Introduction and summary

In 2016, sandwich chain Jimmy John’s made headlines when it agreed to stop requiring its workers to sign noncompete agreements through a settlement with the attorneys general of New York and Illinois.1 The case caught many worker advocates by surprise. It is well known that, in an effort to protect company trade secrets, corporations often require CEOs and top talent to sign agreements not to join rival firms for a certain period of time. But Jimmy John’s was requiring low-wage sandwich-makers—workers unlikely to hold valuable company secrets—to agree not to work for rival sandwich shops for up to two years after their employment ended.2

Emerging research and litigation have revealed that Jimmy John’s is not the only company to use this tactic. From fast-food workers and check-cashing clerks to health care providers and engineers, companies are requiring workers across income and educational attainment to sign restrictive contractual agreements, such as noncompete contracts and even “no-poaching” agreements between firms.3 Employment contracts often carry these requirements as well as several other provisions—including mandatory arbitration requirements, class-action waivers, and nondisclosure agreements—that may restrict workers’ rights on the job and their ability to leave the job for a better one or to start a new business.

As a result, too many American workers are unfairly stuck in jobs they do not want but cannot leave. Some surveys find that nearly 40 percent of the American workforce is now or has previously been subject to a noncompete agreement at work.4 In addition, in 2016, more than half of franchisors required franchisees to sign no-poaching agreements that prevented their workers from moving between locations.5

Noncompete and no-poaching agreements not only prevent individual workers from moving to better jobs that will allow them to earn more and advance in their careers; they also contribute to larger negative trends in the American economy that are reducing economic dynamism, impeding labor market competition, and, consequently, driving wage stagnation across the economy.

This report demonstrates how abusive noncompete and no-poach agreements harm workers across income levels and the larger U.S. economy; and it asserts that states have the power to protect workers from these agreements. Reversing this practice should be a priority for policymakers who want to support working families.

Strong wage growth is central to the health of the American middle and working class.6 All but the wealthiest of American families rely on wages—rather than wealth—to support themselves and save for the future. Throughout the middle of the 20th century, working Americans enjoyed rapid improvements in their standard of living as wage growth increased in tandem with rapidly expanding American productivity.7

Over the past four decades, however, American wages have stagnated, even as productivity has continued to grow. Since the Great Recession, growth in wages has just barely outpaced inflation.8 Moreover, despite low unemployment rates and strong gross domestic product (GDP) growth, real wage growth has been flat since President Donald Trump took office in January 2017.9

Noncompete and no-poaching agreements have contributed to this trend. A small but growing body of research indicates that when workers are forced to sign these sorts of agreements, their ability to bargain for better wages is reduced since they cannot leave a job—or even threaten to leave a job—for a competitor. One academic study found that workers’ wages were significantly lower in states with strict enforcement of noncompetes than they were in states with the most lenient enforcement of noncompete agreements; the study also found that this wage gap increased as workers aged.10

Similarly, in a 2016 report, the U.S. Council of Economic Advisers concluded that “it is likely that the primary effect of these [noncompete] agreements is to impede worker mobility and limit wage competition.”11

In addition, noncompete agreements can prevent low- and middle-income families from building wealth through entrepreneurship and small business ownership. Business owners in the United States enjoy significantly higher levels of wealth than those who do not own a business—with even larger wealth gains for African American and Latino business owners compared with African American and Latino non-business owners.12 However, as previous CAP research has shown, entrepreneurship has been on a long-term decline since the early 2000s.13

Noncompete agreements may exacerbate this problem by preventing workers from striking out on their own to create rival firms. Some academic studies find that entrepreneurs launch startups at lower rates and have a harder time attracting employees for businesses in jurisdictions that strictly enforce these sorts of agreements.14

Moreover, this is not just a hinderance for entrepreneurs but may also inhibit regional economic growth, as companies may receive less benefits from co-locating near skilled labor pools when noncompete and no-poaching agreements are used at high rates.

Raising wages and increasing the ability of Americans to become entrepreneurs will require myriad policy reforms, including those to revive federal antitrust protections; regulate abusive employment contracts; ensure that workers can come together in strong unions; raise the minimum wage and overtime standards; promote in-demand skills; and strengthen government supports for small business and access to credit. The Center for American Progress and the Center for American Progress Action Fund have previously released several papers advocating that the government take action in all these areas.15

State policymakers, however, can also significantly increase workers’ power in the labor market by enacting state-level legislation to protect them from abusive noncompete and no-poaching agreements. Indeed, state legislatures and enforcement agencies are increasingly taking action to establish these protections, and groups ranging from progressive pro-worker advocacy organizations to conservative free market think tanks to academics are supporting these efforts.16

While several members of Congress have also introduced reforms to strengthen noncompete and no-poaching protections, under the current leadership of Congress and the White House, federal action is unlikely.17 Indeed, President Trump allegedly used particularly broad noncompete contracts for his campaign that covered volunteers and the employees of contractors.18

This report outlines three concrete solutions that states should take to prevent corporations from using these sorts of agreements to suppress competition and workers’ wages and to instead boost workers’ pay and freedom in the economy:

3 ways to support competition and boost worker pay

1. Ban noncompete contracts for most workers

States should limit noncompete contracts to the small portion of workers with the power to bargain over these agreements. In order to protect low- and middle-wage workers, states should ban these types of contracts for all workers earning less than 200 percent of the state’s median annual wage. In addition, lawmakers should prohibit companies that employ at least 50 workers from requiring more than 5 percent of their workforce to sign such a document.

