For years the conventional wisdom has said that “gun control” is a deeply polarizing and divisive issue and that support for stronger gun laws has been declining. In the wake of the December shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, however, a wealth of new data challenges this conventional wisdom. First, public opinion has shifted significantly. By many measures, support for stronger gun laws has substantially increased. Second, signs of an emerging national consensus on many gun issues—which was actually developing prior to the Newtown shooting—are also evident.

In this issue brief—co-authored by a bipartisan team of pollsters who have each conducted public-opinion research on attitudes toward guns in recent years—we hope to set the record straight and provide tools for polling outlets and reporters going forward. We’ll focus on three key points:

- Newtown changed the debate. The Newtown shooting had a greater impact on public opinion about guns than any other event in the past two decades—and led to a clear rise in public support for stronger gun laws. In particular, three aspects about public opinion in the wake of Newtown are notable:

- Near unanimous support for universal background checks and clear majority support for high-capacity magazine and assault-weapons bans

- Almost as much support for stronger gun laws among gun owners as among the general public

- A large gender gap in views on guns and violence

- Much of the pre-Newtown polling missed emerging trends of Americans’ views on gun issues. Even before the Newtown shooting, Americans were less divided than some polling suggested because much of the polling contained the following three kinds of errors, omissions, or oversights:

- Overly broad questions on gun views failed to capture nuances in public opinion

- Outdated policy questions about guns missed the current debate

- Outdated language to describe gun issues failed to capture voter attitudes

- There is an emerging consensus on guns among the American public. Most Americans agree that handguns should not be banned, that more needs to be done to keep guns away from dangerous people, and that military-style weapons don’t belong on the streets.

Below, we look at these key points in more detail.

Newtown changed the debate

Most public polling on guns is conducted in the aftermath of a mass shooting, so it can be difficult to parse out what is a post-shooting reaction and what is the more stable public opinion. But the Newtown shooting has changed public opinion on guns in ways that the shootings at Columbine High School, Virginia Tech University, and in Tucson, Arizona, did not.

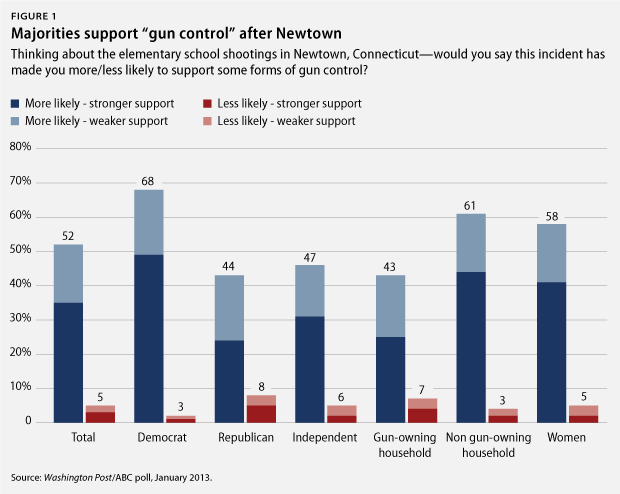

Americans across demographic groups report that Newtown has changed their views. In a January Washington Post/ABC News poll, a majority of Americans—52 percent—say they are now “more likely to support some forms of gun control,” with twice as many—35 percent—”much more likely” than “somewhat more likely”—17 percent. Even 44 percent of Republicans and 43 percent of Americans in gun-owning households said that they are more likely to support some stronger gun laws. Only a handful of voters overall—5 percent—say that they are less likely to support stronger gun laws. (see Figure 1)

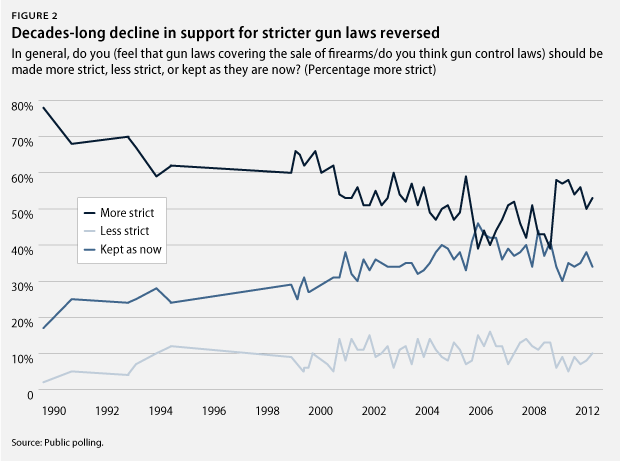

Likewise, in each polling outlets’ broad-climate questions, support for stronger gun laws increased in the immediate aftermath of Newtown and continues to increase a month or more later. Gallup, for example, typically asks a three-pronged question: Should laws be “more strict, less strict, or kept as they are now?” Other outlets have a similar formulation. This version of the question has shown a decline in “more strict” responses over the years, but those numbers have recently stabilized. In the wake of Newtown, support for stricter laws has jumped more than at any time in the last two decades. (see Figure 2)

And though the National Rifle Association, or NRA, may be waiting for the “Connecticut effect” to dissipate, support for stronger gun laws remains high, with many polls showing majority support for stricter gun laws a month—and in some cases nearly two months—after Newtown. In fact, some public opinion research suggests that support for stronger gun laws has not only maintained its post-Newtown bump but also that support is continuing to rise.

