The United States is experiencing its longest economic recovery on record, but much of the country is not reaping the benefits.1 Economic restructuring and policy decisions over the past several decades have hollowed out opportunity across the United States and left many rural communities behind. At the same time, agglomeration effects and the growth of the technology and service sectors have boosted the growth of major cities while rural areas shrink.2

Some sectors in rural America have been particularly harmed by recent changes in the economy. For example, agribusiness monopolies have put economic pressure on family farms as they struggle to survive in an age of globalization, rapid technological change, and climate change.3 Furthermore, the decline of union density has harmed workers in the manufacturing sector, a largely rural segment of the economy.4

In “Redefining Rural America,” the Center for American Progress’ inaugural installment in a series on rural communities, the authors highlighted the diversity of these regions and demanded a more inclusive narrative—and policy agenda—for the rural experience. By analyzing data across categories based on population size and proximity to metro areas, the issue brief illustrated how race and employment differ by sector across nonmetro counties.5 This issue brief expands on the authors’ previous work by examining economic trends and indicators across the rural-urban continuum at the county level. The authors’ analysis finds that some rural communities have yet to recover from the Great Recession, in part due to falling labor force participation and population loss. However, this issue brief also highlights the ways in which some communities have thrived by utilizing local assets.

In general, rural America was hit harder by the recession than were metropolitan areas and, at large, has not recovered. Specifically, this issue brief finds that:

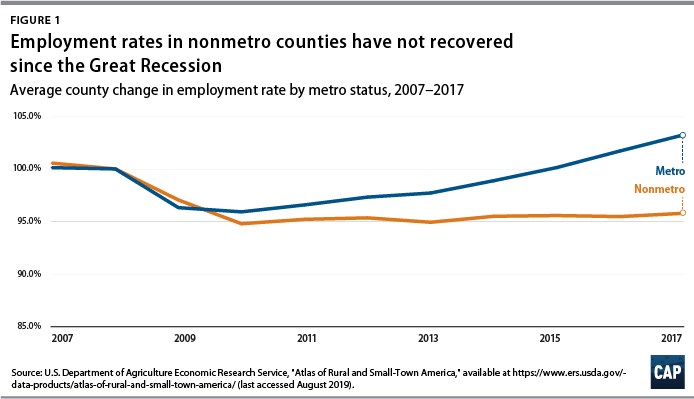

- Employment in nonmetro counties experienced a larger percent decrease than in metro counties and has yet to return to pre-2008 levels.

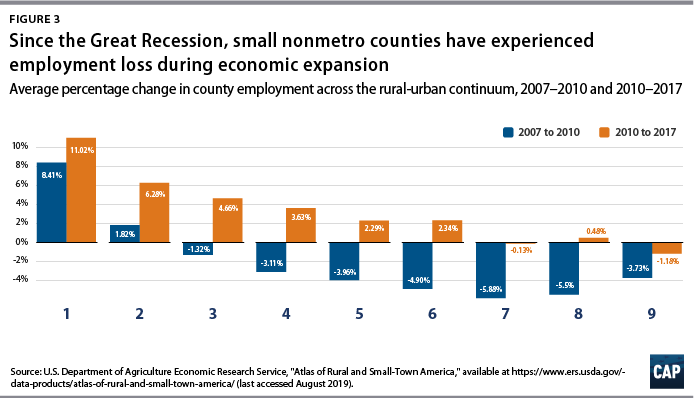

- Among metropolitan counties, only the smallest experienced a net employment decrease from 2007 to 2010; all other metro counties saw an increase in employment. Meanwhile, employment decreased significantly across all the rural categories in the rural-urban continuum. (see text box below)

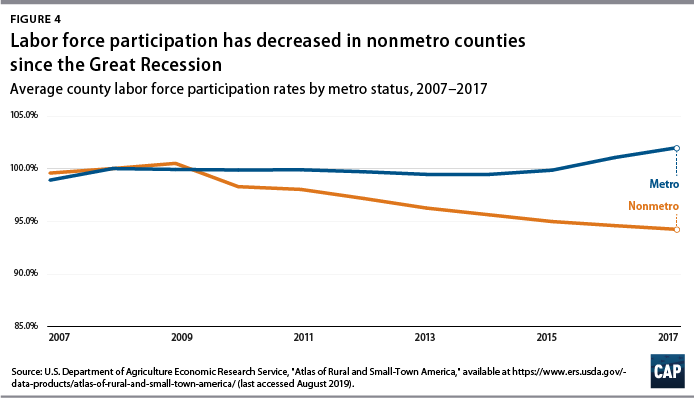

- Labor force participation in nonmetro areas has dropped by almost 6 percentage points since 2009 but has increased in most metropolitan areas.