2. Ban franchise no-poaching agreements

States should ban all no-poaching agreements among franchises. While several state attorneys general, under the authority of existing state antitrust laws, are taking action against fast-food corporations and other corporate franchisors that require franchisees to sign no-poaching agreements, clarifying legislation would help to ensure that courts do not rule against workers in the future and that corporations understand that no-poaching agreements are banned in all forms.

3. Give workers and enforcement agencies tools to enforce their rights

States should empower workers to stand up for themselves and should bolster enforcement agencies’ ability to protect workers by requiring companies to disclose all noncompete requirements in job postings and job offers; establishing significant penalties for use of illegal noncompete and no-poaching agreements; designating and funding enforcement agencies to pursue these sorts of cases; and allowing workers to sue companies that violate their rights.

By adopting these policies, states can also help to reverse larger economic problems, including wage stagnation, growing inequality, and stifled entrepreneurship.

The rise of noncompete and no-poaching agreements

A growing body of research demonstrates that corporations frequently use noncompete and no-poaching agreements in ways that limit employee mobility.19 Corporations often lock even the lowest-wage workers into these contractual agreements. Yet research also shows that strict enforcement of these sorts of contracts is associated with lower pay and decreased job mobility for workers, as well as weaker regional economic development. While the negative consequences of these agreements may be felt throughout the labor market, workers can be unaware of their existence or implications until years after they have signed them.

Noncompete agreements

Noncompete agreements—often included as part of an employment contract—require a worker to agree not to become an employee of a competing company or start a competing company upon leaving the firm. These agreements often last for a specific period of time and encompass a specific geography.

Typically, workers get no payment from the prior employer during the waiting period. On rarer occasions, the contract may require the employer to provide some portion of pay to the worker—so-called garden leave—for the duration of the post-employment waiting period or to commit to ongoing investment in the worker, such as professional training.

Proponents of noncompete contracts argue that they help spark innovation and investment in industry research and development since they allow corporations to protect their intellectual property and trade secrets as workers move among firms.20 In addition, proponents argue that noncompetes encourage investment in employee training since corporations do not have to fear well-trained workers being recruited by a competing firm.21

Yet signature of a noncompete agreement reduces a workers’ ability to leave a job—or even threaten to leave a job—since they are unable to advertise their skills or even be recruited by an employer’s competitor without the threat of litigation. When a worker wants to move to another job, they may be forced to move to a different field, where their skills are less applicable and the pay is lower.22

While the use of these provisions dates back centuries, corporations are increasingly engaging in litigation to enforce these agreements.23 According to a study commissioned by The Wall Street Journal, the number of workers sued by former employers for breach of a noncompete agreement rose by 61 percent between 2002 and 2013.24

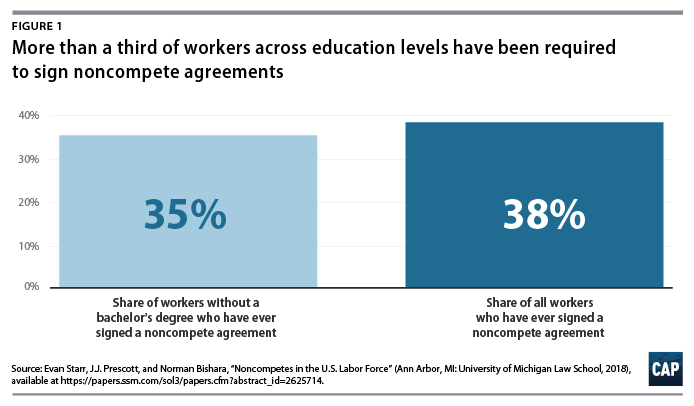

Moreover, there is evidence that the use of noncompetes is frequent across all wage levels and positions. Researchers from the University of Maryland and the University of Michigan, Evan Starr, J.J. Prescott, and Norman Bishara, recently released the findings of a survey of more than 11,500 workers, which found that 18 percent of U.S. workers—28 million Americans—are currently subject to a noncompete agreement and that 38 percent of workers have signed a noncompete at some point in their lives.25

While the survey found that highly educated workers were more likely to have signed such an agreement, among workers without a bachelor’s degree, the numbers were still startlingly high. More than one-third reported signing a noncompete at some point in their career, and 14 percent were currently covered by such an agreement.

