The Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, or ATF, is an accident of history. The origins of the modern ATF date back to the Civil War era, when Congress created the Office of Internal Revenue within the Department of the Treasury to collect taxes on spirits and tobacco products. In the decades that followed, ATF slowly acquired jurisdiction over additional areas in a sporadic, piecemeal fashion. Over the years, it has been the accidental repository for federal oversight and enforcement of various industries—alcohol and tobacco in the early 1900s, firearms in the 1930s, and explosives in the 1970s—as the need for such oversight has arisen. ATF slowly evolved from a pure tax collection agency with jurisdiction over one industry into a hybrid regulatory and law enforcement agency charged with the oversight of three of the nation’s most politically fraught consumer products: alcohol, tobacco, and firearms. But over the past 50 years—in the wake of the assassination of a president, his brother, and a civil rights icon and as a crime wave drove gun violence to unprecedented levels—firearms enforcement has become ATF’s primary mission.

Perhaps in part because of the sporadic way in which ATF’s jurisdiction has evolved, the agency has struggled to define a coherent and manageable mission and to implement effective protocols and policies to adequately fulfill that mission, particularly with respect to firearms regulation and enforcement. Asserting itself within the larger framework of federal law enforcement agencies has also posed a challenge for ATF. Periodically, efforts have been made to rebrand the agency or reimagine ATF’s role—including a significant restructuring of the agency as part of the Homeland Security Act of 2002, which moved ATF from the Department of the Treasury to the Department of Justice, or DOJ—but none of these efforts succeeded in addressing all of the challenges facing the agency. These prior attempts to restructure ATF and refine its mission have been undertaken in an atmosphere of intense political scrutiny. After all, ATF is the lead federal agency tackling one of the nation’s most vexing and charged policy concerns: gun violence. And for the past two decades, that already challenging assignment has become even more difficult, as a series of controversies—the siege at Waco, the funding of its new headquarters, its operations at gun shows, and the Fast and Furious gun trafficking operation—have put ATF squarely in the crosshairs of congressional scrutiny and created opportunities for those in the gun lobby determined to debilitate the agency.

An unfortunate legacy of ATF’s evolution is that it suffers from an identity crisis. On the one hand, ATF at times envisions itself as the federal violent-crime police, addressing gun violence through the rubric of broader federal efforts to combat violent gang and drug-related crimes. But ATF was not originally designed to be a police agency and often lacks the internal management and oversight structure required for consistently effective federal law enforcement operations. On the other hand, ATF serves a crucial regulatory function as the sole federal agency responsible for overseeing the lawful commerce in firearms and explosives. Yet the agency has often channeled scarce resources away from the regulatory side of the house and has marginalized the regulatory personnel within the agency. This lack of a clear focus on either enforcement or regulation has prevented ATF from fulfilling any part of its mission quite well enough.

Highlighting the challenges that ATF faces is not just another idle exercise in criticizing the inefficient bureaucracy of the federal government. The problem of gun violence in the United States is urgent: Every day in America, assailants using guns murder 33 people. It is imperative that the federal government takes action to enforce the laws designed to stem the tide of this violence and that it does more to ensure that guns do not end up in the hands of criminals and other dangerous individuals. ATF is the agency charged with that responsibility, and it is well past time for the administration and Congress to take a serious look at ATF and other federal law enforcement agencies to come up with a comprehensive plan to create a strong federal framework to combat gun violence and the illegal trafficking of firearms. While there have been remarkable reductions in violent crime across the country—driven in part by federal law enforcement’s partnerships with local police—illegal gun access continues to contribute to murder rates in the United States that far outpace those in comparable countries. The problem of gun crime in the United States and the daily toll of gun deaths on our communities warrant something new—a large-scale rethinking of how the federal government should address gun violence and illegal firearms trafficking and what ATF’s role should be in that effort.

