Albert Gray has probably had better days than June 17. As the executive director of the Accrediting Council for Independent Colleges and Schools, or ACICS, Gray heads one of the small nonprofit agencies that the U.S. Department of Education tasks with evaluating higher education institutions to determine which colleges are qualified to offer federal grants and loans to their students. On that day, Gray had been called before the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee to talk about ACICS’ role in ensuring quality in postsecondary education.

What happened during Gray’s testimony was as close to a viral moment as obscure postsecondary policies can come. In a video that’s since been viewed more than 290,000 times on Facebook, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) repeatedly challenged the role of Gray and his agency in overseeing Corinthian Colleges, a publicly traded company that closed for good in late April after the Department of Education forced it to start winding down in 2014. Similarly, Sen. Chris Murphy (D-CT) told Gray that his defense of ACICS’ actions showed that he was “living on a different planet than everyone else who reviews the track record of Corinthian.”

Senators grilling Gray about his role in overseeing a fraudulent multibillion-dollar operation encapsulates the odd way that quality assurance works in postsecondary education. Despite the fact that ACICS is a small nonprofit with just 50 employees and $15 million in revenues, its decisions affect how billions of federal dollars are spent. A positive accreditation decision by ACICS grants a college access to all major federal student loan and grant programs, which is worth millions of dollars and serves as the lifeblood for most institutions. Taking this approval away can be a deathblow.

But among the colleges that ACICS approved for federal aid are several dozen that Corinthian Colleges had owned at some point. Corinthian was built on a business model of recruiting low-income and minority students to attend expensive programs of questionable quality that were largely paid for with student loans. The federal government is still trying to clean up the mess the company left behind by forgiving the loans of defrauded students—a process that will likely cost taxpayers millions, if not billions, of dollars in addition to the $3.5 billion the company received from the federal government over the past five years.

Despite years of warning signs, ACICS took minimal action against Corinthian Colleges. In April 2014—while the Department of Education was actively investigating the company for its questionable job placement rates and just a few months before the department acted to start Corinthian’s closure—ACICS renewed the accreditation of two Corinthian campuses and authorized a new branch campus. Gray continued to defend his agency’s actions even after the company closed, noting at the Senate hearing that ACICS found no evidence of the college lying to its students or committing fraud.

Although ACICS has received—and should continue to receive—scrutiny for its oversight of Corinthian, a new Center for American Progress analysis suggests that concerns about the accreditor’s role in ensuring college quality extend beyond this one educational provider. According to the analysis, one out of every five borrowers at an ACICS-accredited college defaults on his or her loans within three years of entering repayment—a mark that is 50 percent higher than the national average. Such high default numbers are particularly troubling because students at ACICS-accredited colleges take out student loans at higher rates and in greater amounts than those at colleges accredited by other agencies.

While ACICS’ performance is worse than that of its peers that provide similar gatekeeping functions, CAP’s analysis suggests that problems with ACICS are emblematic of larger structural flaws that exist in this national accreditation space, which is mostly focused on career education. This is not an arcane policy matter. As the gatekeepers to federal student aid, accreditors’ lax approval standards can open the door to mass fraud that undermines confidence in loan programs and the broader postsecondary education system. The role of accreditation and quality assurance is also likely to be a major topic of discussion in the upcoming reauthorization of the Higher Education Act, as well as the 2016 presidential election. On one side, there are concerns similar to those Sen. Warren raised at the Senate hearing over accreditors’ ability to properly protect consumers. On the other side, individuals such as Sen. Marco Rubio (R-FL) have called for rethinking accreditation to allow for more innovative postsecondary education providers. Although these concerns come from different sides of the argument, they lead to the same outcome—a sense that the way in which accreditors determine who enters and exits federal student aid programs needs improvement.

