Two years later, however, business investment is actually declining. Factory closings and mass layoffs have not ended. Wage growth is tepid, despite the continuation of the economic expansion that began 10 years ago, and gross domestic product (GDP) growth is slowing and projected to revert to its long-term trend or below. Meanwhile, budget deficits are higher due to revenue losses—which have largely been triggered by the massive corporate tax cut at the heart of the TCJA. Nevertheless, earlier this month, acting White House Chief of Staff Mick Mulvaney told a gathering of CEOs that the Trump administration will seek to cut the corporate tax rate further if the president gains a second term in office.

This column explores just how much the bill has benefited corporations in the two years since its passage.

The TCJA gave corporations an even bigger tax cut than originally projected

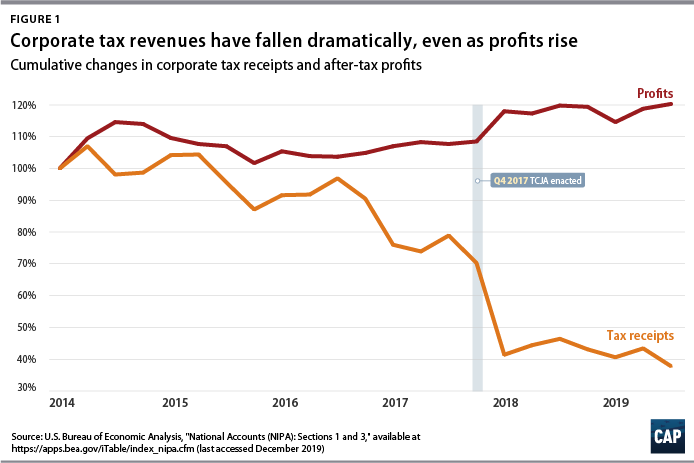

Since the TCJA was enacted, corporate tax revenue has been down from its projected level by about one-third, even as pretax corporate profits have continued to rise toward historic highs. (see Figure 1) The main reason for the drop in corporate tax revenue is obvious: The TCJA slashed the corporate rate by 40 percent, from 35 percent to 21 percent. But the falloff in corporate revenue has been even sharper than expected.

Several months before the TCJA was enacted, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected that corporate tax revenues for fiscal years 2018 and 2019 would total $668 billion. In the forecast published soon after the TCJA was enacted, however, the CBO projected $519 billion in corporate tax revenue over those two years—a $149 billion decrease. Actual corporate tax revenue over that period came in significantly lower, at $435 billion—a $233 billion drop. Essentially, corporations have already received $233 billion in tax cuts, $84 billion more than the CBO projected. To put that in perspective, the federal government spent just $47 billion on Pell Grants over the past two years.

The CBO’s adjusted forecasts now put the 10-year cost of corporate tax cuts at roughly $750 billion, $400 billion more than the pre-TCJA projections. That figure includes the temporary revenue from the TCJA’s repatriation provision, which gave corporations steeply discounted tax rates on stockpiles of overseas profits from prior years.

The cost of the corporate tax cut could also swell in the coming years because of the way it was designed. To limit the official cost of the bill, the TCJA’s authors included various provisions to raise corporate tax revenue, partially offsetting the revenue loss from the reduction in the corporate tax rate. For example, the TCJA imposed certain new limits on the deductions that corporations can take for interest expense; the law requires corporations to amortize, or spread out, their research expense deductions over five years, and it implemented a new minimum tax on overseas profits. But these provisions are not fully in effect until 2022 or later. Undoubtedly, corporations that lobbied for the TCJA’s passage will again turn to Congress requesting relief from these delayed revenue-raising provisions.

Similarly, the TCJA includes special tax breaks for corporations that are only temporary, including immediate write-offs for equipment and machinery investments, which companies will likely seek to extend. If Congress complies—which is possible or even likely, if past experience is any indication—then the cost of the TCJA’s corporate tax cuts will increase by hundreds of billions of dollars.*

Many large, profitable corporations are paying no tax

Researchers at the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) surveyed corporate financial reports for the first year that the TCJA was in effect and recently published their findings. Examining 379 profitable Fortune 500 companies, they found that the companies paid an average effective tax rate of just 11.3 percent on their U.S. income in 2018—slightly more than half of the 21.2 percent average effective rate that large corporations paid from 2008 to 2015. Shockingly, ITEP found that 91, or nearly one-quarter, of these major corporations paid no federal income tax on their U.S. income in 2018.

The TCJA tax cuts aren’t working

One of the core arguments for the TCJA’s dramatic corporate tax cuts claimed that the tax cuts would spur a boom in investments that would increase worker productivity, such as new factories or equipment. These investments would then increase economic output, and workers would be able to capture the benefit by bargaining for higher wages. But the first link in this flawed chain of reasoning has already broken. Businesses have not massively increased investment; in fact, growth in nonresidential fixed investment has been on a downward trend since the beginning of 2018, just after the TCJA’s passage. Part of this decrease in business investment is likely due to President Trump’s ill-considered tariff policies. But experts warned of this outcome even before the enactment of the TCJA, emphasizing that corporate access to capital was in no short supply: In 2017, interest rates had been low for a decade; after-tax profits were already near all-time highs; and corporations had record amounts of cash on hand. There was no real indication that corporations faced serious liquidity constraints that prohibited them from making investments to begin with, or that changes in the corporate tax rate would have a major impact on investment.