As reformers in Congress and the administration consider options for how to make ATF function better, it is important to recognize that the agency is composed of dedicated, hardworking agents and civilian staff who do many things very well. In some respects, ATF has been a remarkably successful agency in recent decades. ATF agents as a group are exceptionally productive by traditional measures, especially when compared with agents at other federal law enforcement agencies. In 2013, ATF agents were remarkably productive in the development of cases for prosecution—outperforming Federal Bureau of Investigation, or FBI, agents 3-to-1—averaging 3.4 cases per agent referred to the U.S. Attorneys’ Office for prosecution for every 1 case per FBI agent. ATF agents, more so than most others in federal law enforcement, also have a strong reputation across the country for being assets and effective partners to local law enforcement agencies. ATF agents consistently offer real value and support to local police departments in their efforts to combat local gun crime. Furthermore, ATF has played a role in the overall decline in crime in recent years—the violent crime rate declined 19 percent between 2003 and 2012, and the murder rate declined 17 percent during that period—by taking thousands of violent criminals and gun and drug traffickers off the streets. Between 2005 and 2012, ATF referred more than 13,000 cases involving more than 27,000 defendants suspected of firearms trafficking to the U.S. Attorneys’ Office for prosecution.

Despite these areas of success, ATF has faced some serious challenges in its efforts to be the federal agency charged with enforcing the nation’s gun laws, combating gun crime, and regulating the firearms industry. This report seeks to offer recommendations for how to improve federal enforcement and regulation of guns that recognize and build on the formidable assets that ATF already has—but it does so while recognizing that the status quo is not enough. Although ATF has had many successes, its capabilities are inadequate in relation to the scope of the gun crime challenge in the United States. Therefore, this report does not focus on a series of piecemeal recommendations to improve ATF’s current operations. Prior evaluations, including ones written by authors of this report, make such recommendations; some of them have been acted upon, and others would certainly offer substantial benefits to the functionality and success of the agency. But this report finds that something bigger needs to happen to address the challenges that ATF faces.

What is that something? It begins with a recognition that the United States already has the world’s premiere national law enforcement agency: the FBI. This report concludes that ATF, both its personnel and its mission responsibilities, should be merged into the FBI. The FBI—bolstered by the agents, expertise, and resources of a subsumed ATF—should take over primary jurisdiction of federal firearms enforcement.

In addition to its focus on protecting the nation against terrorism, the FBI has jurisdiction over the enforcement of federal criminal laws and currently operates hundreds of initiatives and operations directed at various types of criminal activity, including violent crime. The FBI is a politically strong and well-respected agency and is therefore able to operate above the fray of politics with adequate funding and resources. The FBI director typically serves a 10-year term across presidencies and through numerous election cycles, which serves to shield the agency’s work from the vicissitudes of elections, partisan politics, and interest group lobbying. And, as is relevant here, the FBI is already deeply involved in federal efforts to combat and prevent gun violence.

This report examines ATF’s existing mission responsibilities and its track record of delivering results. It recommends that Congress and the Obama administration take action to merge ATF and the FBI and make ATF a subordinate division of that agency. This report finds that such action would help address the following three primary challenges that have plagued ATF for years: inadequate management, insufficient resources and burdensome restrictions, and lack of coordination.

Inadequate management

The haphazard way in which ATF has evolved over the years has contributed to fractured leadership at every level. At the highest level, the agency has been passed along from the Department of the Treasury, where it was housed in its current form for 30 years, to DOJ via the Homeland Security Act in 2002. In the more than a decade that ATF has been part of DOJ, it has not been adequately incorporated into the larger family of federal law enforcement agencies, and there has been insufficient oversight of its activities, particularly in the context of developing large-scale operations to address issues of national importance, such as gun trafficking to Mexico.