Accreditation and its types

Gaining access to the federal student aid programs is a multistep process for colleges and universities. In addition to needing approval from a state and the U.S. Department of Education, they also must be accredited. To become accredited, an institution must be approved by 1 of the 37 agencies that the Department of Education recognizes to serve as gatekeeper to federal grant and loan program access. Agencies are supposed to visit campuses and conduct in-depth investigations of things such as teaching and learning practices, facilities, faculty, and a host of other issues. In that regard, they are expected to take a much closer look at what actually occurs in a given school with respect to learning than any other part of the higher education oversight structure.

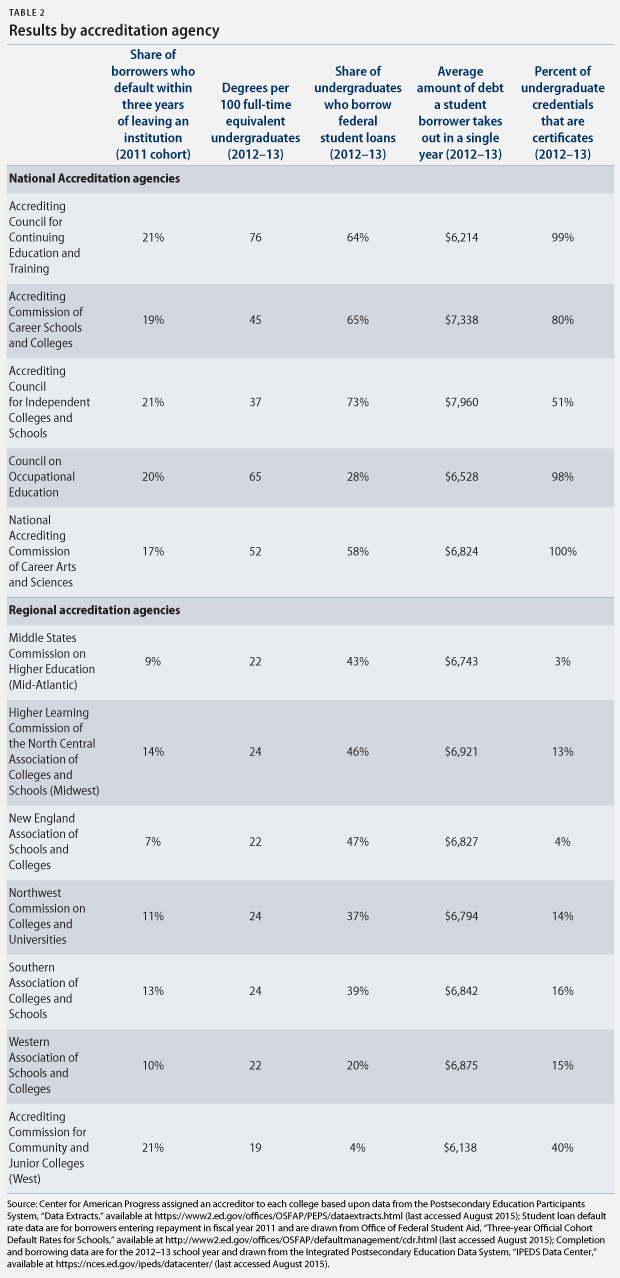

While approval from any accreditation agency authorized to serve as a gatekeeper is sufficient for a college to offer federal loans and grants, there are several different types of accreditors. The largest are known as regional accreditors: There are seven regional accreditors in the United States, and each represents a specific geographic area. (see Table 2 for full list of regional accreditation agencies) For example, colleges in the Mid-Atlantic have to be accredited by the Middle States Commission on Higher Education to gain regional accreditation, while colleges in the South need to be accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools. In general, the vast majority of public colleges have regional accreditation, as do all prestigious nonprofit institutions. That being said, regional accreditors also accredit some private, for-profit colleges, including large national chains such as the University of Phoenix and Strayer University.

National accreditation is the second most common type of accreditation. National accreditors are not limited to any given part of the country but tend to have a more specific focus than regional accreditors. For example, some national accreditors only approve career colleges, while others focus on bible colleges or art schools. The majority of schools with national accreditation are private, for-profit colleges—often those that offer career-focused programs.