Yet, as critics also warned, the TCJA did not lead to these types of investments. Upon the bill’s passage, corporations began funneling their extra tax windfall to shareholders instead. A recent analysis from the International Monetary Fund found that the top S&P 500 companies directed just 20 percent of their increased cashflow toward capital expenditures or research and development, while putting the other 80 percent toward buybacks, dividends, and other asset planning adjustments. These types of expenditures overwhelmingly benefit foreign investors and the wealthy, who own the majority of corporate stocks.

The long-term trickle-down effects that proponents of corporate tax cuts predicted can only be borne out if corporations dramatically boost necessary investments—and even then, the benefits for workers are uncertain because workers would only realize them to the extent they were successful in bargaining for their share of the gains.

The tax cuts have not led to increased economic competitiveness

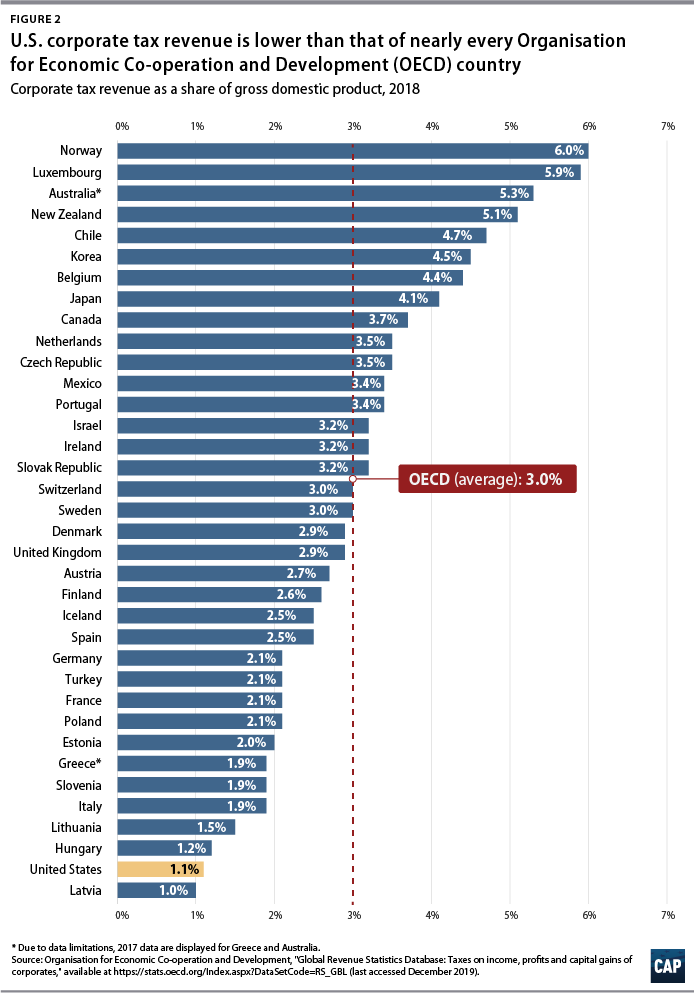

Another core argument of TCJA proponents was that the law’s tax cuts would help improve economic competitiveness. Requiring U.S. corporations to pay less tax on their profits would give them a leg up over firms in other countries with higher tax rates. Even before the TCJA, however, effective corporate tax rates were in line with major trading partners, and the United States raised less revenue from corporate taxes than most other peer countries. In 2017, only four countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) raised revenue from corporations as a share of GDP at a lower rate than the United States; by 2018, there was only one. Because of the TCJA, the United States now collects only 1 percent of GDP in corporate tax revenue—just one-third of the OECD average and far less than neighbors Canada and Mexico, which collect 3.7 percent and 3.4 percent, respectively. (see Figure 2) Part of the reason the United States ranks so low is that a larger share of business income is earned by noncorporate businesses that are not subject to any corporate tax; their profits pass through to their owners, who pay tax on that income as individuals. So-called pass-through business income also received large tax cuts in the TCJA.

Conclusion

It has been two full years since Congress passed the TCJA, and it is increasingly clear that the bill will not live up to its proponents’ exaggerated promises. Indeed, the tax cut has accomplished much less and cost much more than its proponents promised.

Based on previously debunked economic theory, the bill will reduce revenues by trillions of dollars over the decade. So far, the large corporate tax windfalls have gone mostly toward lining the pockets of already wealthy individuals, and there is little evidence that middle- and working-class families will see real benefits. At this point, the last thing the U.S. economy needs is more corporate tax cuts such as those that White House Chief of Staff Mulvaney suggested. Congress should work to reverse this trend of costly and ineffective cuts to corporations and put in place legislation that raises revenues in a progressive way.

* Authors’ note: The Joint Committee on Taxation estimated that amortization of research expenses would raise $120 billion in revenue from corporations and other businesses over 10 years. According to the CBO, extending full “expensing” would reduce tax revenue by $179 billion over the next decade. Estimates are not available for the other delayed revenue-raising provisions, but they are known to be significant, as the underlying provisions are major pieces of the TCJA that substantially change important parameters. Along similar lines, another tax break in the TCJA is scheduled to become less generous for corporations beginning in 2026: the deduction for foreign-derived intangible income.