At the executive level within ATF, the agency has suffered from congressional efforts to keep it without a confirmed director. Prior to August 2013, ATF had been without a full-time, permanent leader for seven years. During that time, ATF was led by a series of acting directors, many of whom worked part time and remotely, while the Senate refused to seriously consider any nominee for director and simultaneously criticized the agency for its lack of leadership. Without a permanent, full-time director, ATF was stuck in limbo, unable to engage in long-term strategic planning and vulnerable to continuous attacks on its competency and effectiveness. While ATF had the benefit of a full-time, confirmed director for 20 months, with former Director B. Todd Jones’ resignation at the end of March 2015, the agency is once again without permanent leadership and likely faces another lengthy period without a confirmed director as the politics of that nomination play out in the same manner as each previous nomination for the position.

There are also extensive management challenges present in other levels of the agency. The leadership vacuum is also apparent on the ground in the field divisions. Over the past 20 years, the agency has developed a culture of limited oversight and lack of accountability that has resulted in a structure of largely autonomous local field divisions that have too little connection to the executive leadership at the agency’s headquarters or to each other. This decentralized structure at times has left room for innovation by the agency’s many talented special agents and, in many offices, has resulted in strong investigative work. But too often, successful strategies in one field division are not transferred to other divisions—and worse, this autonomy has led to a culture of complacency in some field divisions, which has resulted in significant misjudgments and mistakes. Director Jones took important steps to address many of these management challenges, but these problems and the culture that underlies them have developed for decades. It may be beyond the capability of even an exceptionally qualified director to fix some of them.

These weaknesses in leadership throughout ATF have had a significant deleterious effect on morale within the agency. In 2004, ATF ranked 8th out of more than 200 agencies and departments in an annual survey of federal employees about the best offices to work for in the federal government. But by 2014, ATF had dropped to 148th out of 315 agencies and departments overall and ranked 279th out of 314 agencies for “effective leadership” of “senior leaders.” Director Jones himself noted the poor morale among the rank and file when he took over as acting director, describing ATF at that time as an “agency in distress” and saying that “[p]oor morale undermined the efforts of the overwhelming majority of ATF.”

Insufficient resources and burdensome restrictions

ATF’s primary responsibility is enforcing the nation’s gun laws—a responsibility that puts the agency at the center of a political issue that has often been described as the “third rail” of American politics. Particularly in the past two decades, the gun lobby, led by the National Rifle Association, or NRA, has sought to enforce an iron grip over Washington, using both its significant financial resources and its ability to mobilize its members to coerce and cajole Congress into doing its bidding. The NRA has focused its power on three related priorities: enacting laws that loosen or eliminate restrictions on gun owners, crippling ATF with budget restrictions so that it cannot effectively regulate the gun industry and enforce federal firearms laws, and limiting the resources available to ATF to enforce these weak laws under tight policy restrictions.

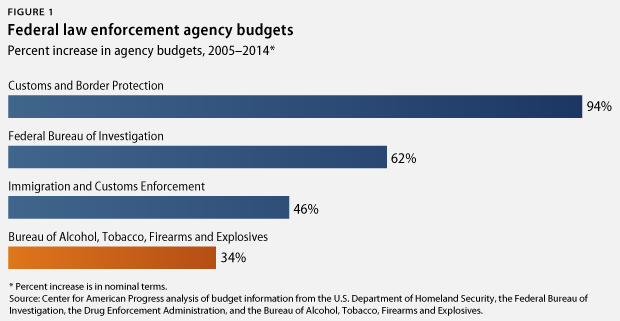

Too often, the gun lobby has succeeded in these efforts. ATF has watched as its budget has slowly stagnated over the past 10 years, even as the budgets of other federal law enforcement agencies have steadily increased. For example, between 2005 and 2014, the FBI’s budget increased 62 percent, Immigration and Customs Enforcement’s budget increased 46 percent, and Customs and Border Protection’s budget increased 94 percent. In contrast, the budget for ATF increased from around $878 million in 2005 to only $1.18 billion in 2014, a modest increase of around 34 percent that, when adjusted for inflation, amounts to only a 10 percent increase.