National accreditors can fill the gatekeeper role for federal student aid in two main ways. Some, such as ACICS, are able to perform this function for any college. Others, such as the Accrediting Bureau of Health Education Schools, or ABHES, can only grant a college access to federal aid if it is a standalone college in their field. In other words, ABHES can approve the Foley, Alabama, campus of Fortis College for federal aid because it only focuses on health care, but it cannot do so for Penn Foster College in Scottsdale, Arizona, because it offers other non-health care programs as well.

Depending on the situation, the type of accreditation both does and does not matter. From the perspective of federal student aid benefits, it is not relevant; Princeton University gets access to the same suite of grants and loans as Jay’s Technical Institute, a Houston barber school. From the colleges’ perspective, however, it does matter. Many regionally accredited colleges are reluctant to accept credits from nationally accredited institutions; this is at least partly due to concerns about the quality of those schools. As a result, students may attempt to transfer from one college to another under the impression that their credits—like their loans—will move freely, only to find that differing accreditation status may mean this is not the case.

About CAP’s analysis

CAP’s analysis looks at results for ACICS and the other four national accreditors that approve entire colleges, as well as the seven regional accreditors. Performance data are drawn from several federal data sources. The U.S. Department of Education’s Postsecondary Education Participants System, or PEPS, was used to identify the accreditor for higher education institutions that receive federal student aid dollars. The analysis only includes an institution’s primary accreditor—the one whose approval is necessary to gain access to federal aid, not the one that only accredits a specific program. These data were then matched with student loan default rates from the Office of Federal Student Aid and with information on completions, and borrowing, which colleges reported to the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, or IPEDS.

In assigning an accreditor to each college, the fact that IPEDS and federal student aid data use different identifiers for colleges needed to be addressed. The result is that one college listed by the Office of Federal Student Aid may represent multiple branch campuses in IPEDS. Because accreditation data are tied to the Office of Federal Student Aid data, this analysis consolidated the multiple IPEDS campuses into a single figure. The unavoidable result of this data limitation is that if a branch campus has a different accreditation agency than the main campus, it is still treated as having the same accreditation agency

The analysis uses the number of credentials awarded for every 100 full-time-equivalent students instead of a traditional graduation rate because the graduation rate does not count part-time students or those who transfer in or out of the institution—which are more likely occurrences at the less selective colleges approved by national accreditors. This measure addresses both of these flaws by counting all credentials that a given college awards in a single year and dividing it by a count of all students, including those who attend part time.

In general, a good level of degrees awarded per every 100 full-time-equivalent students is a number close to the percentage that a college is expected to graduate each year due to completion. Consider the following examples: A college that grants four-year bachelor’s degrees where everyone goes full time and graduates should have a rate of 25 degrees per every 100 full-time-equivalent students, since that would mean that one-quarter of its student body graduates each year. At a two-year program with similar characteristics, this rate would be 50 degrees for every 100 full-time-equivalent students.

Results

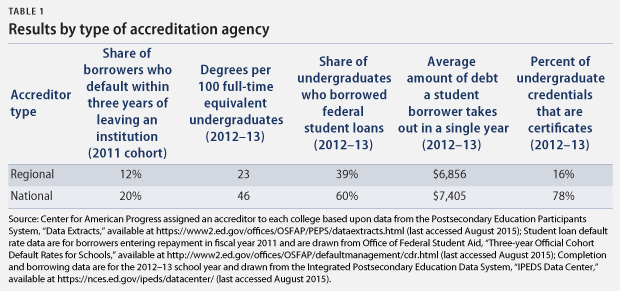

Table 1 shows the differences in default rates, borrowing rates, average loan amounts, and degrees per every 100 full-time-equivalent undergraduate students between regional and national accreditors. As illustrated, the default rate for nationally accredited colleges is substantially higher than the default rate for regional accreditors. To put this number in perspective, if regionally accredited colleges were to default at the same rate as nationally accredited colleges, more than 293,000 additional students would be in default each year than is currently the case.

