In many cities across America, it’s not just schools that are failing—it’s the entire school district as well. Huge numbers—if not the majority—of students throughout these districts are not reading at grade level and lack basic math skills.

This is a problem greater than any one school. In response, some cities have shaken up the way their school districts are run, giving greater control to their mayors and implementing what is called “mayoral control” of schools. School districts are traditionally controlled by a locally elected school board, which makes decisions about how schools are run, including hiring and firing the school superintendent. Mayoral control, however, is a shift in the power structure wherein mayors are given a greater degree of authority over schools. Often, though not always, mayors are given the power to appoint members who will replace some or all members of the elected school board.

The move to mayoral control is one element in the larger discussion about who should run our schools, but it is also a significant and potentially impactful alternative to the traditional structure—and it comes at a time when schools and students are desperate for alternatives.

The Center for American Progress recently released a new report analyzing the impact of mayoral control. The report, titled “Mayoral Governance and Student Achievement: How Mayor-led Districts Are Improving School and Student Performance” by Kenneth K. Wong and Francis X. Shen, looks at the impact of mayoral control on resource management and student achievement in 11 different school districts across the country.

Based on CAP’s new report, here are the top five things to know about mayoral control of schools:

It’s been done all across the country in cities of all sizes

Some variation of mayoral control has been implemented in a geographically diverse range of urban cities, from New York City to Indianapolis to Los Angeles and many places in between. These cities have different student populations, structures, and histories, but empowering the mayor to make at least some of the decisions about schools has been tried in all of them.

Though the adoption of mayoral control in big cities such as New York City or Philadelphia may get the most press attention, being “big” isn’t a precursor to pursuing mayoral control. Mayors in small cities such as Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, and mid-sized ones such as New Haven, Connecticut, have also been given greater authority to govern their school districts. Mayoral control is an approach that many cities can try.

Mayoral control comes in many shapes and sizes

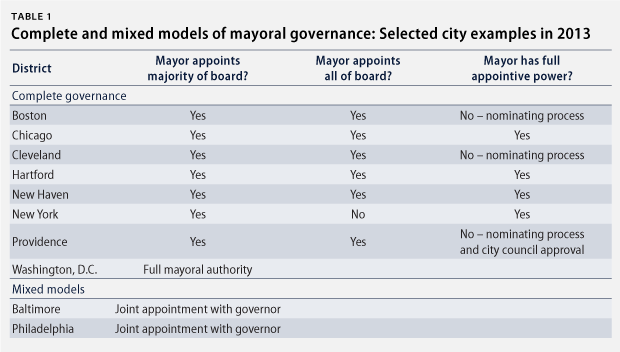

Despite what the name might imply, there is no “one and only” type of mayoral control. Different cities have taken different approaches, and new formats are still being invented. There is a lot of room for variation depending on local priorities, decisions, cultures, and any number of other factors. The term “mayoral control” simply signifies that the mayor has more power now than he or she did before. What that means in practice is up to the city or state in question.

There are, however, a few common forms or degrees of control. Some cities have given their mayor the power to appoint the entire school board and the CEO, or superintendent, of the school district. Examples of where this has happened include Washington, D.C., and Chicago. In New York City the mayor appoints the CEO and the majority—though not the entirety—of the board. Together, these three cities have “very high” degrees of mayoral control. Cities that empower the mayor to appoint at least the majority of the school board, but give the boards the authority to appoint the CEOs, fall into the high degree of control classification. This category—also the most common—includes Boston, Massachusetts; Cleveland, Ohio; Hartford, Connecticut; New Haven, Connecticut; Providence, Rhode Island; Trenton, New Jersey; and Yonkers, New York. Even within this category, there is variation: The mayors of Boston, Cleveland, and Providence must choose their board appointees from a list of nominees.

In Baltimore and Philadelphia the mayor and governor jointly appoint members to the school board, demonstrating a “moderate” degree of mayoral control. In Los Angeles the mayor manages a handful of feeder elementary and high schools, but the large majority of schools are still under the control of the elected school board. Similarly, in Indianapolis the mayor’s office authorizes and monitors charter schools in the city, but the school board is otherwise in charge. In Rhode Island mayors have recently been given the power to sponsor charter schools that are then overseen by a specific nonprofit organization: the Rhode Island Mayoral Academies.