This budget environment means that ATF is significantly underresourced, both compared with other law enforcement agencies and with its own staffing levels of a few years ago. In 2014, ATF employed 2,490 special agents—only 173 more agents than the agency employed in 2001. The number of ATF agents currently in the field nationwide investigating gun crime and illegal firearm trafficking is less than the individual police forces of Dallas, Texas; Washington, D.C.; and many other major metropolitan police departments, making it nearly impossible for these agents to adequately address gun crime across the country. The regulatory side of the house is in even more dire shape. In 2014, ATF employed only 780 investigators to regulate the nation’s firearms manufacturers, importers, and dealers, as well as the explosives industry. That is 18.8 percent fewer investigators than the agency employed in 2001, yet the size of the industry they are charged with regulating grew substantially during the same period.

In addition to these budget shortfalls, ATF is also hamstrung by a series of riders to annual appropriations legislation that have hobbled the agency and limited its ability to fulfill even the most basic parts of its mission. These riders, which number more than a dozen, have been tacked onto appropriations legislation at the behest of the gun lobby and impose severe restrictions on ATF’s activities, including limitations on ATF’s ability to manage its data in a modern and efficient manner, measures that interfere with the disclosure and use of data critical to law enforcement and public health research, and prohibitions on activities to regulate and oversee firearms dealers. Merging ATF into the FBI would have the immediate effect of voiding these dangerous and unnecessary budget restrictions—and, more broadly, the merger would help insulate the mission of enforcing federal gun laws from political interference while helping provide a new infusion of resources.

Lack of coordination

Gun crime presents an exceedingly complicated challenge. There are an estimated 300 million guns in private hands in the United States, and gun ownership is a strong tradition in our country’s history that is protected by the Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. While America experiences violent crime rates similar to other comparable nations, it has extraordinarily high rates of murder and gun crimes. Effectively combating this gun crime and preventing future gun violence is further complicated by the facts that gun laws vary widely across states and gun violence is often intertwined with other criminal activity, such as gang violence and illegal drug trafficking. In order to be effective, therefore, ATF must be able to coordinate with local law enforcement agencies to identify the individuals responsible for gun violence in a community, apprehend such individuals, and obtain information from them regarding from where the illegal guns are coming.

By and large, ATF is quite effective at this type of coordination. However, a significant portion of gun-related crime has an interstate element. For example, in 2009, 30 percent of guns that were recovered from crimes and could be traced had originally been purchased in another state. For this reason, there must also be a strong federal law enforcement agency to take the lead on investigating this type of multijurisdictional criminal problem. In recent years, ATF has made an effort to position itself as this agency, asserting that it is the primary federal law enforcement agency addressing violent crime, including gun crime, in communities around the country.

Efforts to paint ATF as the federal violent-crime police put it in tension with the mission of the FBI, which is in part “to uphold and enforce the criminal laws of the United States.” This conflict is more than just semantic. There exists considerable overlap between the work and resources of ATF and the FBI in the areas of guns, explosives, and violent crime. For example, the FBI has a well-established anti-gang initiative that targets violent street gangs across the country. But ATF has also targeted violent gangs for investigation because of their use of guns in crimes and often works with local law enforcement to bring gang-related cases to federal court. The FBI operates the National Instant Criminal Background Check System used for gun sales by federally licensed dealers, but ATF operates the regulatory system that issues those licenses and the database for tracing crime guns. Both agencies have extensive training programs for explosives forensics and investigations, and both agencies operate numerous forensic laboratories that process evidence from violent crime scenes. Both agencies have specially trained response teams to handle emergencies such as hostage-taking, serious explosive-related incidents, and large-scale special events such as the Super Bowl.

