American workers and their families no longer look the way they did in the 1960s. Women’s participation in the labor force has been steadily growing over time, and women now make up about half of all workers. More working women is partially the result of personal choices and partially the result of economics. Consider that among families with children, only those with both parents working have seen real income growth in the past 30 years.

Yet in spite of the fact that our lives have changed so dramatically, the United States remains the only advanced economy that does not guarantee workers the right to paid time off when they need to provide care to their families. Three key facts tell the story.

Women now make up approximately half (49.3 percent as of September 2012) of all workers on U.S. payrolls, compared to making up only one-third of workers in 1967.

Mothers are now often the family breadwinner. In 2010, in nearly two-thirds of families (63.9 percent), a mother was the breadwinner—bringing home as much or more than her husband or a single working mother—or a co-breadwinner, bringing home at least a quarter of the family’s earnings. (see Figure 1)

As a result, most children are growing up in a family without a full-time, stay-at-home caregiver. In 2011, among families with children, 40 percent were headed by two working parents, and another one in three (31.9 percent) were headed by a single parent. Only about one in five children today (20.7 percent) live in a family with a traditional male breadwinner/female homemaker, compared to nearly half (44.7 percent) a generation ago.

Unfortunately, unlike our industrialized competitors, the institutions around us—schools, churches, workplaces, and government—have not adjusted at the same pace to reflect the realities of how our families work and live today. (see Table 1) The negative consequences resulting from the lack of a federal paid leave program are felt across a variety of domains, from individual homes to our economy writ large.

To address this, the Center for American Progress proposes Congress enact and the president sign Social Security Cares, legislation first outlined in our report “Helping Breadwinners When It Can’t Wait” and included in the Center’s proposal to modernize Social Security, “Building It Up, Not Tearing It Down.” This issue brief details the benefits of Social Security Cares.

Social Security Cares: The basics

Our proposal builds on the dynamic history of Social Security reform to meet the changing needs of the American workforce alongside further developing themes in the Family and Medical Leave Act as well as recent state efforts to ensure that it is crafted to include all workers who need access to such benefits. The proposed program builds on the kind of qualifying conditions recognized under the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 to help workers who need time out of the labor force provide care for a seriously ill family member, recover from their own illness, or bond with and care for a new child.

The implementation of Social Security Cares would have far-reaching positive consequences. Specifically:

- Social Security Cares was conceived to address the needs of our increasingly diverse workforce. It would give new parents; those with family caregiving responsibilities, including family caregivers to the elderly, one of the fastest growing segments of the population; and workers who experience a serious illness or accident time for care when they and their families need it most, encouraging healthy recoveries from illnesses both for workers and their loved ones.

- Social Security Cares would increase the number of workers who have access to paid medical and caregiving leave, which will ensure that all workers who pay into the system can receive paid leave when they need it, in addition to helping workers better manage their dual responsibilities as workers and caregivers.

- Social Security Cares would increase the labor force participation of caregivers, resulting in greater economic security in their retirement while at the same time helping to shore up the Social Security Trust Fund.

- Social Security Cares would promote greater gender equity and be an important advancement in working to close the wage gap between men and women. It also recognizes, importantly, that men are reporting more work-life conflict than women and they, too, want to be able to spend more time with their families.

- Social Security Cares would do all of this without presenting a significant cost to businesses. In fact, for those organizations that already provide paid family and medical leave out of company coffers, Social Security Cares could result in cost savings.

This modernization of Social Security would tap into traditional American values—that family comes first and that if you work hard and pay into the system, you will be able to access help when you and your family need it.

This core value of the American work ethic is part of the reason why Social Security has one of the highest levels of public support of any targeted government program. More than 60 percent of adults have consistently rated Social Security as one of the most important government programs for the last quarter century. And more than 80 percent of adults believe that everyone who pays into Social Security should be able to receive benefits, reflecting our basic American values regarding the importance of family, fairness, and the reward of hard work.

There is historical precedence for this proposed new program. Social Security has, in fact, evolved over time to serve Americans’ changing needs. The Social Security Act was originally passed in 1935 to provide income security for seniors, but it has grown since then to include Social Security Disability Insurance, benefits for workers who are expected to be out of work due to disability for a year or more (1956); and Supplemental Security Income, a purely need-based income for persons with disabilities (1972).