An NBC News/Wall Street Journal poll found that in mid-January, a month after Newtown, 56 percent of Americans supported “stricter” gun laws, as opposed to the 35 percent who wanted laws kept as they are and the 7 percent who wanted laws weakened. Two months after Newtown the same poll showed that support for stricter laws had increased to 61 percent, with only 4 percent of Americans favoring weaker laws and 34 percent wanting current laws to be maintained.

There is near unanimous support for keeping guns out of dangerous hands

When pollsters drill down to particular policy proposals, almost all voters want to keep guns out of dangerous hands. In every poll where these measures are tested, support for appropriate measures is strong and consistent—and transcends party lines.

Background checks: Voters support criminal background checks of essentially all kinds—for every gun purchase, at gun shows, for ammunition, and others. Support for these proposals is nearly unanimous—and has been in every poll we’ve seen. There is also nearly unanimous support for specific measures to keep felons, the mentally ill, drug abusers, those with arrests for domestic violence, and those on the government’s terrorist watch list from purchasing guns.

High-capacity magazines and assault weapons: A smaller but a consistent majority of voters supports bans on high-capacity magazines, assault weapons, and other perceived safety threats. The major pieces of President Barack Obama’s package requiring congressional approval—a ban on high-capacity magazines and assault weapons—are more popular than media coverage would suggest. A ban on high-capacity magazines is consistently popular with a majority of voters. Results have fluctuated little over the decades of public polling—between majority support and two-thirds support. In the January Washington Post/ABC News poll, 59 percent of Republicans say they supported such a ban. The only stronger gun law currently being discussed that has occasionally received less than majority support is an assault-weapons ban, but that proposal usually receives majority support. On average, support for a high-capacity magazine ban exceeds support for an assault-weapons ban by five points.

Table 1 below shows recent results across polling outlets for some of these proposals. For full question wording and polling methodology, please see the endnotes.

Support for action is high even among gun owners

Polling shows that support for strong gun measures is high among gun owners. Support for requiring criminal background checks for all gun sales—no matter who the seller is or where the location of the sale is—receives not only near-universal support among the general public but also among gun owners. (see Table 2)

On other policy questions, a gap between the opinions of the overall public and gun owners develops—but perhaps not as wide as one might expect. On the question of assault weapons, for example, a December Pew Research Center poll found that about two-thirds (65 percent) of Americans think, “allowing citizens to own assault weapons makes the country more dangerous.” Half (50 percent) of those in a gun-owning household agree. Likewise, while a February Quinnipiac poll shows that 56 percent of Americans support bans on assault weapons and high-capacity magazines, support among gun owners trails 12 points and 11 points behind, respectively.

Perhaps most troubling for NRA leadership is that a majority of respondents—61 percent—in a recent Gallup poll say that the NRA does not reflect gun owners’ views on guns. Even in gun-owning households, 49 percent of respondents say that the NRA reflects their views “only sometimes/never,” while 50 percent of respondents answer “always/most of the time.” The NRA’s distance from gun owners suggests the organization is out of touch with its own constituency. And voters agree. A February Public Policy Polling poll shows that 39 percent of Americans said that the NRA’s support would make them less likely to support a candidate for office, while only 26 percent said the NRA’s support would make them more likely to support a candidate.

An important gender gap

With women voters increasingly crucial to electoral success, a gender gap on guns means the issue can drive the political dialogue. Women are more supportive of stronger gun laws broadly and more likely to support specific proposals. The gender gap transcends party affiliation.

In the wake of Newtown, CBS News and The New York Times, Public Policy Polling, and the Pew Research Center each show a double-digit gender gap in support of stronger gun laws, with approximately 6 in 10 women supporting such a change. Both Pew and Gallup tracking suggest that this gender gap dates back to the 1990s.

The gap pervades every proposal tested. The mid-January Washington Post/ABC News poll showed that support for a ban on assault weapons and high-capacity magazines runs 16 points and 15 points higher, respectively, among women than it does among men. Pew shows a similar result. In fact, both polls show majorities of women support every single specific stronger gun law tested, aside from arming teachers. (For more on this gender gap, see this piece by co-author Margie Omero.)

