Introduction and summary

At the end of 2017, congressional Republicans drafted a new tax bill and rushed it to President Donald Trump for signature in just seven weeks. No congressional Democrats were permitted in the drafting sessions, and no hearings were held after the draft legislation was released.1 As a result, no other members of Congress and no members of the public whom the bill’s sweeping provisions would affect had adequate opportunity to review the proposed changes and identify potential problems—much less offer suggestions for how to improve the bill. To the surprise of no one in Washington, the final law that emerged from this secret and partisan process overwhelmingly benefits the wealthy and large corporations. The Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) and the Tax Policy Center—both nonpartisan organizations—have confirmed this fact.2

Provisions of the new tax law, informally known as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), that directly benefit the wealthy and corporations include: lowering the top individual income tax rate to 37 percent; weakening the individual alternative minimum tax, which originally was designed to ensure that the wealthy pay a minimum amount of tax; gutting the estate tax; allowing a giveaway to wealthy pass-through business owners; and slashing the statutory corporate tax rate.

As if these provisions were not generous enough, the new law creates unprecedented opportunities for tax gaming.3 As a presidential candidate, Trump repeatedly promised to eliminate the carried interest loophole, saying that wealthy hedge fund managers were “getting away with murder” and ensured that he would change that.4 U.S. House Speaker Paul Ryan (R-WI) said the tax plan was for “middle-class families” and that he and his colleagues were “getting rid of loopholes for special interests” and “making things so simple.”5 Rep. Kevin Brady (R-TX), the chair of the House Committee on Ways and Means, said the new law would provide “real relief from today’s complex, costly and unfair tax code.”6

But the law that congressional Republicans passed—and President Trump signed—fails to close many existing loopholes or eliminate special tax breaks.7 In fact, it creates new loopholes and special tax breaks,8 and it contains many mistakes and glitches.9 All of these open the door to tax gaming.

The Congressional Budget Office projected that the new tax law will drain federal revenues by $1.9 trillion over the coming decade.10 Although official revenue estimators tried to take some tax-avoidance behavior into account, history tells us that the new law could cost even more over time as well-off taxpayers find more ways to skirt the law’s provisions.11 Unfortunately, the enormous cost of the new tax law will likely threaten funding for important middle-class priorities such as education, infrastructure, and health care.

Sadly, tax gaming is highly unlikely to benefit the economy, jobs, or wages. Rather, it constitutes economically inefficient behavior pursued solely for reducing taxes. There is seldom any net new investment or productive innovation associated with the changes necessary to take advantage of tax glitches and loopholes. Ultimately, tax gaming undermines the fundamental principle that the U.S. tax system should be fair—a principle that has been seriously weakened under the new tax law.

How the new tax bill opens the door to gaming

Gaming the tax system has long been a problem in the United States.12 In fact, tax gaming has become a much greater concern in the digital age, because financial and other nonphysical or so-called intangible assets can be easily and often instantaneously transferred at a low cost to facilitate tax-avoidance maneuvers.13

But the new tax law has taken the potential for tax gaming to a new level. Since the complicated new law passed, attorneys and accountants have been working overtime to understand it and, at the same time, have been looking for tax planning workarounds for their clients. In fact, as one wealth adviser stated at a May 17 conference of the National Association of Personal Financial Advisors: “They should have just renamed the TCJA the tax professional, lawyer and financial advisor job security act of 2017.”14 Dozens of Republican staffers—many of whom helped write the law and are now leaving Capitol Hill and the Trump administration to assume lucrative positions in Washington law and accounting firms—will assist these advisers.15 The price of these trained lawyers’ and accountants’ advice is usually out of reach for all but the wealthiest individuals and largest corporations. For those privileged few, financial gains from the tax-avoidance game often far exceed the cost.

One of the law’s provisions—the deduction for pass-through business income, which the JCT estimated would reduce federal revenues by more than $400 billion over the next decade16—illustrates how the law opens the door to more gaming.