Social Security has also adapted to shifting demographics over the decades. In 1983 Congress ensured that funds would be available to sustain aging baby boomers by preemptively boosting revenue and adjusting the retirement age. Social Security has also demonstrated it has the capacity to handle claims quickly, through the Compassionate Allowances Initiative and Quick Disability Determinations, programs that expedite the applications of workers whose medical conditions make them more likely to qualify for Social Security Disability Insurance.

There is every reason to be optimistic, therefore, about the implementation of Social Security Cares. The commissioner of the Social Security Administration would establish an Office of Paid Family and Medical Leave within the agency to administer the Social Security Cares program. In this way, the expertise of the Social Security Administration staff would be immediately brought to bear designing and implementing the new law, relying on their experience at setting standards, evaluating applications, and adjudicating disputes.

Social Security Cares: What is it?

Social Security Cares would provide up to 12 weeks of paid leave to qualifying workers experiencing the following life events:

- The birth of a newborn or the arrival of a newly adopted or fostered child

- The serious illness of a spouse, domestic partner, parent, or child

- The worker’s own serious illness that limits his or her ability to work

The Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 already provides unpaid, job-protected leave for these three kinds of events, but only about half of the workforce qualifies for this leave, and many cannot afford to take it because it is unpaid.

Eligibility for Social Security Cares would be calculated using the same employment history criteria as Social Security Disability Insurance. It takes into account a worker’s lifetime employment history, rather than their tenure with a specific employer. And the calculations are age-adjusted, meaning young workers can qualify with fewer years of employment than older workers.

There are several ways that Social Security Cares could be funded. These alternatives are laid out in our reports, “Helping Breadwinners When It Can’t Wait” and “Building It Up, Not Tearing It Down.” Building on the model set out by the two states that have a paid family and medical leave program, California and New Jersey, if the full cost was funded by an increase in payroll taxes, the cost for the average full-time worker earning the median hourly wage of $16.57 would be about $1.33 per week, less than the cost of a cup of coffee from most chain restaurants.

Social Security Cares is a social insurance program, not a social welfare program. Social insurance programs function because all workers pay into the system in order to pool costs and risks. As a result, like with Social Security retirement benefits, it is important that the workers who pay into the system know that the program will be there for them when they need it.

This means that Social Security Cares has much broader coverage than the Family and Medical Leave Act. In order to qualify for leave under the Family Medical Leave Act, a worker must have been employed for at least 12 months and have worked a minimum of 1,250 hours during that time for an employer with at least 50 employees within a 75-mile radius. The job-tenure and employer-size requirements automatically exclude half of all private-sector workers. Young people and people of color are particularly likely to be excluded from taking job-protected FMLA leave.

Social Security Cares will enable workers to help provide care to children, aging baby-boomers, the sick, and people with disabilities

Because most families no longer have a full-time, stay-at-home caregiver, most workers need time off from work to provide care when a new child comes into the family or when an ailing family member needs help. While much of the research and discussion on paid family leave is centered around leave for parents, specifically maternity and paternity leave after the arrival of a new child, babies and children are not the only family members who can need a great deal of care and attention. Everyone has a parent at some point in their life, and illness, accidents, and disabilities are by their very nature unplanned and unforeseen.

Elder care is a growing national issue. It is projected that by 2050 up to 20.2 percent of the American population will be over the age of 65. At present nearly 20 percent of those over the age of 65 need help with the basic activities of daily living. And while the overall proportion of disabled elderly persons has declined, increases in people over the age of 65 have resulted in large numbers of elderly people who need care.

The majority of elderly people with disabilities live in the community, not in nursing homes or care facilities, with family members providing the majority of daily care. In the same way that women are expected to provide the majority of child care, they are also the most likely family members to be enlisted to provide unpaid care to the elderly. As a result, more than two-thirds of the unpaid caregivers for the elderly are women.