Despite the significant overlap in the mission, resources, and expertise of these two agencies with respect to firearms enforcement, explosives, and violent crime, ATF and the FBI have been unable to consistently and effectively collaborate to define a singular plan for combating gun violence and illegal gun trafficking in the United States—or such a plan around explosives investigations. Many attempts to improve coordination have been made by the leaders of both agencies, and all have failed to truly solve the problem. Indeed, the relationship between the two agencies has often been characterized more by competition over cases and turf battles than by collaboration and cooperation. Finding a way to foster such collaboration would have two significant benefits. First, combining the assets of these two agencies would reduce overlap and waste and would provide some cost savings at a time when all government agencies are struggling to maintain budgets. And merging the expertise of these two agencies would result in more effective and successful enforcement of federal firearms and explosives laws and a better approach to combat violent crime.

Recommendations

The proposal to merge ATF into the FBI is not a reactionary proposal aimed at “fixing” ATF based on its most recent political or organizational challenges. Rather, this proposal is offered in an attempt to define a fresh vision of how the federal government could best address the issue of gun violence in this country. If we were to start from scratch, how would we structure federal law enforcement to most effectively enforce criminal gun laws and regulate the gun industry? We would almost certainly create one central law enforcement agency charged with that mission and would ensure that this agency had adequate resources and the political support necessary to succeed. We would take steps to minimize agency overlap and jurisdictional confusion and would position that one federal agency to enhance the work of local law enforcement to combat violent crime and ensure that guns do not end up in the hands of dangerous people. And we would structure that agency to provide strong leadership, management, oversight, and accountability to ensure that its enforcement activities were successful. Merging ATF into the FBI is a way of creating this kind of agency. This merger would also enhance ATF’s other mission areas, particularly explosives, arson, and emergency response.

The recommendations made in this report are the result of an 18-month investigation into ATF: what is working, what is lacking, and what the agency would need to be truly successful. The information contained herein comes from an extensive review of publicly available information about ATF and the FBI, as well as interviews with more than 50 current and former employees of both agencies and those who supported or supervised ATF and the FBI at the Justice and Treasury departments. The authors also spoke with congressional staff charged with overseeing ATF, local law enforcement officials, researchers who have studied gun crime, and other persons whose knowledge and experience might offer insight. In many cases that involve current and former agents and employees of ATF, the FBI, and the Justice Department, information is presented here anonymously to protect the confidentiality of sources—particularly those who continue to work for the federal government and were thus not authorized to speak to the authors.

In the pages that follow, we provide a detailed examination of ATF and other aspects of federal firearms enforcement that includes:

- A brief history of ATF to place its current challenges in context

- A description of the key mission activities that the agency currently undertakes

- A discussion of the three key challenges facing the agency—leadership, resources and restrictions, and coordination—in the context of those mission activities

We then offer one core recommendation for changing the way the federal government approaches firearms enforcement and regulation to better protect public safety and reduce gun violence: merging ATF into the FBI.

We do not make the core recommendation of this report lightly and recognize that operationalizing this type of agency restructuring would be challenging and time consuming. History has shown that large-scale reorganizations of wide swaths of the federal government often look much better on paper than in practice. Certainly, there would be resistance and apprehension by members of each agency, both of which would be wary of the challenges presented by such a reorganization. And there is a risk that a poorly executed merger would create more problems than it would solve. But the problem of gun violence in the United States warrants this kind of large-scale rethinking of how federal law enforcement can better address this issue. In the view of the authors, the potential benefits outweigh the potential risks. The gun violence challenge is simply too important to be satisfied with the status quo, and it warrants big thinking and creative solutions. In this report, we strive to offer one such solution.

Chelsea Parsons is Vice President of Guns and Crime Policy at the Center for American Progress. Arkadi Gerney is a Senior Vice President at the Center. Mark D. Jones is a former supervisory special agent with the U.S. Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives. Elaine C. Kamarck is a senior fellow in the Governance Studies program at the Brookings Institution and the director of the Management and Leadership Initiative at Brookings.