You can also read this article at Science Progress, CAP’s online science and technology journal, here.

Recently the Obama administration announced a new pilot program to create an institute for public-private collaboration and innovation in additive manufacturing in Youngstown, Ohio. The new National Additive Manufacturing Innovation Institute will serve as a platform for collaboration for more than 40 U.S. manufacturing and technology companies, nine research universities, five community colleges, and 11 nonprofit organizations across the Ohio-Pennsylvania-West Virginia “Tech Belt.”

Additive manufacturing, also known as 3D printing, is a new manufacturing technology of increasing relevance across many industries and across the globe. 3D printers work in a similar way to standard inkjet printers, except that they can use materials like plastics, carbon fiber, or titanium to print 3-dimensional objects instead of 2-dimensional documents. With prices for the technology decreasing rapidly and quality on the rise, additive manufacturing presents great opportunity for innovation in industries as diverse as aerospace, consumer goods, and medicine.

Besides showcasing a commitment to an increasingly central and cutting-edge manufacturing technology, the announcement highlights the Obama administration’s tenacity in using existing executive authority to create jobs and spur innovation despite the procrastination of a do-nothing Congress. It is also the latest in a series of the key initiatives illustrating the administration’s successful and sophisticated approach to spurring a jobs and innovation renaissance in American manufacturing industries.

In a global economy where competitiveness and job creation are increasingly driven by science, technology, innovation, and information, collaboration is key. The traditional “linear approach” to national innovation—where scientific research on the one hand and industrial production on the other are conducted and managed separately—is increasingly insufficient to cope with the increasingly interconnected nature of science, technology, and industrial production. And as these lines continue to blur, smart public investments like the new additive manufacturing institute must be similarly flexible in order to engage with an increasingly diverse network of innovation stakeholders.

“We’re not interested in building your grandfather’s research institute,” said Rebecca Blank, acting secretary of commerce, one of five federal agencies involved in launching the institute, in remarks delivered on August 16.

The approaches that worked for us in the 20th century aren’t good enough anymore. Instead, we need to build a 21st century model that reflects a strategic, global approach to competitiveness and innovation. This model has to be based on close partnerships between the academic and business world, with support from government as well. This type of collaboration is absolutely essential to ensure that Made in America remains a strong slogan well into the future.

Connecting the dots: manufacturing, innovation, and jobs

Manufacturing accounts for about 12 percent of the U.S. economy, but is responsible for 70 percent of research and development, and employs a disproportionate number of science, technology, engineering, and math, or STEM, professionals.

There is broad promise for manufacturing in America, due in part to government actions to save the automobile manufacturing industry and also in part to the innovativeness of American companies and workers. The U.S. economy has added more than 530,000 manufacturing jobs since February 2010. We haven’t seen growth that strong for this long since 1989. In addition to jobs growth, wages too have increased.

But this is only the beginning of a recovery from a decade-long manufacturing slump that has cost the U.S. economy 28 percent of its high-tech manufacturing jobs since 2002, according to a study released by the National Science Board.

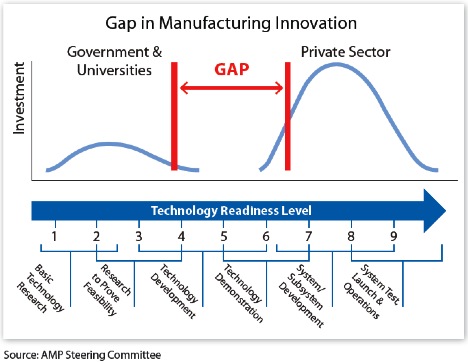

To keep the innovation-led manufacturing recovery roaring, we must continue to smooth the path for cutting-edge production-process technologies like additive manufacturing from lab research into widespread use. And to do this, we must do everything we can to build networks of innovation that connect research to practice.

As Gregory Tassey, an economist at the National Institute of Standards and Technology, writes:

The issue of co‐location of R&D and manufacturing is especially important because it means the value-added from both R&D and manufacturing will accrue to the innovating economy, at least when the technology is in its formative stages.

In other words, innovators innovate better when they interact more closely with the producers of the technology, and manufacturers manufacture better when they interact with the research into innovative methods of production. In fact, beyond researchers and manufacturers, there are at least five kinds of public- and private-sector participants involved technology innovation, each of whose success is mutually bolstered by the activities of the others, they include:

- Researchers

- Manufacturers

- Financers

- Users, or consumers

- Policymakers and regulators

No one of these innovation participants can innovate without the others. Economically meaningful technology innovation can no more be accomplished by researchers working alone in labs than by investors working alone at their computers on Wall Street. These five types of stakeholders are mutually interdependent members of innovation “networks.”

“Everyone has a role to play in making these regionally-focused institutes succeed,” said Acting Secretary Blank:

- “Governments at the local, state and federal levels can provide funds to get the institutes started. And existing resources, such as Commerce’s Manufacturing Extension Partnership which has technical experts in every state working with small companies, can provide critical on-the-ground support.

- Local universities and community colleges can make commitments to train students and workers—equipping them with the specific skill sets they need.

- Local innovation incubators and venture capital providers can help bring in entrepreneurs, mentors, and startup know-how.

- And both small and large manufacturers can contribute not only funds but also equipment, materials, and labor to get the institutes off the ground—as dozens of them have in the project we are announcing today.”

Investments in the shared infrastructure—both physical and institutional—that brings key players in a region together to collaborate and innovate are critical to maintaining our competitive position in the global knowledge economy.

What the institute does

The $70 million public-private pilot institute announced last week is the first of what the Obama administration hopes will become a network of up to 15 centers for manufacturing innovation. Based on a recommendation from the President’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, the White House budget request to Congress for fiscal year 2012 contained a plan to invest $1 billion in mandatory spending to fund the creation of these manufacturing innovation nodes.

