This column is an updated version of the column, “Senate Inaction on Paycheck Fairness Harms Women” by Robin Bleiweis, Jocelyn Frye, and Sarah Jane Glynn, published on July 29, 2019.

Author’s note: CAP uses “Black” and “African American” interchangeably throughout many of our products. We chose to capitalize “Black” in order to reflect that we are discussing a group of people and to be consistent with the capitalization of “African American.” The author uses Latina to refer to women who identified their ethnicity as Hispanic or Latino to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS); however, these women may be of any race. Women identified herein as “Asian” are those who identified as “Asian alone” to the BLS.

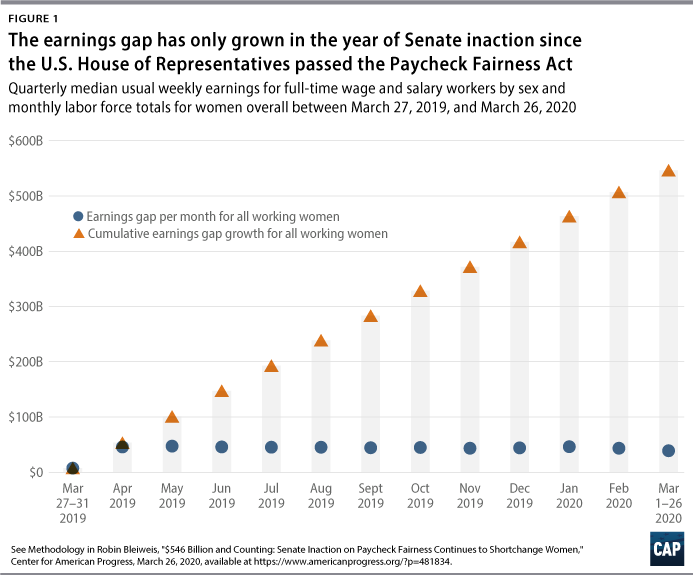

It’s been one year since the U.S. House of Representatives passed the Paycheck Fairness Act (H.R. 7)—and still the Senate has failed to take action. In the absence of meaningful action, with each passing day, women are being shortchanged and harmed by the lack of access to equal pay. The earnings gap between women and men has been a stubborn problem for decades, and it continues to erode women’s wages. Women working full time in the United States collectively earned an estimated $546.3 billion less than their male counterparts in the one year since the House passed the comprehensive equal pay legislation, according to new CAP analysis. (see Methodology and Figure 1) The same CAP analysis found that, on an individual level and in that same period, a full-time working woman earned about $9,585 less than a man on average.

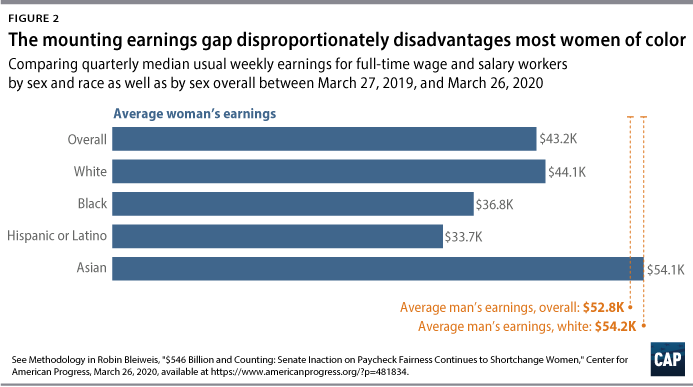

However, the numbers for women overall versus men overall only tell part of the story. When broken down by race and ethnicity, the earnings gap was larger for most women of color when compared with white men. In the same one-year analysis of full-time workers, on average, Black women earned about $17,344.36 less than white men, and Latinas earned about $20,483.36 less. (see Figure 2) Compared with white men, on average, white women earned about $10,030.93 less in that one-year period, and Asian women earned about $19.43 less. This calculation for Asian women, however, may vastly underestimate the actual gap for many women due to the wide diversity across Asian subgroups. For example, separate analysis of U.S. Census data from 2018 of median annual earnings indicates that Nepali and Hmong women working full time, year-round earned 50 cents and 61 cents, respectively, for every dollar earned by a white, non-Hispanic man in 2018, while Asian women overall earned 90 cents on the dollar. These numbers are a reminder that while the gender wage gap is often talked about in terms of cents on the dollar, the cumulative impact over time is much larger than a few cents. While these earnings gaps may not be visible on the surface, they both represent and add to economic burdens facing women and their families. Without action, these earnings gaps are not projected to close anytime soon. At the current pace of change, women overall are not estimated to reach pay parity with men overall until 2059. Even starker, Black women and Latinas are not estimated to reach pay parity with white men until 2130 and 2224, respectively.

