On March 31, the U.S. Department of Education released for the first time a list of postsecondary institutions that are subject to oversight because of concerns related to their administrative management or financial position. This distinction—called heightened cash monitoring—exists to ensure that federal student aid funds have proper oversight. Making this information public will increase “transparency and accountability” across America’s higher-education system. It will also help students, families, and consumer advocates evaluate whether an institution has a reasonable chance of serving students well and fostering academic success.

Upon releasing this list, the U.S. Department of Education sought to put the information in context. Under Secretary of Education Ted Mitchell explained:

Heightened Cash Monitoring is not necessarily a red flag to students and taxpayers, but it can serve as a caution light. It means we are watching these institutions more closely to ensure that institutions are using federal student aid in a way that is accountable to both students and taxpayers.

In total, 544 institutions were listed under heightened cash monitoring as of March 1, 2015. The majority, 323, were for-profit colleges, ranging from small beauty schools to campuses operated by large, publicly traded companies. A significant number, 74, were public colleges, including community colleges, while 115 were private, nonprofit colleges. The department also included 32 foreign colleges under heightened cash monitoring. More than 7,000 colleges and career-training centers participate in federal student aid programs. The relatively small share subject to oversight appears to convey an acceptable level of risk at institutions: There are clear reasons for being subject to oversight and oversight is not so widespread that it becomes meaningless.

The U.S. Department of Education’s list provided much-needed transparency by revealing the institutions that are subject to heightened cash monitoring. An important question remains, however: What do we know about student enrollment at institutions in need of additional oversight?

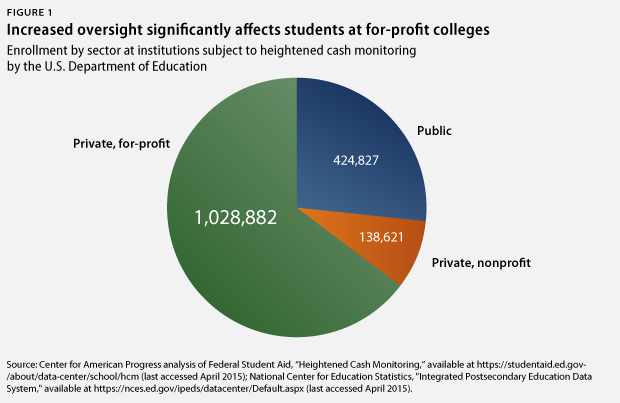

An analysis of enrollment figures reported to the U.S. Department of Education found that during the 2012-13 school year—the most recent period for which data are available—a total 1.6 million students attended a college or institution that is currently subject to the department’s additional oversight. More than 1 million of those students—64.5 percent of the total—attended for-profit colleges. Students who attended public colleges made up 26.7 percent of the total, while students who attended private, nonprofit colleges accounted for the remaining 8.7 percent.

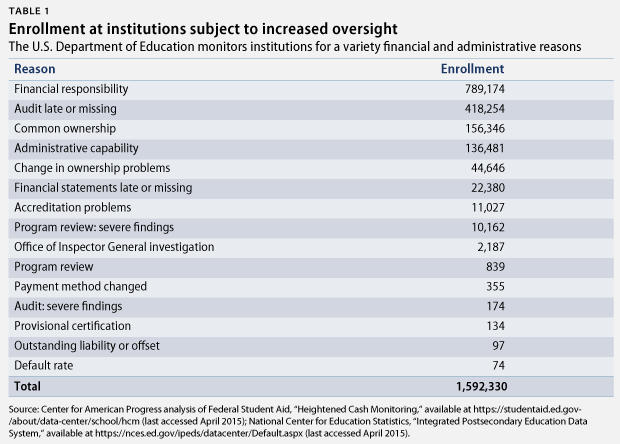

The U.S. Department of Education can place colleges under heightened cash monitoring for a variety of financial or federal compliance issues. Importantly, the department qualifies the inclusion of an institution on its heightened cash monitoring list by noting that some of these reasons “may be serious and others … may be less troublesome.” Because the department’s disclosure contains a list of the reasons why each institution was subject to oversight, it is possible to see how many students attended institutions being monitored for various reasons.