Similarly, in a 2017 survey of more than 900 workers conducted by University of Princeton economist Alan Krueger and University of Chicago Law School professor Eric Posner, nearly 1 in 4 workers reported that they were currently bound by a noncompete agreement or had been in the past; and 15.5 percent of workers reported that they were currently covered by a noncompete agreement.26

As a result, the enforcement of these agreements appears to be constraining the power of workers to bargain for higher wages and benefits on the job. The level of enforcement depends on the state, since state laws governing how and when noncompete agreements can be enforced vary widely.

Research finds that workers may pay a penalty in the form of lower wages when they live in a state with strict enforcement of noncompete contracts—a penalty that is compounded as workers age. According to a 2016 report from the U.S. Department of Treasury, living in a state with strict enforcement of noncompete contracts, compared to one with the most lenient enforcement, is associated with a 5 percent reduction in pay for a typical 25-year-old worker.27 For a typical 50-year-old worker, living in a state with strict enforcement is associated with a 10 percent wage penalty. Furthermore, a 2011 academic study found that even top executives are paid less in states with strict noncompete laws.28

Moreover, employers may not tell workers about the requirement to sign a noncompete until they have accepted a job. This delayed notification limits workers’ ability to pursue other job opportunities that may not carry this requirement or to negotiate for the pay and benefits necessary to compensate for signature of such an agreement.

For example, Starr, Prescott, and Bishara found that workers only benefited from signing an agreement when they were informed of a noncompete requirement in advance of their acceptance of a job offer.29 According to the authors, when corporations provide this sort of early notification, workers signing a noncompete agreement earn 9.7 percent higher wages, receive 11 percent more training, and are 6.6 percent more satisfied in their job than workers who not bound by a noncompete contract. In contrast, workers who are first asked to sign a noncompete after accepting a job are 12.5 percent less satisfied in their job and experience no wage and training benefits relative to nonsigners.30

Despite the clear detriments to workers, one-third of noncompetes are signed after a worker has accepted the job offer. Moreover, only 1 in 10 workers reported negotiating over the terms of the noncompete agreement.31

Similarly, in a 2011 survey of electrical engineers, Boston University’s Matt Marx found that nearly 70 percent of workers signing a noncompete received the agreement after the offer letter, and approximately a quarter of these workers were asked to sign the agreement on their first day of work.32

While noncompetes may support the interests of an individual firm, by limiting workers’ ability to switch jobs, they may harm the larger economy. High levels of job mobility—the movement of workers between jobs—can help to stimulate the larger economy by fostering innovation through information-sharing; entrepreneurship as workers leave jobs to start new companies; and even regional industry development, since firms can co-locate to share local talent pools.

The quintessential example of this sort of regional co-location is the Silicon Valley technology hub. Indeed, California famously banned the enforcement of noncompete agreements.33 It is hard to determine how this ban on enforcement has affected the region, and as discussed in the following section, there is significant evidence that California employers still include unenforceable noncompetes in workers’ employment contracts.

However, a number of studies indicate that strict enforcement of noncompete laws restricts job mobility and the growth of entrepreneurship in a jurisdiction.34 For example, academic research from Marx, Deborah Strumsky, and Lee Fleming found that job mobility in Michigan fell by 8 percent after the state started allowing enforcement of noncompetes in 1985.35 And a new working paper published by the U.S. Census Bureau’s Center for Economic Studies found that tech workers in states that enforce noncompete agreements had 8 percent fewer jobs over an 8-year period compared with workers in states that do not allow enforcement of noncompete agreements.36

The Census Bureau study also has important implications for state policymakers focused on retaining highly skilled workers. Workers in enforcing states were more likely to move across state lines while staying within their industry—perhaps to avoid the geographic restrictions of the noncompete agreement. Looking specifically at Hawaii, the study found that after the state instituted an outright ban on noncompetes for tech workers, job mobility increased by 11 percent and new hire wages grew by 4 percent.37

Finally, some academic studies have found that restricting the enforcement of noncompetes is associated with an increase in patents and firm startups and that it influences the ability of new firms to attract top talent.38 For example, in a 2011 study, researchers Sampsa Samila and Olav Sorenson reviewed nine years of data, finding that venture capital funding had stronger positive effects on the number of patents licensed and firm startups in states with weaker enforcement of noncompete agreements.39 However, another academic study that examined within-industry spinouts—businesses started by employees in the same industry of the firm they are leaving—indicated that, in some instances, strict enforcement of noncompetes may help screen out weaker start-ups. While the study found that states with strict enforcement of noncompete agreements had fewer spinouts, the companies that were created were typically larger and had better survival rates than other types of new startups.40

Despite these ambiguous findings, the majority of emerging research on noncompetes indicates that workers bare significant burdens due to these laws, and regional economies may suffer as well.