Additionally, rural America’s overall population growth is stagnating, with some areas experiencing population loss at an alarming rate. This, in turn, can lead to economic stagnation and the loss of key services, further driving population loss in a vicious cycle.

- Overall, the most rural counties exhibited population loss both before and after the recession.

- Nonmetro population loss is not universal. Much of the Mountain West region has seen population growth, as have larger nonmetro counties.

Rural communities are not an economic liability to the country—every rural community has a unique combination of assets in which they can invest to grow and promote resilience. These assets include but are not limited to:

- Growing populations and workforces in some counties due to international immigration

- Natural resources, including amenities such as public parks as well as tradable commodities such as corn and timber

- Innovation and adaption in both the agricultural and manufacturing industries

- Community social capital resulting from close-knit communities and social infrastructure

Policymakers and pundits commonly characterize rural America as a charity case—or worse, as areas doomed to decline. While these communities face real challenges, federal investment in their intrinsic strengths can help build a brighter and more inclusive future.

The rural-urban continuum

The rural-urban continuum as defined by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Economic Research Service categorizes counties by population size and proximity to cities, providing a relational dimension to the data. Metropolitan counties are defined by the Office of Management and Budget as counties that lie within or are economically tied to metropolitan statistical areas.6 In this issue brief, the authors primarily analyze trends in rural America using the metro-nonmetro distinction and the rural-urban continuum codes, though in their discussion, they may refer to rural America in a broader sense than is captured by these limited statistical definitions. The Economic Research Service defines nine categories, or codes, along the continuum:7

Code 1: Metro county with a population of at least 1 million

Code 2: Metro county with a population of 250,000 to 1 million

Code 3: Metro county with a population of less than 250,000

Code 4: Nonmetro county with an urban population of 20,000 or more, adjacent to a metro county

Code 5: Nonmetro county with an urban population of 20,000 or more, not adjacent to a metro county

Code 6: Nonmetro county with an urban population of 2,500 to 20,000, adjacent to a metro county

Code 7: Nonmetro county with an urban population of 2,500 to 20,000, not adjacent to a metro county

Code 8: Nonmetro county with an urban population of less than 2,000, adjacent to a metro county

Code 9: Nonmetro county with an urban population of less than 2,000, not adjacent to a metro county

Rural America has not recovered from the Great Recession

Although Americans across the country felt the economic pain of the Great Recession, nonmetro counties overall were more keenly affected by the fallout from the 2008 financial crisis and have yet to recover, even as metro economies have rebounded. This rural-urban disparity is particularly apparent in employment growth and labor force participation.

Changes in employment

Total employment has surpassed 2008 levels in metro areas, but employment in nonmetro counties has improved little since the end of the recession.

