New data released today show that the share of Americans with incomes below the poverty line stayed flat between 2013 and 2014 at 14.8 percent. Six years into the economic recovery, poverty and economic insecurity remain far more widespread than they should be—or than they need to be. This is because policymakers have failed to make decisions—such as increasing the minimum wage and strengthening collective bargaining—that would help ensure that low- and middle-income families get their fair share of the gains from economic growth. Instead of addressing the real problem, congressional conservatives are pushing hard for policies that would make the situation far worse for families, including deep cuts to public programs that promote economic security and opportunity.

In this issue brief, we summarize notable changes between 2013 and 2014 and discuss three larger points related to the new data that are often missed in the national discussion and which provide important context for the nation’s policy decisions. First, poverty and economic insecurity are commonplace experiences, with four in five Americans experiencing poverty or related forms of economic insecurity during their working years. Second, the poverty rate remains higher than it should be because of wage stagnation and the growth of inequality, meaning that policies to boost wages and labor standards are essential tools to reduce poverty in America. And third, social insurance and assistance programs are helping Americans from all social classes and must be strengthened, not cut.

What the latest data show

The new numbers reveal that the official poverty rate stayed flat at 14.8 percent. The supplemental poverty rate—which takes into account a more comprehensive set of family expenses and income—fell from 15.8 percent in 2013 to 15.3 percent in 2014, though this decrease was not statistically significant. However, there were nearly 1 million fewer children in poverty in 2014 according to the supplemental measure—a statistically meaningful decrease.

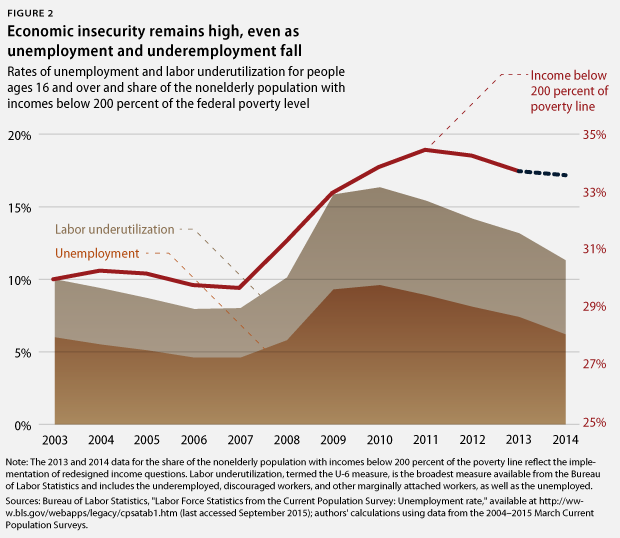

Because the federal government sets the poverty line at such a low level—only about $24,000 for a family of two parents with two children in 2014—the official poverty rate does not reflect the much larger number of Americans who are struggling on the financial brink. Surveys show that most Americans estimate that a family of four needs at least $50,000 per year to maintain an adequate but basic standard of living. Experts who study the costs of living have reached roughly the same conclusions as the public. Using this common-sense standard—equal to about twice the poverty line—about one in three Americans—33.4 percent—continued to struggle to make ends meet in 2014, roughly the same as the 33.5 percent in 2013.

Even as the jobless rate has been falling, poverty rates have been stubbornly high because the gains from the economic recovery have accrued to those at the top of the income ladder, while flat wages and underemployment have continued to plague working families. In fact, income inequality remains at or near a record level, with the top 5 percent of earners capturing 21.8 percent of total income, compared with the 12.3 percent captured by the bottom 40 percent. Census analysis shows that between 1999–the year that household income peaked—and 2014, income for the typical household declined by 7.2 percent, while income for households in the bottom 10 percent of the income distribution declined by more than twice that amount at 16.5 percent. Meanwhile, incomes for the top 10 percent increased by 2.8 percent over the same period.

In addition, a persistent gender wage gap remains, with the average woman earning only 79 cents for every $1 earned by the average man and even larger gaps for women of color. Similarly, while non-Hispanic white households saw their incomes decline by 1.7 percent in 2014, significant income disparities across race and ethnicity remain largely unchanged from the previous year. For every $1 in income received by the typical non-Hispanic white household, the typical black household received only about 59 cents, and the typical Hispanic household received about 71 cents. Racial and ethnic disparities are even more pronounced when it comes to poverty: Poverty rates stayed flat from the previous year across all racial groups, but blacks are 2.6 times more likely—and Hispanics 2.3 times more likely—to live in poverty than whites.