Providing care to an elderly family member takes a toll on employment. Both men and women see a reduction in their paid work hours when providing unpaid elder care, but the effect is stronger for women. While men who provide two or more hours of care to their elderly parents per week experienced a 28 percent reduction in their paid employment hours, multiple studies have found that women’s work reduction was more than 40 percent.

Women who live with their elderly parents see the largest dip in their work hours. The majority of this reduction is due to withdrawal from the work force, rather than an actual reduction in hours. In short, for these women, leaving work and moving in with their elderly parents or having their parents move in with them is likely to be the result of their caregiving responsibilities, rather than the reason they elected to be the ones providing care in the first place.

Rather than forcing workers to reduce their hours (if that is even possible with their employer) or leave their job altogether, paid family and medical leave insurance would enable these workers to provide care for those in need while still allowing them to return to work once their parent is in better health.

Adult children of aging parents are not the only ones who often find themselves reducing their work hours to care for a loved one. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services estimates that about 15 percent of U.S. children (11.2 million in total) have special health care needs. This means that more than one in five households with children have at least one child who has special needs. And of those families, 25 percent have had to either cut back their hours or stop working all together in order to provide care for their child.

While Social Security Cares would be of less use to parents whose children have profound, permanent disabilities that require around the clock care, it would help parents whose children may have flare-ups, or periods of time when they require more care than they normally do. About 1.4 million special needs children, for example, missed 11 or more days of school due to illness, and Social Security Cares would allow parents to stay home and care for these kids until they were well enough to return to school, without having to risk losing all of their wages.

Social Security Cares will sharply increase access to paid family and medical leave insurance, especially among the least paid

Two states, California and New Jersey, recognize the need to make paid family leave insurance available to all workers, having put in place such programs over the past decades. The state of Washington also passed paid family leave legislation, but it has yet to be implemented. Workers in other states have no guarantee to paid leave unless their employers voluntarily choose to provide it.

Some workers do have access to paid family and medical leave through their workplaces, but because coverage is a voluntary option for employers, it is often offered as a perk for the highest-paid workers. Overall, slightly less than half of all workers (45.5 percent) report having access to paid parental leave, which could be leave specifically for serious illnesses or when a new child comes into the family or another kind of leave, such as vacation or sick days, which can be used when family leave is necessary.

About a third (32.3 percent) report having access to some form of paid leave that can be used when a child is ill or needs special care. But workers whose average wages are in the lowest 20 percent for their industry are approximately six times less likely to have access to paid parental leave and nearly seven times less likely to have access to paid leave they can use for child care than those in the highest 20 percent.

In 2011 only 37 percent of private-sector workers had short-term disability insurance, which provides income support to workers with a serious illness and, thanks to the Pregnancy Discrimination Act, must cover both pregnancy-related leave as well as medical leave. Coverage rates, however, are uneven. Coverage is lower for part-time and lower-wage workers; women of color are less likely to have access to paid maternity leave; and the odds of having coverage decrease for all women the younger they are or the less education they have.

Men’s access to parental leave has increased over time, though still less than half (44.5 percent) of male workers have even a single day of paid paternity leave available through their employer. And as with women, men of color, younger men, and men with less education are all less likely to have access to paid paternity leave. Even among Fortune 100 companies—9 out of 10 of which offered some form of paid leave that could be taken after the arrival of a new baby—only a third offered paid paternity leave to men.

As a result, workers are often left with few options when they need time away from work to provide care to their families or because they have a work-limiting illness. For most, the only options are to cobble together whatever forms of leave they may already have, such as vacation or sick leave—each of which only about 60 percent of workers have access to in the first place and which is often inadequate—or quit. Unless a worker is lucky enough to have an employer that voluntarily offers paid leave, which usually means they are higher-wage employees, the “choices” available to them may be less than optimal, or they may have no real choices at all.

