. The only way to identify newly issued noncompetitive leases is to manually query them in LR2000, but the system sometimes takes weeks to reflect lease sales. There are coding inconsistencies that result in incomplete results unless one knows the various BLM state offices’ data entry idiosyncrasies. In short, the LR2000 is a wholly inadequate public information tool.

Encouragingly, in a recent Government Accountability Office report that recommended the BLM better standardize data collection, the BLM says it intends to “significantly update or replace LR2000 but has not set a definitive date for doing so.”51 This will be a major endeavor, so the Interior Department and Congress must make funding for the database upgrade a priority.

End anonymous nominations

Anonymous nominations should be banned across the oil and gas leasing program. Short of that, anonymously nominated parcels should not be available for noncompetitive leasing. This would shine light on companies that exploit the system by nominating a parcel, sitting out the auction, and then buying the lease later for a fraction of the cost.

Assess fees

The BLM should assess fees to recoup costs of running the program. This could be a meaningful filing fee for an expression of interest, instead of allowing anyone to nominate a parcel for free. The BLM could also consider imposing a per-acre fee on noncompetitive leases, similar to the bonus bid structure for competitive leases. These administrative fees would help deter casual speculators and shift some of the costs of administering lease sales to the oil and gas industry, instead of taxpayers.

Implement a bidder prequalification requirement and punish bad actors

Companies that are repeated bad actors should be held accountable. Under the current system, companies that routinely fail to pay rent are welcome to lease additional public lands. The BLM should implement a requirement that in order to lease more public land, a company must comply with the terms of its existing leases, including rental payments. There could also be a penalty box for companies that consistently fail to pay rent—a BLM-mandated waiting period before the company can access public lands again. These measures would cut down on the number of acres that are held in limbo for speculative reasons.

Call for an investigation

The Government Accountability Office, then the General Accounting Office, has not done a comprehensive review of the BLM’s noncompetitive leasing program since the late 1980s, when it examined the success of the 1987 amendment to minimize leases sold noncompetitively.52 Congress should request that the Government Accountability Office conduct an analysis of noncompetitive leasing related to: impacts to taxpayers; impacts to the agency budgets and resources; evidence of companies exploiting the system; and the effect on the oil and gas industry’s and the nation’s energy portfolios if the BLM were to abolish the practice.

Conclusion

Noncompetitive leasing is an outdated, wasteful, and unnecessary program that shortchanges taxpayers and provides an avenue for companies to game the system. In 1987, Congress recognized these issues and took an important step to sharply reduce the acres of public lands issued noncompetitively. More than 30 years later, however, the practice continues to account for about one-quarter of all acres leased by the Bureau of Land Management. CAP found that the program does not contribute meaningfully to the nation’s energy portfolio; rather, it puts strain on a threadbare agency, ties up public lands that could be managed for other purposes, and incentivizes speculation and abuse. Congress should take the next step and end the BLM’s noncompetitive leasing program altogether.

About the authors

Kate Kelly is the director for Public Lands at the Center for American Progress. She previously worked at the Interior Department, serving as communications director and senior adviser.

Jenny Rowland-Shea is a senior policy analyst for Public Lands at the Center. Previously, she worked on climate and energy policy at the National Wildlife Federation and holds a master’s degree in geography from The George Washington University.

Nicole Gentile is the deputy director for Public Lands at the Center. Gentile previously worked at The Pew Charitable Trusts and Environment America and holds a master’s degree in environmental law and policy from Vermont Law School.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Chester Hawkins, Christian Rodriguez, Meghan Miller, and Will Beaudouin for their art and editorial contributions to this report.