Central America’s Northern Triangle region—made up of El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala—has gained notoriety in recent years for its extreme levels of organized crime, gang violence, and poverty. As these problems have intensified, the number of people fleeing from the Northern Triangle to other countries has also skyrocketed. While lower than the surge in summer 2014, the uptick in the number of unaccompanied children and families arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border in the latter months of 2015 is still historically high and serves as a stark reminder of the region’s worsening conditions.

The most dangerous countries in the Western Hemisphere

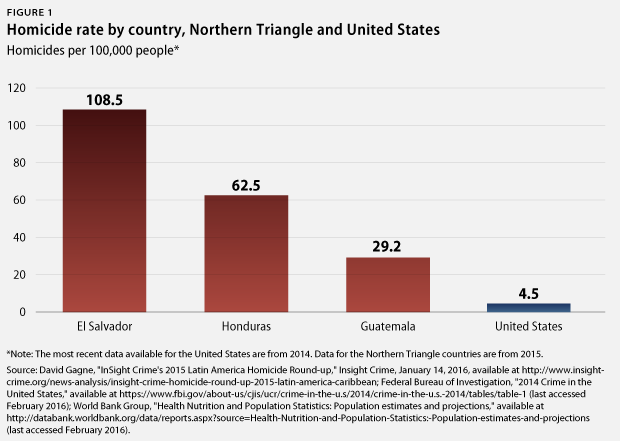

According to InSight Crime, El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala were among the five most dangerous countries in the Western Hemisphere in 2015. While Honduras’ homicide rate has decreased over the past few years, El Salvador’s homicide rate has deteriorated significantly—making the country more than 24 times as dangerous than the United States. (see Figure 1)

Gangs are the drivers of much of the violence occurring in the Northern Triangle. In 2012, the U.S. Department of State estimated that there were about 85,000 gang members spread throughout the region, with the greatest number residing in Guatemala. Extortion from criminal organizations was also widespread. According to data compiled in 2015 by La Prensa, citizens of El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala pay more than $651 million annually to criminal groups who threaten them with death and violence if they fail to pay extortion fees. Extortion is a lucrative source of income for gangs, and targets for extortion can include anyone from vulnerable business owners who seem to be doing well to bus drivers.

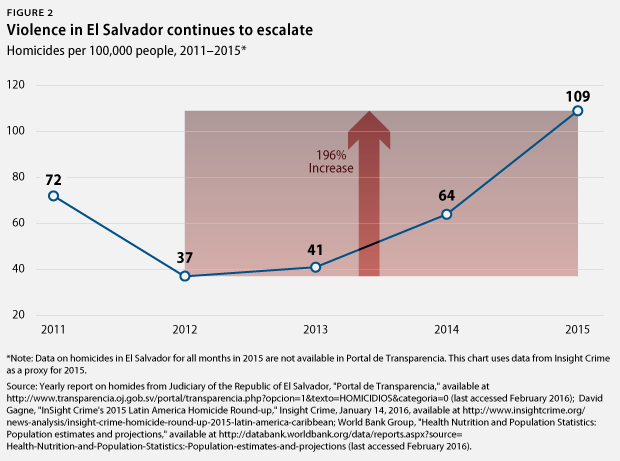

Violence in El Salvador escalated in 2015

In 2015, the murder rate in El Salvador jumped nearly 200 percent from its rate in 2012. According to the National Forensics Institute, August 2015 was the most deadly month in El Salvador since the civil war ended in 1992, with an average of one murder occurring every hour.

The increase in violence in El Salvador since 2014 was mainly due to the unraveling of the 2012 truce between two of the country’s main gangs—Mara Salvatrucha, or MS-13, and Barrio 18, both of which are known as the maras. As a result, it has become increasingly common to hear stories about people of all ages—including young children—fleeing El Salvador’s gang-controlled cities under the threat of “murder, extortion, kidnap and rape.”