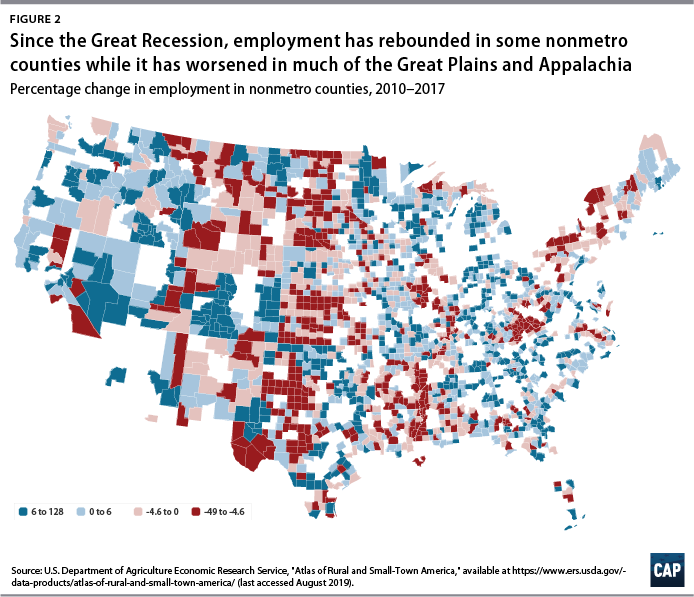

Of course, the effects of the economic pain and subsequent recovery from the recession are unevenly distributed across nonmetro counties. Much of the Great Plains continued to lose jobs even after the recession ended in 2009, as did nonmetro New York state and northern Pennsylvania. Appalachia experienced some of the worst job losses. Meanwhile, other nonmetro regions experienced employment growth comparable to that of metro areas, namely, in the Great Lakes region and the Midwest as well as in rural Nevada, Colorado, and much of the Pacific Northwest. (see Figure 2)

The authors compared counties along the rural-urban continuum to identify which communities are struggling the most. Surprisingly, even in the midst of the Great Recession, large and medium-sized metro counties saw employment growth, with large metropolitan counties experiencing an average of more than 8 percentage points of employment growth from 2007 to 2010. (see Figure 3) Meanwhile, smaller nonmetro counties experienced the most severe job losses during those years. Even after the technical end of the recession in 2009, smaller nonmetropolitan counties saw meager to negative growth on average as metro counties rebounded. While larger nonmetro counties saw average employment tick up after 2010, only code 4 nonmetro counties—counties with an urban population of 20,000 or more that are adjacent to a metro county—recouped the losses from the recession.

Decline in labor force participation

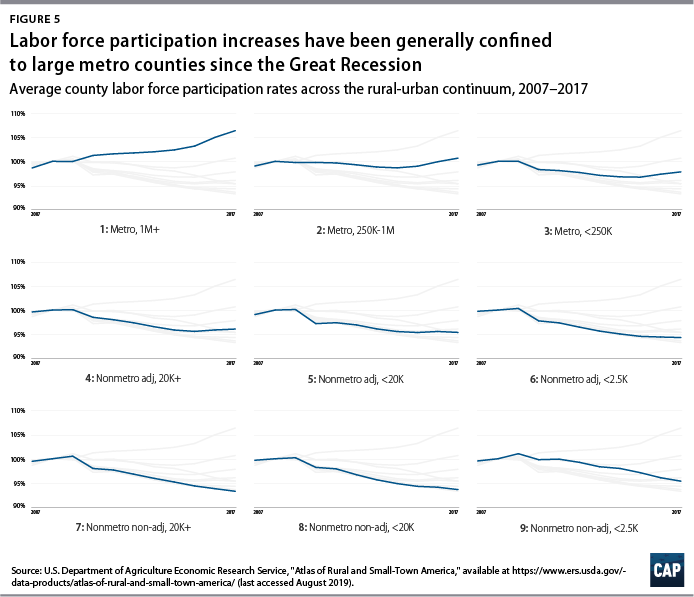

As of 2008, nonmetro counties had experienced an average decline of nearly 6 percent in labor force participation since the beginning of the recession, while metro areas maintained a similar rate throughout the recession and the recovery, from 2007 to 2017.8 This decline in labor force participation in rural areas may be due to several factors, chief among them aging demographics and disability rates that are higher than those of the nation as a whole.9 However, even among prime working-age people—who generally have lower disability rates—labor force participation has declined in rural America.10 To some extent, this widening gap in labor force participation between rural and urban areas may suggest a broader lack of opportunity, as indicated by the higher rates of long-term unemployment in rural areas.11

Much of the rise in labor force participation in metro areas is driven by high rates of migration in large metropolitan counties with populations of more than 1 million, although metro areas of all sizes saw significant recoveries, as indicated by “1: Metro, 1M+” in Figure 5. Meanwhile, the labor participation rate for larger nonmetro counties saw a modest uptick beginning in 2015, as shown by “4. Nonmetro adj, 20K+” and “5: Nonmetro adj, <20K” in Figure 5.

