America in the 21st century will look radically different than it did in the 20th century. There are two interesting trends worth noting that will account for at least part of this difference. First, women are now a majority in the workforce, although progress is uneven, with fewer women in leadership positions. Second, the clean energy economy has begun to take off, currently accounting for 2.7 million U.S. jobs—or 2 percent of all employment—and growing.

At the intersection of these two trends is a real urgency to ensure that gender equity is at the forefront as our nation transforms to become more low-carbon, resilient, and sustainable. Placing gender equity as a priority in the clean economy could help rapidly transition our overall workforce, as the clean economy continues to grow at a rapid pace, taking up a larger and larger portion of total jobs within a variety of sectors.

Embedding gender equity into the booming clean energy market does not necessarily require new policy solutions. The fact is that we already know how to create strong, progressive workforce standards and how to put safeguards in place that prevent discrimination in all its forms. But as we think about the gender gap that exists more generally throughout the economy, it is incredibly important that we continue to consider its impact on the sectors within the clean economy.

This way of thinking has two components. First, we need to make sure that the clean economy does not replicate or reinforce gender inequality. Second, the transition to a clean economy will be faster, stronger, and more sustainable if women are participating equally. As these sectors continue their rapid growth, the incorporation of best practices and standards will ensure that the future is much more equitable, sustainable, and vibrant than the economy of yesterday. The clean economy should be considered an opportunity to model the principles of gender parity that we seek to demonstrate in economic development more broadly.

Below, we examine the gender gap in employment before looking at the sectors that are most commonly employing clean economy workers to give some sense of why it is important to apply best practices and undo some of the damage inflicted by the chronic under-representation of women.

Looking at the gender gap and implications for the clean economy

Hard data on the participation rate of women in the clean energy economy is hard to come by. The best studies on calculating jobs in the clean energy economy—or “green goods and services”—do not disaggregate male and female employment. But as the global Clean Energy Ministerial noted when launching its initiative to involve women more in clean energy:

There is a well-documented gender gap in the clean energy professions, as well as in the broader science, technology, engineering, and mathematics, or “STEM”-related fields. Women in the United States hold only 27 percent of science and engineering jobs, and that number falls to 21 percent when limited to business and industry.