These stagnant poverty and income numbers in the face of economic growth focused at the top should be a wake-up call for policymakers that greater action is needed to bolster family economic security. Fortunately, with the right public policies, we can dramatically reduce poverty and inequality in America.

The larger context of the data

Poverty is a commonplace experience

Poverty and economic insecurity are commonplace experiences in America. In fact, four in five Americans experience economic insecurity during their working years, underscoring that social insurance and assistance programs offer important protections from hardship that we all need.

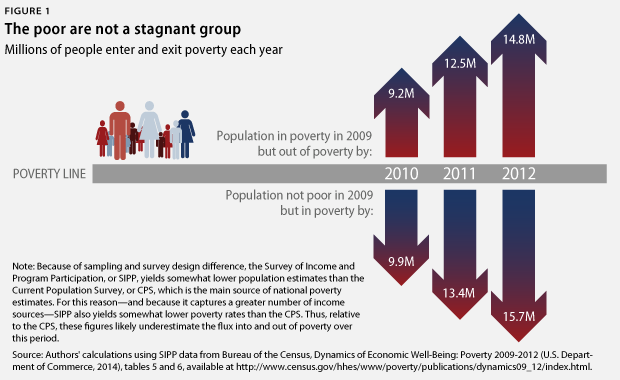

The national poverty rate represents the 46.7 million Americans with incomes below the official poverty line—roughly $24,000 per year for a family of four—last year. It is commonly assumed that the actual group of people living below the poverty line does not change much from year to year. In fact, however, movement above and below the poverty line is common: Although the percentage of people living in poverty may remain the same from year to year, many of the people who actually experience poverty each year are different.

As shown in Figure 1, the most recent Census data tracking income changes for families over time reveal that 14.8 million people who had income below the poverty line in 2009 were no longer poor in 2012. A larger number—15.7 million people—had income above the poverty line in 2009 but were poor in 2012.

In addition to annual poverty rates, the Bureau of the Census also tracks monthly poverty rates. According to this measure, a family is poor in a particular month if its income for that month falls below the annual poverty threshold divided by 12, so if a family of four had monthly income in June 2014 that fell below about $2,000, it would be counted as poor in that month. These data show that short poverty spells were quite common between 2009 and 2012, while persistent poverty was relatively uncommon. For example, nearly 35 percent of Americans saw their monthly incomes fall below the monthly poverty line in two or more months during this four-year span, while only 2.7 percent of Americans lived in poverty for all 48 months during this period.

The commonplace nature of poverty and economic insecurity is also captured in research that follows adults over the entire span of their working lives. Tracking the same adults over a roughly 41-year period from 1968 to 2009, Mark Rank, Thomas Hirschl, and Kirk Foster found that four in five adults experienced economic insecurity between the ages of 25 and 60. The researchers define economic insecurity as having annual income below 150 percent of the official poverty level, having an unemployed head of household, or receiving means-tested assistance.

Social insurance and assistance help protect children and working-age adults against a number of common risks to their economic security, including job loss, cuts to working hours or pay, illness and disability, divorce or separation, and new caregiving responsibilities. Our core public system of social insurance and assistance helps families afford basic needs such as housing, food, and transportation during tough times. Fortunately, it is there to protect all Americans—the vast majority of whom will be affected by the messy ups and downs of life at one point or another. As Congress considers deep cuts to supports such as Social Security Disability Insurance, nutrition assistance, and annually funded programs such as affordable housing and child care, policymakers would do well to remember that a much larger share of Americans than is commonly understood is at risk of hardship and has a stake in these critical programs. In other words, “the poor” are us.

Stagnant wages, eroding labor standards, and growing inequality prevent the poverty rate from falling faster

The poverty rate remains higher than it should be because of wage stagnation and the growth of inequality. Policies to boost wages and restore labor standards are essential elements of an effective strategy to reduce poverty in America.