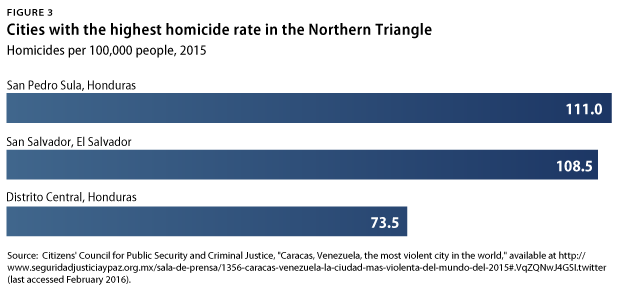

Cities in the Northern Triangle are among the most dangerous in the world

San Pedro Sula, Honduras—which was considered the “murder capital of the world” from 2011 to 2013—had a homicide rate of 111 per every 100,000 people in 2015, making it the second most dangerous city in the world after Caracas, Venezuela. Approximately 97 percent of the murders in San Pedro Sula were unsolved as a result of limited resources; inadequate training of local police forces; and corruption. San Salvador, the capital of El Salvador, was the third most violent city in the world in 2015, with a homicide rate of 109 per every 100,000 people—an 80 percent increase from 2014.

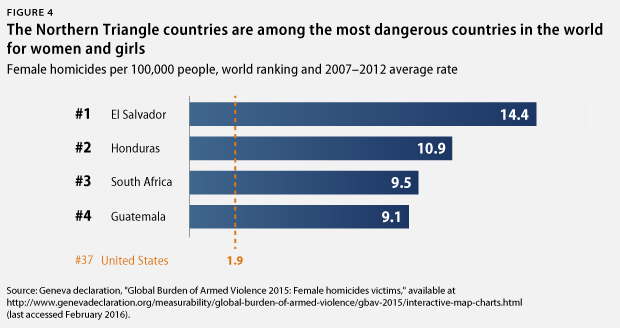

No safety for women and girls

El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala are also among the top five countries in the world with the worst female homicide rates. Last year, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, or UNHCR, released a report revealing that women who fled the Northern Triangle and Mexico for the United States described “being raped, assaulted, extorted, and threatened by members of criminal armed groups, including gangs and drug cartels.” The U.S. Department of State reports that the Guatemalan conviction rate for “femicide”—or killings of women and girls—was around only 1 to 2 percent.

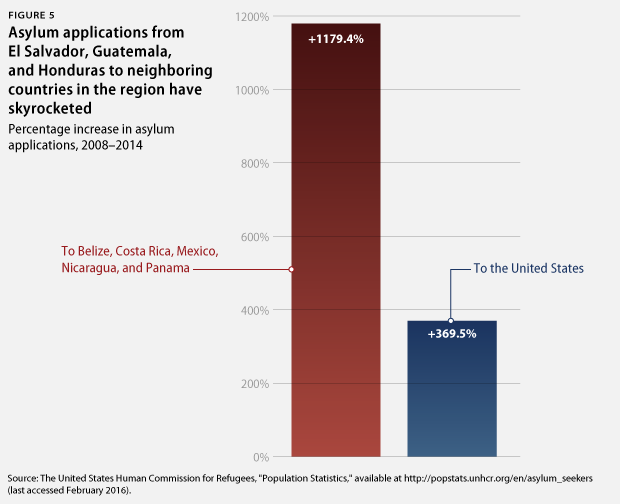

Asylum applications to neighboring countries have skyrocketed

The effect of this extreme level of violence is the escalation in the number of people fleeing the region. Data compiled by the UNHCR show that the number of Salvadorans, Hondurans, and Guatemalans who request asylum in Belize, Costa Rica, Mexico, Nicaragua, and Panama increased by a staggering 1,179 percent from 2008 to 2014, while asylum requests increased by 370 percent for the United States over the same time period. A jointly written report from the Northern Triangle countries states that as much as 9 percent of each countries’ total population has emigrated in recent years.

Of these individuals, many who come to the United States qualify for protection. In fiscal year 2015, for example, U.S. asylum officers interviewed 16,077 women from the Northern Triangle and Mexico and found that 82 percent, or 13,116 women, had a “credible fear of persecution or torture”—the first step in establishing an asylum claim. Many of the children and families who request asylum and are able to obtain legal counsel can then obtain relief and permission to remain in the country.

Conclusion

Given the staggering levels of violence in the Northern Triangle region, the United States must work with these countries and the UNHCR to find a holistic approach to address the root causes of emigration; provide opportunities for people to request and make full and fair claims for protection; and have proper screening procedures for those who arrive at the U.S. border seeking asylum. The $750 million that Congress recently appropriated to help El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala improve security, mitigate poverty, and strengthen their governments is a good start toward tackling the root causes of violence and poverty. In the meantime, the United States must stay true to its commitments to protect desperate people—especially women and children—who are pursuing security and freedom.

Silva Mathema is a Senior Policy Analyst on the Immigration Policy team at the Center for American Progress.