On Friday, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics will release the employment report for the month of March. This month’s new data will be another important indicator of whether the major gains we’ve seen in employment are enough to boost wages in the labor market. The public and politicians are clearly impatient for wage growth to happen. Earlier this week, California Gov. Jerry Brown (D) and state legislators reached a deal to increase the state’s minimum wage to $15 per hour by 2022, an important step toward raising incomes in the most populous U.S. state. As the national conversation turns away from the deep recession and impressive recovery toward wage growth, hopes are high for improving quality of life for lower- and middle-class families.

The national unemployment rate for the month of February remained at 4.9 percent, a record low in this recovery and less than half its peak of 10 percent in October 2009. In the past year alone, the labor market has seen robust job growth at an average rate of about 226,000 new jobs per month. Even so, wages have been lagging behind growth in jobs more than usual after our deep recession, and the number of long-term unemployed workers has stayed mostly steady since last summer. After the February employment release, word got out that Federal Reserve officials would raise interest rates only two times this year instead of the planned four. This change of plans signals the Fed’s wariness to hinder an economy growing the way ours has been and an important openness to looking at inflation and labor market data that signal our economy can do better.

Here’s a quick look at the labor market trends to watch for as we approach the release of the upcoming report.

Job growth has picked up, but the depth of the Great Recession means that employment growth since before the recession still lags behind historical standards

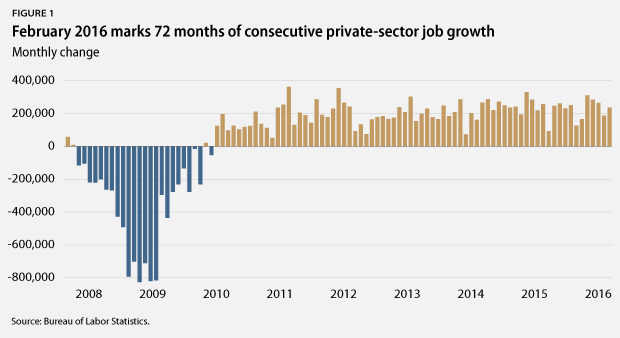

There were 12.5 million more jobs in February 2016 than in June 2009, when the recession officially ended. During this same time period, the private sector added 13.1 million jobs. In February 2016 alone, the private sector added 230,000 jobs to the economy, marking 72 months of consecutive private sector job growth.

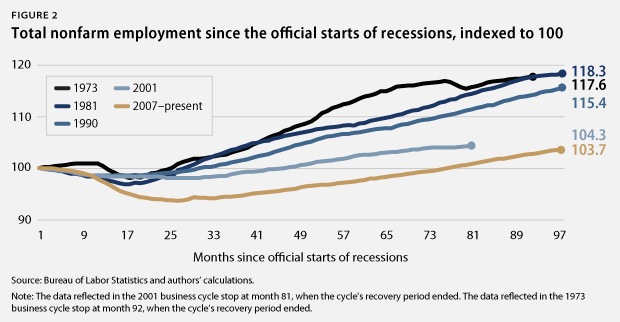

Overall, job growth has been particularly robust over the past year, with average growth of 228,000 jobs per month since December 2015. However, job growth in this recovery has not been especially robust relative to previous economic expansions. During the economic expansion of the 1990s, for example, the economy added at least 250,000 jobs per month 49 times. During the current expansion, which has now lasted more than half as long, we have seen 21 months of job growth greater than 250,000, which includes abnormal hiring involved with conducting the decennial census. Combined with the extraordinary job losses that the U.S. economy sustained during the recession, the pace of both job and wage growth suggests that there is much more slack in the labor market than the headline unemployment rate may indicate.