The surest pathway out of poverty is a well-paying job. Unfortunately, even as the employment numbers have improved in the past year, the poverty rate has declined only slowly because many Americans remain stuck with flat or declining wages, reduced hours, and inadequate labor protections. This is not a new trend. Except for a brief period in the late 1990s, over the past four decades, the gains from rising profits and productivity have gone mainly to those at the top of income ladder, while average Americans have seen their wages remain flat or even decline in real terms.

Looking at just the past 10 years, the unemployment rate in 2014—6.2 percent—was roughly the same as it was about a decade earlier—6 percent in 2003. Yet a markedly higher share of Americans is experiencing economic insecurity: Just more than one-third of Americans under age 65 had incomes below 200 percent of the poverty line last year, compared with 30 percent in 2003. Figure 2 shows that while there has been a steady decline in the unemployment rate in recent years, the share of discouraged workers and underemployed workers—people working part time who would like full-time work—has remained stubbornly high following the Great Recession, as has the elevated rate of economic insecurity.

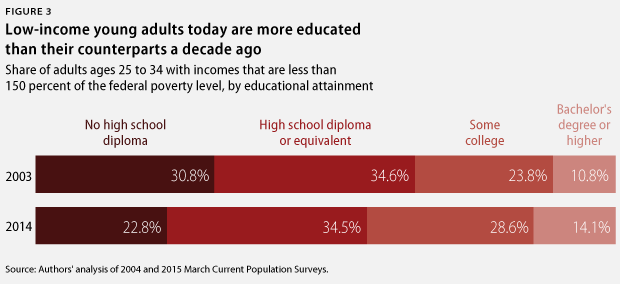

This trend does not reflect a lack of effort on the part of today’s workers. Young workers in poverty or hovering just above it—at less than 150 percent of the poverty line—are more educated than their counterparts a decade ago: A greater share has started or completed postsecondary education, and fewer than ever lack a high school diploma, as Figure 3 shows. In fact, the only educational group to experience a statistically significant increase in poverty in the past year was people with a bachelor’s degree. At the same time, today’s workers are more productive than a decade ago: Economic productivity rose by nearly 20 percent between 2003 and 2014.

Yet a lack of good jobs has made it harder for the Millennial generation to find a foothold in the middle class and has made economic stability increasingly elusive.

Several policies championed by the Obama administration would help reverse these trends. In 1975, 6 in 10 full-time salaried workers were protected by overtime, but those standards have eroded tremendously, so that today, fewer than 1 in 10 workers are protected. The president has proposed raising the pay threshold below which workers must be paid overtime from just $23,660 to about $50,440 per year. This rule would extend overtime protections to nearly 5 million more workers, raising wages for millions of families.

The Obama administration has also championed an increase in the minimum wage, which has been stuck at $7.25 per hour for six years and leaves a full-time working parent with two children below the poverty line. In fact, the inflation-adjusted value of the minimum wage is nearly one-quarter less than it was in 1968, almost half a century ago. Although conservatives in Congress have blocked progress at the federal level, workers are building momentum for national change and organizing to bring higher minimum wages to states and localities across the country.

Raising the minimum wage and enacting basic labor standards such as stronger overtime protections will be key steps toward combating growing inequality and ensuring that economic growth translates into sustained poverty reduction.

Social insurance and social assistance help mitigate poverty and inequality

Social insurance and assistance programs not only cut poverty, but they also boost long-term outcomes and mitigate economic insecurity in ways that help Americans from all social classes. Congress is currently debating cuts to these programs that would harm millions of low- and middle-income Americans and weaken critical investments in health care, education, housing, nutrition, and income security. The new Census data underscore that policymakers should not just protect but also invest in programs and policies that bolster family economic stability.

Even as historic levels of inequality have slowed the progress of poverty reduction and squeezed middle-class families’ budgets, social insurance and assistance programs have cut the poverty rate roughly in half and protected millions of low- and middle-income families from hardship.

A headline from the new Census data is the dramatic decline in the share of Americans who lack health insurance, with 8.8 million fewer uninsured Americans in 2014 than in 2013. This is mainly due to the enactment of key provisions of the Affordable Care Act in 2014, with declines that are generally the greatest in states that have expanded Medicaid. In the same vein, today’s release of the Supplemental Poverty Measure—which captures a broader range of income sources and expenses than the official poverty measure—shows that absent tax credits such as the Earned Income Tax Credit, or EITC, and the Child Tax Credit, or CTC, more than 9.8 million more Americans would have been poor in 2014. Similarly, programs such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, or SNAP; the National School Lunch Program; and housing choice vouchers and other rental assistance help millions of Americans avoid poverty. Without SNAP, for example, some 4.7 million more people would have had incomes below the poverty line in 2014.