No-poaching agreements

The use of no-poaching agreements in franchise chains is similarly limiting labor market mobility among fast-food workers and other sorts of franchise employees. Through the franchise system, corporate business owners, or franchisors, provide licenses to independent business owners, or franchisees, that grant them the right to operate a business under the corporation’s name and use its systems in exchange for a startup fee and ongoing royalty payments.41

Corporate franchisors often require franchise owners to sign no-poaching agreements as part of a voluminous and confidential franchise contract.42 However, workers only find out about this limitation when they attempt to move to another store in the franchise chain that provides better career advancement opportunities, hours, pay, or working conditions.

By barring franchises from recruiting the skilled employees of another franchise, these agreements can drive down workers’ wages and overall franchise labor costs. Yet industry wages are already very low. For example, fast-food cooks make an average hourly wage of $10.39 per hour, or $21,610 annually, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics.43

Moreover, no-poach agreements do not always work to a franchisee’s advantage since they can also function as a barrier for individual franchise employers that are searching for experienced workers.

Research shows that no-poaching agreements have been on the rise in recent years. According to academics Alan Krueger and Orley Ashenfelter, who examined the franchise contracts of 156 major franchisors operating in the United States, the share of franchisors that included these sorts of clauses in their contracts grew from one-third to more than one-half—58 percent—of all franchisors between 1996 and 2016.44

Consequently, no-poaching agreements could affect millions of workers. In a report prepared for the International Franchise Association, IHS Markit Economics estimates that U.S. franchises employed 7.9 million workers in 2017.45

State attorneys general are increasingly taking action to better police the use of these agreements (as discussed in the next section). Yet the corporate structure of the fast-food industry has allowed corporations to suppress the pay and economic mobility of low-wage workers for far too long.

State laws and enforcement actions

States have considerable power to protect workers from abusive noncompete and no-poaching agreements. Many state legislatures are working to strengthen the existing laws protecting workers from aggressive noncompete agreements, particularly when it comes to low-wage workers.46 And increasingly, state attorneys general are taking action to protect workers from abusive noncompete and no-poach agreements.47

Legislation and enforcement of noncompete agreements

Historically, case law has governed the use of noncompete agreements. However, most states have also enacted legislation providing guidance on how courts should enforce noncompete contracts, such as whether a court should modify or strike down an overly broad agreement. Within these legal frameworks, courts typically have discretion to refrain from enforcing a noncompete agreement that is not necessary to protect the legitimate interests of a business and that limits workers’ ability to obtain decent wages.48

In addition, several states provide limited protections to ensure that contracts are not drafted to be overly burdensome to workers or to protect certain groups of workers from these anti-competitive practices. For example, at least six states use state statutes to limit the total duration of noncompete agreements to a specific period of time, ranging from one to two years; and a number of states narrowly exempt specific occupations from coverage under noncompete laws, including health care providers, broadcasters, accountants, and tech workers.49

These laws also help protect public interests. For example, at least 12 states exclude doctors, and sometimes other health providers, from noncompete agreements in order to help ensure public access to essential services. In addition, at least seven states and the District of Columbia have adopted similar protections on enforcement among broadcasters, helping to protect freedom of speech.50

Three states—California, Oklahoma, and North Dakota—go even further by banning virtually all enforcement of noncompete agreements.51 These laws do not ban a worker from signing a noncompete, but they do ban a court from enforcing the agreement.

Previously, many advocates of vigorous labor market competition believed that a ban on enforcement would accomplish the same goal as an outright ban on these agreements, as it seemed unlikely that corporations would ask employees to sign an unenforceable document.52 Yet research has revealed that this is not the case. Workers in states where noncompetes are unenforceable are required to sign these agreements at similar rates as workers in other states. For example, 19 percent of workers in California are subject to noncompetes—a rate slightly higher than the national average.53

Researchers and worker advocates are increasingly asking whether corporations include unenforceable noncompete agreements in employment contracts due to the chilling effects they may have on job mobility and wage increases.54

While some workers in states that have banned the enforcement of noncompetes may know their rights under the law or consult an attorney before signing such an agreement, it is reasonable to assume that others will trust that the documents provided by their employer are legally binding and respond accordingly. The same is true among workers for whom a court may be unlikely to uphold a signed noncompete—such as low-wage workers or workers who do not possess any trade secrets.

Existing laws place a considerable burden on workers to both know their legal rights and be willing to take on a former employer in court in order to protect themselves. And even when a worker does decide to fight an illegal noncompete clause, they can typically hope for little more than the court to order that the noncompete not be enforced. In many states, the court would order that the agreement be narrowed to fall within legal limits. Furthermore, since available legal remedies in these cases do not require employers to pay penalties or back pay to aggrieved workers, these workers would be required to pay a lawyer out of their own pockets. This presents an especially large hurdle for low-wage workers.