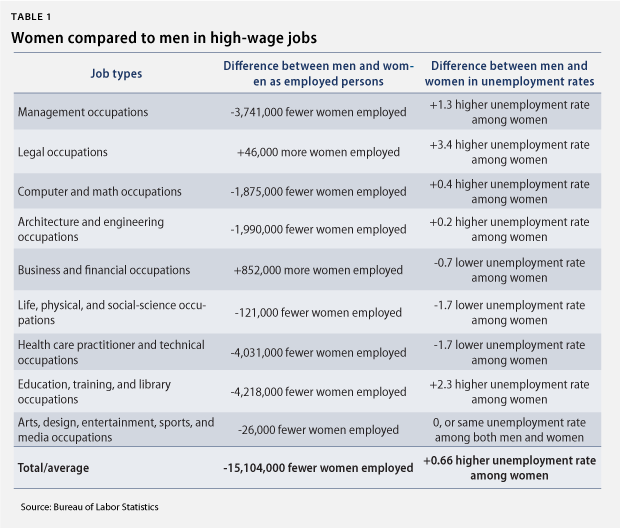

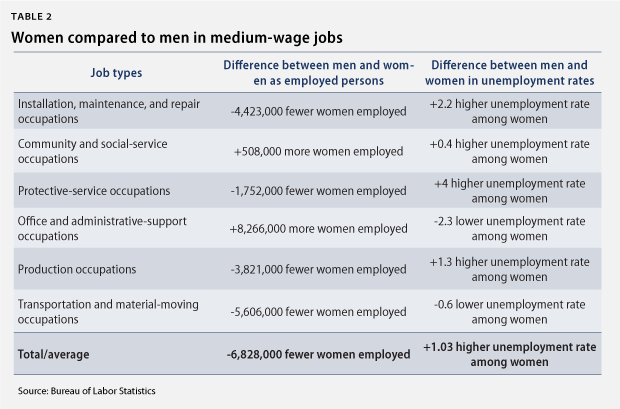

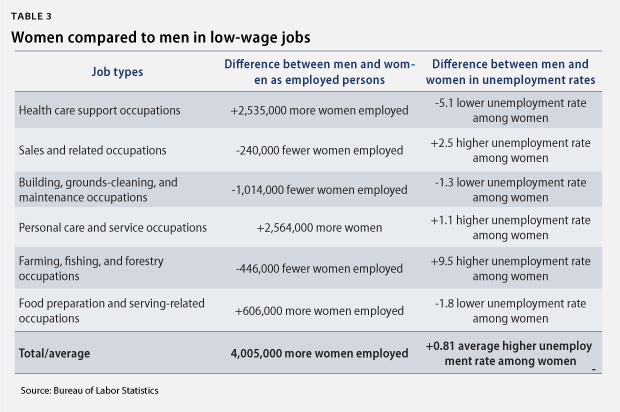

To hash out these claims in more detail, we can look at data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics for overall employment and unemployment trends by sex in different occupations. This will give some sense of the gender distribution in the overall U.S. economy. For comparative purposes, we only examined sectors that had “clean economy” components, as described in the Brookings Institution’s “Sizing the Clean Economy.”

Here are some conclusions culled from the Brookings’ study and the Bureau of Labor Statistics:

- On average, there are fewer women employed in high- and medium-wage jobs.

- Average unemployment rates for women are higher across all wage classes.

- Even in low-wage jobs—where more women than men are employed—the average unemployment rate for women is higher. This means that although more women are employed in low-wage sectors, a higher percentage of them are also still seeking work.

- Some individual sectors where higher numbers of women than men are employed—such as “legal,” “community and social service,” and “personal care and service”—still have higher unemployment rates for women.

- This shows a broader trend wherein women are not only categorically under-represented but are also having a harder time finding work.

Before diving into depth about the implications of these numbers for the clean economy, there is an important caveat: Since this dataset involves overall occupations and not just the clean economy portion of those occupations, these numbers do not conclusively determine female under-representation. It is possible that the clean energy subset of each of these occupations is entirely composed of women or has a higher percentage of women than the overall occupation. But the problem is this: If the clean economy portions of these sectors follow the trends displayed in the overall dataset, women will continue to be under-represented. The Bureau of Labor Statistics should strongly consider disaggregating their study of green jobs by gender in order to track progress on that front.

The good news is that because clean economy occupations are growing at such a significant rate, there is inherent potential for a huge turnaround in these negative trends. As the transition to a low-carbon economy continues, the percentage of these occupations and sectors that are not classified as part of the “clean economy” will grow smaller and smaller, and portion classified as part of the clean economy will grow larger and larger. If best practices and workforce standards are put in place to include more women in the clean economy workforce, the overall trends within all occupations where women are under-represented could reverse themselves, ensuring that our nation would be stronger for it.

Guaranteeing the role of women in the clean economy

There are many good reasons that women should be involved in clean energy. Let’s look at three of the key reasons.

First and foremost, it is abysmal that any demographic that comprises more than 50 percent of our population would not approach nearly that rate of participation in a policy area of such critical import to the planet. Women, similar to men, are facing the devastating impacts of climate change on their families and communities and therefore must be central to any solutions we employ if those solutions are to be viable. Women, similar to men, will have to adjust their living patterns to be more sustainable and adaptive. Women, similar to men, will have unique ideas and voices in the patchwork of solutions that are needed to address climate change.

Second, in many developing countries, women are disproportionately harmed by the lack of energy access due to the societal customs and norms of those communities. Women’s voices in crafting solutions that can lift these groups out of poverty are an essential element in reversing some of the damage done by historical patriarchal approaches to policymaking. Because women are disproportionately affected, they are also a market for equitable solutions. Women have the power as consumers in the clean energy economy, and they should be empowered to craft solutions and make decisions about how best to employ these solutions.

Finally, including women more significantly in clean economy occupations will increase both growth and productivity in those jobs. Reducing the barriers to female participation in the overall workforce—and in the clean economy sector specifically—would increase gross domestic product, or GDP, by up to 9 percent. Eliminating discrimination could increase productivity per worker by 25 percent to 40 percent.

America cannot, and should not, miss the opportunity to embrace equity as a core principle in clean, sustainable economic growth. Ensuring that women are equal partners in all aspects of the burgeoning clean economy will guarantee that the nation’s transition to it will take hold faster and that its benefits will be more widely felt and sustainable.

Adam James is a Research Assistant for Energy Policy at the Center for American Progress.