An all-too-common response to workers and advocates concerned about the 23-cent gender wage gap for full-time year-round workers across occupations is that it is just a byproduct of the choices women make: choices to work fewer hours, take on lower-paying jobs, or opt out of the workforce for longer periods of time than men. When framed in this way, it’s easy to dismiss equal-pay policies or legislation as superfluous. After all, we can’t force women to apply for higher-paying jobs or to work longer hours, right?

Unfortunately, decades of evidence have revealed a far more complicated story, and it is clear that the gender wage gap is about more than just personal choice. It is a real and persistent problem, and it is a problem that calls for immediate and nimble policy solutions. But in order to achieve pay equity, it helps to understand the origins of the gap.

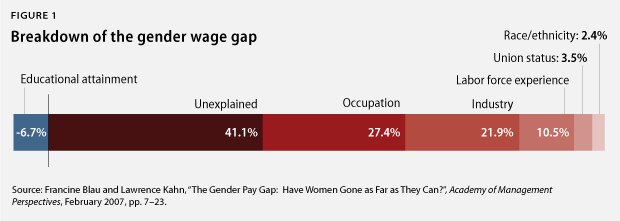

Among men and women employed full time, 60 percent of the wage gap can be attributed to known factors such as work experience at 10 percent, union status at 4 percent, and the aforementioned choice of occupation at 27 percent, among other measureable differences. (see Figure 1) A woman’s work experience is abbreviated if she needs to take maternity leave or take time off from a job to care for a child, which she is more likely to do than her male counterpart. Another quarter of the wage gap is attributable to the differences in wages paid by industries that employ mostly men or mostly women. These include blue-collar industries such as mining, manufacturing, and construction, which generally employ men, and service-sector or clerical jobs, which generally pay less and employ more women.

One mitigating factor that has actually reduced the gender wage gap is women’s access to higher education. This has helped ease the disparity by nearly 7 percent, as shown in Figure 1, but women’s access to college and advanced degrees has not been enough to close the gap completely. Women need an additional degree in order to make as much as men with a lower degree over the course of a lifetime. A woman would need a doctoral degree, for instance, to earn the same as a man with a bachelor’s degree, and a man with a high school education would earn approximately the same amount as a woman with a bachelor’s degree.

But what causes the remaining gap of more than 10 cents on the dollar—or $4,465 per year among workers making the median wage—between men and women? This is less clear but perhaps more troubling. More than 40 percent of the gender wage gap is “unexplained,” meaning that there is no obvious measureable reason for a difference in pay. This leaves us with possible explanations that range from overt sexism to unintentional gender-based discrimination to reluctance among women to negotiate for higher pay.

Whatever the reasons, a woman should have recourse if she is being paid less than her male counterpart for the same job. Passing the Paycheck Fairness Act and establishing a commission to address the gender pay gap would both be important steps toward achieving this goal.

Jane Farrell is a Research Assistant for Economic Policy at the Center for American Progress. Sarah Jane Glynn is a Senior Policy Analyst at the Center.