Even higher-wage workers report leaving industries of expertise due to the signature of a noncompete, rather than fight its enforcement. According to a 2011 study of engineers, about one-third of workers who signed noncompete agreements left their chosen industry when they changed jobs.55 Furthermore, while larger firms may choose to take on the risk of potentially defending themselves in order to hire top talent covered by a noncompete agreement, small and growing firms may be unable to shoulder that same risk.56

Existing employers, on the other hand, bear little risk when requiring workers to sign noncompete agreements. While an individual worker could sue an employer over an overly broad noncompete agreement, this sort of legal action generally does not result in any payouts to workers, and even unenforceable clauses will intimidate some employees into compliance.

For these reasons, state attorneys general have taken on a number of noncompete cases in recent years on behalf of low- and middle-wage workers. As discussed above, in a settlement with the attorneys general of New York and Illinois, Jimmy John’s agreed to stop requiring its sandwich-makers to sign noncompetes and to pay $100,000 to fund “education and outreach programs to promote best practices by the employers.”57

Jimmy John’s practice of requiring store staff to sign noncompete agreements was first exposed when employees brought a class-action lawsuit against the company and one of its franchises. While the suit was first focused on allegations that the firms were requiring employees to work off-the-clock, the workers amended the complaint in 2014 to include allegations that the companies required them to sign noncompete agreements that were overly broad and “oppressive.”58

Following the agreement, New York’s attorney general also announced settlements with Law360, a legal news website owned by LexisNexis; Examination Management Services Inc., a nationwide medical information services provider; and WeWork, a provider of shared workspaces for rent. In these settlements, the companies agreed to stop requiring most employees to sign noncompetes.59

Simultaneously, policymakers in a number of states began working, often on a bipartisan basis, to ban or otherwise limit the enforcement of noncompete agreements among low- and middle-wage workers and to expand protections for all workers.

For example, Gov. Bruce Rauner (R-IL) signed the Illinois Workplace Freedom Act into law in 2016. The law, which was sponsored by Democratic lawmakers but received wide-ranging support from lawmakers of both parties, bans noncompete agreements for workers earning less than either $13 per hour or the state or local minimum wage.60 Last fall, the state’s attorney general, Lisa Madigan, announced a lawsuit alleging that Check Into Cash, a national check-cashing and payday loan company, was violating the Workplace Freedom Act by failing to revoke noncompete agreements among the company’s low-wage clerks.61

In Massachusetts, policymakers enacted legislation this year that limits the use of noncompete agreements among low-wage workers and institutes several reforms to ensure higher-wage workers are treated fairly.62 For example, the law prohibits the enforcement of noncompetes for all workers who are classified as nonexempt under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), which includes all employees paid on an hourly basis as well as salaried employees earning less than $23,600 per year, among other qualifying criteria; limits the duration of an agreement to nine months; and requires companies that exercise these agreements to pay garden leave equivalent to 50 percent of a workers’ pay for the duration of the noncompete.63

Yet in contrast to the Illinois law, which specifies that “a covenant not to compete entered into between an employer and a low-wage employee is illegal and void,”64 the Massachusetts law only prohibits the enforcement of noncompetes, rather than outright banning the signature of such agreements.65 As a result, it is possible that corporations will continue to require workers to sign unenforceable noncompete agreements due to their chilling effects on worker mobility. Moreover, legal experts have raised concerns that the new law includes a loophole that would allow corporations to pay workers significantly less than the bill’s specified garden leave requirements.66

Other states—such as Pennsylvania, Maine, New York, New Jersey, Washington, and Vermont—and New York City debated legislation that includes outright bans of employers entering into noncompete agreements.67 Some of these reform measures also increase penalties on lawbreakers; raise the costs to employers of requiring employees to sign noncompete agreements; and ensure that workers know their rights.

These sorts of debates will likely continue in the 2019 legislative session as several states consider noncompete reforms.

State enforcement of no-poaching agreements

While state legislatures are debating and enacting laws to limit the use of noncompete agreements, to date, no state has enacted legislation to bar franchisors from requiring no-poaching agreements. This is despite the fact that many worker advocates and state enforcement agencies argue that corporate franchisors break existing state and local antitrust laws when they enter into these agreements.

State attorneys general, however, are adopting aggressive enforcement strategies to prevent their use. Agreements not to poach or compete for workers among unaffiliated businesses are a clear violation of state and federal antitrust laws that were enacted to prevent employers from colluding to keep wages low. For example, in 2010, the U.S. Department of Justice reached a settlement with Adobe Systems Inc., Apple Inc., Google Inc., Intel Corp., Intuit Inc., and Pixar after the agency found that the companies had agreed not to solicit each other’s top employees.68 Under the terms of the agreement, the corporations were prohibited from entering into any agreement that prevented any person from recruiting or competing for employees.