While conventional wisdom may say that the NRA is a well-liked organization, that is simply not true among women. In mid-January the Washington Post/ABC News poll showed men slightly favorable toward the “NRA leadership,” while women were unfavorable by a nearly 2-1 ratio. Similarly, Public Policy Polling found women unfavorable to the group even before the December press conference in which NRA CEO and Executive Vice President Wayne LaPierre defended guns and called for more armed guards in schools as a response to reducing gun violence.

Furthermore, a February 2013 bipartisan poll of women voters for the Women Donors Network—conducted by co-authors Bob Carpenter and Diane Feldman—showed the NRA to be the least influential person or group on women’s views on guns. Even women in NRA-member households rated parents and “women like themselves” more highly as spokespersons than they rated the NRA.

One likely driver of this gender gap is women’s concern about violence in their communities. After Newtown, both the Washington Post/ABC News poll and Gallup showed that about 6 in 10 women worried about a mass shooting, compared to less than half of men. And the Women Donors Network survey cited above showed that women were concerned about a broader culture of violence—and that 23 percent of likely voting women had themselves been a victim of physical violence or physical abuse or had a family member who was a victim.

Missing the emerging consensus: Three problems with the pre-Newtown polling

The Newtown shooting has changed Americans’ views on guns, but there is reason to suspect that support for action was stronger before Newtown than major polling outlets and the resulting media coverage suggested. Too much of the pre-Newtown polling suffered from three kinds of problems:

- Over-reliance on broad, overall “climate” questions, with too few policy drilldowns

- Over-reliance on outdated policy questions

- Over-reliance on the outdated phrase “gun control”

Over-reliance on broad, overall “climate” questions

Some standard questions on views toward gun laws are overly broad and point to inconsistent conclusions.

One of the most consistent findings in gun polling is that support for “gun control” broadly is lower than support for specific tighter gun laws. One reason is the lack of specificity in broad “gun climate” questions. What do respondents think of when asked whether they support “gun control” or “stricter laws covering the sale of firearms”? Are they thinking about a ban on all guns, including hunting rifles? Are they thinking about preventing people accused of domestic violence from getting a gun at a gun show without a background check and then bringing that gun across state lines? We simply don’t know. This is not to say that a broad question on attitudes toward gun laws can’t be useful, but we should simply understand its limitations.

One challenge is interpreting the results in the current policy context. Even though polling outlets structure their broad climate questions differently, they consistently show support for some sort of restrictions on guns. The CNN/ORC poll shows that about three-fourths of Americans want to see at least minor restrictions on guns. (see Figure 4) And the three-pronged climate questions asked by most outlets consistently show hardly any support for making gun laws “less strict.” (see Figure 2) Yet before the Newtown shooting, the NRA, the American Legislative Exchange Council, and others were indeed fighting for less strict gun laws, inching us closer to the “no restrictions” end of the spectrum.

Furthermore, while it’s true that prior to Newtown support for stronger gun laws had declined from the 1990s, in all broad climate questions, support for specific policies remains high.

The table below shows the degree to which support for specific policies exceeds support for the generic notion of “stricter gun laws.”

Over-reliance on outdated policy questions

In 2008 the Supreme Court held in the landmark District of Columbia v. Heller case that the Second Amendment guaranteed an individual the right to own a handgun in their home for self-defense. The ruling made clear that this right was subject to reasonable regulation, but it also meant that a complete ban on handguns was off the table. In fact, long before the 2008 decision, no serious national politicians and very few local elected officials were advocating banning handguns. But that didn’t stop some polling outfits from asking questions about support for handgun bans.

Between the Columbine High School massacre in April 1999 and its most recent post-Newtown poll, Gallup asked Americans about support for a ban on handguns 13 times. Over that period support for such a policy dropped from 38 percent to a record-low 24 percent in December 2012. That drop in support preceded the landmark 2008 Supreme Court Heller decision but accelerated after the Supreme Court ruled that such a policy was constitutionally impermissible. Gallup kept asking this question even though no legislation to ban handguns was introduced in Congress—let alone debated—at any time during the period.

In the wake of Columbine and over the past 14 years, the policy perhaps most debated and prioritized by advocates for stronger gun laws is closing the loophole at gun shows or completely closing the private-party-sale background-check loophole. This policy was seriously debated in states—a number of which adopted this measure—and in Congress, where it was voted on in 1999 and 2004 and received more co-sponsors in recent years than any other gun-law-strengthening measure. But Gallup has asked about closing gun-sale background loopholes just three times since 1999: once two months before Columbine, when it received 83 percent support; once a few months after Columbine, when it received 87 percent support; and then again in December 2012, when support rose to 92 percent. This near-universal support for universal background checks is consistent with other public polls, as seen in Table 1.

