Soon after learning she was pregnant, Cherisse walked into what looked like a doctor’s office in the hopes of receiving medical information and guidance. Instead, she was shown graphic videos of abortion procedures before being sent to another facility for an ultrasound. At the second location, she was told, inaccurately, that if she ended her pregnancy, she likely would not be able to have a child in the future. She was then sent home with a bottle, a onesie, and a rattle. Cherisse found the organization that subjected her to this because it advertised itself as being focused on abortion care.1

On March 20, the anti-choice movement will argue before the U.S. Supreme Court in National Institute of Family and Life Advocates (NIFLA) v. Becerra for the right of fake women’s health centers, such as the one Cherisse was tricked into visiting, to use the First Amendment as justification to mislead and lie.

Fake women’s health centers—sometimes referred to as crisis pregnancy centers (CPCs)—are a vital part of the anti-choice movement, supported by major national organizations and anti-choice policymakers alike, while receiving significant taxpayer funding in states across the country. Since the Supreme Court’s 2016 ruling in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt restricted the movement’s ability to shut down legitimate women’s health clinics, the movement has attempted to bolster the ability of fake centers to manipulate women and block them from accessing comprehensive care—essentially, to secure the legal right to lie to women and politicize health care.

This issue brief provides an overview of the inaccuracies that fake centers spread and their role in promoting the anti-choice movement’s agenda—to the detriment of women’s health. First, the brief highlights the centers’ targeting of historically marginalized groups, including low-income communities and communities of color. It then describes legislative responses to the centers’ misleading practices before demonstrating how the legal arguments at work in NIFLA v. Becerra are the latest example of the anti-choice movement’s willingness to disregard the lives and health of women in furtherance of its political goals.

The lies and strategies of fake women’s health centers

Fake centers2 are sophisticated organizations designed to dissuade women from seeking comprehensive reproductive health services. The vast majority use misleading tactics—such as advertising that they provide information on abortion care and using names similar to those of comprehensive health clinics3—to hide their anti-choice mission and lure those whom they call “abortion-minded women”4 through their doors in order to manipulate them further. Any “counseling” provided is an attempt to further their political agenda.

Once a woman walks into a center, staff will offer her a free pregnancy test, then bombard her with medically inaccurate claims about abortion care and birth control; force her to watch graphic anti-choice videos; and shame her for even considering not continuing her pregnancy.5 The groups take a hard-line approach: Survivors of rape are subjected to the same treatment.6

If the test indicates a woman is pregnant, the center will typically double down on its propaganda, stating that if she has an abortion, she may not be able to have children in the future7 and handing out free supplies such the ones Cherisse received or diapers8 to suggest that the woman will have financial support; in reality, though, that support rarely exists. Workers have even been documented as encouraging women to ignore domestic violence, telling them that carrying a pregnancy to term may “change” the abuser.9 Furthermore, the manipulation does not end if a woman is not pregnant. Centers have been reported to provide inaccurate information about birth control and sexually transmitted diseases as well.10

The cruelty underpinning such biased, inaccurate counseling is clear. Fake centers have little regard for women and their life experiences—only a desire to adhere strictly to their political agenda.

A focus on low-income communities and women of color

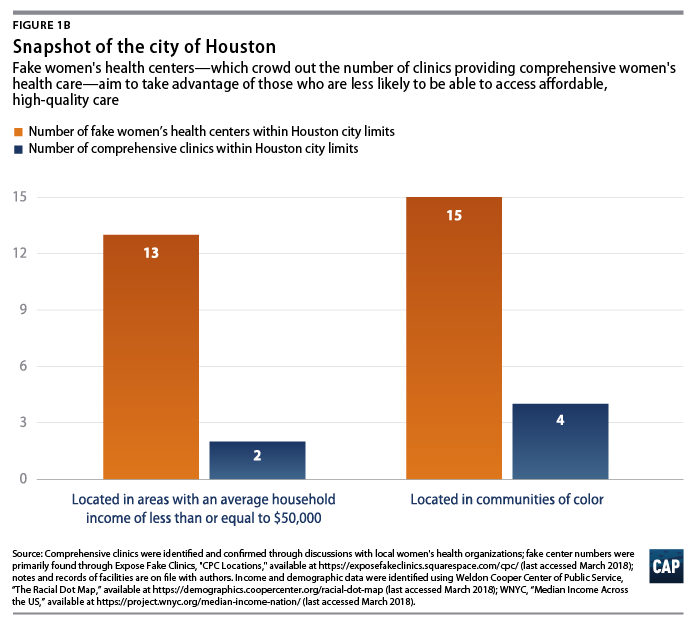

Fake women’s health centers exist in every U.S. state and number in the thousands,11 outnumbering comprehensive reproductive health care clinics that provide abortion care in every state.12 In order to strengthen their ability to lure women with promises of free services, the centers have an outsized presence—especially when compared with the number of those comprehensive clinics—in neighborhoods where many low-income people and people of color without access to affordable medical care reside.13

