For a more recent analysis of this issue, see “A Win in the Courts Would Harm the 10 States Suing to End DACA” by Laura Muñoz Lopez and Tom Jawetz

Last month, seven states—Alabama, Arkansas, Louisiana, Nebraska, South Carolina, Texas and West Virginia—filed a lawsuit in federal court that seeks to terminate the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program. Over the past six years, DACA has provided work permits, safety from deportation, and the ability to purse higher education to nearly 815,000 recipients who came to the United States as children.

The current lawsuit represents the second attempt by Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton (R) to end DACA. Last year, Paxton and nine other attorneys general—together with Idaho Gov. Butch Otter (R)—threatened to sue the Trump administration if it did not terminate the program by September 5, 2017. The Trump administration caved to the pressure; on that day, the administration decided to end the program, rescinding the memorandum that first created DACA and giving certain recipients just 30 days to apply for one final renewal of their protection.

In the intervening time, three different judges have ruled that the ending of DACA was likely illegal, and as of now, renewals are being processed. In the coming months, new initial applications may once more be accepted as a result of an order issued by a federal court in Washington, D.C. Texas, unhappy with these rulings, filed the current suit in a judicial district where it was predictably assigned to a handpicked judge—with a history of anti-immigrant sentiment—who could push the issue back up to the U.S. Supreme Court, or at the very least, cause even more chaos and confusion for applicants.

Despite Paxton’s repeated efforts to end DACA, appetite to end the program has dwindled. In 2014, Texas led 26 states in a lawsuit to prevent the implementation of Deferred Action for Parents of Americans and Lawful Permanent Residents (DAPA), a program that would have given parents a protected status similar to DACA. The lawsuit also challenged the expansion of DACA, which would have allowed additional undocumented youth to apply for protection. Even then, the plaintiff states made clear that they were not challenging the DACA program itself. U.S. District Judge Andrew Hanen—who presided over that suit and is now presiding over the present challenge to DACA—recognized that the DACA program itself was not affected by his ruling that blocked the expansion of DACA.

Last year, 10 of the 26 states involved in the earlier suit threatened to sue the Trump administration for not ending DACA. Within two months, however, Tennessee Attorney General Herbert Slatery (R) reversed course and withdrew his support for the lawsuit. When Texas filed suit last month, only seven of those same states joined as plaintiffs. Even Sen. John Cornyn (R-TX) has said he didn’t understand the point of the lawsuit and that “it’s not a solution.” DACA has not only been a popular and useful program for the recipients who benefited from it, but repeated polls show that a majority of Americans support DACA. In fact, nearly 87 percent of Americans and 79 percent of Republicans favor “allowing immigrants who were brought to the U.S. illegally as children” to remain in the United States.

The seven states suing to end DACA have all benefited from the presence of DACA recipients and stand to lose significantly from their lawsuit. Here are four harms these states would face if they won their case.

1. DACA recipients have made the 7 plaintiff states their home

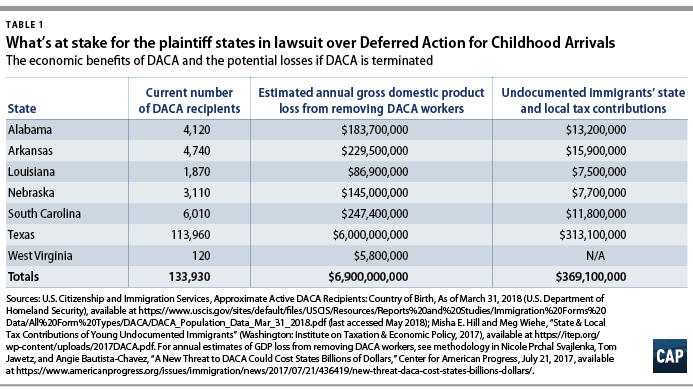

There are 134,000 DACA recipients currently living in the plaintiff states. (see Table 1) Since the beginning of DACA in 2012, research has regularly shown that the program not only works, but also improved the lives of thousands of undocumented youth and positively affected the economy.

A 2017 survey of DACA recipients by professor Tom K. Wong of the University of California, San Diego; United We Dream; the National Immigration Law Center; and the Center for American Progress showed that 91 percent of respondents are currently employed and 69 percent reported moving to a better paying job with better pay because of the program. Among DACA recipients, 5 percent started their own business—higher than the rate of starting a business among the American public. In addition, 65 percent of respondents said they purchased their first car and 16 percent purchased their first home. These purchases increase revenue and economic activity in states across the nation, including those states suing to end DACA.

2. The plaintiff states stand to lose nearly $6.9 billion in annual GDP loss

In total, the seven states that are part of the lawsuit would lose an estimated $6.9 billion in annual gross domestic product loss by kicking DACA recipients out of the labor force in the respective states. The bulk of these losses would be concentrated in Texas, which stands to lose $6 billion from its annual GDP.

3. The plaintiff states stand to lose $369 million in tax revenue

Through their employment, DACA recipients are contributors to their localities and states as wage earners and taxpayers. A 2017 state-by-state study by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy showed that the 1.3 million young undocumented immigrants receiving and immediately eligible for DACA contribute significantly to state and local taxes at an estimated $2 billion every year. The seven states suing the Trump administration stand to lose an estimated $369 million annually in state and local tax revenue they currently receive. Texas would lose the most at $313 million in revenue annually. Just as other workers in the state, DACA recipients invest part of their earned income back to the state and local government through taxes that help fund public schools, police and fire departments, and even trash pickup, among other needs, making them a large revenue contributor to the state economy.

4. DACA recipients in plaintiff states live in mixed-status families they often support

Professor Wong’s 2017 survey indicated that DACA recipients live with family members who have a wide range of immigration statuses. Seventy-three percent of respondents said they had a spouse, child, or sibling that was a U.S. citizen. An earlier version of the survey highlighted the responsibilities DACA recipients had in their families and households: Nearly 62 percent of respondents answered they helped their family pay the bills, including rent and utilities. DACA not only gives recipients financial stability, but also responsibilities that make them play a greater role in their family. Removing DACA recipients from their family would have a devastating impact on their well-being.

Conclusion

In the past couple of years, there have been repeated efforts by states to end DACA, a program that has successfully helped nearly 815,000 undocumented individuals who came to the United States as children. Recent threats make clear that until Congress passes legislation that provides permanent protection to DACA recipients and puts them on a pathway to citizenship, recipients will only continue to live their lives in limbo.

Laura Muñoz Lopez is a special assistant for Immigration Policy at the Center for American Progress.

*Author’s note: This column uses methodology from previous CAP analyses estimating the cost of ending DACA for each state, using the most recent U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services data on the number of active DACA recipients. GDP losses assume that DACA recipients lose their work permits and are removed from the workforce.