Similarly, the colleges approved by national accreditors are far more likely to have students who borrow—and borrow more. This is partly due to the fact that students attending nationally accredited colleges are generally lower income; 62 percent of students at nationally accredited institutions receive Pell Grants versus 38 percent of students at regionally accredited institutions. But the borrowing difference should still be concerning because 78 percent of the credentials awarded per year at nationally accredited colleges are certificates. Many of these certificates do not lead to particularly high incomes and provide returns well below the expected results for bachelor’s degrees, which make up 56 percent of the credentials that regionally accredited colleges award each year. Borrowing more for lower-return programs means that students may have more trouble paying off their student loans.

The one measure on which national accreditation agencies appear to perform better is completion. This is due to the mostly shorter programs that nationally accredited colleges offer.

Breaking down the results by accreditation agency reveals that regional accreditors show substantial variation in results, which may be due to geographic differences, such as New England’s larger relative share of private nonprofit colleges with high graduation rates compared to other parts of the country or the West’s larger community college systems. By contrast, the national accreditation agencies all cluster around similar performance levels.

Table 2 shows just how different some of ACICS’ results are when compared with other accreditation agencies. ACICS shows the highest rate of borrowing of any accreditation agency considered: 73 percent. It is 8 percentage points higher than Accrediting Commission of Career Schools and Colleges, or ACCSC, the second largest national accreditor. It also has higher average debt and lower completion figures than any other national accreditor. Only one regional accreditation agency—the Accrediting Commission for Community and Junior Colleges, or ACCJC—approaches ACICS’ default rate. But only 4 percent of students at colleges accredited by ACCJC borrow. And that agency has also been challenged for the quality of its work.

Understanding the scale involved also helps put some of the ACICS results in context. According to CAP analysis, in 2011, approximately 346,000 students at ACICS colleges entered repayment—more borrowers than came from four of the seven regional accreditors individually. Of those borrowers, more than 73,000 ultimately defaulted. This number is nearly one-third higher than the number of defaulters for the Middle States Commission on Higher Education, which had slightly more than 54,000 defaulters despite having 234,000 more borrowers than ACICS.

Another way to interpret the ACICS results is that this accreditor appears to be a strange hybrid of national and regional models. The colleges that it approves offer far more degrees than its national peers, which are focused on certificates. This makes it more like a regional accreditor and partly explains its lower number of degrees per every 100 full-time-equivalent students. At the same time, the fact that its colleges offer higher-level degrees does not appear to result in lower default rates.

As one of the largest national accreditors, ACICS is responsible for giving hundreds of campuses access to billions of dollars in federal student aid. In this role, it has facilitated the growth of several companies with problematic histories, including Corinthian Colleges and the currently embattled ITT Technical Institute.

In a follow-up response to his testimony, ACICS Executive Director Gray noted that “the primary role of ACICS is to assure quality and promote excellence.” It looks like the agency and its national accreditation peers have more work to do to make that role a reality.

Conclusion

Accreditation signals to students that they can expect a certain level of quality in their higher education. Its link to federal aid also implies the U.S. Department of Education’s imprimatur—after all, why would a government agency let students borrow at a low-quality college? But if quality is not actually investigated and verified, accreditors risk putting hundreds of thousands of students in extremely precarious situations that allow them to take on federal debt, which has no statute of limitations on collections and is almost impossible to discharge in bankruptcy.

CAP’s analysis strongly suggests that the current accreditation system does an insufficient job of dealing with quality—at least with respect to the intersection between student debt and borrowers’ ability to pay it back when they enter the workforce. Fixing this issue will require addressing several questions, such as which outcomes should be considered when determining quality, who should conduct quality investigations, and what kind of minimum standards need to be in place to ensure quality. These are all major issues that must be decided in order to ensure that the postsecondary system actually provides students the results it promises.

Ben Miller is the Senior Director for Postsecondary Education at the Center for American Progress.