Yet corporate franchises often claim that a franchisor and its franchisees should be held to a different standard since they function as a single entity rather than competitors. At times, courts have upheld no-poaching agreements among franchise establishments based on this rationale.

For example, in the 1992 case Williams v. Nevada, a U.S. district court upheld the right of Jack in the Box Inc.—formerly Foodmaker—to enter into an agreement with each of its franchisees to restrict hiring of management employees, arguing that the franchisor and its franchisees could not collude since they functioned as “a single enterprise.”69

However, this immunity was called into question by the Supreme Court’s 2010 ruling in American Needle v. National Football League, which narrowed the multifactor test for determining whether the franchise system could be determined as a single economic operation and, therefore, deemed incapable of collusion.70

Currently, this pushback is increasing, as attorneys general in a number of states are investigating the use of no-poaching agreements among fast-food franchisors and taking action under existing state law. In July 2018, attorneys general from 11 states launched an effort to investigate the use of no-poaching agreements in eight fast-food chains.71 Washington state Attorney General Bob Ferguson is leading this fight. Since July, he has obtained agreements from 39 corporate franchises to end the use of no poach agreements nationwide in order to avoid a lawsuit from his office.72

Ferguson alleged that the practice violates the state’s Unfair Business Practices-Consumer Protection Act, which restricts “unreasonable restraints of trade.”73 In addition, Ferguson has filed a lawsuit against Jersey Mike’s, a national sandwich franchisor, after it refused to remove no-poach agreements from its contracts.74

As a result of these actions, many franchisors are changing their practices. However, enacting clarifying legislation to protect workers from franchise no-poach agreements will help to ensure that these companies adhere to these commitments and that workers outside of Washington state are able to enforce these protections.

Policy recommendations

State policymakers have considerable power to help restore competition in the labor market by protecting workers from abusive noncompete and no-poaching agreements. While state legislatures and attorneys general are taking action to better protect workers, and several think tanks and academics have endorsed various reforms, no single strategy has emerged as the best path forward.75

This experimentation promises to raise standards for workers. It is particularly encouraging that lawmakers in some states are responding to recent lawsuits and emerging research by banning the use of noncompetes among low-wage workers.

But more needs to be done. Most existing state laws focus on how courts should police legal disputes over noncompete agreements, rather than banning the signature of these sorts of agreements in the first place. And no state legislature has taken action to better regulate franchise no-poaching agreements.

As states move forward, lawmakers should focus on policies that ban noncompete agreements for low- and middle-income workers; clarify that no-poaching agreements among franchises are illegal; raise costs for corporations that violate the rules; and create stronger avenues for enforcement of the law.

Recommendations to boost workers’ pay and freedom in the economy

While several states are debating policies to better protect workers from harmful noncompete and no-poaching agreements, most state laws are woefully inadequate. Here is how CAP’s recommendations stack up against some of the strongest existing state laws.

Recommendation: Protect low- and middle-wage workers from abusive noncompetes by banning noncompete contracts between corporations and workers earning less than 200 percent of the state’s median annual wage and prohibiting companies that employ at least 50 workers from requiring more than 5 percent of their workforce to sign such a document.

Existing state policies: Illinois bans corporations from requiring employees earning $13 per hour or less to sign a noncompete agreement. Other states—such as California, North Dakota, and Oklahoma—ban the enforcement, but not the signature, of a noncompete agreement. However, research shows that in states with these enforcement prohibitions, workers sign noncompete agreements at a similar rate as workers in states that enforce these agreements. Even unenforceable noncompete agreements may negatively affect workers’ job mobility and wages.

Recommendation: Ban all no-poaching agreements among franchisors and franchisees.

Existing state policies: Under the authority of existing state antitrust laws, several state attorneys general are taking action against fast-food corporations that require franchisees to sign no-poaching agreements. However, no state has enacted clarifying language to ban the use of these agreements.

Recommendation: Give workers and enforcement agencies tools to enforce their rights by requiring companies to disclose all noncompete requirements in job postings and job offers; establishing significant penalties for corporations that require workers to sign illegal noncompete or no-poaching agreements; designating and funding enforcement agencies to pursue these sorts of cases; and empowering workers to sue companies that violate their rights.

Existing state policies: A few states, including Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Oregon, require early disclosure of a noncompete agreement. After Illinois banned noncompetes among low-wage workers, Attorney General Madigan sued Check Into Cash, alleging that the company violated the state’s new law by failing to revoke noncompete agreements among the company’s clerks.

Some states are debating other policies to regulate noncompetes that would have a positive impact on workers, including reforms to allow courts more power to protect workers from overly broad contracts; efforts to limit the duration and geographic reach of these contracts; and requirements that corporations invest in the employees that sign noncompetes and provide them garden leave for the duration of the agreement.