Over-reliance on the outdated phrase “gun control”

Advocates for stronger gun laws have long abandoned the word “control.” No national group currently advocating for stronger gun laws currently uses the word. The group called Handgun Control changed its name to The Brady Campaign to Prevent Gun Violence more than a decade ago. And more recently the group Million Moms for Gun Control changed their name to Moms Demand Action. No poll commissioned by a gun-law group includes the word. Internal polling in 2011 for a group working for stronger gun laws showed “gun control groups” receiving weaker ratings than “gun violence prevention groups.”

“Control” has been dropped for a reason: It is aggressive rather than neutral. It sounds as if “control” alone is the objective, and it helps paint the incorrect picture of government “coming for” one’s guns. And you’d be hard pressed to think of another set of laws that uses the word. Despite all this, “control” remains in the common vernacular.

Looking at the exact question wording in every outlet’s version of the three-pronged broader climate gun question—should laws be made more strict, less strict, or kept the same—only CBS News/New York Times and the Los Angeles Times use the phrase “gun control” in the question. Other outlets use “sale of firearms” or similar wording. And the CBS News/New York Times and Los Angeles Times results consistently show lower “more strict” support than the other outlets. It’s certainly possible that there are house effects at work, in which the CBS News/New York Times and Los Angeles Times polling methodology are consistently and similarly different from the other outlets, but this pattern has been evident since 1999, the earliest year for which data are available for comparison.

Simply using the phrase “gun laws” or “stronger gun laws” is a neutral, appropriate phrase, and it should be part of all public polling and public discussion going forward.

In Pew’s question, respondents are asked, “Which is more important, to control gun ownership, or protect gun rights?”, as if controlling gun ownership is its own goal—as opposed to, quite obviously, reducing gun violence—in the way that protecting gun rights is its own goal. Even in this question, however, support for “controlling gun ownership” has stabilized in the last few years and—after Newtown—now exceeds support for protecting gun owners’ rights.

The real frame for a broader gun-climate question should ask respondents to choose between gun rights on the one hand and reducing gun violence on the other. Yet only internal polling for gun-law advocates has this frame in its wording.

Widespread, stable support for a common ground on guns

There is clear consensus around a variety of common-sense gun laws, as well as consensus around what limits are unacceptable. Congress is fighting over questions that are simply not controversial.

The common ground is centered on the following two ideas:

- Responsible law-abiding Americans have a right to own guns.

- Much more needs to be done to keep dangerous guns from dangerous people.

Pollsters have too often asked questions that present these two ideas as opposing; the vast majority of Americans view these concepts as consistent and complementary.

Americans overwhelmingly agree with the Supreme Court that the Second Amendment protects the rights of individual Americans to own a gun. While the wording varies slightly across outlets, the results are consistent. About three-fourths of voters feel the Constitution protects all—or most—Americans’ rights to own a gun, not just the rights of militias. And despite gun-lobby histrionics, there is no mandate in the public or among policymakers to “attack” the Second Amendment.

Americans also agree that much more ought to be done to keep dangerous guns from dangerous people. In July 2012 polling for Mayors Against Illegal Guns, Republican pollster Frank Luntz found that 87 percent of NRA members and 83 percent of non-NRA gun owners agree that, “Support for Second Amendment rights go hand-in-hand with keeping illegal guns out of the hands of criminals.” And in 2009 Luntz polling—also for Mayors Against Illegal Guns—found that 86 percent of NRA and 86 percent of non-NRA member gun owners agree with the following statement: “We can do more to stop criminals from getting guns while also protecting the rights of citizens to freely own them.”

The American voter’s penchant for balance and compromise extends to gun laws. Across lines of gun ownership, gender, and party, there is more support for some stronger laws than the status quo. Only a careful read of the polling identifies the fault lines that invariably exist, along with the common ground that also exists just as assuredly.

The authors of this paper are principals at public opinion research and strategic consulting firms. Margie Omero is president of Momentum Analysis. Bob Carpenter is president of Chesapeake Beach Consulting. Michael Bocian is a founding partner at GBA Strategies. Diane Feldman is president of The Feldman Group, Inc. Linda DiVall is founder and CEO of American Viewpoint. Douglas Schoen is a Democratic campaign consultant. Celinda Lake and Joshua Ulibarri are president and partner of Lake Research. Al Quinlan is president of Greenberg Quinlan Rosner Research. Arkadi Gerney is a Senior Fellow at the Center for American Progress.