Pass-through businesses—which include sole proprietorships, partnerships, S corporations, and LLCs—do not pay the corporate income tax. Instead, the business’ income is passed through, or allocated, to the owners, shareholders, or partners, who then include their share on their personal income tax returns, where it is taxed at the normal individual tax rates that apply to wages and salary income. The new law lowered the top individual tax rate from 39.6 percent to 37 percent beginning in 2018 but gave individuals a much larger tax break on income that they receive from certain pass-through businesses. By allowing individuals to deduct 20 percent of certain pass-through business income, the maximum effective tax rate on this pass-through business income is now 29.6 percent.17

- Unequal treatment can encourage gaming. The pass-through deduction creates unequal treatment of similarly situated taxpayers, encouraging taxpayers to seek ways to recharacterize their income. For example, an employee is taxed at a maximum rate of 39.6 percent on their salary, but someone who performs the same work as an independent contractor pays a maximum effective tax rate of 29.6 percent if they qualify for the deduction. In 2012, after the Kansas state legislature passed a similar rate differential, roughly 130,000 more businesses than expected used the new tax break,18 resulting in a large revenue loss and a funding disaster for the state’s schools.19

- Complexity invites gaming. The pass-through deduction in the new tax law is exceedingly complex. Individuals who own pass-through businesses can take the deduction if they earn less than $157,500 as an individual filing separately or $315,000 as a couple filing jointly.20 Above that threshold, the deduction is disallowed and phased out completely for specified types of businesses. For the remaining businesses, the deduction is capped at an amount determined by the amount of wages the business pays to its workers or the original value of any depreciable property it owns.21 There are many special rules for and exceptions to this complicated structure.22

- Illogical rules are subject to creative interpretation. The rules of the new deduction do not make sense, and the misleading way President Trump and congressional leaders discuss the bill does not help. For instance, they claim that the provision is for small businesses. But taxpayers in the top tax bracket report more than half of pass-through business income, and taxpayers with incomes above $1 million average more than $810,000 in pass-through business income.23 In addition, the new provision creates illogical and poorly designed categories that supposedly determine who can and cannot take the deduction.24 As New York University School of Law professor Daniel Shaviro notes, there is no explanation—not even a bad one—for the deduction and the lines it draws.25 In fact, conservative economist Douglas Holtz-Eakin referred to the law as creating “haphazard lines in the sand.”26 For example, the provision references a long list of specific types of service businesses that do not qualify for the deduction and names two types—architecture and engineering firms—that do, but it does not otherwise clarify exactly what makes a business a service business. In another example, businesses that rely on the reputation of one or two people are also prohibited from taking the deduction. The lack of clarity in these rules invites taxpayers to fill in the blanks.

- Glitches allow gaming until they are fixed. Finally, this altogether new treatment of pass-through business income contains a number of mistakes or glitches—or inadvertent inconsistencies in the law.27 Legislators recently tried to fix one such glitch, only to find that the fix was flawed.28 It will take a long time for the Treasury Department, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), or Congress to address the many problems with the new deduction; meanwhile, taxpayers will have to look out for themselves and risk penalties later if they guess wrong.

Games of wealthy individuals and businesses

There are several types of tax gaming under the new law that likely will be used by wealthy individuals, including owners of pass-through businesses, since the income from these businesses is passed through to their individual tax returns.

1. Cracking: Businesses breaking apart to claim the pass-through business deduction

The lack of clarity or logic in the pass-through deduction regarding which businesses and what income qualifies has opened the door to a great deal of creative thinking about how to fit under its terms. Law professor Samuel Donaldson has referred to two games designed to take advantage of the provision’s ambiguity as cracking and packing.29

With cracking, a business operating as a nonqualifying service business may nevertheless contain components or activities that would qualify for the deduction. By cracking the business into two separate pass-through businesses, business owners can secure the deduction’s benefit for the qualifying portions of the business. An example of this approach would be a big law or lobbying firm splitting off ownership of its office building and associated furniture, gym, and restaurant into a separate pass-through business. The business income from the lawyers’ legal services would not qualify for the pass-through business income deduction, but income earned by the separate business that provides office space, furnishings, a gym, and a restaurant would likely qualify.

A key to the cracking approach is to maximize the deduction through intercompany transfers—in other words, the law firm will pay as high a fee as it reasonably can for the lease of the building, the rental of the furniture, the use of the gym, and the rental of the restaurant for law firm events. In this manner, as much nonqualified income as possible would be transferred to the lower-taxed firm. Partners in the original law firm, who own both businesses, will receive their share of income from each entity. Income from the real estate business would qualify for the deduction, while income that remains in the law firm would be taxed as ordinary income.