To be sure, these proposals would have a positive impact on workers. However, CAP believes the following reforms will go significantly further to limit corporations’ use of these sorts of agreements in the first place.

1. Ban noncompete contracts for most workers

State policymakers should ban noncompete agreements for all workers earning less than 200 percent of—in other words, double—the state’s median annual wage. In addition, lawmakers should prohibit companies that employ at least 50 workers from requiring more than 5 percent of their workforce to sign such a document.

The legislation should function as an outright ban on agreements for these workers rather than a ban on the enforcement of the agreements. Moreover, part-time, seasonal, and temporary workers, as well as independent contractors, should be included under these protections.

By linking the ban to a state’s median wage, policymakers would protect both low- and middle-income residents while recognizing regional variations in earnings. In a high-income state such as California, workers earning up to $81,960 would be covered by such a measure, while the threshold would fall to nearly $65,600 for workers in Alabama.76

While this standard goes further than the recent reform in Illinois that protects low-wage workers, it is in line with legislation in other states. In New York, for example, state Rep. Jeffrey Dinowitz (D) partnered with the Department of Law last session to introduce a bill to ban noncompetes among workers earning less than $75,000 per year and require annual increases on the earnings threshold based on the consumer price index.77 Similarly, Oregon’s noncompete law—while not an outright ban on the agreements—prohibits the enforcement of noncompetes for workers earning less than the median wage for a family of four.78 Proposed legislation before the Vermont Legislature and Congress goes even further by banning nearly all noncompete agreements.79 Moreover, as discussed above, there is little evidence that middle-wage workers have the market power to negotiate over these sorts of agreements.

In addition, Colorado and Oregon laws attempt to limit the portion of workers that a company can require to sign a noncompete. Under Oregon law, only when employees are engaged in administrative, executive or professional work may a noncompete agreement be enforced.80 And Colorado limits employers’ ability to enforce these agreements to “executive and management personnel and officers and employees who constitute professional staff to executive and management personnel.”81 These executive-level employees are more likely to be able to negotiate over such covenants before entering into the agreement and after they leave the company.

While corporations often argue that these sorts of bans could limit their willingness to invest in worker training, research shows that companies often use these agreements in ways that result in little benefit to workers.82 For example, researchers find that workers who sign an agreement after accepting a job offer or without another employment option receive no training or wage benefit.83

Moreover, if the primary effect of noncompete agreements were to promote training, workers in states with strong enforcement of noncompetes would likely enjoy strong wage growth as they aged. Yet, as discussed above, not only do workers in strong enforcement states receive lower wages than workers in weak enforcement states, but this gap increases as workers age.84 Indeed, while the use of noncompete agreements has increased rapidly in recent decades, research shows that employer-paid training has declined significantly.85

Finally, while some states are advancing more limited reforms to protect only low-wage workers, middle-wage workers who currently sign these contracts could benefit from enhanced protections.86 For example, according to the Treasury Department’s 2016 report, less than half of all workers covered by noncompete agreements report holding trade secrets.87

If corporations’ primary reason for using these contracts was the protection of trade secrets, one would expect to see noncompete usage increase among workers with higher levels of education. However, according to the same Treasury Department report, the portion of workers without a college degree who are subject to these agreements is only slightly lower than the share of all workers who are currently covered by a noncompete agreement—15 percent and 18 percent, respectively.88

While opponents often argue that noncompete contracts are essential to protecting trade secrets or client lists, states typically have laws that prohibit the theft or disclosure of trade secrets and allow for nonsolicitation clauses to be included in employment contracts. Furthermore, a recent industry report shows that trade secret litigation—which requires corporations to demonstrate that a former employer misappropriated or threatened to misappropriate funds—is more frequent in California, a state that bans the enforcement of noncompete agreements.89

By passing noncompete protections, state lawmakers can encourage businesses to employ these more targeted strategies in order to both ensure confidentiality and protect the vast majority of workers who are harmed by these contracts.

2. Ban franchise no-poaching agreements

State legislatures can raise standards for fast-food workers by banning all no-poaching agreements among franchises. Under the authority of existing state antitrust laws, several state attorneys general are taking action against fast-food corporations that require franchisors to sign no-poaching agreements; however, to date, these actions have ended with settlements.

These agreements could be difficult to enforce nationwide, and in the past, courts have found against workers protesting no-poaching agreements.90 Indeed, the industry’s main lobby group—the International Franchise Association—has continued to state that “some form of ‘no-poaching provisions’” may be necessary for its members.91

Clarifying legislation would help to ensure that, in the future, courts do not find against workers and that corporations understand clearly that no-poaching agreements are banned in all forms.