Despite the overall U.S. economy’s steady growth over the past decade, recovery has yet to reach many communities. Across the continuum, rural counties are suffering from declining labor force participation and stagnating employment. Moreover, rural counties that are not adjacent to metro areas, such as those in Appalachia, the Great Plains, and the rural Northeast, have yet to heal from the Great Recession.

The vicious cycle of depopulation

While the overall U.S. rural population is increasing, this growth lags far behind that of urban and suburban areas. Furthermore, many nonmetro counties are losing population at an alarming rate: More than two-thirds of nonmetro counties have lost population since 2010.12 Rural population loss to suburban and urban regions is not a new story. During the early 20th century, large numbers of African Americans moved from the rural South to northern cities to escape white supremacist violence and seek employment opportunities and better standards of living for their children.13 However, the story of net migration from rural areas since 2010 is different: Outmigration is no longer being offset by higher birth rates. Instead, natural change—defined as the number of births minus deaths—has been decreasing since the Great Recession, leading to greater population loss.

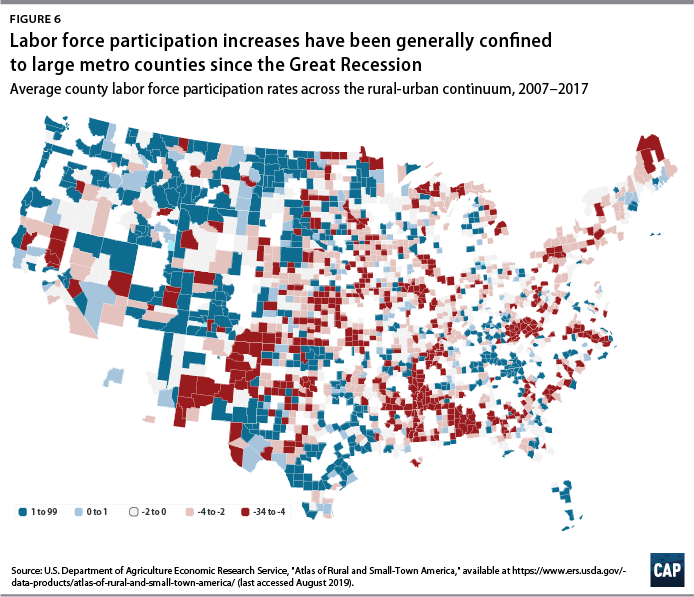

Figure 6 shows that many rural counties are experiencing population loss, especially in the Mississippi Delta region, the Great Plains, Appalachia, and the Northeast. However, Western rural counties are growing, in part due to the natural amenities they offer residents.14 Meanwhile, the energy industry may have driven some growth in isolated spots in the Dakotas, but it does not appear to have reversed population loss broadly throughout the region.15

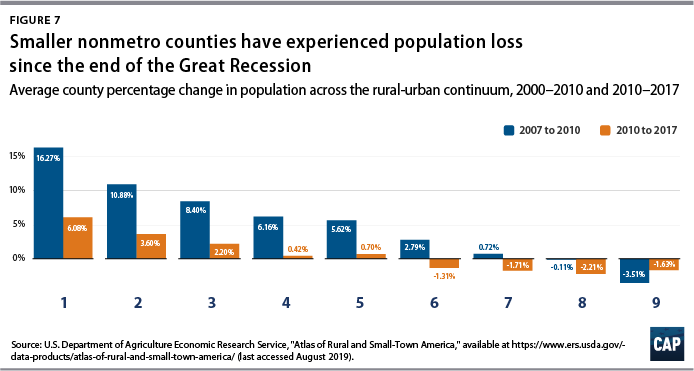

Most rural counties have experienced increased population loss since the end of the Great Recession. Figure 7 shows that during the 2000s, only the smallest nonmetro counties experienced significant population loss on average, while growth was negligible in the other small nonmetro counties. Most nonmetropolitan counties, categorized as codes 6 through 9 in the continuum, have experienced population loss on average since 2010.