2. Packing: Businesses combining in order to claim the pass-through deduction

In some cases, it may make sense to pack a qualifying business into an otherwise nonqualifying business so that the combined entity is no longer primarily engaged in a business that does not qualify for the pass-through deduction. For example, as mentioned previously, the statutory language specifically states that businesses that rely on the reputation of one or two people cannot qualify for the deduction. Thus, a well-known person, such as a reality television star, could not use the deduction for their business licensing their name to others for products or services. But the reality star could pack their unrelated commercial real estate ventures, such as the buildings they own and manage, into the brand business and argue that the primary business of the combined venture is a qualifying commercial real estate business.30

3. Hedge fund managers circumventing the 3-year holding rule for carried interest

In the tax bill, President Trump failed to close the so-called carried interest loophole, as he had promised to do many times during his presidential campaign.31 Managers of hedge funds and other Wall Street private equity investment funds—wealthy individuals who then-candidate Trump said were “getting away with murder”32—are highly compensated for their services. In the loophole, these managers claim that a portion of their compensation is actually a return on investment in the fund—so-called carried interest—and thus taxable at the much lower capital gains tax rate. Even though the top individual tax rate dropped from 39.6 percent to 37 percent under the new law, it is still significantly higher than the capital gains tax rate of 23.8 percent for high-income taxpayers. Thus, managers have a strong incentive to continue using this loophole.

In a weak attempt to look tough on carried interest, legislators included a small limit on the practice: The carried interest must be held for at least three years in order to qualify for capital gains treatment. However, this restriction may be meaningless. This is because many private equity managers tend to hold onto their interests for at least that long, so they will continue to enjoy the capital gains tax rate on those shares.33

Meanwhile, hedge fund managers—who tend to hold shares for shorter periods of time—have been looking for workarounds.34 For example, many managers already have created new LLCs in Delaware—a state known for its business-friendly laws—to receive managers’ carried interest payouts. They plan to have these LLCs elect to be taxed as S corporations, since an exception from the three-year rule in the law for corporations fails to specify whether it applies only to C corporations or to S corporations as well.35 Another workaround involves converting the carried interest into reinvested capital, which is also exempt from the three-year rule, or to structure the carried interest as unrestricted performance fees.36 While the Treasury Department or Congress may strike down some of these workarounds, it seems reasonable to assume that at least one of these approaches will work for individuals seeking to game the tax law.

4. Wall Street firms and wealthy families turning themselves into C corporations

If the pass-through business deduction workarounds fail, wealthy individuals from Wall Street to Fifth Avenue may be able to shelter income from taxes by setting up their affairs as a traditional C corporation.

Wall Street C corporations

Financial services firms have been responsible for a significant share of the increased income and wealth inequality in the United States.37 They have enjoyed extraordinarily high returns on their investments—economists call these rents—while using tax-planning tricks to whittle their effective tax rates down to single digits in some cases. These firms, which are nearly all structured as pass-through entities (LLCs and S corporations), are specifically listed as not qualified for the new 20 percent pass-through business deduction, which yields an effective tax rate of 29.6 percent.38

While many financial services managers will still be able to take advantage of the carried interest loophole to achieve a 20 percent rate on a large portion of their earned income, financial firms that rely more on management fees charged to investors may not. Management fees are taxed as ordinary income when distributed to the partners. These partners need not worry, however, because the new law offers them a legal way to avoid more taxes.

Under the new tax law, partners in these firms may still avoid higher taxes by converting the partnership to a C corporation. The firm’s income would then be taxed at the new low 21 percent corporate tax rate. While distributions to the partners-now-shareholders in the form of dividends are taxed again, as are gains on shares that are sold, the maximum rate on this second layer of tax would be only 23.8 percent. Thus, the combined effective tax rate on corporate profits would be 39.8 percent—only slightly more than the 37 percent top rate on individual income, which will revert to 39.6 percent in 2026.