While no state legislature has adopted such a law, worker advocates and academic researchers are beginning to coalesce around these ideas. Some scholars recommend that state legislatures adopt a “per se rule against no-poaching agreements regardless of whether they are used outside or within franchises.”92

In addition, Sen. Cory Booker (D-NJ), Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) and Rep. Keith Ellison (D-MN) introduced legislation this year to ban no-poach agreements and give the Federal Trade Commission enforcement powers.93 While the bill has little likelihood of passing in the near term, similar measures could be instituted at the state level.

3. Give workers and enforcement agencies tools to enforce their rights

Even in states that ban restrictive workplace contracts, workers frequently do not know their rights or have little power to exert them. While progressive state attorneys general are increasingly stepping in to protect workers from abusive employment contracts, state legislatures should enact reforms to bolster enforcement agencies’ ability to protect workers and empower them to stand up for themselves. These tools will help protect workers at all wage levels and ensure that even when a worker is subject to a noncompete, they have power to negotiate over the terms of the agreement.

States can ensure that workers know their rights by requiring companies to disclose noncompete requirements in job postings and to provide the terms of proposed noncompete agreements, along with information on the new law, at the time of an initial job offer or the offer of a significant promotion. Early transparency would help workers compare multiple job opportunities; negotiate the terms of the agreement; and potentially challenge the validity of the agreement if they believed it to be illegal. Moreover, early notification reforms would help to ensure that higher-wage workers who are likely to start their own companies do not get trapped in unfair contracts.

For example, Massachusetts’ new noncompete law requires that the proposed contract be provided to workers before a formal offer of employment is made or 10 business days before an employee starts a new job—whichever is greater.94 Oregon law requires corporations to provide notice to workers in a written employment offer two weeks before their first day or upon a “subsequent bona fide advancement.”95 And New Jersey is debating legislation that would require businesses to give workers 30 days to consider such a requirement.96

In addition, state lawmakers should ensure that workers receive financial compensation when their rights are violated and that employers have incentive to come into compliance.

Under existing laws, workers often cannot afford to fight an abusive agreement since the best they can hope for is the revocation or narrowing of the agreement. Moreover, while state attorneys general have been the primary movers of enforcement actions against illegal noncompete and no-poaching agreements, most state attorneys general do not have staff primarily dedicated to labor enforcement.97

In order to ensure that workers can fight for their rights, states must establish significant penalties for violators; designate and fund enforcement agencies—including state and local labor departments—to pursue these sorts of cases; and allow workers to sue companies that violate their rights.

For example, Maine Rep. John Schneck (D) and Sen. Shenna Bellows (D) introduced a bill to strengthen noncompete protections last session. The legislation obligates corporations to disclose the requirement to sign a noncompete contract in job postings and bans them from requiring workers earning less than 300 percent of the federal poverty to sign a contract. In order to make these requirements real, it creates a $5,000 fine for any violations and confers enforcement duties to the state’s Department of Labor.98 In addition, the federal Workforce Mobility Act of 2018 empowers all workers to sue for actual and punitive damages as well as attorney fees.99

Finally, it is important to note that no matter how well-resourced state enforcement agencies are, they cannot do the job alone. To more effectively enforce the law and ensure that workers know their rights, states should partner with trusted worker and community organizations.

While no state or local government has adopted reforms to extend these “co-enforcement” partnerships to noncompete laws, cities and states have adopted these models to improve compliance with other workplace laws. For example, San Francisco and Seattle have implemented community enforcement programs, providing grants to community organizations to help enforce several other types of workplace standards.100 The programs fund recipients to educate workers about their rights; attempt to informally solve disputes directly with employers; and refer victims to the appropriate enforcement agency, guiding workers through the legal process. In addition, California’s Private Attorneys General Act allows workers to sue over labor code violations on behalf of themselves and other workers and to share in the penalties awarded to the state.101

Conclusion

Despite a growing economy and a tight labor market, too many American workers are stuck in jobs they do not want with wages that are too low. A growing body of research shows that noncompete and no-poach agreements are contributing to these negative trends in the American economy by reducing workers’ wages; restricting job mobility; and limiting entrepreneurial and regional economic growth. By taking legislative action to protect workers from abusive noncompete and no-poaching agreements, state policymakers can help to restore workers’ power in the labor market and freedom in the economy.

About the author

Karla Walter is the director of Employment Policy at the Center for American Progress. She focuses primarily on improving the economic security of American workers by increasing workers’ wages and benefits, promoting workplace protections, and advancing workers’ rights at work. Prior to joining CAP, Walter worked at Good Jobs First, providing support to officials, policy research organizations, and grassroots advocacy groups striving to make state and local economic development subsidies more accountable and effective. Previously, she worked as an aide for Wisconsin state Rep. Jennifer Shilling (D). Walter earned a master’s degree in urban planning and policy from the University of Illinois at Chicago and received her bachelor’s degree from the University of Wisconsin-Madison.