This column was originally published on MarketWatch.

The longer you spend with January’s employment report—released Friday from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, or BLS—the more you will like it. But just how long that good feeling will last depends on the Federal Reserve.

You could read just the top-line numbers of the report and go home perfectly happy; but this report really gets impressive when you dig deeper into the data. Strong job gains for November and December were revised upward to be even stronger. The noisy month-over-month wage-growth number was excellent, while wages were up 2.2 percent for the year. Most importantly, the economy added another quarter million jobs, even as all four measures of the unemployment rate went up. The addition of new jobs and even more new job seekers means that there is more room to grow before inflation becomes a problem. This is not only surprising; it’s great news—particularly if you’re hoping policymakers don’t choke off a recovery before it gains steam.

Let’s talk about why that last point is such a big deal. This past spring, three Princeton economists—including Alan Krueger, the former chair of the Council of Economic Advisors for the Obama administration—presented a depressing study of the U.S. labor market. Their conclusion was that many of the workers pushed into long-term unemployment by the Great Recession would not come back into the labor market because the U.S. economy typically gives up on these workers for good. Historically, they are right. And under normal circumstances, that research—along with another round of downward revisions to the Congressional Budget Office’s estimate of potential gross domestic product, or GDP—suggest that the Fed should be thinking about raising interest rates soon.

The clearest counterargument to that view, however, is to consider the mid 1990s, when the Fed held off on raising rates in the face of an unemployment rate a lot like today’s. Because of the Fed’s inaction, the unemployment rate kept falling another 5 years, bottoming out below 4 percent. As the economy continued to accelerate, labor-force participation rates picked up, and the nation saw GDP and real wage growth unequaled in the modern U.S. economy. This month’s jobs report suggests that the dream of the 1990s is alive at the Bureau of Labor Statistics, and that’s great news for all of us.

Meanwhile, at the Fed, the major question now is whether Chair Janet Yellen can repeat the success of the 1990s and sway the Federal Open Market Committee, or FOMC, to wait for signs of inflation before raising rates to slow down the economy. This should be an easy task: the Fed is charged with targeting maximum employment and stable prices—typically defined as 2 percent inflation. Given that today’s inflation rate is below 2 percent, that the labor force expanded fast enough to raise the unemployment rate this month, and that treasury yields are pointing to low inflation expectations, the data clearly say wait. Yet that’s not what we hear when Fed governors speak, with Charles Plosser, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, saying last week “Will inflation begin to drift back up toward our target? I think it will.” He could be right, but if he has his way, we’ll raise interest rates and slow the economy down before we get to find out.

The strength of the U.S. dollar immediately after the jobs report indicated that the markets interpreted Friday’s numbers as a sign the inflation hawks’ position was strengthened, and we should expect rate increases sooner rather than later. The top-line numbers could be interpreted as supporting this view, but digging deeper tells a different story.

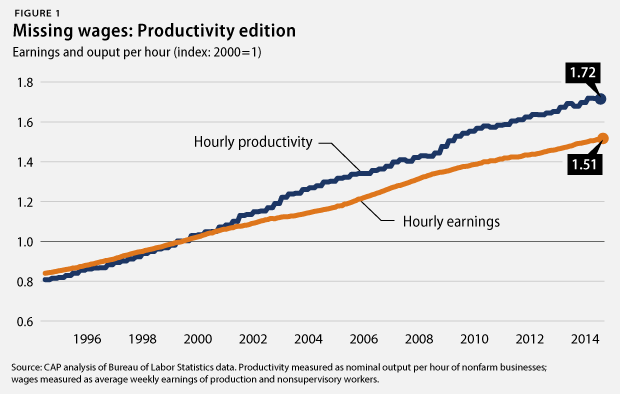

Wage growth was among the strongest and most discussed indicators—month-over-month average hourly earnings were up about 0.5 percent after a surprising decline last month. The year-over-year increase, however, was just 2.2 percent, which is stronger than in quite some time, but barely above inflation and way behind productivity growth increases since the recession.

So with no price pressures, real or expected, and no apparent wage pressures, why should the Fed be thinking about tightening? We are back to talking about labor-market slack again, and here, the surprising success of the past year is paying dividends. The labor-force participation rate is essentially unchanged from January 2014, at 62.9 percent. But given our aging population, this number reflects more working-aged people coming off the sidelines and entering the labor market, both increasing potential GDP and reducing inflationary pressures. Raising GDP by reducing the unemployment rate can increase inflation, but bringing more workers into the labor force means raising potential GDP, which in turn, reduces pressure on inflation.

All told, January was a great month, and the longer you spend with the data, the better they look. The labor market has been picking up steam for months and—in the parlance of the NFL—is in “Beast Mode” right now. If we’ve learned anything recently, it’s that you don’t try to overthink things when Beast Mode is doing its thing. But trust me, not all monetary policy aficionados are football fans. We can only hope that the Fed has learned from a key lesson from the Super Bowl: when Beast Mode is an option, don’t do anything to get in the way of success.

Michael Madowitz is an Economist at the Center for American Progress.