Depopulation has serious implications for economic development. This is particularly true of rural depopulation, which precipitates economic decline and leaves certain regions vulnerable to an adverse chain reaction. A report by the Economic Innovation Group found that a 1 percentage-point decline in population leads to a 2 to 3 percentage-point decline in business startups.16 Rural depopulation can also result in the closures of vital services, including schools, grocery stores, and hospitals.17 As services are discontinued and economic decline accelerates, depopulation may also accelerate as young people move to cities for more opportunity, trapping communities in a negative feedback loop.

The economic inequality between urban centers and rural areas is due in part to agglomeration effects—the efficiencies and benefits achieved when similar companies are located closer together—generated by concentrating human capital and businesses.18 The easy exchange of goods and ideas feeds economic growth, attracting more businesses and workers. This, in turn, creates a positive feedback loop that causes large cities to snowball in size, greatly surpassing the growth of many smaller population centers. Rural communities, particularly those not adjacent to metro areas, lack these benefits and may struggle to retain workers who are attracted to large urban centers for their perceived economic promise.

Despite these challenges, some rural areas have been growing and even flourishing. In fact, many of the most rapidly growing rural areas have been reclassified as metro areas as a result of their success.19 For example, in 2010, 113 nonmetro counties were reclassified as metro because of the increase in their populations, while 36 metro counties were reclassified as nonmetro.20 This led to a rural population loss of 4.9 million people that year solely due to county reclassification.21 These counties demonstrate that rural areas are not doomed to decline.

Rural assets

Rural communities face unique challenges, but they also have at their disposal a combination of types of capital that they can leverage—with the help of government investment—to overcome these obstacles and flourish.22 These assets take many forms, including human capital and natural resources.23 Through public-private partnerships, community development financial institution investments, and the establishment of cooperatives, rural communities have taken their futures into their own hands and seen some encouraging progress. By studying how these communities have devised innovative solutions to local challenges, federal policymakers can better learn how to build capacity in rural areas and support their efforts through funding and programmatic support. Discussed below are a few examples of local assets and how communities can leverage them to grow and even thrive. These assets include, but are not limited to, immigration, natural resources, agriculture, manufacturing, and community social capital.

Population growth fueled by immigration

While many of the rural communities portrayed in national media are largely white and native-born, immigrants have played a large role in the recent growth of rural areas. Twenty-one percent of growing rural places nationwide owe their numbers entirely to the addition of immigrants to their communities.24 The contributions of immigrants are especially apparent in the rural West, where 99 percent of rural counties experienced growth in minority populations, including immigrants, Hispanics, and people of color.25

Immigrants have been essential to the economies of the rural communities in which they live. For example, in upstate New York, immigrants have filled a serious shortage of farmworkers on orchards and farms; and in rural areas where medical professionals are in high demand, immigrant doctors have been literal lifesavers.26 A recent CAP report highlights the importance of immigrant physicians to rural communities, where the physician-to-population ratio—13.1 per 10,000 residents—is a little more than one-third of that of metro areas.27 Beyond their economic contributions, immigrants have also contributed greatly to the vitality of their communities by putting down roots, enrolling their children in local schools, and opening their own businesses.28

Recognizing the contributions of immigrants to rural areas, the Economic Innovation Group proposed an economic development program called the “Heartland Visa” that would use place-based visas to create pathways for skilled immigrants to work and reside in left-behind communities.29 However, it is not enough to simply provide pathways for immigrants to move to rural communities; the program must also offer an infrastructure that can provide community and institutional support to welcome newcomers. Part of this approach involves the provision of services such as language instruction tailored to immigrants, as well as cultural education for existing residents to facilitate social cohesion.30

Natural resources

Some rural communities have successfully leveraged their natural amenities to revitalize their economies. Many of the rural areas experiencing economic growth have prospered, in part, due to tourism and the outdoor recreation economy. Recreation-dependent rural counties have demonstrated faster job growth compared with nonrecreation rural counties, and newcomers to these areas tend to have higher average earnings than those in other rural counties.31 While average job earnings in recreation counties are lower than in nonrecreation counties, wages in recreation counties are growing more rapidly.32 Moreover, research shows that rural counties with a higher percentage of federal lands tend to perform better on economic indicators such as per capita income and employment.33

However, these natural amenities are more vulnerable than ever, threatening the rural way of life. A recent CAP report found that every 30 seconds, the United States loses, on average, a football field’s worth of natural areas to roads, housing, and other development.34 The Trump administration has compounded this problem by opening vast amounts of previously protected lands to extractive industries.35 The loss of natural lands across the United States has created a conservation crisis with severe implications for rural economies.