The C corporation structure may have further benefits. For example, the new law exempts from tax dividends that a U.S.-controlled foreign subsidiary pays to a U.S. corporation, but not dividends that the foreign subsidiary pays to an individual U.S. investor or a U.S. pass-through entity—even if the individual investor or pass-through business owns a controlling share of the foreign subsidiary. But if the individual investor or pass-through forms its own C corporation, it may then be able to avail itself of the so-called participation exemption. In this way, the dividends from the foreign corporation are paid to the newly formed U.S. corporation and thus potentially qualify for the tax-free repatriation of profits from the foreign company. Later, when the new U.S. corporation—which, again, the wealthy individual investor owns—distributes dividends to the individual, the much lower 23.8 percent tax rate on dividends applies.39

There also are a number of options for lowering or eliminating that second layer of tax when operating as a C corporation. For example, earnings can be retained in the corporation for a number of years, thus deferring the second layer of tax indefinitely—a valuable benefit. Moreover, if a partner and/or shareholder holds onto their shares in the new C corporation until they die, the shares will transfer to their heirs free of income tax. This loophole existed before the 2017 tax law was passed, but President Trump and congressional leaders failed to close it. Therefore, heirs can claim ownership of the shares at the value they have on the date of their inheritance, rather than having to pay the income tax that would have been due on the gains that occurred while their parent or the previous owner held the shares. This so-called stepped-up basis loophole is likely to become a bigger problem with renewed interest in C corporations as tax shelters.40

Even large publicly traded partnerships (PTPs) are seeing the tax benefits of the switch to C corporation status.41 There are costs to converting, and it is difficult to convert back to a pass-through entity. Yet the fact that the corporate tax provisions are permanent—while the new pass-through deduction is temporary—makes this a better tax-planning tool for some large financial services firms. Although large partnerships that convert to C corporations may hope this move ultimately will attract more passive investors in their business, the bottom line is that the change is largely a tax-avoidance move.

Wealthy family C corporations

Converting to a C corporation also offers wealthy families of all kinds an opportunity to shelter income from tax. By forming a family C corporation or converting an existing family pass-through business to a C corporation, wealthy families can take advantage of the increased gap between the top tax rate on individual income—which is now 37 percent (39.6 percent after 2025)—and the rate on corporate income, now 21 percent.

As in the 1970s, when the individual income tax rate also was much higher than the corporate income tax rate,42 wealthy lawyers, lobbyists, managers, doctors, and family business owners will now have a greater incentive to incorporate to lower their overall tax bill. They will have their substantial salaries paid directly to the corporation, then have the corporation pay themselves as small a salary as reasonable, with the remainder retained in the corporation. In this manner, a significant portion of their labor income, which otherwise would have been taxed at 37 percent (again, 39.6 percent after 2025), is converted into corporate income to be taxed at 21 percent. If the net income were immediately distributed each year as dividends to the owner-shareholders, the distributed income would be taxed at the individual level of 20 percent plus the 3.8 percent net investment income tax (NIIT), which adds up to an effective rate of 39.8 percent—roughly the same as the rate on their salary.43 But there are several additional advantages of the C corporation that likely will more than offset the slightly higher effective tax rate.

The family C corporation may be able to deduct more of its state and local taxes from the C corporation’s income, as well as fringe benefits such as health care. The new law limits the state and local tax deduction to $10,000 for individuals who itemize. Only state and local sales or property taxes above that amount can offset the individual’s pass-through business income—and only if they relate to the business. However, a C corporation faces no limit on the deductibility of state and local taxes so long as the taxes are related to the business. Also, the new law limits the ability of pass-through business owners to use excess business losses to offset other income—they can only deduct up to $250,000 as a single tax filer or $500,000 as a married couple filing jointly. However, this new limitation does not apply to C corporations.

A family C corporation can also take advantage of the previously mentioned ways for C corporation owners to avoid the second layer of tax when earnings are distributed. But they may also qualify for another loophole under Internal Revenue Code Section 1202 that provides special capital gains treatment for qualifying small businesses.44 Capital gain on qualified small business stock is excluded from the capital gains tax up to a limit of $10 million. This provision should have been repealed to close off this loophole.45

Wealthy families have traditionally used various kinds of trusts to shelter their wealth from tax—especially the estate tax—but trusts usually impose restrictions on the use of those assets. A C corporation, where workable, may afford a wealthy family much more flexibility on how they use their assets while potentially avoiding even more tax.

One caveat to the C corporation as tax shelter is that the tax code includes personal holding company rules and accumulated earnings tax rules that may limit the benefits of this approach, but tax planners are hard at work figuring out ways to get around those rules, too.46 Of course, the rules were intended to prevent tax avoidance, and there will be a lot more pressure on these anti-abuse rules now that the low corporate rate is providing such a strong incentive for families to convert to C corporation status.