The point is, there is no one-size-fits-all version of mayoral control, and cities interested in giving greater authority to their mayors can likely find a version that works for them.

Mayor-led districts may use resources more strategically

There is evidence that districts operating under mayoral control may spend their money differently, more strategically, and with a greater focus on the classroom than districts governed by elected boards. For starters, mayoral-led districts have more resources per student overall than similar city districts, though the cause of this is hard to identify definitively. On average, districts under mayoral control also focus on teachers: A greater percentage of their total staff is teachers, producing lower student-to-teacher ratios. Relative to the largest city districts, mayor-led districts have less central office staff and administrators as a percent of their total staff. This prioritization on teaching and learning might be an important factor in contributing to higher student achievement, as discussed below.

Mayor-controlled districts have seen increases in student achievement

Although other factors are important, the ultimate measure of any change in our education system is whether it improves student learning and achievement. In Boston, Chicago, New York City, Washington, D.C., and other cities, mayoral control is associated with just that. Students saw improvements—in some cases significant improvements—on both state assessments and on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, a test administered nationally to fourth and eighth graders. Looking at the National Assessment of Educational Progress scores, for example, the percentage of Bostonian fourth graders proficient in math went from 12 percent to 33 percent—an increase of 21 percentage points—under mayoral control. Similarly, the percentage of fourth graders in Washington, D.C. that were proficient in reading went from 10 percent to 20 percent—an increase of 10 percentage points—after the city moved to mayoral control.

Some of the most notable gains in achievement were among minority and lower-income students. For Latino fourth graders in Boston, for example, the percentage who were proficient in reading rose from 12 percent to 23 percent—an increase of 11 percentage points—under mayoral control. Black students in Washington, D.C., and New York City saw gains among fourth graders in math proficiency of 8 percent and 7 percent, respectively. In Chicago the percentage of students eligible for free or reduced-price lunches that were proficient in fourth grade math increased from 8 percent to 16 percent—a gain of 8 percent. To give you a sense of what this means, there are roughly 22,000 fourth graders in Chicago eligible for free or reduced-price lunches, meaning that an increase in proficiency of 8 percentage points would result in 1,700 more students being proficient in math. That is a significant jump.

It doesn’t work everywhere, but it can be a catalyst for reform

Mayoral control was less successful in cities such as Cleveland, Ohio, and Yonkers, New York. In Cleveland student achievement on the National Assessment of Educational Progress improved just slightly, if at all, and the gap between the average among large cities and the district’s achievement widened—not narrowed—for almost every grade, subject, and student population. This is exactly the opposite of closing the achievement gap. To be clear, it’s impossible to know why achievement stagnated in these cities, and certainly numerous factors other than mayoral control are involved. But it is important to recognize that mayoral control may not be the right solution for all districts.

In the right cases, however, mayoral control can be a catalyst for reform. Mayoral control is most effective when the mayor is ready, equipped, and dedicated to providing strong educational leadership and to setting a clear and cohesive vision for educational improvement and innovation. A great example of this potential for reform is the much-acclaimed district-teacher contract negotiations in New Haven, Connecticut. Working together on a collaborative effort, the district leadership led by Mayor John DeStefano and the New Haven Teachers Union reached an agreement to adopt a new teacher evaluation system that incorporates student performance, to implement new school turnaround efforts, and to increase teacher salaries. This agreement moved New Haven to the forefront of the educational improvement efforts—something all districts should aspire to achieve.

Conclusion

Mayoral control of schools can be effective. Mayor-controlled districts have seen improved student achievement across all subjects and student groups. Moving to a mayor-led district can also help spur innovation and advancement. In cities with lagging student achievement, getting more engagement from mayors or increasing their authority over schools could be part of the solution. But voters and policymakers should be sure to design a variation of mayoral control that works for their city and consider the possibility that a different “shake up” strategy might be a better fit.

Juliana Herman is an Education Policy Analyst at the Center for American Progress.