These programs do more than just mitigate poverty and hardship in the short term. Research shows that investments such as tax credits for working-class families, nutrition assistance, and affordable housing also boost children’s long-term employment, educational, and health outcomes.

Given that the middle-class squeeze—the increased financial strain created by flat wages and rising costs—totaled approximately $10,600 for a typical two-parent, two-child family between 2000 and 2012, these investments also have been vital for millions of families struggling to make ends meet in an off-kilter economy tilted toward the wealthy few.

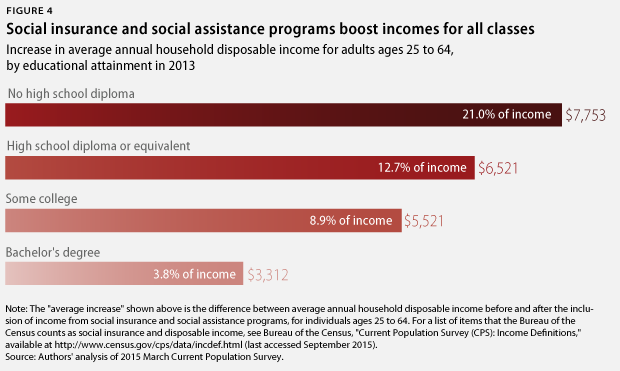

For example, Figure 4 below shows that social insurance and assistance programs lifted the average incomes of working-age people across all levels of education. Education tends to correspond closely to income. These programs are not only boosting economic security across the board but also are helping those at the bottom of the income ladder the most. In the process, these programs help mitigate the income inequality that has been exacerbated by flat wages and declining labor standards. For example, the combination of these policies—ranging from Social Security and unemployment insurance to nutrition assistance and tax credits for working-class families—not only boosted the average household income of working-age adults with high school diplomas by 12.7 percent in 2013, but it also helped those with postsecondary education by increasing average household incomes by nearly 9 percent for working-age adults with some college but no bachelor’s degree and nearly 4 percent for those with bachelor’s degrees.

Unfortunately, many of these programs are at risk of cuts. Conservatives have already indicated that they will not make a routine fix to Social Security’s funding formula without making deep cuts to critical programs for people with disabilities. Key provisions in the EITC and the CTC are set to expire in 2017, which would push 16 million Americans into poverty or deeper into poverty if Congress fails to act. The tight caps and cuts to annual funding levels caused by sequestration and the Budget Control Act of 2011 have left investments such as affordable housing and education vulnerable to deep cuts. And the House and Senate Republican budgets deeply slash SNAP and Medicaid.

Beyond just protecting what is already working, however, Congress needs to move the ball forward with a proactive agenda to cut poverty and boost the incomes of low- and middle-income families. To that end, the Center for American Progress has recommended 10 policies to cut poverty and inequality to ensure that all families have the opportunity to achieve economic security. These policies include raising the minimum wage, enacting paid family and sick leave, investing in high-quality child care and early learning, and strengthening the EITC and the CTC.

Conclusion

The new Census data underscore that far too many American families continue to struggle to make ends meet. Living standards for low- and middle-income families remain much lower than should be the case given our overall economic growth.

When it comes to cutting poverty and inequality, policy matters. Policies that reduce wage inequality and income inequality—such as raising the minimum wage and enacting the president’s overtime rule—will go a long way toward ensuring that low- and middle-income families are sharing in the nation’s economic growth. And social insurance and assistance policies are important tools to reduce poverty and inequality for all of us. They must not only be protected but also strengthened. After all, four in five Americans will experience economic insecurity during their working years. These policies are solutions for all of us, not only the 14.8 percent of Americans who were in poverty last year.

Melissa Boteach is the Vice President of the Poverty to Prosperity Program at the Center for American Progress. Shawn Fremstad is a Senior Fellow at the Center. Rachel West is a Senior Policy Analyst with the Poverty to Prosperity Program at the Center.