To be clear, there is no benefit to the economy if a wealthy family sets up a C corporation effectively to hold its assets. Rather, this tax-gaming strategy reduces contributions of the wealthy to federal revenues—revenues that could be used to fund efforts such as infrastructure improvements, education, health care, and more.

5. Wealthy families using dynasty trusts to maximize the estate tax cut

The new tax law doubled the amount of assets that are exempt from the estate tax from more than $5 million per individual to more than $11 million per individual (and more than $22 million per couple), representing a handout exclusively for wealthy families. The provision is scheduled to expire at the end of 2025, at which point the estate tax exemption will revert to pre-2018 levels. One might think that the opportunity to use this new provision would be limited, since the beneficiary of it would have to die first—but this is not so.

A number of states, such as Alaska, Delaware, Nevada, New Hampshire, and South Dakota, allow individuals to set up long-term trusts that can provide income to successive generations of a family without incurring transfer taxes such as the estate and gift tax and the generation-skipping transfer tax, which impose taxes on transfers to grandchildren and great-grandchildren.47 These so-called dynasty trusts are irrevocable, so the assets the wealthy person puts into them are not included in the individual’s estate when they die.48 And, importantly, assets deposited in the trust take advantage of the estate and gift tax exemption in force at the time of the transfer to the trust—giving the wealthy a means of taking advantage of the much larger estate tax exemption, even if the wealthy individual does not expire before the larger exemption does.49

Over the past decade, the nation’s wealthiest families have seen their assets increase dramatically in value; thus, they have a strong incentive to move their assets into trusts and other structures that will defer tax on the gain. The dynasty trust tax dodge existed before the new law was passed—Treasury Secretary Steven Mnuchin listed one on the financial disclosure forms he filed at the time of his nomination50—but the dramatically increased estate tax exemption creates a window of opportunity to squirrel away even more wealth tax free. In other words, Secretary Mnuchin—along with anyone else who already has a dynasty trust—can now double the amount they deposit in the trust. And newly wealthy individuals will have an incentive to create a dynasty trust while the exemption is so high. If individuals deposit assets such as vacation homes or jewelry that do not throw off income but do increase in value, they will not owe tax as the value of the assets’ increases.51 Not surprisingly, wealth planners say they have seen increased interest in dynasty trusts since the law passed.52

Corporate and international games

Classic or C corporations are subject to a different set of income tax rules from other types of businesses. If corporate profits were not taxed at all, every person in America might set up a corporation to shelter their income from tax. The complexity of corporate structures and transactions, however, makes taxing corporate income challenging, especially since large corporations frequently engage in cross-border activity. In addition, the rise of digital products and services—not to mention the impact of conducting business through the internet—have further complicated this picture.

The new tax law does little to address the challenges of taxing corporations. In fact, few loopholes were closed even as the tax rate on corporate income was slashed from 35 percent to 21 percent. Meanwhile, a new international tax structure was added on top of existing tax law, creating a wildly complex and illogical international tax regime that is ripe for gaming and that may encourage further offshoring and profit shifting.

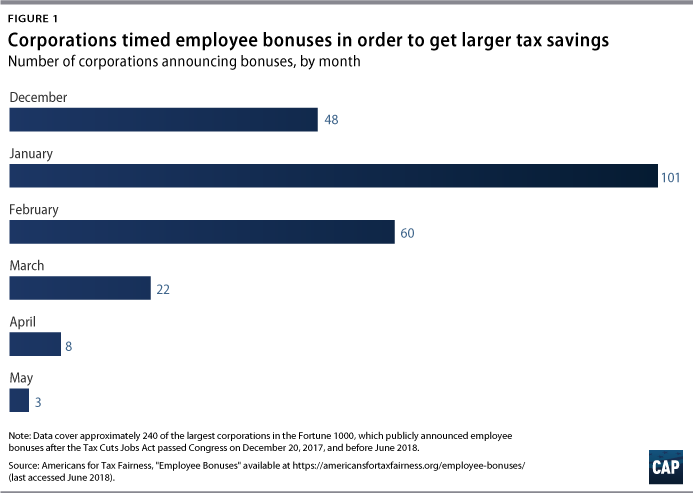

6. Corporations manipulating timing of worker bonuses and pension plan payments to maximize deductions

Under the new tax law, the reduction in the statutory corporate tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent became effective as of January 1, 2018. While corporations welcome the rate cut, it means that deductions taken in 2017 are worth more than deductions taken in 2018. For example, a $100 deduction at a 35 percent tax rate saves a company $35 of taxes, but a $100 deduction taken at the new 21 percent tax rate only saves $21 of taxes. This may explain why so many employers rushed to give bonuses before the end of 2017—not to share their huge tax cut with their workers, but rather to ensure that they received the biggest tax deduction possible for bonuses they would have given anyway.53 Offering the bonuses at the end of 2017 enabled corporations to receive a larger tax break since it reduced corporate income that would have been taxed at a 35 percent statutory tax rate.