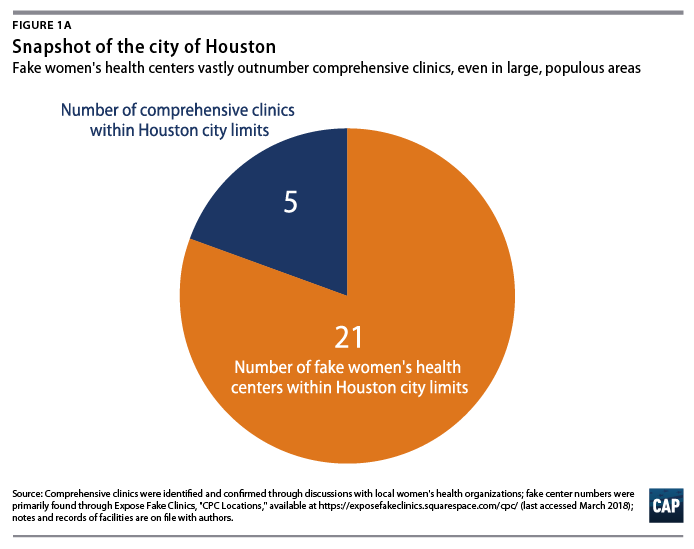

This is all the more alarming in states that provide significant taxpayer funding for fake health centers while cutting comprehensive care. Texas, for example, allocated $38.3 million in its most recent budget to its Alternatives to Abortion program, under the Texas Health and Human Services Commission, which supports fake women’s health centers.14 It is no surprise, then, that the 21 fake centers in the state’s largest city, Houston, crowd out the five comprehensive reproductive health clinics in the city; they also are overwhelmingly placed in areas with high poverty rates and in communities of color.

This exploitation of vulnerable communities is not unique to fake women’s health centers. It can be found across the country in attacks on comprehensive health care that focus on marginalized communities—women that anti-choice politicians hope will not be as sympathetic to the rest of the public.15 For example, the anti-choice movement backs efforts to decrease access to Medicaid, under which women of color are disproportionately likely to be insured, while anti-choice policymakers continue to institute dangerous federal bans denying access to abortion care for women under the program.16 The movement has also pushed for legislation that would require doctors to racially profile and discriminate against women in need of reproductive care by requiring intrusive questioning of some women of color pertaining to their reasons for choosing abortion care.17 And attempts to defund Planned Parenthood—the sole source of publicly funded contraceptive care in many low-income areas—have an outsized impact on low-income women and women of color.18

While some anti-choice advocates attempt to hide their focus on these communities, fake centers are often blatant in their efforts. Billboard campaigns, which began cropping up in the early 2000s, are a classic example of this: these organizations sponsor signs in states including New York and Florida featuring messages such as that “the most dangerous place for a black baby is in a black woman’s womb” promote their agenda and divert attention from legitimate issues that the African American community faces, such as education and wealth gaps, toward shame for women who choose to end their pregnancies.19

Fake women’s health centers’ interference in care worsens health disparities

Because of the centers’ significant presence and targeting of communities that do not have access to affordable, comprehensive health care, they often serve as the first point of contact for women seeking reproductive health services for any reason.

Unfortunately, the centers’ opposition to comprehensive reproductive health care, especially in light of their targeting of certain communities, contributes to disparities in women’s health and economic well-being nationwide.20 While overall teen pregnancy rates have fallen in recent years, significant disparities among women of color and their white counterparts remain, due in large part to disparities in access to contraception and comprehensive sexual education.21 In Massachusetts, for example, the teen pregnancy rate among young white women was just 6 percent between 2013 and 2014, while young Hispanic and African American women faced rates of 38.4 percent and 17.1 percent, respectively.22

In Wisconsin during the same time period, the white teen pregnancy rate was just under 12 percent, while their Hispanic and African American peers again faced dramatically higher rates, at 41.3 percent and 53.8 percent, respectively.23 And disparities remain even after pregnancy: Young mothers of color are significantly more likely to live in poverty compared with their white counterparts, 24 as they face inequality in access to livable wages and the corresponding impacts on education, housing, and access to health care. Through attempts to end access to birth control and abortion care, as well as to circulate misleading and medically false information about women’s health, the centers are acting to the detriment of these young women.