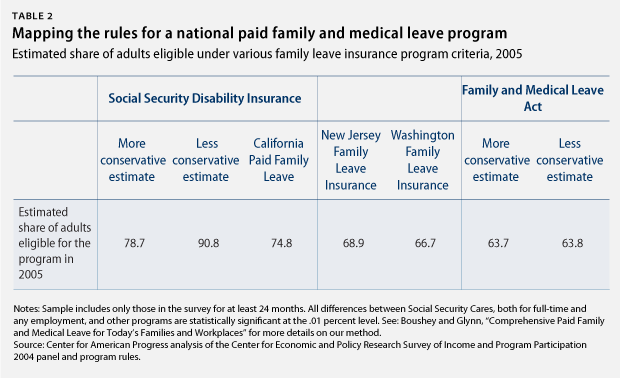

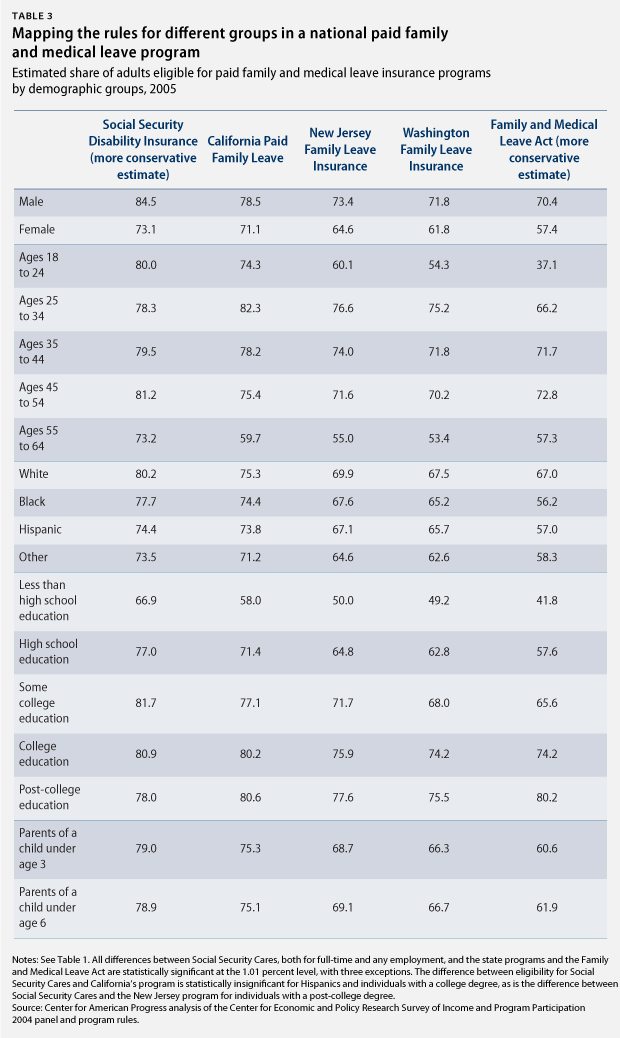

Using our preferred eligibility criteria, the vast majority of workers would be covered under Social Security Cares. (see Tables 2 and 3) Using the most conservative estimates, nearly four in five adults (78.7 percent) would be eligible for paid leave, including almost three-quarters of women (73.1 percent), and almost four in five parents with young children (79.0 percent with a child under age 3, and 78.9 percent of parents with a child under age 6). Almost four in five adults between the ages of 25 and 35 would be covered (78.3 percent); nearly four in five African Americans (77.7 percent); and nearly three-quarters of Latinos (74.4 percent) would be eligible for Social Security Cares.

As a matter of comparison, according to the U.S. Census Bureau between 2006 to 2008, two-thirds (66.3 percent) of new mothers with a bachelor’s degree or more were able to take paid leave. (see Figure 2) But less than one in five (18.5 percent) new moms with less than a high school diploma had access to paid leave after the birth of a child—the same rate of coverage as in the early 1960s. In contrast, two-thirds (66.9 percent) of workers with less than a high school degree would be covered under Social Security Cares.

Social Security Cares will increase the labor force participation of caregivers

Though it may seem counterintuitive, offering paid leave makes workers more likely to return to employment, and to return more quickly, than if they are fired or forced to quit when they need caregiving leave. Returning to work more quickly means that skills do not have time to atrophy, and job tenure and seniority is accrued more rapidly. Both wages and retirement income increase as a result.

Enabling more people to work consistently throughout their lives also boasts the benefit of increasing payroll tax contributions to the Social Security Trust Fund. The benefits here are twofold: Workers’ greater contributions result in both greater economic security in their old age and contribute significantly to the Social Security coffers.