It also explains why many firms chose to give one-time bonuses instead of permanent wage increases to their employees. Employee bonuses and wages are both deductible business expenses, but they are treated differently under tax accounting rules. When a corporation’s tax year crosses the calendar year, accounting rules allow for a blended rate, meaning the bonuses would be prorated, with part being deductible at the 2017 rate and part at the 2018 rate.54 Even for a calendar-year corporation, a 2017 bonus not paid until the first quarter of 2018 may still be deductible against 2017 income so long as certain tests are met, such as that all events have occurred establishing the employer’s obligation to pay the bonus.55 By contrast, a wage increase, in addition to being a company’s permanent commitment to its workers, would have been more clearly a 2018 expense and thus only deductible at the new, lower rate. By giving a bonus instead of a wage increase, therefore, corporations have been pulling compensation forward in order to save on taxes.56

Examining the bonuses announced so far from December 2017 to April 2018 suggests this may in fact be what is happening.

Corporations may also be accelerating other expenses for similar reasons. For example, corporations with underfunded pension plans that they would have had to fund anyway are also rushing to pay as much as possible into their plans now due to a timing loophole in the new law. If companies make the contributions before September of this year, they can take a deduction at the old, 35 percent corporate rate. In other words, just by moving forward a payment they would have to make anyway, they will receive a tax break worth $35 instead of $21 for every $100 contributed. Because many of the largest firms have tens of millions of dollars in pension obligations, the extra tax break will yield millions to these mostly large corporations. A spokesperson for one of those firms made clear that the tax law did not spur the decision to pay into the pension plan, but that the tax law did “encourage us to accelerate any such decision” in order to get the larger deduction.57

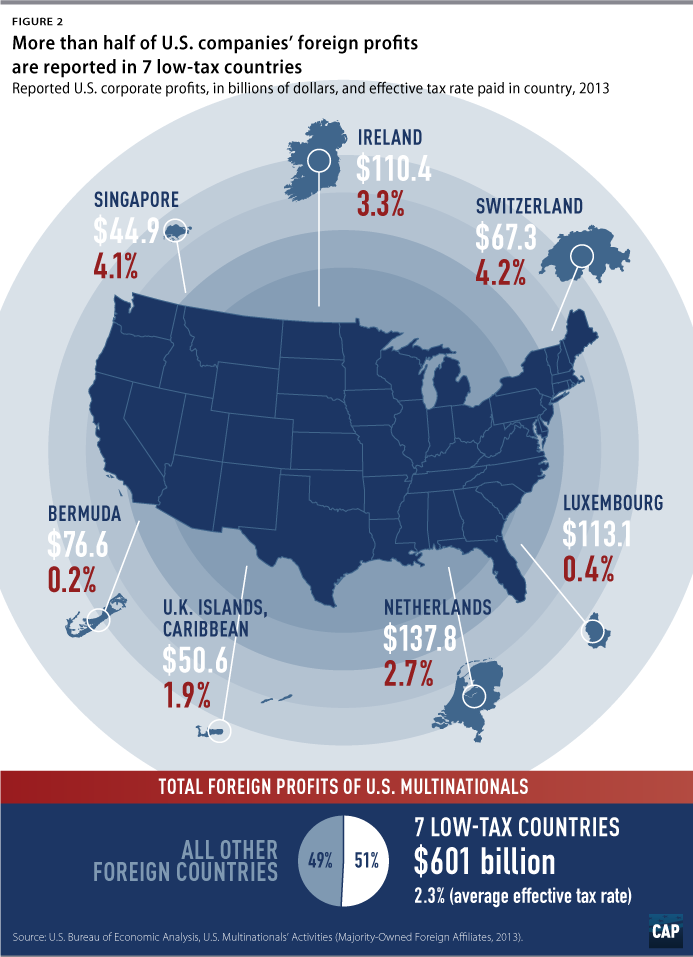

7. U.S. corporations investing more overseas to game the new international tax regime

Before the new law was passed, multinational corporations could defer paying U.S. tax on their foreign subsidiaries’ earnings so long as they did not bring the earnings back to the United States—or repatriate them.58 Repatriation typically is accomplished by having the foreign subsidiary pay dividends on the stock the U.S. company holds in the foreign company. Some multinationals amassed billions of dollars of earnings offshore that the United States has never taxed. In aggregate, untaxed earnings of U.S.-based multinationals amounted to $2.6 trillion in 2017.59

