This summer, President Barack Obama asked a simple question: “In a country where we expect free Wi-Fi with our coffee, why wouldn’t we have it in our schools?”

If a coffeehouse has slow Wi-Fi, the consequences generally aren’t substantial—you might not be able to Skype with your friend in England while sipping your latte, for example—but the lack of technology in our schools has significant implications. Schools need robust digital tools to give students the knowledge and skills to succeed—just imagine a high school graduate arriving at college not knowing how to use Excel. But more than that, technology is increasingly key to making schools more effective. Tests, for instance, can now be given online to provide a much more accurate measurement of student achievement. Teachers can also use software to enrich learning and make grading homework much easier.

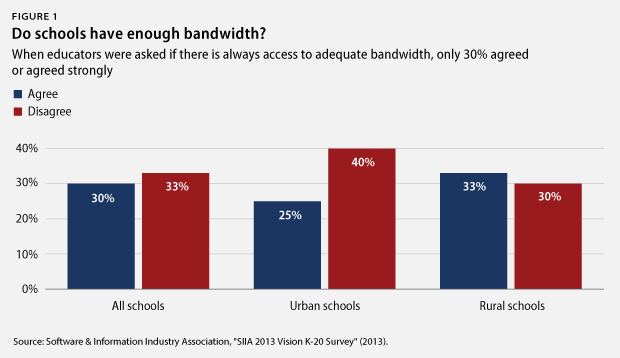

However, schools and districts across the country desperately lack technological capacity. When we recently studied unpublished data from the Software & Information Industry Association’s 2013 Vision K-20 Survey, for instance, we found that 70 percent of educators believe that there is simply not enough bandwidth in their schools. What’s more, it appears that urban schools often have the least access to bandwidth.

The good news is that President Obama has been a leader on this issue, and his ConnectED initiative aims to connect 99 percent of America’s students to the Internet through high-speed broadband within the next five years. The president’s program would also help train teachers and level the playing field between high- and low-poverty schools. According to his plan, ConnectED would build on the E-rate program, which Congress created in 1996 to provide schools and libraries with low-cost telecommunications services.

Furthermore, some efforts to improve school connectivity are already underway. During his State of the Union address, President Obama announced that the Federal Communications Commission, or FCC, and several private companies signed on to support his ConnectED initiative to help schools build higher-speed Internet connections. More details emerged last week about this support, with the president revealing that private firms will contribute more than $750 million to increase high-speed Internet access and technology in schools. FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler also explained how the FCC plans to devote an additional $2 billion in E-rate funding to help some 15,000 schools build higher-speed Internet connections using existing funds.

This recent progress is not enough, however, and the FCC needs to do more to revamp and more generously fund E-rate. Why? In short, the E-rate program today is a lot like a dial-up modem. It’s balky, complicated, and lacks power. The application process, for example, is slow, burdensome, and keeps many eligible school districts and libraries from applying—or forces them to hire outside consultants to help guide them through the process.

Plus, the program simply lacks funds and will remain underfunded even if the FCC provides an extra $2 billion over the next two years. Consider this: The E-rate program was capped at just over $2.38 billion for 2013, yet schools and libraries requested more than $4.9 billion in E-rate funding this past year. In other words, schools are far from having the digital access they need.

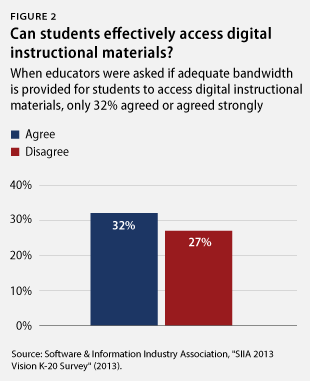

This fact was supported in the Software & Information Industry Association survey, which found that less than one-third of educators—25 percent of educators in urban areas and 33 percent of educators in rural areas—believe that there is adequate bandwidth for students to have access to digital instructional materials.

Schools and districts also lack the capacity to use technology in creative ways. In our analysis of federal government data, for instance, we found that as recently as five years ago, only around half of all school districts had a full-time technology coordinator. More than that, wealthier schools were 13 percentage points more likely to have a technology coordinator than poorer schools. In other words, the schools that needed the most support were the ones getting the least.

Technology alone will not revolutionize our nation’s school system. We also have to address myriad other education issues, from teacher training to lengthening the school day and year. But when it comes to schools, technology has become a crucial way to make education have a far greater impact, and we need to do a lot more as a nation to bring our schools out of the digital dark ages and into the 21st century.

Ulrich Boser is a Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress. Chelsea Straus is a Research Assistant for the Pre-K-12 Education Policy team at the Center.