Headline unemployment hits a record low, but other economic measures show room for improvement

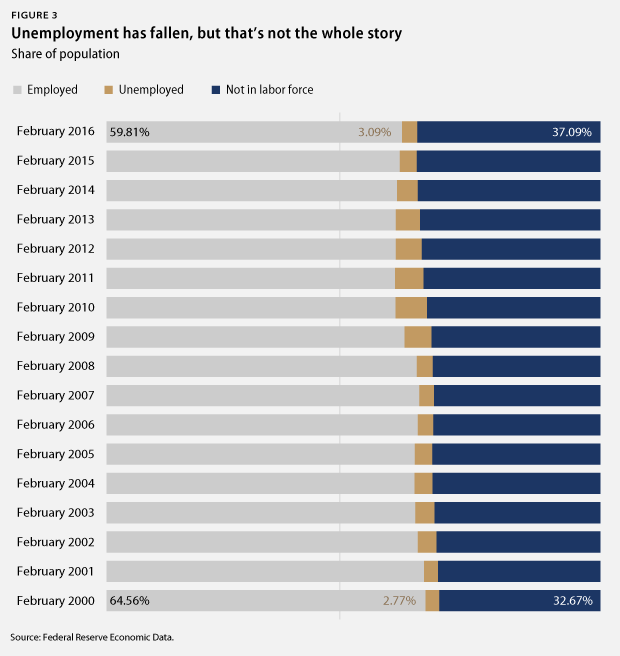

February 2016 marked the 17th consecutive month that the headline unemployment rate—otherwise known as U-3—was less than 6 percent, as it stayed flat at January’s 4.9 percent rate. This is a record low since the end of the Great Recession in June 2009. While this does mark significant progress in the recovery, it is important to remember that there are broader measures of unemployment that paint a clearer picture of the employment situation.

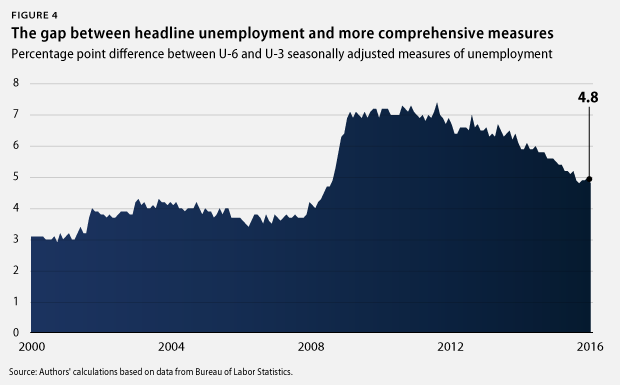

U-3, the typical measure, is pretty restrictive, as it counts the percentage of people who are actively looking for work but cannot find it. U-3 does not, however, capture the millions of people who want jobs but have given up looking or who would like full-time work but cannot find it in this economy. Perhaps the most comprehensive unemployment measure, called U-6, alleviates this problem by including marginally attached workers—those who have recently looked for work but are not currently looking—and those working part time but who would prefer full-time work. U-6 is always higher than U-3, but the gap grew much larger than usual during the recession and has remained above or near prerecession records over the course of the recovery.

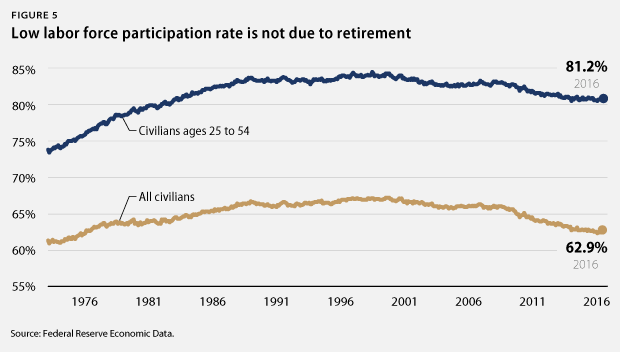

Another important measure is the labor force participation rate. When the economy is doing well, more people typically enter the labor market because there are more jobs available. So one should expect the labor force participation rate to be increasing in the aftermath of the recession. However, it hasn’t been. Rather, it has declined since the recession’s end and is as low today as it was in the late 1970s, when women entering the workforce became the norm. Even with three solid months of gains, labor force participation is still low by historical standards, which suggests that there is considerable room for job gains going forward.