At present, women are more likely than men to leave a job or shift from full-time to part-time work when a new child arrives. Women also are more likely to leave a job or make the shift from full- to part-time work in order provide ongoing care to an elderly, ailing parent. But when men are the workers providing family care, their working hours decrease as well. Some workers are left with little option but to make such a choice, as they face workplaces with no paid family leave policies or inflexible scheduling practices.

The fact that many caregivers must drop out of the workforce to provide family care can lead to a lifetime of greater economic insecurity. As workers with care responsibilities withdraw from the workforce or limit their time at work, they take home less income in the short run; are less likely to earn raises and promotions at the same pace; have less access to workplace retirement benefits; earn less in Social Security retirement benefits; and accumulate lower lifetime earnings. If workers have access to paid, job-protected family leave upon the birth of a child or the serious illness of a family member, they are much more likely to be able to return to the workforce and to have higher earnings over their lifetimes.

While there are a variety of reasons that a worker would need to take paid leave, most of the research focuses on maternity leave. National data consistently shows that access to any form of parental leave, paid or unpaid, makes women more likely to return to work after giving birth. Among new mothers who worked while pregnant and were able to take paid leave, 9 in 10 (87.4 percent) returned to work within one year after giving birth. In contrast, among new mothers who had to quit their jobs, just less than half (48.2 percent) returned to work within a year, and among new mothers who were let go, more than half (55.7 percent) of women returned to work within a year.

What’s more, mothers who were able to take paid maternity leave after the birth of their first child also have present-day wages that, up to 16 years after they had that child, are 9 percent higher than the wages of other mothers, even after controlling for personal and job-related variables.

Workers who experience a temporary disability, serious illness, or injury also benefit from the ability to take paid time away from work to recover. In the absence of paid leave, workers may need to return to work earlier than is medically advisable for economic reasons. This can increase the likelihood of relapsing, and depending on the nature of the work may put the worker or others in danger. Access to paid time off is associated with workers recovering more quickly and completely.

Unfortunately, reliable, nationally representative analysis on the employment impacts of short-term but serious illnesses for workers is not currently available. But it is not unreasonable to suspect that the effects of staying in the labor force for workers who need medical leave would be similar to those of workers who need caregiving leave. In 2001 25 percent of dual-income couples and 13 percent of single-parent families filed for bankruptcy after having to miss two or more weeks of work due to personal illness or the illness of a family member. At least a portion of those bankruptcies would likely have been avoided had those workers had access to a national paid family and medical leave insurance program.

Social Security Cares will promote gender equity

Most working fathers (65 percent) say that they believe both parents should divide caregiving responsibilities within a family equally. Yet only 30 percent actually report having an equal division of labor within their home. At least some of this problem is because men are less likely to take leave after the arrival of a child than women.

It is important to note that men do not eschew unpaid leave because they do not want to take care of their families, but rather because the wage gap and lack of paid leave currently makes it economically rational for women to take time off rather than men. Paid leave would enable men to take caregiving leave, both to bond with new children and to care for ill family members, without requiring a total loss of income for that time.

While the gender wage gap has narrowed some as women’s education attainment and labor force participation has increased, it has remained static for the last several years, with full-time working women’s median annual income in 2010 coming in at a paltry 77 percent of men’s. Women of color are disadvantaged even further because their earnings are even lower relative to white men than for white women. Even when controlling for occupation, education, and experience, economists cannot explain about 10 percent of the wage gap.

Because of the gender pay gap and women’s lower lifetime labor force participation, women and their families lose an astounding $431,000 on average in income over a lifetime. For women under age 35, the wage gap between mothers and non-mothers is greater than the gap between women and men. The “mother’s wage penalty” is estimated at approximately 7 percent per child, and just under one-third of the gap is attributed to the consequences of taking leave. More than 40 percent of the gap cannot be attributed to any measurable productivity-related characteristic.

The Family and Medical Leave Act provides both men and women with equal amounts of leave, which should help close the gender gap. By giving both mothers and fathers access to leave and both men and women time to care for a seriously ill loved one, the law should increase leave-taking among men and thus help reduce the lifetime gender gap.