Regardless of whether a woman decides to continue her pregnancy, fake centers’ tactics delay her ability to speak with an honest medical professional about her medical history and needs early in the process. Cherisse, for example, ended up continuing her pregnancy even though she felt “tricked” into doing so25—meaning that her first so-called medical appointment involved false medical claims, shaming, and an ultrasound preformed without any focus on Cherisse’s own health. The danger this type of interference poses is perhaps made most clear when considering that the United States has the highest maternal mortality rate in the developed world, with African American women three to four times more likely to die in childbirth than white women.26 Access to early, high-quality care is key to preventing the pregnancy-related health complications that contribute to these tragic rates.27

Fake women’s health centers’ role in furthering the impact of historical reproductive coercion

The delays and disruptions for which fake centers are responsible can have a significant impact on women’s other health care relationships as well. Women from communities long-affected by reproductive coercion practices already have reason to distrust the medical profession, and the centers’ manipulative tactics risk worsening reproductive health care outcomes for these groups.

There is historical and deep-rooted mistrust among marginalized communities toward medical institutions that are seen as having inflicted intergenerational trauma. For example, surgical experimentation on enslaved African American women gave rise to modern gynecology, and the Eugenics Board of North Carolina forcibly sterilized more than 7,000 low-income people, people of color, and individuals with disabilities from 1929 to 1976.28 Such discrimination is still present in health outcomes today: As just one example, African American women experience pregnancy complications, HIV infections, and unplanned pregnancies at higher rates than women of other races.29

If a woman looking for unbiased reproductive health care is lured through the doors of a purposefully manipulative organization, the experience could cause her to avoid seeking out care in legitimate settings. For marginalized communities who already have a complex relationship with health care professionals, visiting a fake center can have devastating consequences not only for a pregnancy but also for a woman’s comfort accessing care for years to come. The fact that taxpayer funding supports fake women’s health centers is nothing less than a continuation of the horrifying, state-sponsored practices described above.

Legislative and legal responses to fake women’s health centers

Recognizing the dangers these organizations pose, several localities have passed laws designed to ensure that women understand what services are available in different health care settings. The types of regulations signed into law typically apply to organizations that provide pregnancy-related services, including fake women’s health centers. These laws often require an organization to make some type of disclosure in writing that it is not a medical facility or to provide visitors with information about certain services offered by the center.30 But not every law is aimed at disclosure. For example, in 2013 the Dane County Board of Supervisors in Wisconsin, passed a law preventing the county from contracting with entities that refuse to provide comprehensive, unbiased, and medically accurate reproductive health care information.31

These laws have important differences, but fake centers have challenged almost all of them in court, with varying degrees of success.32

In 2015, California passed the first statewide law in the country designed to help women make informed decisions related to their health care. A disclosure law, the Reproductive Freedom, Accountability, Comprehensive Care, and Transparency (FACT) Act has two central provisions. First, it requires covered facilities—encompassing a variety of organizations that provide pregnancy-related care, including the centers—that are not medically licensed to provide a notice stating that fact. Second, the law requires covered facilities that are medically licensed to provide a notice explaining that there are state programs that provide low-cost family planning, prenatal, and abortion care services and women can contact their local social services office to see if they qualify. Centers have great flexibility in how they provide this notice—including whether they do so through digital or hard copy, or with or without other literature the center may provide to clients.33

Represented by NIFLA, fake centers challenged the law almost immediately, arguing that the disclosures violated the First Amendment—essentially, that California was impermissibly forcing the centers to “speak” by requiring them to provide such information to women.34 The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit ruled against NIFLA, but the centers were undeterred, appealing the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court.35

NIFLA v. Becerra: A distorted focus on speech, not health

While the earlier litigation in the case referenced above involved additional constitutional issues, the Supreme Court agreed to hear arguments on only one question in NIFLA v. Becerra: whether the FACT Act’s provisions impermissibly violate the free speech clause of the First Amendment.36 At the outset, the flimsiness of the anti-choice movement’s concern with speech is clear: In a perverse twist of its claims in NIFLA v. Becerra, the movement fully supports medical professionals being directed by state officials to repeat medically false claims about reproductive health to scare women away from choosing to end a pregnancy.37

Just as the lower courts did, the Supreme Court should easily uphold the validity of the FACT Act. The law clearly passes constitutional muster under the First Amendment. While free speech protections are the bedrock of U.S. democracy, the Supreme Court has long allowed government to require simple, factual disclosures.38 The short disclosures required by the FACT Act do not force fake centers to state they support the provision of any type of care; they simply give women additional, factual information along with any information that organizations choose to provide. Indeed, the disclosures apply to organizations of a variety of viewpoints39 and are clearly justified by California’s interest in ensuring that women are aware of the full breadth of health care services available to them during an important point in their lives.

The Supreme Court has previously recognized that such information in a health care setting can “save lives” and enable people to act in “their own best interest.”40 Focusing too much on speech in this context risks ignoring the vital issue of health. Fake women’s health centers’ potential to harm does not come from their anti-choice beliefs—it comes from the damage their lies and manipulation can do to women. The right to speak should not and cannot be an excuse to do medical harm.