The new law allows corporations to bring future earnings from the foreign subsidiaries they control back to the United States tax-free. This aspect of the new international tax regime is referred to as territorial, since it purports to tax only profits earned in the United States.60 By not taxing the profits of foreign subsidiaries, the new law provides a strong incentive for U.S. companies to earn as much income as possible offshore.61 It is a significant concern—especially with respect to technology and pharmaceutical companies that can easily transfer ownership of software licenses, patents, and other intellectual property to foreign subsidiaries, which then receive the income from these assets. Supporters of the new tax law, however, maintain that the law’s new anti-abuse measures will prevent this from happening.

The primary backstop to the territorial system under the new tax law is a minimum tax on high foreign profits aimed specifically at mobile assets such as software, patents, and other intellectual property. This is called the global intangible low-taxed income (GILTI) tax.

A certain amount of foreign income is exempt from the GILTI minimum tax. But the amount of the exemption is calculated based in part on how much income a company has overseas from tangible property, such as manufacturing facilities or retail stores. In effect, the more tangible property, the lower the U.S. GILTI tax. As minority staff of the U.S. Senate Committee on Finance explain in detail in a recent report, the resulting effective tax rate on the offshore earnings is likely to be significantly lower than the tax rate on domestic earnings—a gap in rates that will invite gaming.62 Thus, under this supposed backstop, there is an incentive for firms either to move tangible property offshore or to acquire more tangible property in foreign countries where they earn profits. An example of the latter might be if a U.S. corporation purchased a string of restaurants in countries where it has foreign profits.63 Income from these acquired tangible businesses, or newly established operations, effectively would shield the corporation’s intangible foreign income from the GILTI tax.64

8. U.S. multinationals averaging global profits in order to continue exploiting offshore tax havens

Under the new law, U.S. multinational corporations can still reduce U.S. GILTI tax they owe on foreign earnings by any foreign taxes they paid on that foreign income, within limits. The new GILTI tax allows multinational corporations to blend credits for foreign taxes on a global basis—rather than country by country. Thus, taxes paid on earnings in a high-tax country can effectively offset very low-taxed earnings in a tax haven, thereby reducing or even eliminating any GILTI tax due.65 In fact, this method of blending foreign tax credits may even encourage firms with high profits in tax havens to invest in countries with higher tax rates than the United States, since the extra foreign taxes paid in the high-tax country would essentially use up the tax haven profits.66 When former President Barack Obama proposed a minimum tax on foreign earnings during his administration, the proposal called for calculating the tax on a per-country basis so that multinational corporations could not average taxes across countries. But the new law’s loophole allowing firms to average foreign tax credits globally means there is no need for U.S. corporations to stop shifting profits to tax havens. This is a feature—not a bug—of the new tax system, which allows this form of gaming to continue, just through a different calculation.

9. U.S. corporations manipulating cost of goods sold to avoid anti-abuse tax

Prior to the passage of the new tax law, congressional Republicans and Democrats alike decried U.S. corporations’ widespread practice of shifting profits offshore instead of investing profits in the United States.67 The corporations accomplished this, for example, by borrowing funds from their foreign subsidiaries to which they would owe interest or by transferring ownership of income-producing intellectual property such as patents and copyrights to their foreign subsidiaries. The U.S. corporation would make deductible interest or royalty payments to the foreign subsidiary, thereby reducing its U.S. taxable income. Profit shifting has been estimated to cost the U.S. Treasury more than $100 billion annually.68

Proponents of the new law claim that a guardrail in the law will discourage profit shifting—the base erosion and anti-abuse tax (BEAT). The BEAT taxes transfer payments from a U.S. firm to its foreign affiliates.