Concern related to an institution’s financial responsibility was the most common reason for increased oversight, affecting 789,174 students. The U.S. Department of Education determines financial responsibility based on a composite score—reported by an independent auditor—about an institution’s financial position. In 2012-13, 418,254 students attended an institution with an annual audit that was late or missing, a less severe warning and the second-most common reason for heightened cash monitoring. The third-most common reason—concern related to common ownership of campuses—applied almost exclusively to the 156,346 students enrolled at institutions operated by Corinthian Colleges Inc., a large, publicly traded for-profit education company that declared bankruptcy last year. The common ownership monitoring applies to all campuses when problems are identified at some schools owned by the same entity.

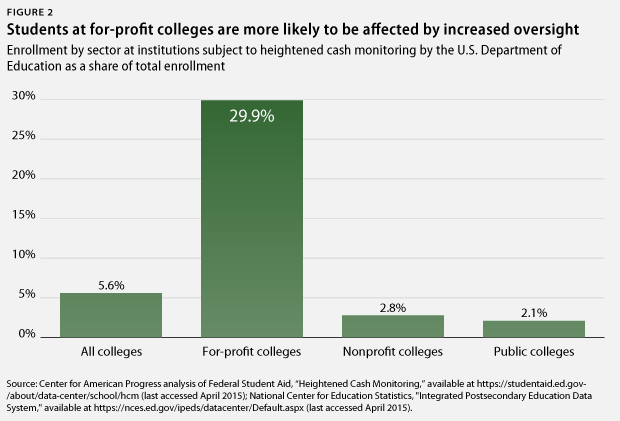

Notably, this enrollment analysis demonstrates that students who attend for-profit colleges are far more likely to go to a school under increased oversight than students who attend public or private, nonprofit colleges. During the 2012-13 school year, 29.9 percent of students who went to for-profit colleges attended an institution that is currently subject to heightened cash monitoring. Overall, just 5.6 percent of students attended an institution that was subject to oversight, while 2.1 percent of students at public colleges and 2.8 percent of students at private, nonprofit colleges attended an institution that was subject to oversight.

Among students who attend institutions subject to additional oversight, the concentration of enrollment in for-profit colleges—whose practices have raised questions about the value they provide to students and taxpayers—is worrisome. Last fall, the Obama administration issued a gainful employment rule to establish standards for career training programs—the majority of which are operated by for-profit colleges—in order to ensure students are not required to take on too much debt while pursuing their education. Meanwhile, an investigation by the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions Committee examined the taxpayer investment in these colleges and found that more than half of the students who enrolled ultimately left their program without obtaining a degree or diploma. Indeed, the for-profit college industry has a troubling track record: Some institutions have taken advantage of students by promising a smooth path to post-graduation employment but instead leave them worse off, saddled with debt and no job prospects.

The U.S. Department of Education’s decision to publicly release its list of colleges currently under increased oversight for the first time was driven, in part, by concern over the surprise closing of colleges, an event that disrupts students’ educations and imperils their futures. When Corinthian Colleges Inc. declared bankruptcy last year, it had been subject to heightened cash monitoring by the department because it had “continually failed to address concerns about its practices.” Given the negative impact that abusive practices and abrupt closures can have on students, it is important that the Department of Education continues to be transparent about its concerns related to institutions that participate in the federal student aid programs.

The modern U.S. economy demands that workers possess knowledge and skills learned while pursing education beyond high school. For students to have the best chance for success, they must have clear information about the quality and stability of the colleges they might attend. If there is a “caution light” for students when selecting a college, they should be able to see it clearly.

Methodology

The list released by the U.S. Department of Education is organized by an institution’s Office of Postsecondary Education identification number, or OPEID, which is assigned by Federal Student Aid to track the flow of federal student loans and grants. Separately, institutions report enrollment information by campus to the Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System, or IPEDS, a database operated by the Department of Education’s National Center for Education Statistics. An OPEID can include multiple campuses listed individually in IPEDS. To calculate the correct enrollment figure, the information was collected from IPEDS by downloading the total enrollment for the most recent school year available—2012-13—and the OPEID associated with each campus. This analysis used a 12-month unduplicated headcount to capture all students enrolled during the school year. Enrollment data were then collated and subtotaled by OPEID to determine how many students attend the colleges under heightened cash monitoring. The majority of foreign institutions listed on heightened cash monitoring are not listed in the U.S. Department of Education IPEDS database that collects enrollment figures. Therefore, enrollment information for that sector is not available. The absence of these figures does not substantially affect this analysis because most of the students attending those institutions are not American citizens.

Elizabeth Baylor is the Associate Director for Postsecondary Education at the Center for American Progress.