The centers in this National Network for Manufacturing Innovation would serve three purposes, according to White House documents:

- To bridge the valley of death, by connecting the people and processes of basic research with those of product development

- To increase collaboration and participation of all innovation stakeholders, particularly small manufacturers, by providing shared access to “cutting-edge capabilities and equipment”

- To provide a platform for workforce technical skills development in fast-growing and rapidly changing sectors such as additive manufacturing

Though Congress opted not to fund the president’s request for the full network of 15 institutes, five federal agencies—the Departments of Defense, Energy, and Commerce, the National Science Foundation, and NASA—used existing authorities already granted by Congress to commit $45 million ($30 million now and $15 million in the future) to pilot the program, and prove the worth of this approach to Congress. This investment also leverages $40 million in private investment to create a hub of innovation where all of those five kinds of innovation participants—including academia, industry, nonprofits, and the government—can collaborate to innovate around additive manufacturing.

“Innovation” policy, not industrial policy

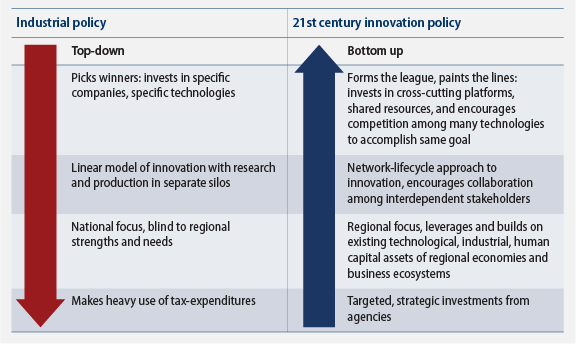

To be sure, critics will say that American manufacturers would be better off without this level of government intervention; that the initiative smacks of classic “top-down” industrial policy doomed to fail; or that government should not be in the business of “picking winners.”

But those critics are not looking very carefully at what sets this initiative—and indeed all of the Obama administration’s innovation policy initiatives—apart from the market-distorting industrial policy of past decades.

First, this effort is “bottom-up” and network driven, not top-down and bureaucracy driven. There are no government regulations, mandates, or economywide market distorting incentives involved. Instead, the five-agency program uses a competitive grant process to screen applications from self-forming consortia of public and private players all participating voluntarily and out of self-interest. Remember, the $30 million grant was made with a matching investment from the winning consortium of $40 million. The winning consortium was a network of over 70 organizations representing researchers, large and small manufacturers, educational institutions, and nonprofits who understand the value of strategic collaboration.

Next, the process was competitive and merit based. The winning consortium was chosen based on the assets it could bring to the table. This is no bridge to nowhere or industrial boondoggle; the additive manufacturing innovation institute in Youngstown will leverage and build upon the existing resources of partners in the eastern Ohio /western Pennsylvania / West Virginia region—including human capital, corporate and academic R&D capabilities, equipment, and existing industrial infrastructure. The winning consortium will also utilize capabilities and expertise from the Defense Department’s National Center for Defense Manufacturing and Machining.

Innovative cross-agency collaboration; targeted, strategic investments delivered via competitive grant programs; and leveraging the Defense Department’s extensive technological assets and investments for broader economic good are hallmarks of the Obama innovation approach. Competitive grants in particular, which have been shown to be effective at driving demand and encouraging regional collaboration, have become a signature tool of Obama administration’s innovation and economic development policies. Key examples—the Energy Regional Innovation Clusters program, the Economic Development Administration’s i6 program, and the multiagency Jobs and Innovation Accelerator—illustrate Obama administration’s sophisticated, 21st century approach to innovation policy began as early as 2009.

It is tempting to characterize these kinds of forward thinking innovation investments as “picking winners and losers.” But a better metaphor would be to say that these kinds of investments are like forming the league, setting the rules, and painting the lines on the field. Only then can the teams come together to compete and raise the level of the game. Similarly, this new additive manufacturing institute is a platform where over 40 small and large companies initially (and potentially more in the future), many of whom may be customers, clients, or competitors of one another, can share resources and guide and learn from cutting edge research.

What’s more, additive manufacturing by its nature is not a specific product in and of itself, but rather a platform technology that cuts across many industries. Variants of the technology are already being used in production in many industries, from fighter jet parts, to medical devices, to electronics, and maybe one day even synthetic human organs. Were Congress to fund the entire $1 billion National Network for Manufacturing Innovation request, we would see similar investments made in 14 other similar cross-cutting platform technologies, reducing the appearance of favoritism even further.

Critics of industrial policy are right to decry irresponsible government favoritism toward specific companies. But this pilot institute, at least from the information we currently have available in this early stage, looks like a great example of how 21st century innovation policy can be done well: by making small, strategic investments in shared capabilities; encouraging collaboration among many different companies and categories of innovation participants; and cultivating the further development of nascent regional innovation networks.

This kind of innovative thinking about the convergence of science, technology, and industry works. Large and small manufacturers and the associations that represent them are asking for it; and the numbers, with over 500,000 new manufacturing jobs added since 2010, also suggest that these kinds of investments can make a difference.

The new National Additive Manufacturing Innovation Institute will doubtlessly add momentum to the Rust Belt’s reincarnation as a 21st century Tech Belt. And with continued support from the White House and Congress, this approach to innovation policy can help drive the development of advanced technologies, create and retain more good-paying middle class jobs, and help renew the American Dream in struggling regions across the country.

Sean Pool is Managing Editor of Science Progress. Image credits, top to bottom: Flickr/dan.holton, White House Advanced Manufacturing Partnership, and American Progress.