Yet because the leave is unpaid, men have lower take-up for caregiver leave than do women (although they have higher take-up for leave for their own serious illness). Recent research in California is finding that when paid leave is offered, men are much more likely to take it. Because about 10 percent of the gender wage gap is due to differences in the work histories of men and women, encouraging men to take family leave would help to reduce the stigma around taking leave, which is an important component of reducing the gender wage gap.

Because leave under the Family and Medical Leave Act is unpaid, workers, especially male workers, often cannot afford to take it. Almost 80 percent of eligible workers who did not take leave after a qualifying life event said that they would have had it been paid. Because this leave is unpaid, men are less likely to take it to care for a new child than women. This is both because men tend to earn more than women, and because men often do not think that unpaid leave is intended for them.

There is reason to believe that the unexplained portions of the wage gap, both between men and women and between mothers and childless women, are due to discrimination. Because women tend to be the caregivers for their families and are more likely to take time out of the workforce when family care needs arise, employers may erroneously believe that women are less serious about their careers and are less dependable workers than men. Enabling men to take caregiving leave would help to challenge these outdated gender stereotypes and promote more gender equitable workplaces for both men and women.

Social Security Cares would save businesses money

While the majority of workers do not have access to paid family and medical leave, there are some who do. Their employers recognize that offering generous benefits is not only a good recruiting tool, but it also saves money in the long run. Large corporations employing professional workers, among them Microsoft Corp. and Google Inc., often provide a host of benefits, including paid leave, to help recruit and retain workers. A national paid family leave insurance program would help level the playing field for smaller businesses that may not be able to afford to finance generous leave policies on their own.

When workers are faced with a serious illness or caregiving responsibilities that are incompatible with their work schedules, those who do not have access to paid leave often have no choice but to quit their jobs. This not only has a negative economic impact on individuals and their families, but on the businesses that were employing them as well. With the exception of the most highly trained and highly paid professions, which are more likely to have access to paid leave already, it costs businesses about one-fifth of an employee’s salary to replace them. A paid family and medical leave insurance program would not only help businesses retain the valuable experience and instititional knowledge their workers possess by helping those workers stay employed, but would also save them money.

Surveys of employers in California after the implementation of the state’s paid family leave insurance program illustrate how national legislation could benefit not just workers but businesses as well. The vast majority of employers reported either no effect or a positive effect on employee morale (99 percent); profitability and/or performance (91 percent); and productivity (89 percent). Notably, small businesses were even less likely than large employers (those with less than 100 workers) to state that they experienced any negative effects from the law.

Paid leave insurance saves money by reducing the costs associated with turnover and improving morale and productivity. Because many (though certainly not all) employers already offer some form of paid leave—be it paid parental leave, paid sick days, or vacation time—a federal wage replacement program would help them lower their costs. Approximately 60 percent of employers in California reported coordinating the benefits they offered with those coming from the state paid leave fund. This allows employers to offer the same level of benefit, at a much lower cost. About 93 percent of employers also reported either no change or less turnover as a result of the paid leave program in California, adding additional cost savings to businesses there.

Conclusion

American families are different today, and there is no evidence to suggest that we will return to the male-breadwinner/female-stay-at-home-caregiver model. It is high time that workplace policies start to reflect the way our families live today, rather than remaining rooted in outdated notions of what a family is “supposed” to look like.

Implementing a paid family and medical leave program such as Social Security Cares would be a good first step in bringing the United States up to par relative to other nations’ labor standards, and it would help facilitate the dual roles of worker and caregiver that most adults will experience at some point in their lives.

But Social Security Cares would not help just individual workers and their families. It would also benefit society at large. Families’ immediate and long-term economic stability, as well as their ability to provide care to aging baby-boomers, would improve sharply if workers’ access to paid family and medical leave were increased. This would promote gender equity and help close the wage gap, which would promote in turn greater labor force participation of women. With costs this low and benefits this high, implementing a national paid family and medical leave program is not only about being “nice” to workers—it also makes economic sense.

Heather Boushey is a Senior Economist at the Center for American Progress. Sarah Jane Glynn is a Policy Analyst with the Economics team at the Center.