The anti-choice movement’s continued disregard for women

In the last major reproductive rights case to go before the Supreme Court—Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt—the anti-choice movement was deterred from using false health justifications to politicize health care41 and block women’s constitutional rights. Now, these efforts have turned to fake centers and the First Amendment in NIFLA to block those rights. The Supreme Court must recognize this attempt to distort legal rights. If it does not, it would create a legal right to use the First Amendment to harm women and deceive those who need medical care.

Fake centers’ importance in the anti-choice movement

Fake women’s health centers encapsulate anti-choice ideology: misleading women and politicizing medicine to promote the movement’s political agenda at all costs.42 Their ability to operate unchecked is essential to the movement’s success.

The professionals running these fake centers are far from well-meaning good Samaritans—they are trained in fundraising and advertising; attend annual trade conferences; and are savvy enough to lobby for laws that would help shield their nurses and doctors from malpractice claims.43

The Susan B. Anthony List, one of the most prominent anti-choice organizations in the country, lists working at a fake women’s health center as a one of the top 10 ways to get involved in its work.44 As their tactics suggest, the centers are highly organized entities. Local centers typically belong to one of three umbrella organizations: Heartbeat International; Care Net; or NIFLA, the organization litigating NIFLA v. Becerra.45 Owners of the centers benefit from these organizations’ training resources and consulting services on how best to present themselves as comprehensive health clinics so that they can mislead women looking for unbiased care and advice.

Fake centers also have powerful political backers; more than one-half of states have laws specifically designed to help the centers thrive.46 One state legislature even went so far as to pass a law, now blocked by court order, requiring women seeking abortion care to go to a fake center.47

A significant minority of fake centers have even obtained medical licenses48 in order to perform ultrasound services49 so that they can benefit from anti-choice laws that require women to undergo medically unnecessary ultrasounds before ending a pregnancy. Center leaders collaborate with anti-choice government officials to be promoted as places where women can go to receive that forced ultrasound, broadening the centers’ reach.50

The relationship between Whole Woman’s Health and NIFLA

Despite the different legal arguments in Whole Woman’s Health and NIFLA, the cases are part of the same story. They represent the essential strategy of the anti-choice movement: As one arm attempts to close comprehensive clinics, the other works to expand the power of fake women’s health centers.

In Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, the anti-choice movement claimed that burdensome regulations forcing comprehensive, legitimate clinics to shut down were designed to protect women’s health.51 The American Medical Association and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists denied this claim and opposed the restrictions as unnecessary and even dangerous.52 As with fake centers, the most significant consequences of the medically unnecessary restrictions at issue in Whole Women’s Health fell on low-income communities and women of color.53

This is reversed in NIFLA v. Becerra: To further its political agenda, the anti-choice movement is willing to ignore the legitimate health care risks the centers pose and cast about for new First Amendment protections that would contribute to deepening those risks. In contrast, on the first page of California’s brief, California Attorney General Xavier Becerra almost immediately makes clear the importance of women’s health:

…[P]atients must make timely, important, and sometimes difficult decisions affecting matters of life, health, and intimate liberty, as women must when they are pregnant. … A woman who seeks advice and care during pregnancy needs certain basic information to make informed decisions and obtain appropriate, timely medical care.54

It bears repeating that the same forces opposing California’s fact-based disclosures, support doctors being forced to tell patients demonstrably false information in other settings.55 A stronger legal interest in the right of citizens to have access to medically sound, unbiased information and care in all settings should serve as a reason to uphold the Reproductive FACT Act and invalidate harmful laws. To that end, the Supreme Court must ward off legal stunts—such as those that anti-choice forces are attempting in NIFLA v. Becerra—designed to politicize medicine at any cost. If it does not, a green light would be given to far-right extremists to erode basic health care standards in furtherance of political goals.

Conclusion

If fake centers were run by a group of people who were honest about their beliefs and wanted to provide emotional and financial support to women choosing to have a child, there would be no reason to litigate the validity of the Reproductive FACT Act. The fact that the anti-choice movement is so determined to ensure that these centers can refuse to provide even the most basic available facts on medical care shows these organizations’ true purpose.

Constitutional rights have little meaning if they are reduced to a smokescreen for a political agenda. The First Amendment was written to protect citizens from impermissible government interference—not harm their health. The Supreme Court must rule in support of the California law at issue in NIFLA v. Becerra and prevent the rollback of basic standards of medical care in service of anti-choice ideology.

Maggie Jo Buchanan is the former associate director of the Women’s Health and Rights Program at the Center for American Progress and provides expert advice to states and other entities on women’s health and economic security policy. Osub Ahmed is a policy analyst for the Women’s Initiative at the Center. Anusha Ravi is a research assistant for the Women’s Initiative at the Center.