But the BEAT does not apply to expenses on a company’s books that are considered cost of goods sold (COGS), which consist generally of raw material and labor expenses but can also include other expenses. Shaviro predicts that moving expenses into the COGS category will be a “central tax-planning focus.”69 And, in fact, tax experts from high-level law and accounting firms already are discussing such opportunities at conferences on the new tax law.70 Jane Gravelle, an economist with the Congressional Research Service, describes some of these games in a recent report.71 Gravelle notes, for example, that if a U.S. firm pays its foreign parent both for tangible property that it will sell in the United States and for royalties in connection with the logo on the products, the firm could drop the royalty fees and increase the amount paid for the products. The same amount of money would be transferred from the U.S. firm to the foreign firm, but the taxable royalties would instead be embedded in the nontaxable COGS, thus avoiding the BEAT. Firms could also restructure their supply chains in order to game the BEAT through the COGS loophole.

10. Corporations getting a bigger FDII deduction by round-tripping goods

In another supposed guardrail, the new law uses an incentive approach to discourage corporations from transferring income-producing intangible assets, such as patents and copyrights, to low-tax countries. These types of assets are highly mobile, requiring only electronic transfer in many cases. Under the new law, if the company keeps the intangible asset in the United States, it can deduct a large portion of any income it receives from foreign companies that pay for the right to use the asset. For example, if a technology company decides to retain its software licenses in the United States, it will get a large tax cut on the income it receives from foreigners who pay to use the software. This deduction for foreign-derived intangible income (FDII) effectively cuts U.S. tax on that income roughly in half.

Unfortunately, the FDII deduction potentially violates World Trade Organization rules as an inappropriate export subsidy.72 In addition, as the Senate Committee on Finance staff demonstrates in its report, the effective tax rate it offers is actually not as low as the effective tax rate achievable on foreign income under the GILTI tax; thus, corporations may prefer to shift assets and production offshore.73

The FDII deduction also invites gaming. Tax experts have observed that corporations may be able to use so-called round-tripping in order to characterize more of their domestic income as eligible for the deduction.74 In order to generate export sales income, a corporation that otherwise would sell its products to U.S customers could instead sell the products to an unrelated foreign company, thereby generating a FDII deduction. Thereafter, the U.S. firm’s foreign subsidiary could repurchase the products from the unrelated firm and sell them to the U.S. customer.75 There are potentially more sophisticated round-tripping transactions, and these would be more difficult for the IRS to police.

11. Big businesses relocating debt to foreign subsidiaries to avoid the limit on interest deductions

The 2017 tax law imposed a new limit on the deductibility of interest on business debt. Corporations and other businesses with average annual gross receipts of $25 million or more can only deduct net interest expenses up to 30 percent of their adjusted gross income, with certain adjustments. The allowable net interest deduction is further reduced from 2022 onward.76

Theoretically, the limit on the interest deduction would discourage businesses from relying too heavily on debt to finance their operations and investments. Tax advisers for U.S. multinational corporations, however, are considering ways to skirt the interest deduction limit—ways not available to small businesses. One way that at least two firms have already tried is to borrow through the company’s foreign subsidiaries in situations where a U.S. corporation’s debt would otherwise exceed the cap.77 The foreign subsidiary, ideally in a higher-tax country, can take out a loan in their country and may be able to deduct the interest payments against taxes in that country. Thus, the multinational merely changes the location of its debt rather than reducing its debt overall.

Conclusion

In their rush to deliver huge tax cuts to wealthy individuals and businesses and big corporations, the proponents of the TCJA passed a sweeping bill with an unprecedented number of mistakes, ambiguities, and loopholes—opening the door to increased gaming of the nation’s tax system. Wealthy individuals and profitable corporations, with the help of their well-paid tax advisers, will be in the best position to take advantage of the gaming opportunities. The associated revenue loss will further threaten funding for infrastructure improvements, education, Medicare, and other federal initiatives that ensure broad participation in the U.S. economy over the long run, as well as economic stability. Left unchecked, tax gaming will both undermine trust in the tax system and exacerbate inequality in America.

About the author

Alexandra Thornton is the senior director of Tax Policy for Economic Policy at Center for American Progress.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge Galen Hendricks, special assistant for Economic Policy at the Center for American Progress, who helped with the figures in this report. The author also would like to thank Steve Rosenthal and Seth Hanlon for their insightful comments on earlier drafts.