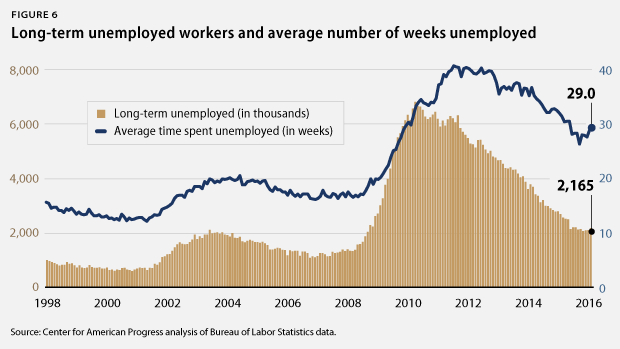

Long-term unemployment is down sharply but still remains high

In November 2015, long-term unemployment was at a record low since the end of the recession, hitting less than one-third of its postrecession peak. Today, while down sharply, the number of long-term unemployed people is still higher than its highest prerecession level in 2003. There are still more than 2 million Americans who have been unemployed for more than half a year and are still actively searching for work. 27.7 percent of all unemployed workers fall into this long-term unemployed category. The average length of time someone has spent unemployed is about seven months, well above what it was right before the recession.

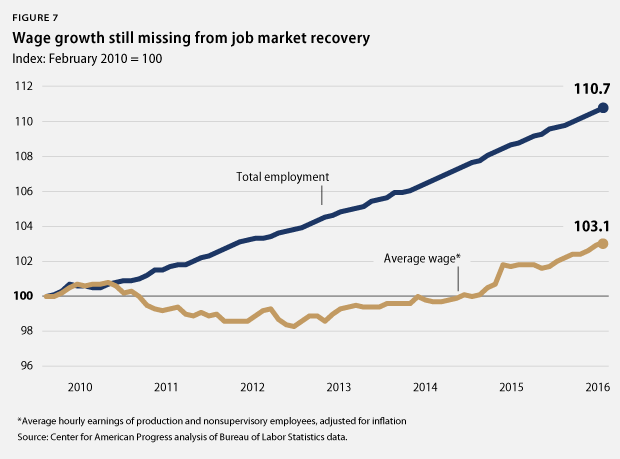

Americans are still waiting for a raise. Due to the slack caused by slow employment growth, real wage growth remains essentially stagnant. As depicted above, the labor market has experienced significant gains in employment in this recovery, but growth remains slow by historical standards. Slow employment growth has caused slack in the labor market, thereby leading to stagnation in real wage growth. Continuing the trend of the past 30 years, while corporate profit growth has been strong, middle-class workers continue to grapple with the challenges of rising costs and slow wage growth.

Conclusion

While meaningful progress has been made since the end of the Great Recession, it is important to remember that many Americans are still suffering from its effects. It’s not exactly a secret that the Great Recession was much deeper than any other recession in recent memory, and slack in this recovery still remains. Identifying the exact cause of the considerable slack in the labor market is a challenge—maybe it’s the underperformance of the housing sector or of Congress—but the slack in the economy is real. Many people who want full-time work are still missing from the labor force or are working fewer hours than they would like. These workers are the key to raising the nation’s potential economic output and future gross domestic product, or GDP. Beyond employment gains, wages had stalled before the recession and they have yet to accelerate in the recovery.

This is the real challenge that the Federal Reserve faces: It’s hard to predict what wage and price growth will do as the economy picks up steam, but so far, workers seem to be slowly coming off the sidelines, raising employment but tempering wage growth. However, this cannot happen forever. As the economy picks up speed, the Fed is right to let interest rates stay close to zero to help as many Americans as possible get back to work. Pulling the long-term unemployment rate down and raising wages are the next challenges facing the Fed, and treading lightly seems to be its plan of action for the immediate future. It’s also what the data says the agency should do.

Michael Madowitz is an Economist at the Center for American Progress. Shiv Rawal is a Research Assistant for Housing Policy at the Center. Juliana Vigorito is a Special Assistant for the Economic Policy team at the Center.