While there are many drivers of the complex and nuanced gender wage gap, researchers have identified a significant portion that cannot be explained by quantifiable differences between men and women such as years of experience, hours worked, or time spent on caregiving responsibilities. Experts often attribute at least some of this unexplained portion—estimated by some experts to represent 38 percent or more of the gap—to discrimination and its effects. If the male-female earnings gap had been reduced by even 38 percent, women would have earned an additional $207 billion in the past year alone. That would have meant an additional $207 billion—about $3,646.14 per full-time working woman, on average—that could have helped cover the cost of groceries, child care, student loans, mortgage payments, household bills, prescription costs, emergency expenses, and more.

![NEW YORK, March 9, 2017 : Photo taken on March 9, 2017 shows the]()

Take Action: Pass the Paycheck Fairness Act

The Paycheck Fairness Act

Politicians are quick to voice support for equal pay for equal work, but empty rhetoric is not the same as concrete action. Despite the progress made by the landmark Equal Pay Act of 1963 and other civil rights legislation, the gender wage gap between women and men persists. And yet, opponents point to these existing equal pay laws—effectively ignoring the stubborn wage gap and other ongoing economic challenges that confront many working women on a daily basis—and claim that nothing else is needed. Introduced by Rep. Rosa DeLauro (D-CT) and Sen. Patty Murray (D-WA), the Paycheck Fairness Act is legislation that could begin to chip away at the persistent gender wage gap—particularly the factors that are caused or affected by discrimination. The Paycheck Fairness Act would target gender-based pay discrimination, with measures that would:

- Protect workers against retaliation for discussing pay with colleagues. Without transparency, workers are less able to identify pay disparities and potential discrimination if and where it exists.

- Prohibit the use of salary history in the interview and hiring processes. Using past salaries to determine current earnings could mean women would carry forward past discrimination with them from job to job. Not putting an end to this cyclical practice risks permanently relegating women to lower pay.

- Mandate employer collection of pay data and other employment data disaggregated by gender, race, and ethnicity. Access to pay data disaggregated by gender, race, and ethnicity is essential to identifying if and where discrimination exists.

- Close the “factor other than sex” loophole. The Equal Pay Act of 1963 has an affirmative defense framework within which employers can justify pay disparities. One is the “factor other than sex” defense, which has allowed some employers to successfully defend discriminatory pay practices that sound gender neutral on the surface. The Paycheck Fairness Act would effectively close that loophole by requiring an employer to demonstrate, in part, that the pay practice is job-related and consistent with business necessity in order to be considered legal and nondiscriminatory.

These are just a few of the major components of the comprehensive and long-overdue Paycheck Fairness Act. Additional elements include removing obstacles to class-action litigation and improving remedies for plaintiffs so that they match the remedies available under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. While the Paycheck Fairness Act will not single-handedly close the gender wage gap, it will make important strides that could bring women one step closer to securing equal pay.

Conclusion

Every day that the Senate and Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-AL) fail to pass the Paycheck Fairness Act is a day that they fail working women. Working women and their families cannot afford to wait for pay parity, especially when there is an effective, comprehensive bill that could begin to close the gender wage gap waiting for Senate action. The House passed Paycheck Fairness one year ago with a bipartisan vote—and it is long past time for the Senate to do the same.

Robin Bleiweis is a research associate for women’s economic security for the Women’s Initiative at the Center for American Progress.

Methodology

This analysis uses data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) to analyze gender earnings gaps from March 27, 2019—when the House passed the Paycheck Fairness Act—through March 26, 2020. The individual earnings gaps reported compare median usual weekly earnings (Table 2) for full-time wage and salary workers by race and gender from the first, second, third, and fourth fiscal quarters of 2019. Owing to limitations of archived BLS data, the data used for earnings of women overall and men overall (i.e., not by race) were seasonally adjusted quarterly median usual weekly earnings as reported in Table 1 of the “Usual Weekly Earnings of Wage and Salary Workers: Fourth Quarter 2019.” At the time of publication, the author did not have access to median usual weekly earnings data for the first fiscal quarter of 2020. Thus, the author projected the usual median weekly earnings for women and men overall as well as by race for the first fiscal quarter of 2020 by taking the averages of the corresponding data for each group from all four fiscal quarters of 2019. The cumulative earnings gap reported compares those same median usual weekly earnings for each fiscal quarter with monthly labor force totals for employed, full-time working women from March 2019 through February 2020. The author did not have access to BLS monthly labor force totals for March 2020 at the time of publication and projected February labor force totals for March labor force total estimates.

![]()