The evidence is clear that sustaining nature is a superior alternative for rural communities than relying on extractive industries. To support this shift, policymakers must ensure equitable access to public lands and increase funding for outdoor recreation and conservation.36 They should also look to examples of communities that have worked to pivot from a focus on extractive industries toward conservation and clean energy. For example, Paonia, located in the North Fork Valley of Colorado, shifted from a dependence on coal mining to a more sustainable and diverse trajectory.37 The community invested in the solar energy industry, creating jobs through a nonprofit organization that trains solar technicians and consults with communities and individuals interested in harnessing solar power.38 Paonia has also taken advantage of its location to expand outdoor recreation opportunities, promote local agriculture, and make the town a tourist destination.39

Innovation and adaptation

Agriculture, an important feature of many rural economies, faces structural, economic, and environmental obstacles that are spurring a new wave of innovation among America’s farmers. The adoption of regenerative agriculture practices is helping farmers adapt to a changing climate and, in some cases, bolster their profits.40 For example, local and regional food hubs are proliferating across the country, providing farmers with alternative ways to market their products.41 In West Virginia, one nonprofit helps out-of-work coal miners supplement their income by teaching them beekeeping, strengthening their communities as well as providing valuable environmental services.42

Similarly, rural communities are learning how to adapt their manufacturing economies to an increasingly globalized market. The burgeoning market for specialty and luxury goods provides an opportunity for small and medium-sized manufacturers to differentiate their products based on quality as well as the values of their operation, which can include sustainability, community, and economic empowerment.43 By employing cooperative structures, innovating new products and business practices, and leveraging and developing existing local skillsets, some rural manufacturers are succeeding at creating high-quality jobs in their communities.44

Community social capital

One of the strengths of rural areas lies in their close-knit communities, providing an asset known as social capital. Social capital refers to social bonds, community interconnectedness, and civic engagement. While large metro areas may benefit from the multitudes of economic and social connections that yield network externalities, smaller communities with strong social infrastructure tend to be more resilient than comparable communities without it.45 For example, higher levels of community attachment and civic engagement are associated with better population retention and broader measures of social welfare.46 Strong community organizations, including churches, granges, cooperatives, sports leagues, and membership organizations such as Rotary International; third places, such as pubs and barber shops; and cultural events and traditions may offer enticing amenities to attract new residents or businesses and retain residents.47

Moreover, high levels of community social capital can greatly improve the implementation of certain programs. Government investment in community organizations and intermediaries such as public schools or extension services can improve rural life by assisting in the creation of social capital; such initiatives appear to be most successful when the government takes a facilitative role that empowers community members and centers democratic, participatory approaches.48

However, community social capital may not be accessible to everyone in a rural area. For example, LGBTQ people may not be welcome at local houses of worship and, in turn, may be excluded from other community networks or services.49 In order to mitigate this issue, communities should emphasize bridging social capital or building partnerships across differences. A study of shrinking Iowa communities found that building and investing in this source of social capital was linked to greater community resiliency.50

Conclusion

The Great Recession of 2008 and 2009 left an indelible mark on the U.S. economy. Even individuals who were able to find employment again and have seen their earnings grow remain scarred by the depths of the recession. There are many areas that have yet to recover, specifically in parts of rural America. Rural employment has yet to reach prerecession levels, and rural regions continue to experience depopulation. This depopulation contributes to lower innovation rates, which in turn depress employment growth, resulting in a vicious cycle of decline.

However, despite these challenges, rural communities present countless opportunities. In fact, there are many examples of rural American communities that have recovered and thrived by leveraging their unique strengths and resources. Policymakers should look to these success stories to provide locally relevant solutions and ensure that these areas are not left behind.

Olugbenga Ajilore is a senior economist at the Center for American Progress. Caius Z. Willingham is a research assistant for Economic Policy at the Center.

Willingham previously published under the name Zoe Willingham.